Visits for skin conditions are very common in pediatric primary care, and many of the patients seen in outpatient dermatology clinics are children or adolescents. Little, however, has been published about the true prevalence of these visits or about their characteristics.

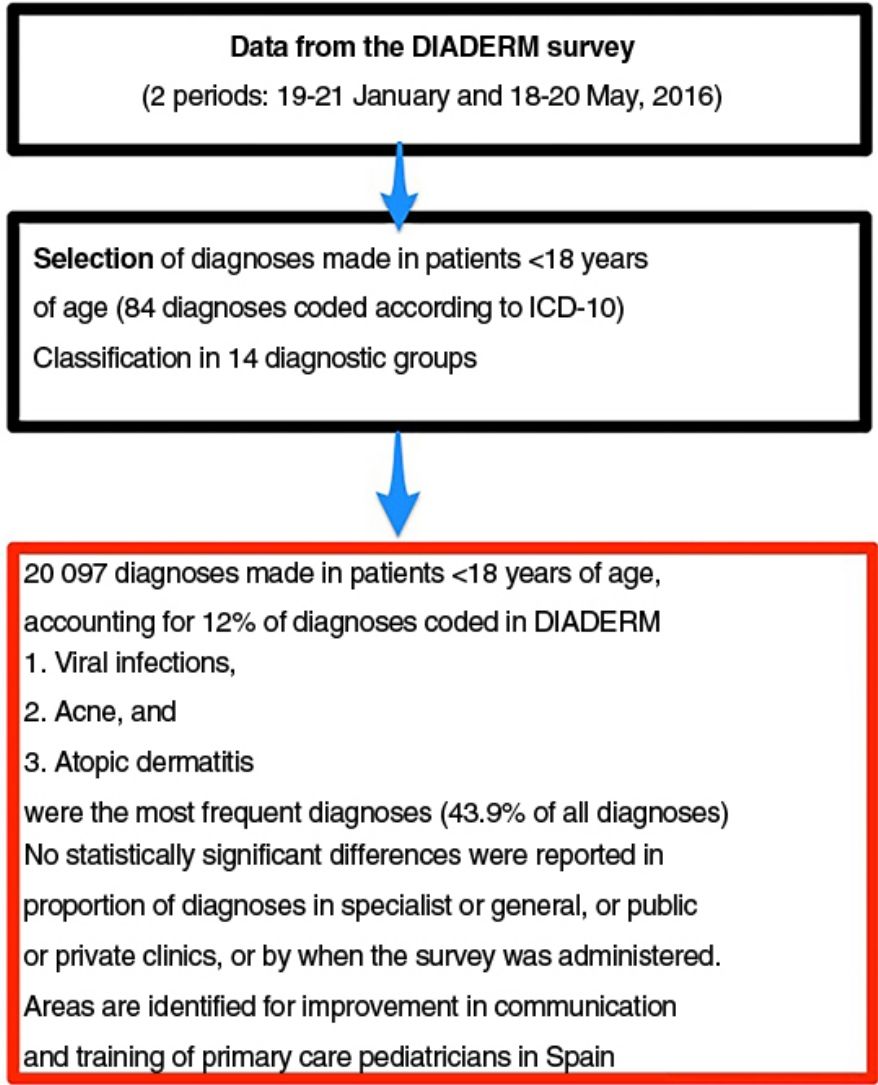

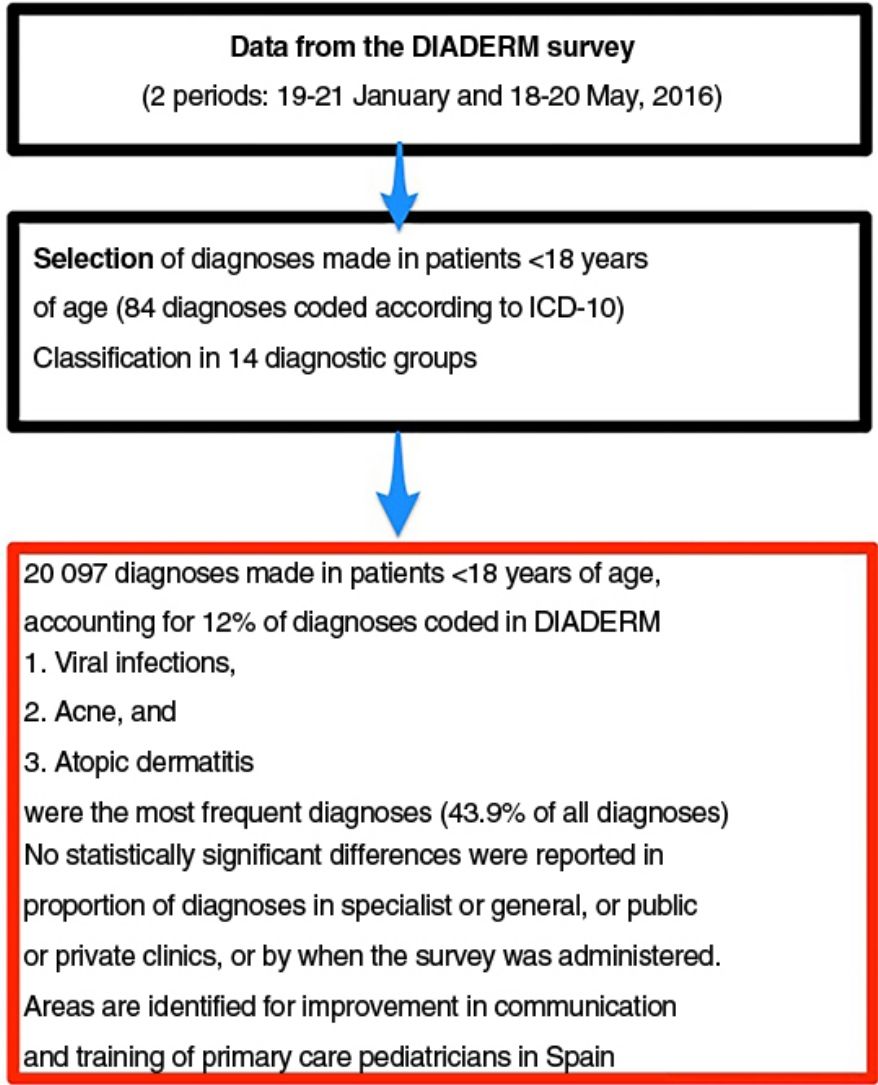

Material and methodsObservational cross-sectional study of diagnoses made in outpatient dermatology clinics during 2 data-collection periods in the anonymous DIADERM National Random Survey of dermatologists across Spain. All entries with an International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision code related to dermatology in the 2 periods (84 diagnoses) were collected for patients younger than 18 years and classified into 14 categories to facilitate analysis and comparison.

ResultsIn total, the search found 20 097 diagnoses made in patients younger than 18 years (12% of all coded diagnoses in the DIADERM database). Viral infections, acne, and atopic dermatitis were the most common, accounting for 43.9% of all diagnoses. No significant differences were observed in the proportions of diagnoses in the respective caseloads of specialist vs. general dermatology clinics or public vs. private clinics. Seasonal differences in diagnoses (January vs. May) were also nonsignificant.

ConclusionsPediatric care accounts for a significant proportion of the dermatologist's caseload in Spain. Our findings are useful for identifying opportunities for improving communication and training in pediatric primary care and for designing training focused on the optimal treatment of acne and pigmented lesions (with instruction on basic dermoscopy use) in these settings.

