Lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET) is a rare form of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) with a controversial connection to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). We conducted a retrospective study with 34 LET patients in a Spanish tertiary referral center from 2007 to 2019. Most were women [52.9% (18/34)], with a median age of 53.5 years. Autoimmune or rheumatologic disorders were reported in 52.9% (18/34) of cases, and other CLE variants in 26.5% (9/34). SLE occurred in 8.82% (3/34), while 64.7% (22/34) had autoantibodies. Immunohistochemical CD123 testing tested positive in 75.9% (22/34), while direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed positivity in 31.8% (7/22) of cases. Treatment included topical agents (100%), antimalarials (73.5%), oral corticosteroids (23.5%), and immunosuppressants (14.7%). All achieved clinical remission, but a delayed response (>3 months) was linked to SLE (p=0.002) and anti-DNA antibodies (p=0.003).

LET usually associates with autoimmune disorders and autoantibodies. CD123 and DIF aid diagnosis, and systemic treatment may be needed, especially with SLE and anti-DNA antibodies.

El lupus eritematoso túmido (LET) es una forma rara de lupus eritematoso cutáneo (LEC) con vínculos inciertos con el lupus eritematoso sistémico (LES). Estudiamos retrospectivamente a 34 pacientes con LET entre 2007 y 2019. La mayoría eran mujeres [52,9% 18/34)] (mediana de edad de 53,5 años). El 52,9% (18/34) presentaba trastornos autoinmunitarios o reumatológicos, y el 26,5% (9/34), otras variantes de LEC. Tres pacientes (8,2%) desarrollaron LES. El 64,7% (22/34) presentaba autoanticuerpos. La inmunohistoquímica de CD123 fue positiva en el 75,9% (22/34), y la inmunofluorescencia directa (IFD) en el 31,8% (7/22). El tratamiento incluyó agentes tópicos (100%), antipalúdicos (73,5%), corticosteroides orales (23,5%) y otros inmunosupresores (14,7%). Todos alcanzaron la remisión clínica. Una respuesta tardía (>3 meses) se asoció a la presencia de LES (p=0,002) y de anticuerpos anti-ADN (p=0,003).

El LET suele asociarse con trastornos autoinmunitarios y autoanticuerpos. CD123 e IFD podrían ser útiles para el diagnóstico. Puede requerirse tratamiento sistémico, especialmente en casos de LES y presencia de anticuerpos anti-ADN.

Lupus erythematosus tumidus (LET) is a rare and controversial variant of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE), characterized by non-scarring erythematous and edematous papules and plaques predominantly on the face and trunk. It has been reported that its association with autoimmune disorders or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is extremely rare.1,2 There are only a few large series described in the literature.1–3 We sought to describe the clinical–epidemiological and histological features, direct immunofluorescence (DIF) findings, and therapeutic response of LET.

Materials and methodsPatientsWe conducted a retrospective study with LET patients diagnosed in the Department of Dermatology of a Spanish tertiary referral center from January 2007 to May 2019. Clinical–epidemiological features, comorbidities, histological, DIF findings and response to treatment were recorded. Diagnosis of LET was based on clinical characteristics such as the presence of non-scarring erythematous, succulent and edematous papules and plaques located predominantly on sun-exposed areas along with histological features such as dermal edema, perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltration, and interstitial mucin deposition.

Diagnosis of SLE was based on the 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria. All patients were monitored for, at least, 6 months. Response to treatment was defined as early clinical response (ECR) or late clinical response (LCR) when it was achieved within 3 months or after 3 months, respectively.

Lab test resultsAutoantibodies tests were performed using a standard indirect immunofluorescence technique. Anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA), anti-La and anti-Ro were determined by standardized enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays.

