Atopic dermatitis (AD) is one of the most prevalent skin diseases, but there are numerous knowledge gaps surrounding the impact this disease has on quality of life (QoL), mental health, and out-of-pocket expenses involved in the management of AD. The available scientific evidence on the multidimensional burden of AD is usually based on studies with measures reported by patients themselves.

MethodsIn this context, the MEASURE-AD trial was developed as a cross-sectional, multicenter, multinational trial using patient- and physician-reported measures to characterize the multidimensional burden of AD in adults with moderate-to-severe AD.

ResultsThis paper presents the results of the Spanish cohort. We found that Spanish adults with moderate-to-severe AD and high EASI score (21.1-72) had a significantly increased disease burden, high severity of symptoms such as itch and sleep disturbances, impaired mental health and QoL, higher use of health care resources, and more out-of-pocket expenses than patients with low EASI scores (0-7 or 7.1-21).

ConclusionsThis study provides information to better understand disease burden, and identify aspects to be improved in the management of AD.

La dermatitis atópica (DA) es una de las enfermedades cutáneas más prevalentes, pero existen importantes lagunas en la comprensión de su impacto sobre la calidad de vida (CdV) y la salud mental de los pacientes, así como los gastos directos que les ocasiona. La evidencia científica sobre la carga multidimensional de la DA procede habitualmente de estudios en los que se utilizan exclusivamente resultados informados por los pacientes.

MétodosEn este contexto, se diseñó el estudio MEASURE-AD, de tipo transversal, multicéntrico e internacional, con resultados informados por los pacientes y por los facultativos con el fin de describir dicha carga multidimensional en adultos con DA moderada o grave.

ResultadosEn este artículo se presentan los resultados de la cohorte española. Los adultos con DA moderada o grave y EASI entre 21,1 y 72 presentaron una carga significativamente más alta de la enfermedad, síntomas muy intensos, como el prurito y las alteraciones del sueño, afectación de la salud mental y la CdV y mayor consumo de recursos sanitarios y gasto directo que los pacientes con puntuación EASI entre 0-7 o 7,1-21.

ConclusionesEl estudio aporta información para comprender mejor la carga que supone la enfermedad y nos permite identificar qué aspectos conviene mejorar en el manejo de la DA.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that presents with flare-ups and is characterized by intense itching, dryness, and eczema.1,2 AD affects both children and adults and is one of the most prevalent skin diseases worldwide.3 Although its prevalence among Spanish adults goes from 0.028%4 up to 0.085%,5 recent data suggest it is underestimated.6 Despite being one of the most disabling skin diseases,7–9 its impact on adult patients—especially in moderate-to-severe cases—remains poorly understood.9,10 In fact, it has been reported that the disease burden on patients is directly related to physical signs and symptoms such as itching9,11 and indirectly related to sleep disturbances,12,13 mental health,14,15 and daily activities, all contributing to a decline in quality of life (QoL).16 Additionally, AD poses a significant public health burden from an economic perspective, as it has been associated with high direct and indirect costs, and increased health care resource utilization.9,10,17,18

Traditionally, research has focused more on the signs and symptoms of AD than on its impact on QoL and other indirect effects. Although this information often comes from patient-reported outcomes (PROs),10 discrepancies have recently been observed between patient-reported AD outcomes and those reported by physicians.6

In this context, the MEASURE-AD study was conducted to include both patient-reported and physician-reported outcomes to obtain a more objective description of the multidimensional burden of AD and to minimize biases in PROs.19 This article presents the results from the Spanish cohort of the MEASURE-AD study, allowing us to describe the multidimensional burden of the disease, treatment patterns, and use of health care resources in Spanish adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD.

Materials and methodsStudy design and patientsThe MEASURE-AD study is a cross-sectional, multicenter, and multinational study that included adult and adolescent patients with moderate-to-severe AD after obtaining informed consent.19 The study was conducted in full compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki, the Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices (GPP) of the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology (ISPE), good clinical practice standards and current legislation and regulations. Patients with AD attending regular follow-up at their dermatology clinic or office were recruited consecutively over a 6-month period to control for selection bias. Patients who gave their consent, were older than 12 years, had a confirmed diagnosis of AD, were receiving or eligible for systemic treatment, and had available pharmacological history from the last 6 months were included. Participants in interventional trials were excluded.

TreatmentsUpon inclusion, information about current and past treatments was collected. The treatments evaluated included marketed drugs with a therapeutic indication for AD at the time of the study. These treatments were categorized exclusively and hierarchically into 4 groups: 1) topical products (corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors); 2) classic systemic therapy (including immunomodulatory treatment and excluding cyclosporine); 3) cyclosporine; and 4) biological therapy (dupilumab).

Severity of atopic dermatitisPatients were stratified according to AD severity using the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI)20: absent (0); almost absent (0.1 up to 1.0); mild (1.1 up to 7.0); moderate (7.1 up to 21.0); severe (21.1 up to 50.0); and very severe (50.1 up to 72.0).20–22 For the purposes of this analysis, EASI intervals were regrouped into 3 categories: EASI-0-7; EASI-7.1-21; and EASI-21.1-72.22

Outcome variablesDuring the study visit, PROs and physician-reported outcomes were documented using a validated questionnaire with scales and independent questions to describe the multidimensional burden of AD, including severity and disease control, sleep quality, QoL, treatment satisfaction, direct costs, and use of health care resources.

