Although secondary intention healing (SIH) is a fundamental aspect of postoperative care following Mohs micrographic ssurgery (MMS), it is currently underutilized. SIH constitutes a safe, cost-effective, and versatile method for wound closure. SIH offers multiple advantages, including enhanced cancer surveillance, reduced pain, and promosing esthetic outcomes, particularly not only on certain anatomical regions such as the medial canthus, antihelix, temple, or alar crease, but also for relatively small and superficial defects on the eyelids, ears, lips, and nose, including the alar region, and defects on the hands dorsal regions. Careful patient selection and thorough risk assessment are imperative to mitigate potential complications, including retraction, hyper/hypopigmented scars, or delayed healing. This comprehensive review aims to inform evidence-based decision-making on the role of SIH in MMS, synthesizing its indications, advantages, complications, wound care, and integration with other reconstructive methods.

La curación por segunda intención (CSI) es un aspecto fundamental de la Cirugía Micrográfica de Mohs (CMM), pese estar actualmente infrautilizada. CSI representa un método seguro, rentable y versátil para el cierre tras CMM. CSI tiene múltiples ventajas: mejor vigilancia de recurrencia cancerígena, reducción del dolor y resultados cosméticos favorables, particularmente en determinadas regiones anatómicas como el canto medial, antihélix, sien o pliegue alar nasal, pero también para defectos relativamente pequeños y superficiales en párpados, orejas, labios, nariz y dorso de manos. Una selección cuidadosa de los pacientes es esencial para limitar potenciales complicaciones (retracción, cicatrices hiper/hipopigmentadas o retrasos en la cicatrización. Esta revisión tiene como objetivo proveer la toma de decisiones basada en evidencia en el manejo con CSI de defectos post-CMM sintetizando sus indicaciones, ventajas, complicaciones, cuidado de heridas e integración con otros métodos reconstructivos.

Originally, Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) predominantly was used a fixed tissue technique, while defects were left to heal by secondary healing intention (SIH).1–4 The appearance of this fresh tissue technique in the 1960–70s led to a shift toward more sophisticated methods for wound closure, with SIH currently accounting for <25% (0.8–37.9%) of cases reported.1–4 The seminal work by Zitelli from 1983 introduced SIH as a straightforward wound management technique which was particularly praised for its excellent esthetic outcomes on certain facial sites5. SIH offers enhanced cancer monitoring, simplified wound care, and low-rate of complications.6,7 Recent literature has reported expanded applications of post-MMS SIH in anatomical areas previously deemed suboptimal.1–3 This review aims to provide an update on SIH indications and advantages, focusing on anatomical considerations.

MethodsWe performed a comprehensive narrative search of the literature across PubMed and Google Scholar, from inception to April 2024 using the following key words: “Mohs”; “Mohs Surgery”; “Secondary intention healing”; “Secondary intention”. Articles with a Spanish, English or German version were included and selected according to their relevance.

A potential limitation of this review is that the choice of SIH is not significantly impacted by whether the defect is due to MMS or conventional surgery. Limiting the search to MMS may have overlooked relevant SIH data from other surgical techniques, which is acknowledged in the findings interpretation.

Indications for secondary intention healingThere are certain cases in which SIH should particularly be considered1,5,8,9:

- 1.

Tumors in high-risk areas where a delayed closure is considered, especially in concave areas.

- 2.

Tumors with aggressive features or when MMS is especially complex: post-MMS relapses or >3 MMS Stages.

SIH could also be suitable for patients with certain comorbidities including coagulation disorders, advanced age, and social or work conditions that contraindicate complex surgery.

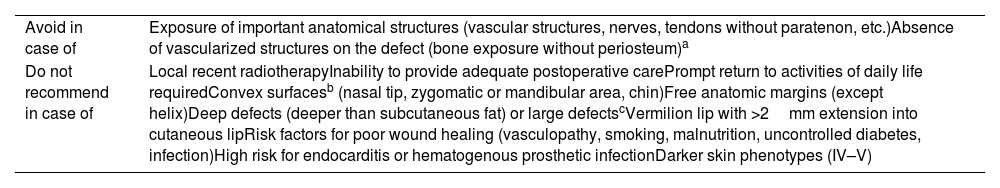

ContraindicationsThe main contraindication for SIH is exposure of sensitive anatomical structures, such as vessels or nerves9. Special caution should be taken in cases of previous or concomitant radiotherapy9,10 (higher risk of prolonged reepithelization and radionecrosis, and SIH time-to-epithelize can interfere with optimal radiotherapy schedule), inadequate postoperative care; predicted poor functional outcomes; or patients with social or occupational obligations requiring prompt reinstatement1,9,10 (Table 1).