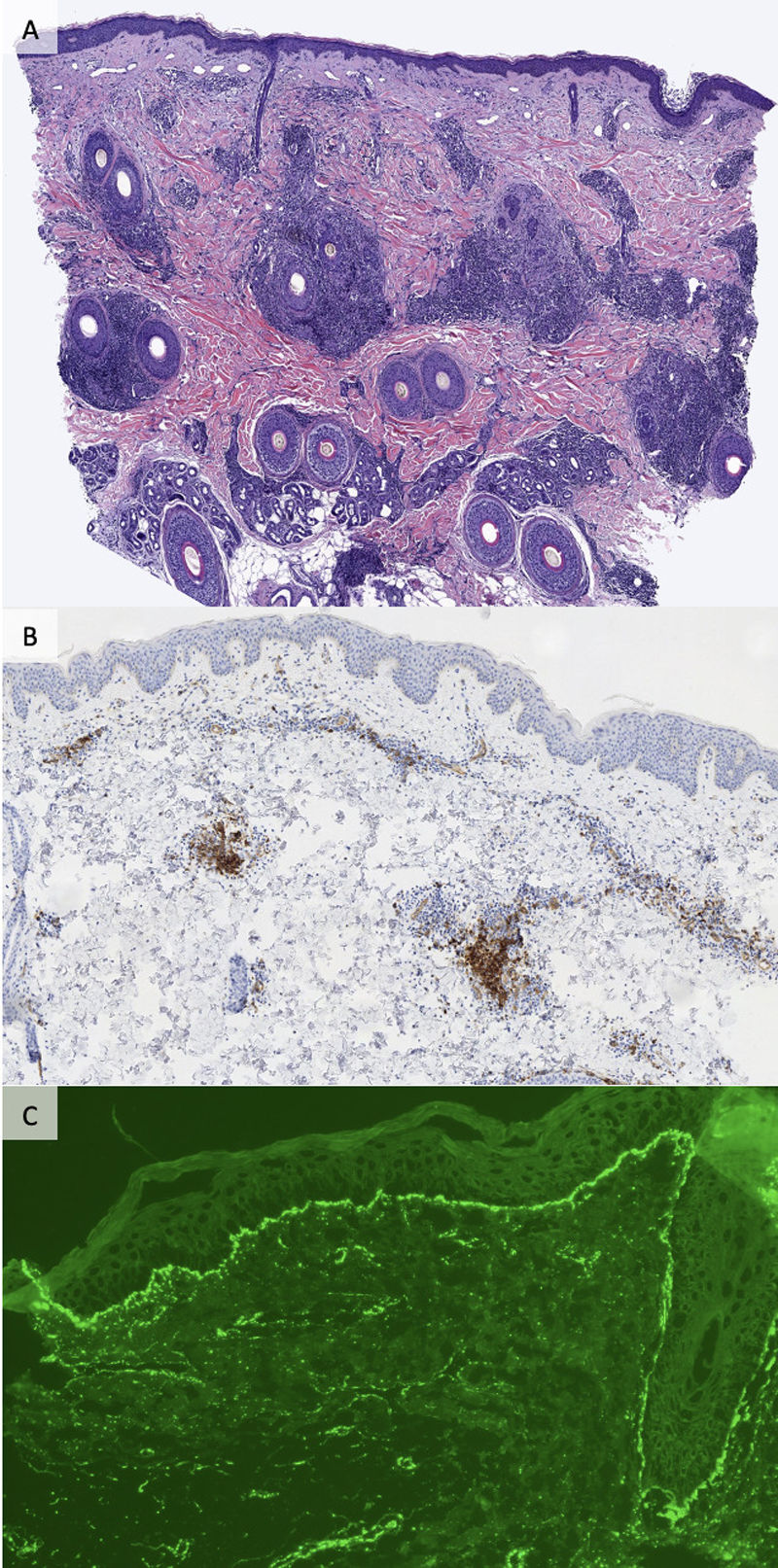

Histopathological and immunohistochemical studiesDermoepidermal junction changes, type and pattern of inflammatory infiltrate, presence of interstitial mucin deposition and reactivity of CD123 immunohistochemical staining were evaluated by an expert dermatopathologist (AGH). Colloidal iron and/or Alcian blue were used to detect the presence of mucin. Positivity for CD123 was defined as the presence of clusters of CD123+ plasmacytoid dendritic cells (PDCs) arranged in aggregates of ≥15 CD123+ PDCs.

Direct immunofluorescenceFour-micrometer thick cryostat sections from cutaneous biopsies obtained from lesional skin were stained with polyclonal fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antibodies against human IgA, IgG, IgM, and C3, as per routine clinical testing.

Statistical analysisClinical–histological characteristics and outcomes were expressed as frequencies. The use of systemic therapy with corticosteroids or immunosuppressants and treatment response were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis One-Way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) test. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

ResultsClinical–epidemiological featuresA total of 34 patients were included (52.9% [18/34] women). The median age was 53.5 years (range, 31–78). The median clinical follow-up was 47 months (range, 6–240). All patients presented with typical lesions of LET (erythematous edematous plaques or papules with no scarring). Lesions were located on the back [(82.4%) (28/34)] and face [(58.8%) (20/34)] in most patients. The median diagnostic delay was 6 months (range, 1–312).