Primary endpoints included: 1) assessing the impact of itching using the Worst Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (WP-NRS) within the last 24hours, categorized as WP-NRS-0-3, WP-NRS-4-6, and WP-NRS-7-10, and 2) determining the impact of AD on QoL using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI).23,24

Secondary endpoints included: 1) determining sleep quality, evaluated by the response to the question, “In the past week, how many nights did you have trouble sleeping?” on a scale from 1 (little, 1 night) to 7 (a lot, every night of the week); 2) measuring mental health impact using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS);25 3) estimating the use of health care resources through the number of AD-related dermatology visits and consultations over the past 6 months; 4) evaluating direct costs as the average annual individual expenditure on health care, hygiene, and self-care products, and 5) determining patient satisfaction with current treatments, grouping responses into 2 categories: completely agree and others (partially and completely disagree).

Statistical analysisThe study population was characterized using descriptive statistics for centrality and dispersion for quantitative variables—median/range or mean/standard deviation—and proportions and frequencies for categorical variables. Patients were categorized based on their treatment satisfaction into 2 groups and according to their EASI score into 3 groups. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square tests and multinomial analysis, and continuous variables using Kruskal-Wallis and Wilcoxon tests. P-values were adjusted with Holm-Bonferroni correction. The analysis was conducted using R software (v4.1.1, R Bioconductor).

ResultsCharacteristics of the study populationThe analysis included a total of 95 patients from the 9 Spanish centers participating in the MEASURE-AD study. The median (range) age was 29 years (16–66), and 50.5% of participants were men. The median (IQR) body mass index was 24.3 (16.8–42.8).

Approximately 75% of the patients had moderate-to-severe AD at inclusion. Specifically, 25.26% of patients had EASI scores from 0 up to 7; 20% EASI scores from 7.1 up to 21; and 54.73% EASI scores from 21.1 up to 72.