Precautions on the use of SIH post-MMS.

| Avoid in case of | Exposure of important anatomical structures (vascular structures, nerves, tendons without paratenon, etc.)Absence of vascularized structures on the defect (bone exposure without periosteum)a |

| Do not recommend in case of | Local recent radiotherapyInability to provide adequate postoperative carePrompt return to activities of daily life requiredConvex surfacesb (nasal tip, zygomatic or mandibular area, chin)Free anatomic margins (except helix)Deep defects (deeper than subcutaneous fat) or large defectscVermilion lip with >2mm extension into cutaneous lipRisk factors for poor wound healing (vasculopathy, smoking, malnutrition, uncontrolled diabetes, infection)High risk for endocarditis or hematogenous prosthetic infectionDarker skin phenotypes (IV–V) |

SIH can be used on exposed bone or cartilage as long as there is blood supply. This can be achieved by punching holes in the cartilage or burring holes in the bone.

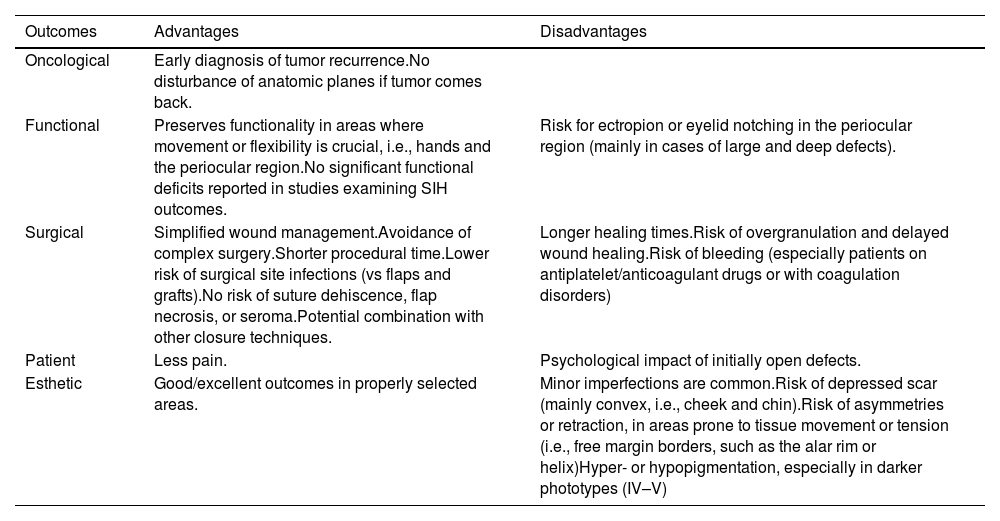

The main advantage of SIH is the efficient detection of tumor recurrence (Table 2). Furthermore, there is no risk of certain adverse effects (seroma, suture granuloma, secondary suture failure), a lower risk of surgical site infection (SSI), and hematoma.1,11,12

Advantages and disadvantages of SIH in MMS.

| Outcomes | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Oncological | Early diagnosis of tumor recurrence.No disturbance of anatomic planes if tumor comes back. | |

| Functional | Preserves functionality in areas where movement or flexibility is crucial, i.e., hands and the periocular region.No significant functional deficits reported in studies examining SIH outcomes. | Risk for ectropion or eyelid notching in the periocular region (mainly in cases of large and deep defects). |

| Surgical | Simplified wound management.Avoidance of complex surgery.Shorter procedural time.Lower risk of surgical site infections (vs flaps and grafts).No risk of suture dehiscence, flap necrosis, or seroma.Potential combination with other closure techniques. | Longer healing times.Risk of overgranulation and delayed wound healing.Risk of bleeding (especially patients on antiplatelet/anticoagulant drugs or with coagulation disorders) |

| Patient | Less pain. | Psychological impact of initially open defects. |

| Esthetic | Good/excellent outcomes in properly selected areas. | Minor imperfections are common.Risk of depressed scar (mainly convex, i.e., cheek and chin).Risk of asymmetries or retraction, in areas prone to tissue movement or tension (i.e., free margin borders, such as the alar rim or helix)Hyper- or hypopigmentation, especially in darker phototypes (IV–V) |

Drawbacks include prolonged healing time (increased with compromised healing process, e.g. prior radiotherapy, diabetes and mTOR inhibitors therapy), increased risk of bleeding (especially in patients on antiplatelet/anticoagulant therapy or with coagulation disorders), and risk of retraction or poor esthetic outcomes, especially if free anatomical margins are involved.