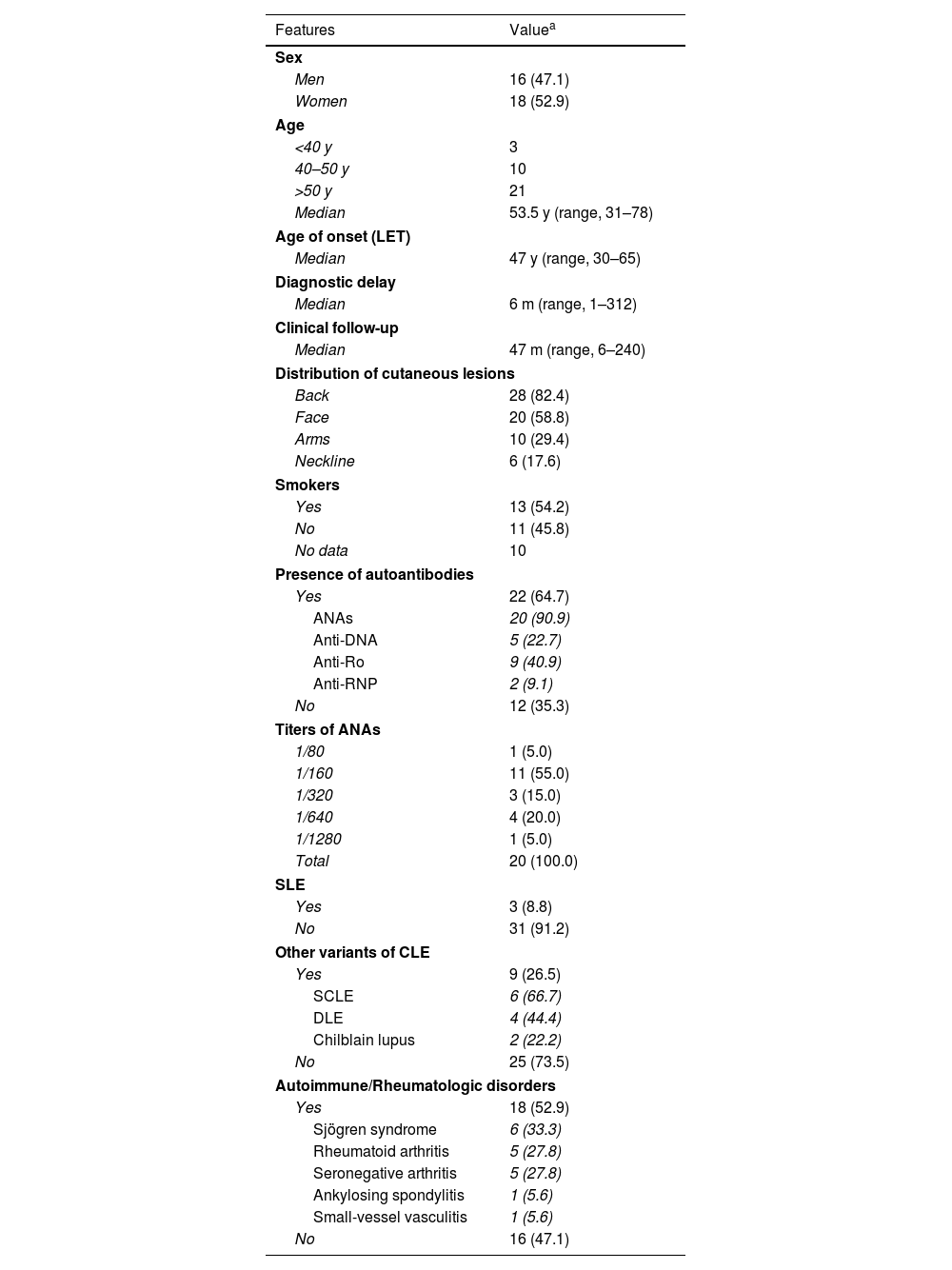

Comorbidities (Table 1): autoimmune or rheumatologic disorders were found in 52.9% (18/34) of the patients, Sjögren's syndrome was the most frequently detected [17.4% (6/34) of cases). Other variants of CLE were observed in 26.5% (9/34) of patients. Of these, 66.7% (6/9) of cases were diagnosed with subacute CLE (SCLE), 44.4% (4/9) with discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) and 22.2% (2/9) with chilblain lupus. Association with SLE—according to the 2019 EULAR/ACR classification criteria—was observed in 8.82% (3/34) of individuals: 2 had concomitant joint and kidney involvement and 1, lung and joint involvement. At least 1 positive autoantibody was detected in 64.7% (22/34) of patients: positive antinuclear antibodies (ANA) (titers>1/80) in 90.9% (20/22) of these cases, anti-DNA antibodies in 22.7% (5/22), anti-Ro, 40.9% (9/22) and anti-RNP in 9.1% (2/22) (Table 1).