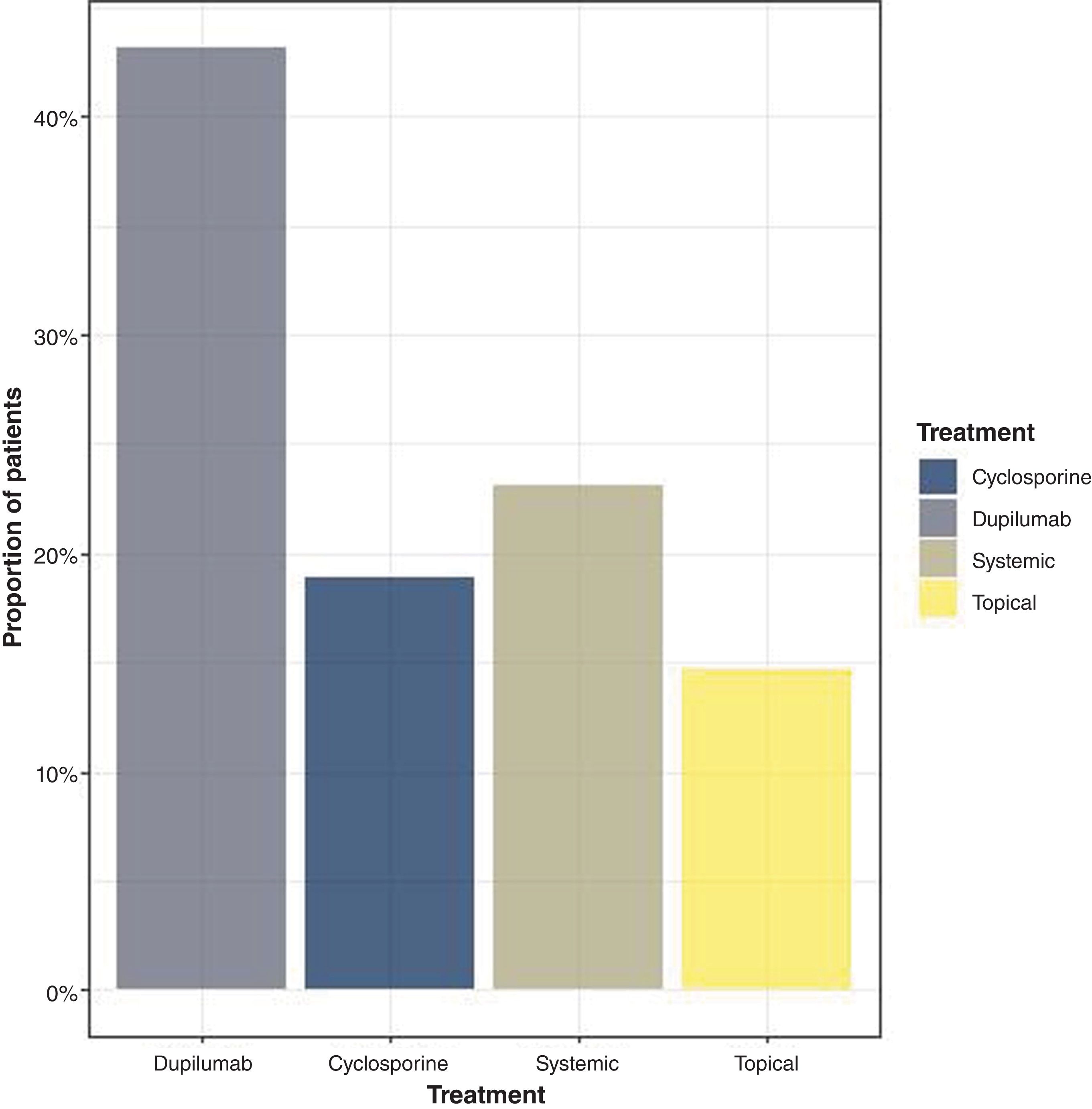

Regarding the treatments used at the time of inclusion, 43.15% were on biological therapy, 18.94% on cyclosporine, 23.15% on systemic treatment, and 14.73% on topical treatment (fig. 1).

The mean (SD) total exposure to each treatment (past and current) was 100.9 days (211.2) for biologicals, 315.0 days (729.6) for cyclosporine, 982.1 days (1548.8) for systemic therapy, and 696.6 days (1031.8) for topical treatment.