CosmesisIn an appropriate surgical context, SIH can result in similar or better esthetic outcomes vs surgical closure.12,13 The most important factor is the contour of the areas involved: more favorable results on concave profiles (Fig. 1). Secondary factors are wound size and depth (better if small and superficial), patient age, and skin color. SIH tends to leave hypopigmented scars, which are less visible in lighter skin phenotypes.2,3,14,15

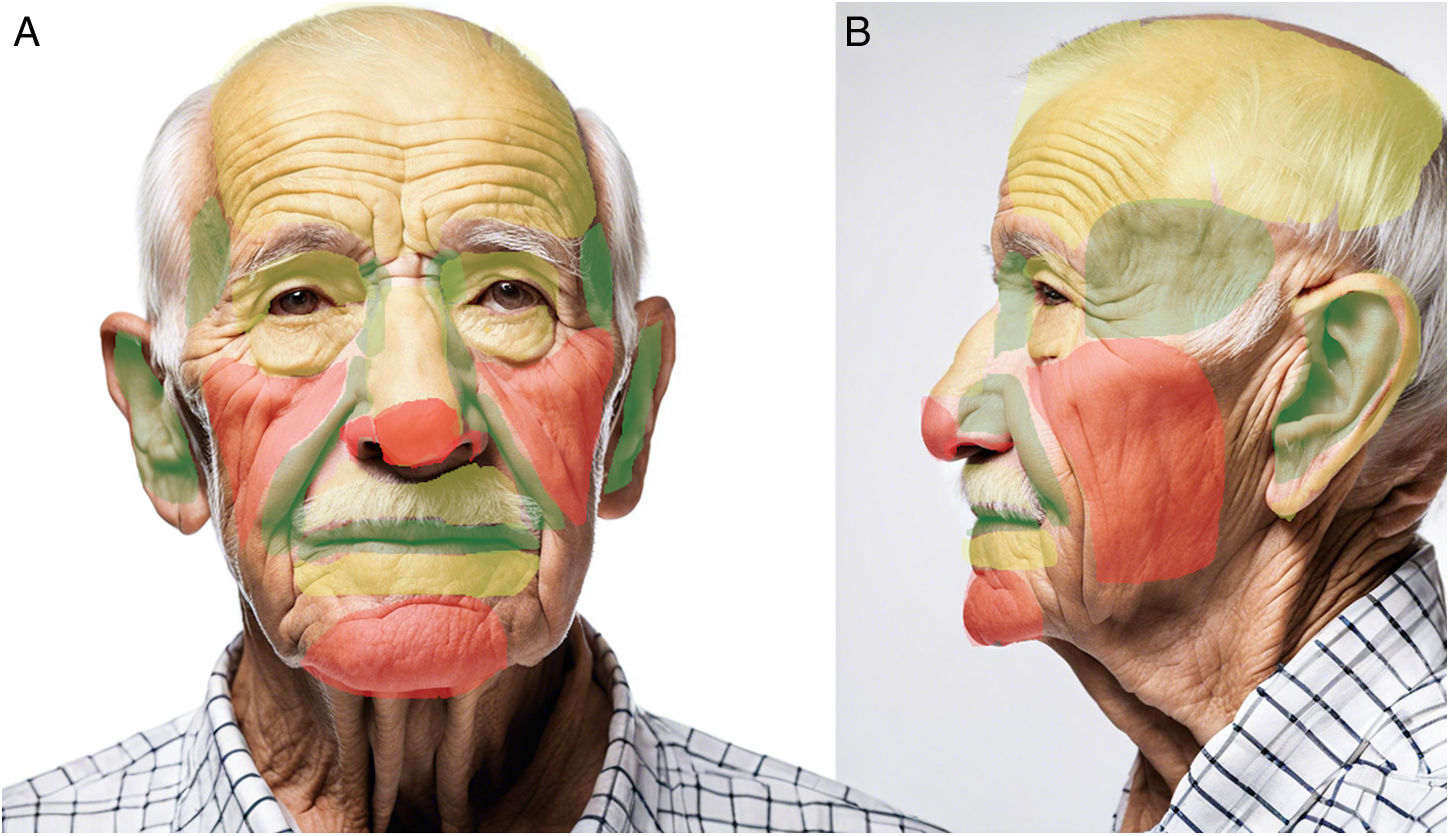

Facial concavities (medial canthus and conchal bowl) heal imperceptibly, whereas convex surfaces (nasal tip and malar cheek) can heal poorly with depressed scars. Although flat areas of the cheeks, forehead, and chin heal properly, cosmesis can be unpredictable. These regions were summarized by Zitelli5 as NEET (concavities of the nose, eyes, ears, and temple), NOCH (convexities of the nose, oral lips, cheek, chin, and helix), and FAIR (flat areas of the forehead, antihelix of the ear, eyelids, and rest of the nose, lips, and cheeks). However, indications for SIH have since expanded to other anatomical regions2,6,8 (Fig. 2).

Map of esthetic outcomes of SIH depending on anatomical regiona. Green=good outcomes; Yellow=good outcomes in selected cases; Red=poor outcomes except for superficial and small wounds. aFront- and side-view images were generated using DALL-E by OpenAI and then modified to indicate different colored areas.