Clinical–epidemiological characteristics, autoimmune/rheumatologic comorbidities and presence of autoantibodies in patients with lupus erythematosus tumidus.

| Features | Valuea |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Men | 16 (47.1) |

| Women | 18 (52.9) |

| Age | |

| <40 y | 3 |

| 40–50 y | 10 |

| >50 y | 21 |

| Median | 53.5 y (range, 31–78) |

| Age of onset (LET) | |

| Median | 47 y (range, 30–65) |

| Diagnostic delay | |

| Median | 6 m (range, 1–312) |

| Clinical follow-up | |

| Median | 47 m (range, 6–240) |

| Distribution of cutaneous lesions | |

| Back | 28 (82.4) |

| Face | 20 (58.8) |

| Arms | 10 (29.4) |

| Neckline | 6 (17.6) |

| Smokers | |

| Yes | 13 (54.2) |

| No | 11 (45.8) |

| No data | 10 |

| Presence of autoantibodies | |

| Yes | 22 (64.7) |

| ANAs | 20 (90.9) |

| Anti-DNA | 5 (22.7) |

| Anti-Ro | 9 (40.9) |

| Anti-RNP | 2 (9.1) |

| No | 12 (35.3) |

| Titers of ANAs | |

| 1/80 | 1 (5.0) |

| 1/160 | 11 (55.0) |

| 1/320 | 3 (15.0) |

| 1/640 | 4 (20.0) |

| 1/1280 | 1 (5.0) |

| Total | 20 (100.0) |

| SLE | |

| Yes | 3 (8.8) |

| No | 31 (91.2) |

| Other variants of CLE | |

| Yes | 9 (26.5) |

| SCLE | 6 (66.7) |

| DLE | 4 (44.4) |

| Chilblain lupus | 2 (22.2) |

| No | 25 (73.5) |

| Autoimmune/Rheumatologic disorders | |

| Yes | 18 (52.9) |

| Sjögren syndrome | 6 (33.3) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 5 (27.8) |

| Seronegative arthritis | 5 (27.8) |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 1 (5.6) |

| Small-vessel vasculitis | 1 (5.6) |

| No | 16 (47.1) |

LET, lupus erythematosus tumidus; y, years; m, months; ANAs, antinuclear antibodies; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SCLE, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus; DLE, discoid lupus erythematosus.