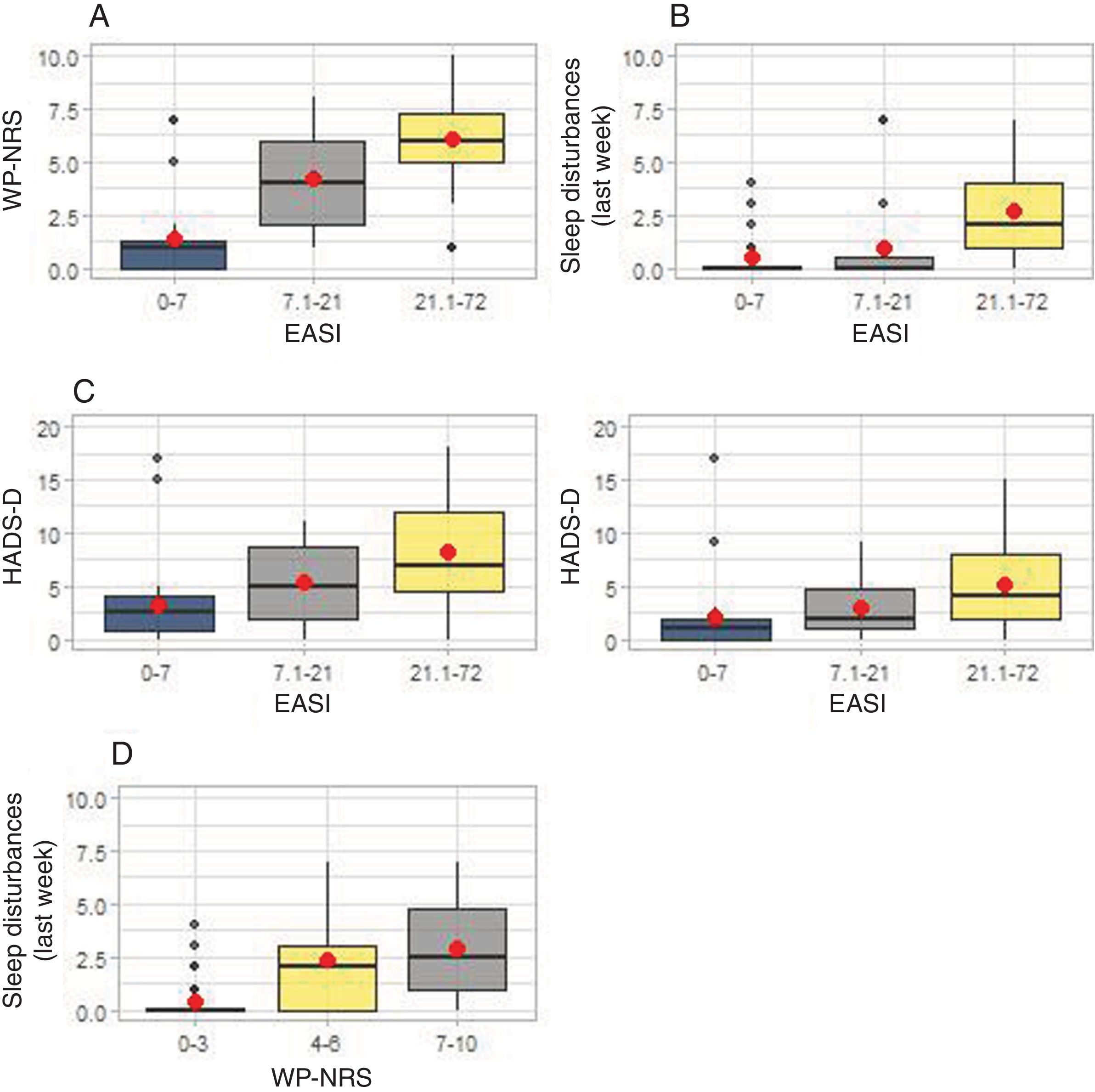

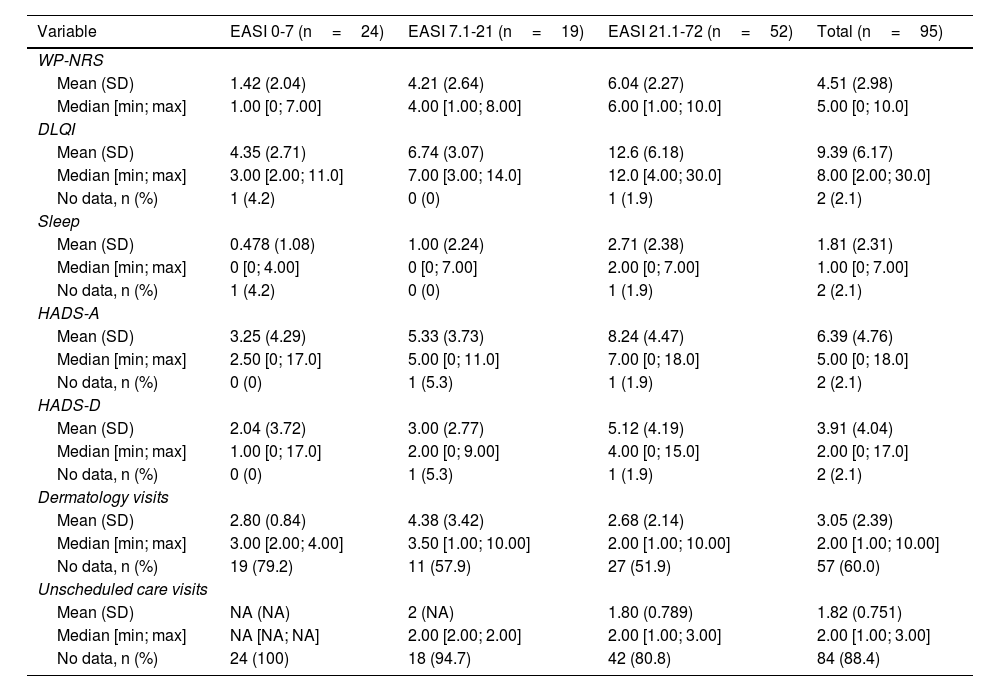

Description of disease burden related to itching, sleep, and mental healthItching and sleepItching increased significantly with disease severity, as measured by the EASI (Table 1) (p<0.001) (fig. 2A). Patients with EASI-21.1-72 experienced more itching than those with EASI-7.1-21 (p=0.013) and EASI-0-7 (p<0.001), and patients with EASI-7.1-21 reported more itching than those with EASI-0-7 (p<0.001).

Analysis of variables by subgroups defined according to the EASI score.

| Variable | EASI 0-7 (n=24) | EASI 7.1-21 (n=19) | EASI 21.1-72 (n=52) | Total (n=95) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WP-NRS | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.42 (2.04) | 4.21 (2.64) | 6.04 (2.27) | 4.51 (2.98) |

| Median [min; max] | 1.00 [0; 7.00] | 4.00 [1.00; 8.00] | 6.00 [1.00; 10.0] | 5.00 [0; 10.0] |

| DLQI | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 4.35 (2.71) | 6.74 (3.07) | 12.6 (6.18) | 9.39 (6.17) |

| Median [min; max] | 3.00 [2.00; 11.0] | 7.00 [3.00; 14.0] | 12.0 [4.00; 30.0] | 8.00 [2.00; 30.0] |

| No data, n (%) | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) | 2 (2.1) |

| Sleep | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 0.478 (1.08) | 1.00 (2.24) | 2.71 (2.38) | 1.81 (2.31) |

| Median [min; max] | 0 [0; 4.00] | 0 [0; 7.00] | 2.00 [0; 7.00] | 1.00 [0; 7.00] |

| No data, n (%) | 1 (4.2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) | 2 (2.1) |

| HADS-A | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 3.25 (4.29) | 5.33 (3.73) | 8.24 (4.47) | 6.39 (4.76) |

| Median [min; max] | 2.50 [0; 17.0] | 5.00 [0; 11.0] | 7.00 [0; 18.0] | 5.00 [0; 18.0] |

| No data, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (1.9) | 2 (2.1) |

| HADS-D | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.04 (3.72) | 3.00 (2.77) | 5.12 (4.19) | 3.91 (4.04) |

| Median [min; max] | 1.00 [0; 17.0] | 2.00 [0; 9.00] | 4.00 [0; 15.0] | 2.00 [0; 17.0] |

| No data, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (1.9) | 2 (2.1) |

| Dermatology visits | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 2.80 (0.84) | 4.38 (3.42) | 2.68 (2.14) | 3.05 (2.39) |

| Median [min; max] | 3.00 [2.00; 4.00] | 3.50 [1.00; 10.00] | 2.00 [1.00; 10.00] | 2.00 [1.00; 10.00] |

| No data, n (%) | 19 (79.2) | 11 (57.9) | 27 (51.9) | 57 (60.0) |

| Unscheduled care visits | ||||

| Mean (SD) | NA (NA) | 2 (NA) | 1.80 (0.789) | 1.82 (0.751) |

| Median [min; max] | NA [NA; NA] | 2.00 [2.00; 2.00] | 2.00 [1.00; 3.00] | 2.00 [1.00; 3.00] |

| No data, n (%) | 24 (100) | 18 (94.7) | 42 (80.8) | 84 (88.4) |

DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; SD: standard deviation; EASI: Eczema Area and Severity Index; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HADS-A: HADS Anxiety subscale; HADS-D: HADS Depression subscale; NA: not available; WP-NRS: Worst Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale.