Los motivos de consulta de índole dermatológico son muy frecuentes en las consultas de pediatría de atención primaria, e igualmente muchos de los pacientes atendidos en consultas de dermatología son niños y adolescentes. A pesar de ello, faltan estudios sobre la prevalencia real de estas consultas y sus características.

Material y métodoEstudio observacional de corte transversal de 2 períodos de tiempo describiendo los diagnósticos realizados en consultas externas dermatológicas, obtenidos a través de la encuesta anónima DIADERM, realizada a una muestra aleatoria y representativa de dermatólogos. A partir de la codificación de diagnósticos CIE-10, se seleccionaron todos los diagnósticos codificados en los menores de 18 años (84 diagnósticos codificados en los 2 períodos), que se agruparon en 14 categorías diagnósticas relacionadas para facilitar su análisis y comparación.

ResultadosUn total de 20.097 diagnósticos fueron efectuados en pacientes menores de 18 años, lo que supone un 12% del total de los codificados en DIADERM. Las infecciones víricas, el acné y la dermatitis atópica fueron los diagnósticos más comunes (43,9% de todos los diagnósticos). No se observaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en la proporción de diagnósticos atendidos en las consultas monográficas frente a las generales, así como en los registrados en el ámbito público frente al privado. Tampoco las hubo en los diagnósticos en función de la época de la encuesta (enero y mayo).