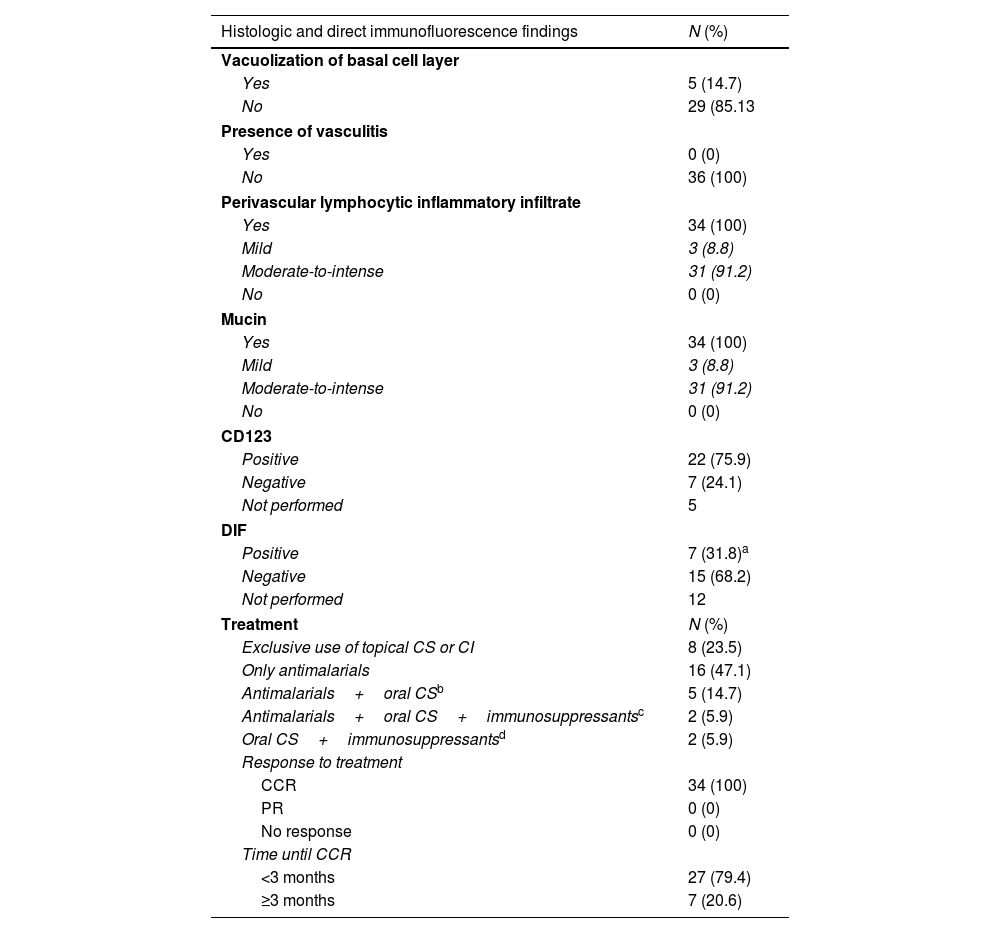

Perivascular inflammatory lymphocytic infiltrate and the presence of interstitial mucin was evidenced in 100% (34/34) of the samples (Table 2). Mild involvement of the dermoepidermal junction with focal vacuolization of the basal layer was observed in 14.7% (5/34) of cases. Immunohistochemical study with CD123 was conducted in 29 specimens, showing positivity in 75.9% (22/29). DIF was performed in 64.7% (22/34) of cases turning out positive in 31.8% (7/22). The most common patterns observed were homogeneous deposit of IgG and granular deposit of C3 at the basement membrane (5/7).

Histologic and direct immunofluorescence findings and therapy required to achieve complete clinical response in patients with lupus erythematosus tumidus.

| Histologic and direct immunofluorescence findings | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Vacuolization of basal cell layer | |

| Yes | 5 (14.7) |

| No | 29 (85.13 |

| Presence of vasculitis | |

| Yes | 0 (0) |

| No | 36 (100) |

| Perivascular lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate | |

| Yes | 34 (100) |

| Mild | 3 (8.8) |

| Moderate-to-intense | 31 (91.2) |

| No | 0 (0) |

| Mucin | |

| Yes | 34 (100) |

| Mild | 3 (8.8) |

| Moderate-to-intense | 31 (91.2) |

| No | 0 (0) |

| CD123 | |

| Positive | 22 (75.9) |

| Negative | 7 (24.1) |

| Not performed | 5 |

| DIF | |

| Positive | 7 (31.8)a |

| Negative | 15 (68.2) |

| Not performed | 12 |

| Treatment | N (%) |

| Exclusive use of topical CS or CI | 8 (23.5) |

| Only antimalarials | 16 (47.1) |

| Antimalarials+oral CSb | 5 (14.7) |

| Antimalarials+oral CS+immunosuppressantsc | 2 (5.9) |

| Oral CS+immunosuppressantsd | 2 (5.9) |

| Response to treatment | |

| CCR | 34 (100) |

| PR | 0 (0) |

| No response | 0 (0) |

| Time until CCR | |

| <3 months | 27 (79.4) |

| ≥3 months | 7 (20.6) |

N, number; DIF, direct immunofluorescence; CS, corticosteroids; CI, calcineurin inhibitors; CCR, complete clinical response; PR: partial response.

5 cases showed a homogeneous deposit of IgG and granular C3 at the basement membrane. In 1 case there were granular deposits of C3 around the vessels and in another sample, perivascular granular deposits of IgM.

2 individuals suffered from systemic lupus erythematosus, and other, from subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus.

Although all patients achieved a complete clinical response (CCR), multiple therapeutic agents were required. ECR was observed in 79.4% (27/34) of the patients, and LCR in 26.5% (9/34) of cases. All patients with SLE (3/3) and 80% (4/5) of the individuals with anti-DNA antibodies presented LCR.

All individuals received topical treatment (corticosteroids and/or calcineurin inhibitors). CCR was achieved exclusively with topical treatment in 23.5% (8/34). All of them showed ECR. Antimalarials were prescribed in 73.5% of cases (25/34), oral corticosteroids in 23.5% (8/34), and immunosuppressants in 14.7% (5/34) [mycophenolate (1/5), methotrexate (1/5), azathioprine+methotrexate (1/5) and mycophenolate+methotrexate (2/5)].