Impact of atopic dermatitis on pruritus, sleep quality, and mental health. In (A), the differences between the median WP-NRS scores (Worst Pruritus Numeric Rating Scale) are shown for each EASI group (Eczema Area and Severity Index). In (B), sleep disturbances are shown for each EASI group. In (C), the differences in the median scores of the HADS subscales (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale) are shown for each EASI group. In (D), sleep disturbances are shown for each WP-NRS group.

Additionally, sleep quality significantly differed among EASI groups (p<0.001). Patients with EASI-21.1-72 reported worse sleep quality than those with EASI-7.1-21 (p=0.001) and EASI-0-7 (p<0.001), while no significant differences were detected between EASI-7.1-21 and EASI-0-7 groups (p=0.672) (fig. 2B).

When studying the association between WP-NRS groups and sleep disturbances, significant differences were seen (p<0.001). A total of 32% out of the 95 patients had WP-NRS scores from 7 up to 10, 28% WP-NRS scores from 4 up to 6, and 40% WP-NRS scores from 0 up to 3. Patients with WP-NRS scores from 7 up to 10 (p<0.001) and from 4 up to 6 (p<0.001) reported more sleep disturbances than those with scores from 0 up to 3, although no differences were reported between the WP-NRS-4-6 and WP-NRS-7-10 groups (p=0.29) (fig. 2D).

Mental healthThe severity of AD was associated with higher HADS-A scores (p<0.001). Patients with EASI-21.1-72 had significantly higher HADS-A scores than those with EASI-7.1-21 (p=0.038) and EASI-0-7 (p<0.001). Patients with EASI-7.1-21 also showed significantly higher scores than those with EASI-0-7 (p=0.038) (fig. 2C). According to the HADS-A scale, symptoms appear when the score is ≥8 (25). In our population, 34/93 patients (36.5%) had scores ≥8, 74% of whom (25/34) came from the EASI-21.1-72 group.

AD severity was also associated with higher HADS-D scores. Specifically, patients with EASI-21.1-72 had higher HADS-D scores than those with EASI-0-7 (p=0.001). There were no significant differences between patients with EASI-21.1-72 and EASI-7.1-21, or between EASI-7.1-21 and EASI-0-7 (fig. 2C). Overall, 18/93 patients (19.35%) had scores ≥8, 83% of whom (15/18) came from the EASI-21.1-72 group.