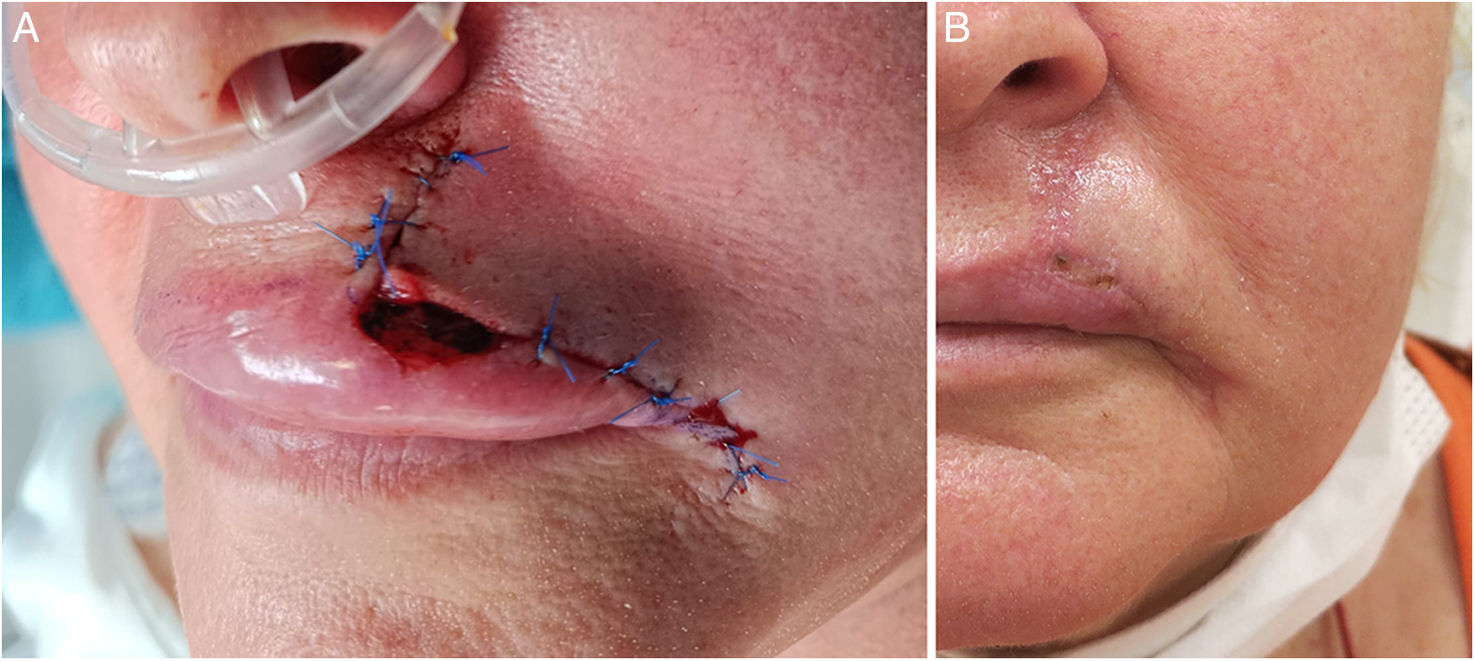

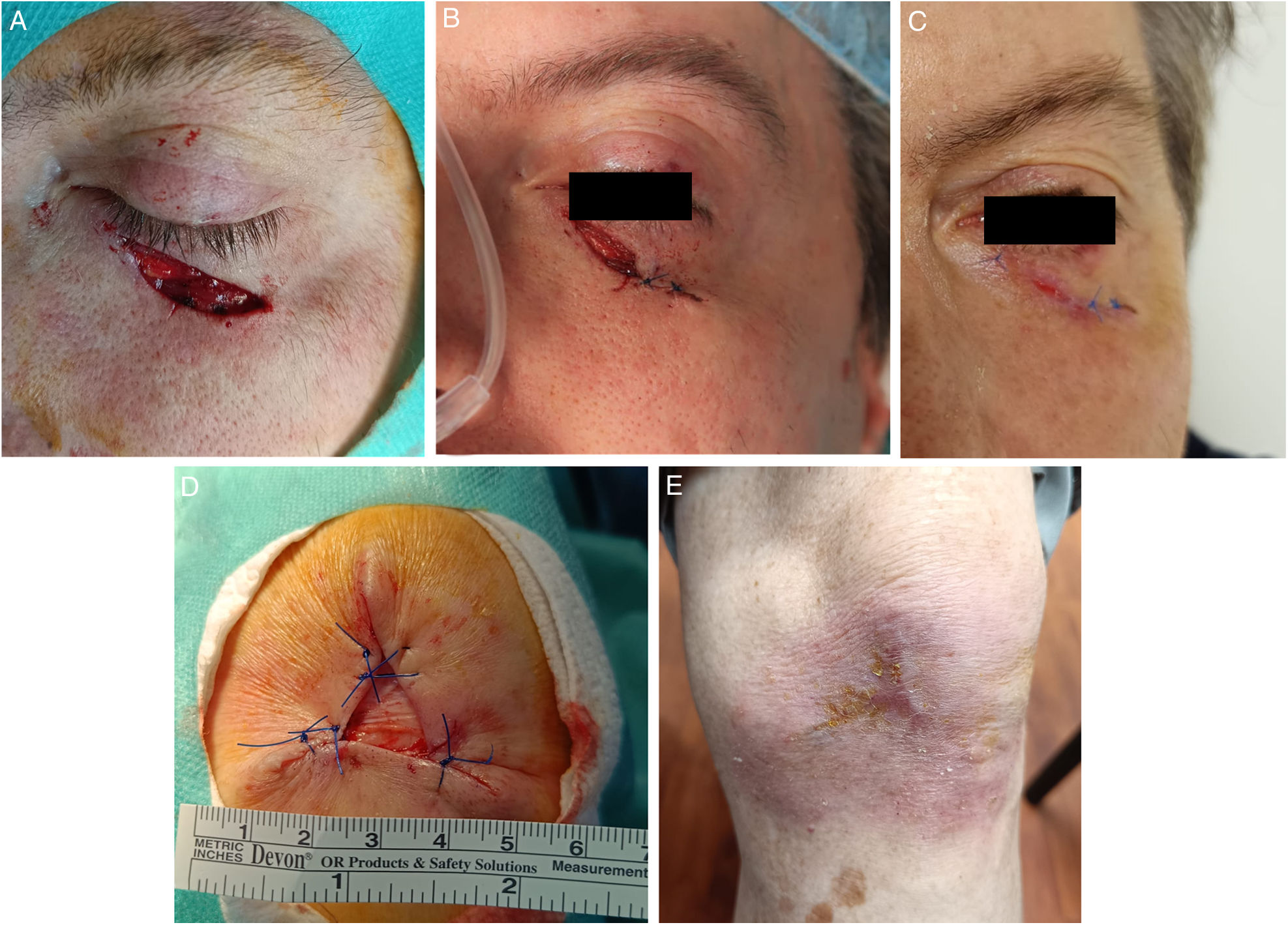

SIH can be combined with various repairing techniques, offering versatility in wound closure, i.e. wounds affecting≥2 cosmetic subunits (Fig. 3). Combination with purse string or partial closures can minimize the area requiring SIH (Fig. 4), thus reducing healing time14. In situations of uncertainty, SIH can be employed, and esthetic outcomes later be evaluated. This approach reveals new options as the wound becomes smaller and more vascularized14.

(A–C) Partial closure together with SIH. Lower eyelid defect (2.5mm×0.7mm) after MMS (A). Direct closure on the lower-lateral region, SIH on the upper-medial region (1cm×0.6cm) (B). Almost complete re-epithelization 10 days later. No ectropion was reported (C). (D–E) Defect on the left knee (3.5cm×3cm) of a 94-year-old man. Partial closure of the defect. SIH of the central region (1.5cm×1.5cm) (D). Complete re-epithelization 40 days later. Excellent functional outcomes (E).

The rates of postoperative complications with SIH are low (<3%), and probably less common than with other closure techniques.1,2,16 SIH is associated with a comparatively lower risk of complications such as hematoma1, patients exhibit less postoperative pain17, and SSI happen to be a rare finding (0.7% up to 4.2%)18–22.

Failure to re-epithelize may be due to various factors (epidermal maturation arrest, persistent granulation tissue, deficient blood supply, or infection) and wound contraction can lead to retraction and unfavorable cosmesis, particularly at free anatomical borders, i.e., ectropion in the palpebral region. Other rarer potential complications include eyelid notching/webbing, trichiasis, telangiectasia, hemorrhage, bone necrosis, osteomyelitis, depressed scars, and hyperplastic granulation1.