Regarding patients who received antimalarials, 45.7% (16/25) received them exclusively. Partial response (PR) was observed in 81.3% (13/16) and CCR in 18.7% (3/16); 20% (5/25) received antimalarial and oral corticosteroids, with PR in 40% (2/5) and CCR in 60% (3/5). Two patients received antimalarials and immunosuppressants (methotrexate or mycophenolate) and achieved CCR; another 2 patients, antimalarials, oral corticosteroids and immunosuppressants (methotrexate or mycophenolate), with PR in 1 patient and CCR in the other. Only 1 case was treated exclusively with oral corticosteroids and immunosuppressants (azathioprine and methotrexate since the patient had rheumatoid arthritis) and showed PR.

PR was significantly associated with age<50 years (p=0.034). LCR was significantly associated with the presence of SLE (p=0.002) and anti-DNA antibodies (p=0.003). Therapeutic response was not associated with sex, habitual smoking, age of LET presentation, concomitance with other types of CLE or autoimmune diseases, or presence of antinuclear antibodies, anti-Ro or anti-RNP, or positivity of CD123 or immunofluorescence.

DiscussionLET affects men and women in a similar proportion,1,4 which was also observed in our series. Clinical presentation in our series was consistent with data previously described in literature exhibiting non-scarring, erythematous and edematous plaques/papules on the face, trunk and/or upper extremities.5 Regarding the association with autoimmune diseases, it has been reported that LET is rarely associated with SLE or the presence of circulating autoantibodies.1,4,5 However, Schmitt et al.6 reported that >40% of LET patients had positive antinuclear antibodies, and 20% of them presented with SLE. In our series we observed that most patients had circulating autoantibodies, more frequently ANAs (titers>80), and SLE was diagnosed in 9% of cases. Furthermore, other variants of LEC were observed in >25% of patients. Strikingly, autoimmune/rheumatological disorders were observed in half of the individuals. These findings suggest that the autoimmune background in LET can be greater than previously described.

Histological findings in our series were similar to those previously reported, such as the presence of perivascular lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate and mucin deposition in most cases, and changes of the dermoepidermal junction in a minority of specimens,2,4–7 although this rate can be up to 50%.4,8

CD123 staining allows identification of PDCs and can be used in the diagnosis of CLE,9,10 although evidence on its use in LET is scarce.5,10 We observed positivity for CD123 (with a perivascular pattern) in almost 80% of cases with LET. We believe that CD123 can be a useful diagnostic tool in challenging cases of LET.

DIF can be used for the diagnosis of CLE.5,7 While it has been reported that DIF is negative in LET, positivity of DIF has been described in a variable percentage of cases, from <10%2 up to >50%.5,7 In our series, positivity by DIF was observed in >30% of specimens. Homogeneous IgG deposit and granular deposit of C3 in the basement membrane were the most frequent patterns. We consider that DIF can be a useful technique in the diagnosis of LET and help to differentiate it from other dermatoses with similar clinical presentation.5 However, these results should be interpreted with caution, as DIF tested positive in only 7 out of 22 patients.

Regarding treatment, most authors suggest that clinical response is good and rapid,1 and that LET can even resolve spontaneously in up to 40% of cases.6 Photoprotection, topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors are first-line therapies, along with antimalarials.1,4,8 In our series, all patients achieved CCR, although they required diverse therapeutic agents. Exclusively topical treatment led to CCR in <25% of cases. Most patients required systemic treatment, and antimalarials were the most frequently indicated. Excellent responses were observed in most cases. However, one quarter of them required ≥3 months to achieve CCR. Slow improvement of lesions in LET patients has previously been described.7 Strikingly, almost 30% of cases in our series required oral CS or immunosuppressants to achieve CCR. More than half of these patients presented with autoimmune disorders. Age≤50 years, absence of SLE or circulating anti-DNA antibodies were associated with ECR. Given these findings, we consider that, in elderly patients or individuals with SLE or with anti-DNA antibodies, early initiation of systemic treatment could be considered.

Limitations of our study are its retrospective design and the relatively small number of patients included, despite being one of the largest series described to date.

ConclusionsLET may be strongly associated with Autoimmune/Rheumatologic disorders and with the presence of autoantibodies. CD123 and DIF can be useful when diagnosing LET. Use of systemic corticosteroids and immunosuppressants may be necessary, especially for patients with SLE or anti-DNA antibodies.