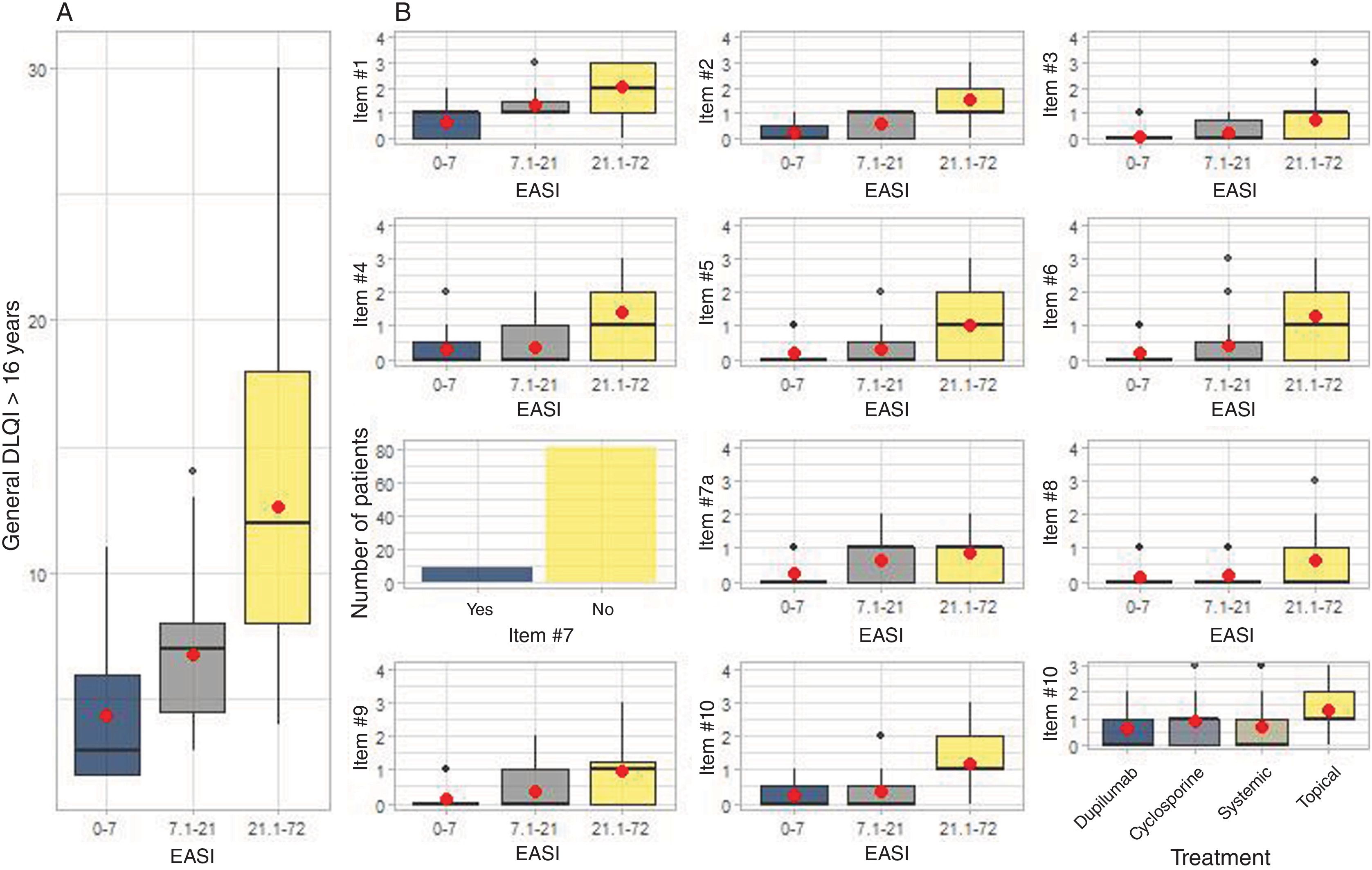

Health-related quality of lifeMedian DLQI scores were significantly higher among patients with higher EASI values (Table 1). Patients with EASI-21.1-72 had significantly higher scores than those with EASI-7.1-21 (p<0.001) and EASI-0-7 (p<0.001). Additionally, patients with EASI-7.1-21 had significantly higher scores than those with EASI-0-7 (p=0.005) (fig. 3A).

Impact of atopic dermatitis on quality of life according to the DLQI. In (A), the differences between the median DLQI scores (Dermatology Life Quality Index) are shown for each EASI group (Eczema Area and Severity Index). In (B), the analysis of each individual question is shown for each EASI group, and for question #10, by treatment type.

DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; EASI: Eczema Area and Severity Index.

The meaning of each question is: question #1: symptoms and feelings; question #2: embarrassment and discomfort; question #3: activities of daily living; question #4: clothing; question #5: social and leisure activities; question #6: sports; questions #7 and #7a: work and study; question #8: relationship problems with partners or friends; question #9: sexual difficulties; question #10: treatments.

Patients with EASI-21.1-72 also reported that AD significantly affected all individual items of the DLQI (p<0.001) (fig. 3B). No differences were detected among different treatment groups in the analysis of question 10 of the DLQI: “In the past 7 days, has your skin treatment been a problem for you?” (fig. 3B).

Use of health care resourcesOverall, 18/95 patients (18.94%) attended unscheduled visits during the study period. Fifteen of these (83.33%) had EASI-21.1-72, and 3 (16.7%) had EASI-7.1-21. Overall, 65/95 patients (68.24%) had seen a dermatologist: 42 patients (63.64%) had EASI-21.1-72, 14 (21.21%) had EASI-7.1-21, and 9 (13.63%) had EASI-0-7. Significant differences were seen among EASI groups and the number of dermatologist visits (p<0.001).

Direct patient costsThe average monthly direct health care costs for patients amounted to €44.74, representing an annual cost of €536.80. Adding the annual direct cost for daily hygiene and personal care needs (€424.32), the average annual cost per patient was nearly €1000 (€964.20).

Significant differences in direct costs were associated with treatments. Patients on topical treatments reported significantly higher health care costs than those on biological (p=0.013) or systemic therapies (p=0.009).