Antibiotic prophylaxis and topical antibioticsCurrent clinical practice guidelines specify that pre- or perioperative antibiotics should be prescribed to patients who are susceptible to endocarditis and prosthetic joint infection after surgical procedures in contaminated areas, such as the oral mucosa, infected non-oral sites, or high-risk of local infection23. A recent meta-analysis showed no statistically significant reduction in SSI in MMS after oral antibiotic prophylaxis vs placebo24. Specifically in SIH, in a randomized clinical trial with 84 patients undergoing SIH on the auricular regions, no difference in SSI was seen in patients with or without levofloxacin prophylaxis (2.4% vs 2.5%)25. According to the 2023 position paper of the German Society of Dermatology, there is insufficient evidence to support perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis and/or the topical application of antibiotics on wounds undergoing SIH. Routine application of antibiotic-containing ointments should be avoided to prevent sensitization, in the absence of skin barrier, and antibiotic resistance.26,27

Wound careBasic wound care can be administered by the patient, a family member, or a nurse, with scheduled visits to the dermatologist for follow-up. The wound should be kept clean to be able to apply an occlusive ointment (petrolatum or similar)2,9,28 and a conventional or hydrocolloid dressing. Dressing change frequency—every 2–7 days—depends on the amount of secretion leakage, and patients should be made aware of SSI signs.2,9 However, the management of wound care should be individualized based on specific factors including patient age, comorbidities (i.e., diabetes, peripheral vascular disease), and location and size of the defect.