ConclusionesLa atención a pacientes pediátricos por parte de dermatólogos en España supone una proporción significativa de la actividad habitual. Estos datos nos permiten descubrir áreas de mejora en la comunicación y la formación de los pediatras de atención primaria, como la necesidad del refuerzo de actividades formativas dirigidas al mejor tratamiento de acné y lesiones pigmentadas (y manejo básico de la dermatoscopia) en este ámbito asistencial.

It is estimated that between 6% and 30% of visits to pediatricians are due to dermatological disorders.1,2 Likewise, it is calculated that between 10% and 15% of patients attended in dermatology clinics are aged under 16 years.3–5

In childhood, the cutaneous manifestations of many diseases differ with respect to those of the same diseases in adulthood, and their management may also differ. Likewise, there are several dermatological afflictions that present mainly or exclusively in children. The variety of possible diagnoses and the need for specific management has led to the creation of clinics dedicated exclusively to pediatric dermatology.6,7 In Spain, pediatric dermatology is not recognized as a subspecialty, as is the case in other countries.7 This has led some authors to consider accredited courses to enable its recognition as such.8

Some patients referred from primary health care to dermatology clinics have a simple diagnosis that was made appropriately in the pediatric clinic, and the referral was made to optimize treatment (for example, in many cases of atopic dermatitis, vitiligo, psoriasis, infantile hemangiomas, skin infections such as viral warts or molluscum contagiosum, cystic lesions of different types...). However, other cases are referred to the dermatologist to confirm the nature of the disease or if a clear suspected diagnosis has not been achieved. In this case, in patients with rare diseases, for diagnostic confirmation, the dermatologist may need to order additional tests such as a histological analysis (prior surgery adapted to the pediatric population9) or request a genetic study. Many of these patients will finally be referred to specialist dermatology units for follow-up.10 The above notwithstanding, there are no multicenter studies conducted in Spain that have assessed the reasons for attending the clinic.

The objective of the DIADERM study was to analyze the diagnoses made in medical-surgical and venereological dermatology clinics of members of the Spanish Academy for Dermatology and Venerology (abbreviated in Spanish as AEDV) in Spain.5

With this study, we aimed to estimate the demand for outpatient care in patients of pediatric age, by dermatologists in Spain, based on coded diagnoses of activity made by the dermatologists themselves. Likewise, the aim was to analyze possible differences between these diagnoses by geographic area, source of referral, and the final destination by public and private sectors, as well as other factors.

Material and methodsThis was a cross-sectional observational study to determine the diagnoses made by dermatologists in 2 time periods (January 19-21 and May 18-20, 2016). These data were obtained via the anonymous DIADERM survey, administered to a random sample of dermatologists, stratified by AEDV section, and representative of dermatologists in Spain. The methods and characteristics of the survey (including the data collected and how the diagnoses were coded) have been described in detail in the first publication on the project.5

The variables previously collected in the study were included. For the specific analysis of dermatoses in patients of pediatric age, all diagnoses coded in those under 18 years of age were selected and these were grouped by related diagnostic category to facilitate analysis and comparison (Supplementary appendix 1). In order to approximate the frequency of diagnoses in a working week, the number of estimated diagnoses in a week of 5 working days was calculated.

The statistical analysis was performed taking into account the design used for sample collection, using the Stata survey module.11 The module takes into account obtaining standard errors for correlated data. Furthermore, a finite population correction factor was not required, taking the real number of dermatologists for each section of the AEDV, as this number was close to 1.

The study was classified as one not related to postapproval by the Spanish Agency for Medications and Health Products and approved by the Ethics Committee of the province of Granada, Spain (October 8, 2014).

ResultsDuring data collection for the DIADERM study, a total of 20 097 diagnoses were made in patients under 18 years of age, accounting for 12% of all coded diagnoses (in 2016).