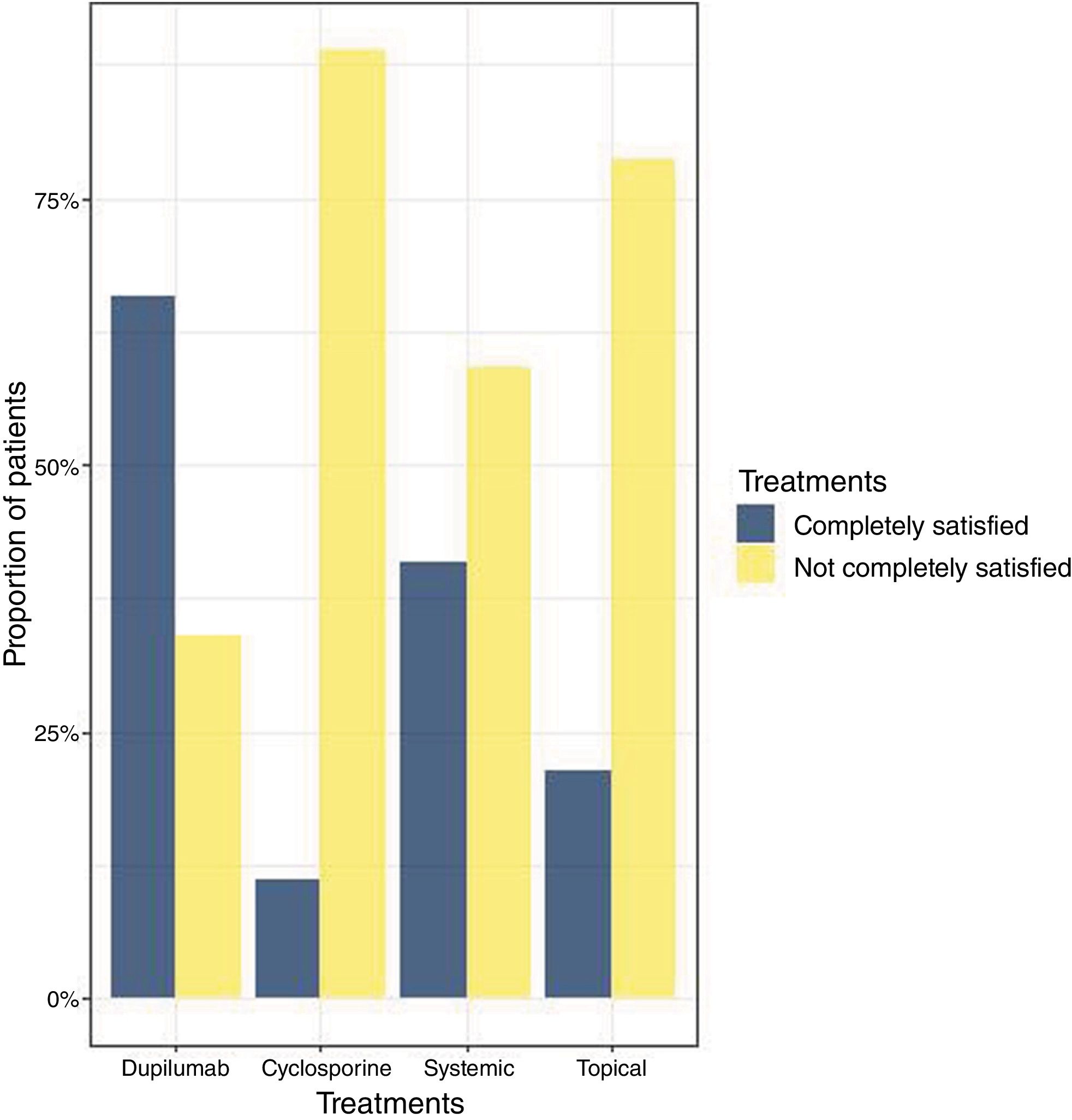

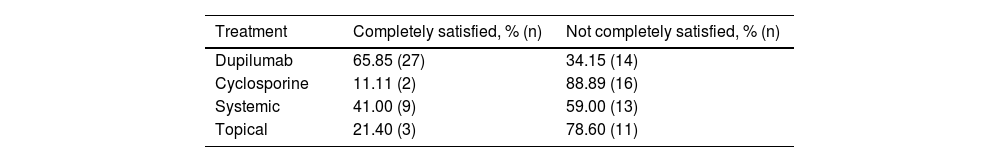

Treatment satisfactionA total of 57% of patients (54/95) felt their current treatment did not sufficiently control their AD, leaving them not completely satisfied (Table 2, fig. 4). A total of 30% of these patients were on cyclosporine, 26% on biological therapy, 24% on systemic therapy, and 20% on topical treatment. A total of 66% out of the 41 patients on biological therapy treatment were fully satisfied vs only 11.11% of patients on cyclosporine, 41% on systemic treatment, and 21.3% on topical treatment who reported being satisfied with their current treatment.

Hypotheses were compared between the “completely satisfied” and “not completely satisfied” groups and revealed that patients on biologics were more satisfied (p=0.008), while those on cyclosporine felt their treatment was insufficient for adequate AD control (p<0.001). No significant differences were observed in the systemic treatment group (p=0.365). Finally, patients from the topical treatment group mostly felt dissatisfied with their treatment (p=0.008).

DiscussionThis real-world study describes the multidimensional burden of AD in Spanish patients with moderate-to-severe AD. The results indicate that in Spain, adults with AD and EASI scores from 21.1 up to 72 experience a significant disease burden, including intense pruritus, sleep disturbances, greater mental health impairment, poorer QoL, greater use of health care resources, and increased direct costs. Regarding sleep quality, depression, and QoL, no significant differences between patients with EASI 7-21.1 and those with EASI 0-7 were ever reported.

Pruritus, the main symptom of AD, is linked to impaired QoL and sleep disturbances, as previously observed.12,26 Moreover, pruritus severity increases with higher EASI scores, affecting sleep, activities of daily living, and QoL, as reflected in DLQI scores and its subscales, consistent with previous studies.10,27

AD patients carry a substantial psychosocial and economic burden. AD may be associated with psychological stress, decreased self-esteem, and lack of sleep.10,12,28,29 These issues are exacerbated by visible lesions, stigmatization, and pruritus, contributing to adverse psychosocial effects and greater use of health care resources.26,30 Of note that former studies.28,29,31–33 have demonstrated that AD is associated with depression, anxiety, and an increased risk of suicidal ideation.33 In this Spanish cohort, anxiety (37%) outweighed depression (20%),31,32 highlighting the importance of evaluating mental health, especially in severe cases of the disease.