Secondary intention healing after Mohs micrographic surgery on specific anatomical areasEarSIH for auricular defects after MMS has been used extensively29 with good esthetic and functional outcomes. In a study on 133 patients with full-thickness auricular defects (helix, antihelix, concha, pretragal, tragal area, lobule, and posterior aspect), SIH had excellent esthetic outcomes, particularly in concave areas, even if the cartilage was removed (except for the helix, where a depression persisted). Minor cartilage exposure (<1cm) was not a contraindication. All wounds healed in less than 10 weeks.29 In a recent systematic review of the reconstruction of the auricular concha, SIH was considered a valid option although with a higher risk of SSI30. In a recent study, SIH yielded esthetic outcomes similar to full-thickness skin grafts on the helix (mean diameter, 1.7cm up to 1.9cm), without any differences being reported in adverse events31. Even if there is a higher risk of depressed scars, many patients, especially the elderly, consider slight depressions cosmetically acceptable.31. Recent comparative studies have shown that while split-thickness skin grafts may lead to faster healing, SIH patients experienced significantly less pain32.

NoseA retrospective study including 96 defects on the nose (nasal tip, n=39; alar region, n=32; sidewall, n=17, and dorsum, n=8), with a mean size of 0.83cm2, revealed that diameter and depth significantly impacted scar outcome (p<0.001). Nasal defects <1cm and, which did not extend beyond the superficial fat healed well with SIH regardless of their location33. A former study with 37 patients showed better results on concave areas—nasal ala and sidewall—and worse on the nasal tip (except if small and superficial)12 (Fig. 5). Regarding mean healing time, a retrospective study reported 3–4 weeks for alar or nasal tip defects of 0.5cm up to 1.5cm in size34.

SIH on folds. (A–C) Lentigo maligna on the nasolabial fold. (A) Delimitation of lentigo maligna prior to MMS. The nasolabial fold defect (3cm×4cm) was closed using a plication of the upper and lower borders. The central defect (2cm×0.6cm) was left to SIH (B). Complete re-epithelization 4 weeks later (C). (D–E) Defect on the alar groove. Defect (1.5cm×0.5cm) after MMS. (B) Almost complete re-epithelization 3 weeks later. No retraction of the nasal ala seen at the follow-up.

Regarding the nasal ala, in patients unable or unwilling to undergo complex nasal flaps, free-cartilage batten graft (FCBG) along with SIH can be a useful alternative.35,36 In a retrospective study of 129 patients who underwent FCBG with SIH good to excellent results were obtained, especially in superficial or small to intermediate-sized defects, with the cartilage closely approximating defect size, as shown in former studies37,38. Healing time was estimated from 6 (small/superficial defects) up to 9 weeks (deeper/larger wounds). Only 14% of patients presented alar retraction. No hematomas or infections were reported35. The authors concluded that FCBG with SIH may be considered in mid-alar wounds that are relatively shallow—>4mm from the alar rim—and filled with a cartilage graft that is 75% up to 100% of the defect size.39,40

The nasal tip does not universally heal well after SIH due to the risk of asymmetries and atrophic scars, and most surgeons prefer other surgical procedures41. SIH in the alar rim should be used with caution, especially where there are large or deep defects, since there is a risk of retraction, poor cosmesis, and collapse.5,42

LipsClassically, SIH was considered in vermilion-only and partial-thickness defects (superficial involvement of the orbicularis muscle).43,44 In a study with 68 cases of vermilion defects (mean size, 1.2cm2) patients achieved excellent functional outcomes with good cosmesis (87% of patients would choose SIH again)11, even for vermilion defects as large as 2.8cm2, or involving cutaneous lips (22/68) and/or muscular layers (23/68). A similar study with 25 patients with intermediate and large partial thickness defects (mean size, 1.6cm), showed good to excellent esthetic and functional outcomes44. Smaller case series revealed similar results44-46. Reported mean healing time for intermediate/large partial thickness defects on the lips was 25 days44. SIH of the vermilion can also be combined with lateral advancement flaps if the defect involves>2mm of cutaneous lip.45,46 Defects extending deeper than the superficial orbicularis muscle may result in esthetic or functional deformities46 and other surgical techniques should be considered alone or in combination with SIH45.

Regarding the upper lip—with no involvement of the vermillion—a study with 105 patients with lip and chin defects showed satisfactory healing for the alar base and upper lip13. The apical triangle is the superior tip of the upper lip, bound by the medial cheek, nasal ala, and a hypothetical border extending from the nasolabial fold. A retrospective study (n=24) confirmed good esthetic outcomes with SIH, with no statistically significant differences vs immediate closure47.