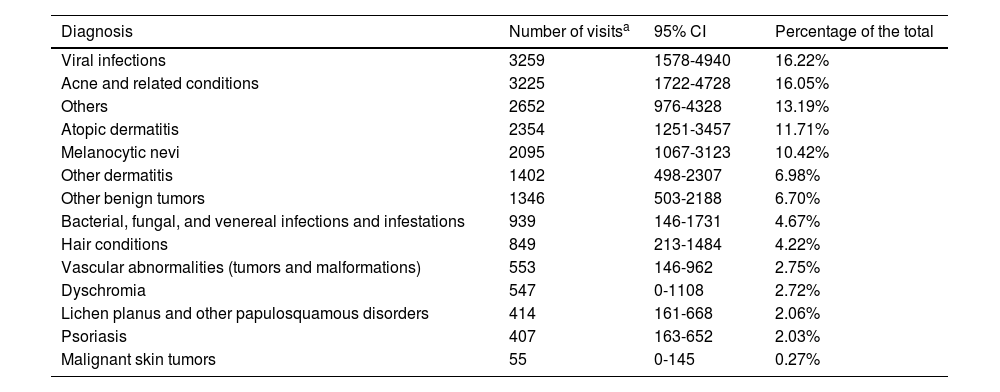

Table 1 shows the estimated frequency of diagnoses in a working week in patients under 18 years of age: viral infections, acne, and atopic dermatitis were, in descending order of frequency, the most common diagnoses, accounting for 43.9% of all diagnoses. The least frequent diagnoses were malignant skin tumors, coded under C44 (other malignant skin tumors) and C83 (nonfollicular lymphoma).

Estimated Frequency of Diagnoses in a Working Week in Patients Under 18 Years of Age Throughout Spain.

| Diagnosis | Number of visitsa | 95% CI | Percentage of the total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Viral infections | 3259 | 1578-4940 | 16.22% |

| Acne and related conditions | 3225 | 1722-4728 | 16.05% |

| Others | 2652 | 976-4328 | 13.19% |

| Atopic dermatitis | 2354 | 1251-3457 | 11.71% |

| Melanocytic nevi | 2095 | 1067-3123 | 10.42% |

| Other dermatitis | 1402 | 498-2307 | 6.98% |

| Other benign tumors | 1346 | 503-2188 | 6.70% |

| Bacterial, fungal, and venereal infections and infestations | 939 | 146-1731 | 4.67% |