In Spain, the economic consequences of AD for patients are substantial. Approximately 20% of patients required unscheduled medical consultations despite being on treatment, and 70% had visited specialists in the previous 6 months, which is consistent with previous research showing increased use of unscheduled and emergency services.34,35 Additionally, AD-related direct costs in our population averaged up to €1000 per year, which is higher than what has been reported by former studies,36,37 possibly due to differences in study design and regional health care systems.35–39

Treatment satisfaction is a matter of concern, as more than half of the patients do not believe their current treatment effectively controls their AD. This may impact QoL and use of health care resources. Specifically, patients on cyclosporine or systemic treatments perceive an insufficient therapeutic effect, underscoring the need for effective pharmacotherapy to improve QoL and reduce the disease burden. At the time of the study, dupilumab was the only approved advanced therapy for AD.

One of the strengths of this study lies in the use of results reported by both patients and physicians, as well as validated scales to determine the severity of AD, mental health impact, and QoL. The EASI score has allowed for the stratification of patients according to disease severity as a way to guide a multidimensional approach. However, the cross-sectional design and recruitment in dermatology clinics limit its scope, as patients treated in other settings may have been excluded.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, this analysis of the MEASURE-AD study provides a real-world snapshot of what Spanish patients with moderate-to-severe AD experience and shows associations among disease severity, mental health, QoL, use of health care resources, and personal direct costs. This underscores the multidimensional burden of the disease and the need for a multidisciplinary approach that considers mental health by integrating other medical specialties. Finally, continued research and the development of new therapeutic and care strategies are essential to minimize the economic and psychosocial burdens of AD.

FundingAbbVie funded the studies and participated in the design, research, analysis, data collection and interpretation, review and approval of its publication. All authors had access to the relevant data and participated in the drafting, review, and approval of this article. The authors have not received any fees or other remuneration for their work.

Conflicts of interestJuan Francisco Silvestre has provided consultancy services and received speaker fees for training activities from Sanofi Genzyme, Regeneron, AbbVie, Galderma, Eli Lilly, Leo Pharma, Pfizer, and Novartis. He has also been the principal investigator in clinical trials sponsored by AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Incyte, Leo Pharma, Novartis, and Pfizer, unrelated to the work presented here.

Ricardo Ruiz Villaverde has provided consultancy services and received speaker fees for training activities from Janssen, AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Lilly, MSD, Sanofi, and UCB. He has also been the principal investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Janssen, AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Lilly, MSD, Sanofi, and UCB.

Bibiana Pérez García has provided consultancy services and received speaker fees for training activities from Sanofi, Genzyme, Regeneron, AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lilly, Galderma, Leo Pharma, Pierre Fabre, Meda Pharma, and FAES Pharma. She has also been the principal investigator in clinical trials sponsored by AbbVie, Sanofi, Lilly, Galderma, and FAES Pharma, unrelated to the work presented here.

Pedro Herranz has provided consultancy services, received speaker fees for training activities, or served as the principal investigator in clinical trials for the following companies: AbbVie, Almirall, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Leo Pharma, Janssen, Novartis, Pfizer, and Sanofi Genzyme (all unrelated to the work presented here).

Javier Jesús Domínguez Cruz has provided consultancy services and received speaker fees for training activities from Sanofi, AbbVie, Almirall, Lilly, Janssen, Novartis, Leo Pharma, and Galderma. He has also been the principal investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Sanofi, AbbVie, Leo Pharma, and Almirall, unrelated to the work presented here.

Rosa Izu Belloso has provided consultancy services and received speaker fees for training activities from Almirall, Sanofi Genzyme, AbbVie, Galderma, Eli Lilly, Leo Pharma, Pfizer, and Novartis. She has also been the principal investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Almirall, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Leo Pharma, Novartis, and Pfizer, unrelated to the work presented here.

Maurizio Gentile is an employee of AbbVie.

Data sharingAbbVie is committed to the responsible communication of data from the clinical trials it sponsors, including allowing access to anonymized data, individual and grouped by trials (data sets for analysis), as well as other documents (protocols and clinical trial reports), as long as these trials are not part of an ongoing or planned registration dossier. Requests for data from clinical trials of unauthorized products and indications are also included.

The data from this clinical trial can be requested by accredited researchers participating in rigorous and independent research; they will be provided after a research proposal and statistical analysis plan are reviewed and approved, following the formalization of a data-sharing agreement. Requests can be submitted at any time, and the data will remain accessible for a period of 12 months, with the possibility of further extensions. More information about the process or how to submit a request can be found at the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our-science/clinical-trials/clinical-trials-data-and-information-sharing/data-and-information-sharing-with-qualified-researchers.html

We wish to thank Dr. Laura Vilorio Marqués (Medical Statistics Consulting, Valencia, Spain) for the technical and analytical assistance provided in the drafting of this manuscript.