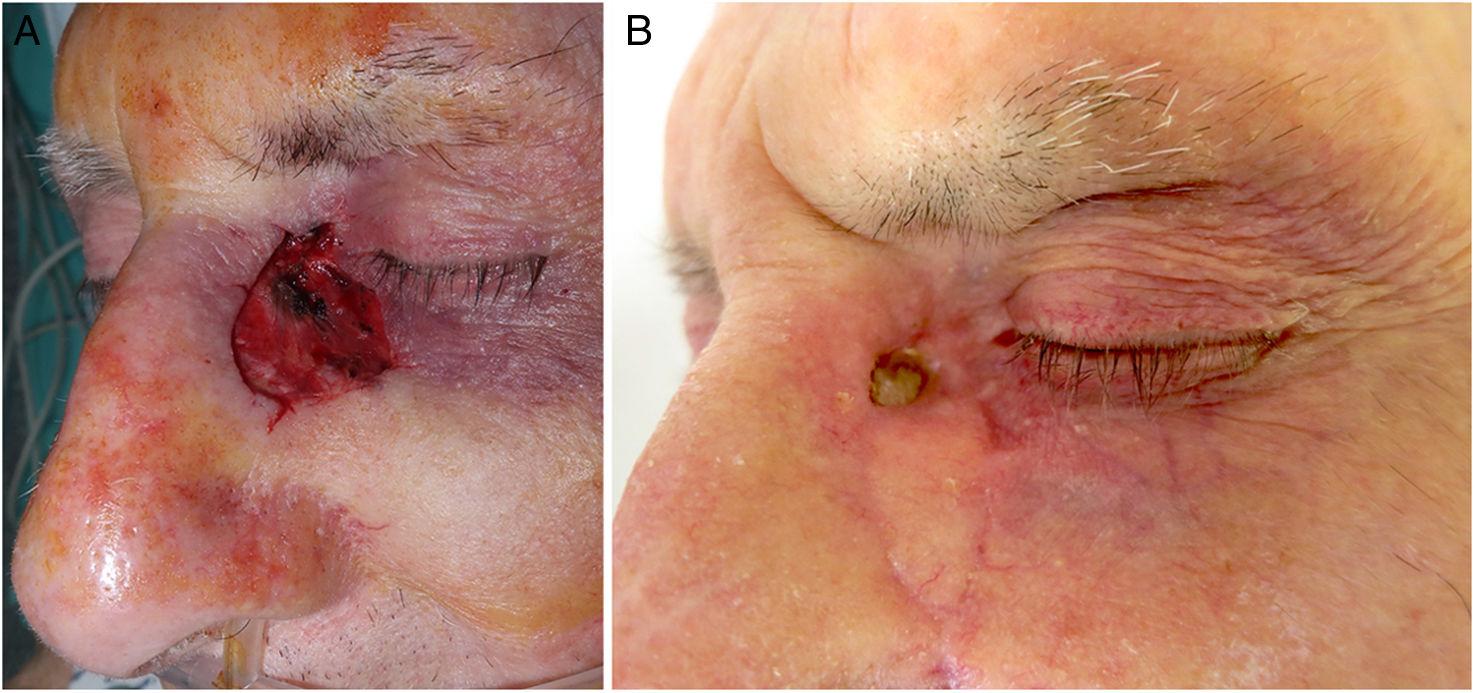

Periocular regionSIH has traditionally been used for small and concave wounds, such as on the medial canthus48. However, a retrospective study on 39 periocular wounds: lower eyelid, n=14; upper eyelid, n=12; lateral canthus, n=6, and medial canthus, n=7, and defects<1.04cm2 showed good outcomes. Anatomic location, eyelid margin involvement and age were not significantly associated with esthetics outcomes.49 Lowry et al.50 reported its use on 59 patients with defects ranging from 3.3mm up to 22.3mm on the periocular region: medial canthus, n=32; lower eyelid, n=20; upper eyelid, n=4; glabella, n=2; and nasojugal fold, n=1. Five defects involved the eyelid margin, and 3 the canalicular system. Favorable functional and esthetic outcomes were achieved in 83% of individuals, with complications occurring in 10/59 patients: ectropion, medial canthal webbing, trichiasis, eyelid notching and hypertrophic scarring, with only 2 requiring secondary repair. Trieu et al.51 reported the use of SIH on the lower eyelid in small defects (0.09cm2 up to 1.38cm2) on 17 patients, with 100% patient satisfaction with the esthetic outcomes achieve. There was only 1 case of trichiasis, and all defects healed by week 2.

Overall, use of SIH in the periorbital region can be safe and effective, especially if the defect is <1cm2 (or <25% of the eyelid) and superficial, regardless of location and eyelid involvement51.

Scalp and foreheadSIH represents a valid primary reconstructive option for forehead and scalp defects, especially in balding scalps52. Becker et al.53 evaluated 135 patients who had full-thickness defects on the forehead. Defects in the central area healed with atrophic, white, and depressed scars, while defects in the glabellar and temporal regions healed better. SIH can be used for large defects on the scalp (>10cm in diameter).54 Regarding healing time, Daly et al. reported a re-epithelization time of 3–4 weeks for smaller wounds (<2cm diameter) and 6 weeks for intermediate wounds (2cm up to 5cm)52. For wounds with exposed bone, especially without periosteum, SIH may be preferable to surgical reconstruction. In such cases, fenestration of the bone cortex promotes granulation tissue and subsequent healing55. Biosynthetic collagen dressings can also be useful56.

In a study with 205 patients undergoing SIH after MMS on the scalp and forehead, 38 patients exhibited bone exposure with a mean area of 10.7cm2. In those cases, mean time to re-epithelialize was 13 vs 7 weeks when the periosteum was preserved. A similar retrospective study with 41 patients with defects with exposed bone on the scalp, forehead or temple showed a mean time to complete granulation of 92 days (186 days for re-epithelization). Good cosmesis was achieved in 57% of cases and no SSI were reported57. In a study of 91 patients with exposed bone defects on the head healed by SIH, only 2.7% of patients experienced SSI, and 0% cases of osteomyelitis were observed19.

Defects on the eyebrows and above left minimal distortion, even in cases of large and deep defects. However, 4 large defects affecting contiguous subunits and/or involving muscle, periosteum, or bone caused eyebrow distortion53. A smaller case series showed similar results58, with good cosmesis, although telangiectasias were relatively common.

CheekConvex anatomical regions, such as the cheek, are traditionally considered not optimal for SIH. However, a study on 132 wounds on the cheek59 (wound size from 6.3cm2 up to 32.5cm2, and depth up to subcutaneous layer, parotid gland or muscular structures in nasolabial folds) showed that most defects healed after 3 to 6 weeks. SIH in the nasolabial fold and preauricular areas achieved excellent results59 (Fig. 5). Conversely, only half of the defects in the cheek medial area healed well, and defects on the mandibular or zygomatic areas healed unpredictability and often poorly13. Retraction tended to occur when defects extended far onto the lip or on zygomatic defects extending toward the lower eyelid59.

HandsA case-series of 48 patients undergoing SIH on the dorsal aspect of the hands (n=37) or fingers (n=11) after MMS (0.8–6cm) showed no functional changes, with most patients reporting excellent or good cosmesis. None of the defects crossed joints or involved exposed tendons without paratenon. The authors also mention the combination of SIH plus purse string or partial closures to minimize the area left to SIH18. Another case series with 28 full-skin thickness defects involving the fascia or subcutaneous fat, with no tendon exposed and a median size of 2.4cm (1.5cm up to 4.6cm), revealed a median time of healing of 44 days, and a high rate of patient satisfaction. As for AE, overgranulation developed in 12 of the 28 wounds, which resolved after applying a topical corticosteroid and discontinuing hydrocolloid dressing60.

Lower extremitiesThe plantar region can be a complex site to repair. A retrospective study of 25 patients with melanoma on the soles compared 13 patients treated with SIH and 12 repaired using full-thickness skin graft. Estehetic, functional, and clinical outcomes were more favorable with SIH, although wounds took longer to heal (12 vs 8 weeks), without any differences being reported in side effects. Such findings have been previously reported61-63.

Genital areaIn a retrospective study on 20 patients with penile tumors treated with MMS, 80% were left to heal by SIH with good esthetic outcomes64.

ConclusionsSIH represents a straightforward, safe, well-established, and cost-effective1,2,12 method of wound healing6. This approach—characterized by basic outpatient postoperative care—has a low infection rate, preserves local skin architecture, and enables swift visualization and detection of recurrence in the management of recurrent, aggressive, and/or previously treated tumors. Several critical factors, including defect location, size, depth, geometry and color must be meticulously considered to guarantee optimal outcomes.1,38 While smaller or superficial defects in concave areas often yield superior results38, SIH can achieve favorable outcomes in the periocular region, lips, and nose too, including the alar region, ears and dorsal aspect of hands. Furthermore, SIH can achieve better functional and esthetic outcomes than flaps or grafts.1,50,51 Moreover, SIH allows potential subsequent surgical procedures or combinations with other closure techniques. The major drawbacks of SIH are the long postoperative care needed, particularly with large defects, and wound retraction, particularly at free anatomical borders, while primary contraindication remains the exposure of sensitive structures, such as nerves and arteries.

Statement of any prior presentationThis study has not previously been presented.

Funding/SupportThe authors involved have reported no relevant financial relationships with commercial interest(s).