| Hair conditions | 849 | 213-1484 | 4.22% |

| Vascular abnormalities (tumors and malformations) | 553 | 146-962 | 2.75% |

| Dyschromia | 547 | 0-1108 | 2.72% |

| Lichen planus and other papulosquamous disorders | 414 | 161-668 | 2.06% |

| Psoriasis | 407 | 163-652 | 2.03% |

| Malignant skin tumors | 55 | 0-145 | 0.27% |

Abbreviation: 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

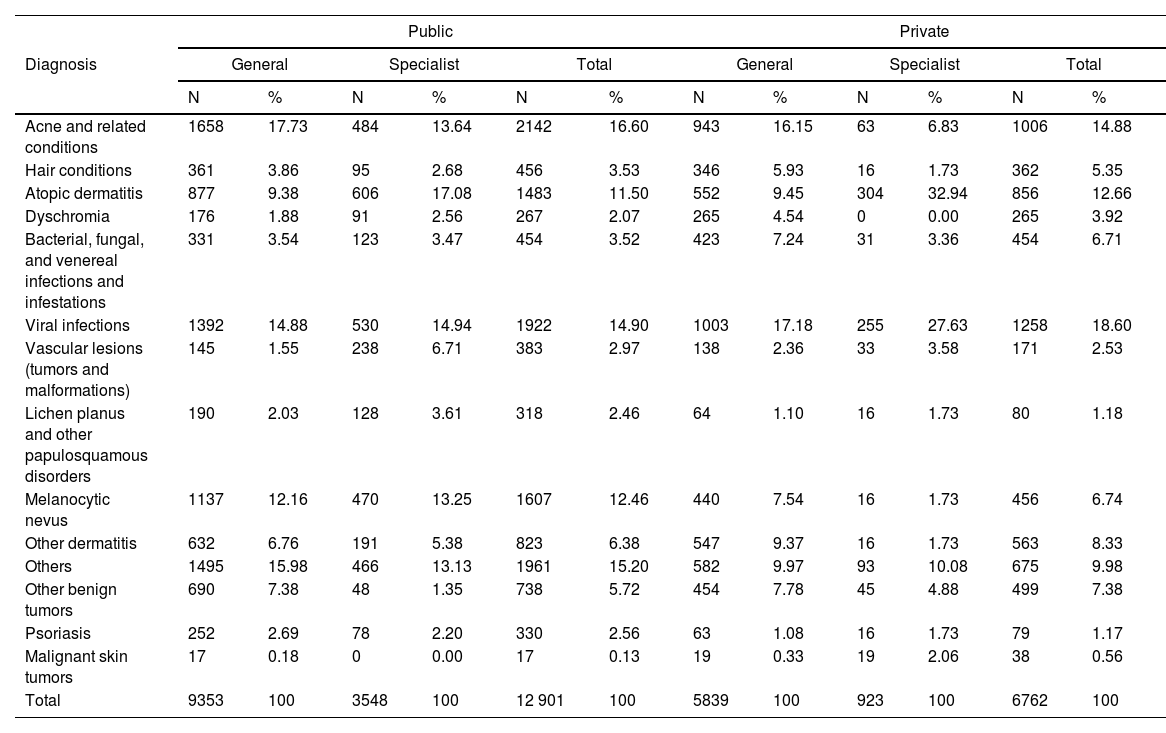

Table 2 shows the distribution of frequency of diagnoses by type of visit (primary health care or specialist, and in the public or private sector). There were no statistically significant differences between the public and private sectors. In the public sector, the 3 diagnostic groups reported most frequently were acne and related conditions (16.6%), viral infections (14.9%), and melanocytic nevi (12.5%). In the private sector, viral infections (18.6%), acne and related conditions (14.9%), and atopic dermatitis (12.7%) were the most frequently reported. Although numerically apparent in some cases, the differences in the proportion of diagnoses made in specialist clinics compared with primary health care, as well as those in public versus private sectors, were not significant.

Absolute and Relative Frequencies of Diagnoses by General or Specialist Clinics and by Public or Private Health Sector.

| Public | Private | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | General | Specialist | Total | General | Specialist | Total | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Acne and related conditions | 1658 | 17.73 | 484 | 13.64 | 2142 | 16.60 | 943 | 16.15 | 63 | 6.83 | 1006 | 14.88 |

| Hair conditions | 361 | 3.86 | 95 | 2.68 | 456 | 3.53 | 346 | 5.93 | 16 | 1.73 | 362 | 5.35 |

| Atopic dermatitis | 877 | 9.38 | 606 | 17.08 | 1483 | 11.50 | 552 | 9.45 | 304 | 32.94 | 856 | 12.66 |

| Dyschromia | 176 | 1.88 | 91 | 2.56 | 267 | 2.07 | 265 | 4.54 | 0 | 0.00 | 265 | 3.92 |

| Bacterial, fungal, and venereal infections and infestations | 331 | 3.54 | 123 | 3.47 | 454 | 3.52 | 423 | 7.24 | 31 | 3.36 | 454 | 6.71 |

| Viral infections | 1392 | 14.88 | 530 | 14.94 | 1922 | 14.90 | 1003 | 17.18 | 255 | 27.63 | 1258 | 18.60 |

| Vascular lesions (tumors and malformations) | 145 | 1.55 | 238 | 6.71 | 383 | 2.97 | 138 | 2.36 | 33 | 3.58 | 171 | 2.53 |

| Lichen planus and other papulosquamous disorders | 190 | 2.03 | 128 | 3.61 | 318 | 2.46 | 64 | 1.10 | 16 | 1.73 | 80 | 1.18 |

| Melanocytic nevus | 1137 | 12.16 | 470 | 13.25 | 1607 | 12.46 | 440 | 7.54 | 16 | 1.73 | 456 | 6.74 |

| Other dermatitis | 632 | 6.76 | 191 | 5.38 | 823 | 6.38 | 547 | 9.37 | 16 | 1.73 | 563 | 8.33 |

| Others | 1495 | 15.98 | 466 | 13.13 | 1961 | 15.20 | 582 | 9.97 | 93 | 10.08 | 675 | 9.98 |

| Other benign tumors | 690 | 7.38 | 48 | 1.35 | 738 | 5.72 | 454 | 7.78 | 45 | 4.88 | 499 | 7.38 |

| Psoriasis | 252 | 2.69 | 78 | 2.20 | 330 | 2.56 | 63 | 1.08 | 16 | 1.73 | 79 | 1.17 |

| Malignant skin tumors | 17 | 0.18 | 0 | 0.00 | 17 | 0.13 | 19 | 0.33 | 19 | 2.06 | 38 | 0.56 |

| Total | 9353 | 100 | 3548 | 100 | 12 901 | 100 | 5839 | 100 | 923 | 100 | 6762 | 100 |

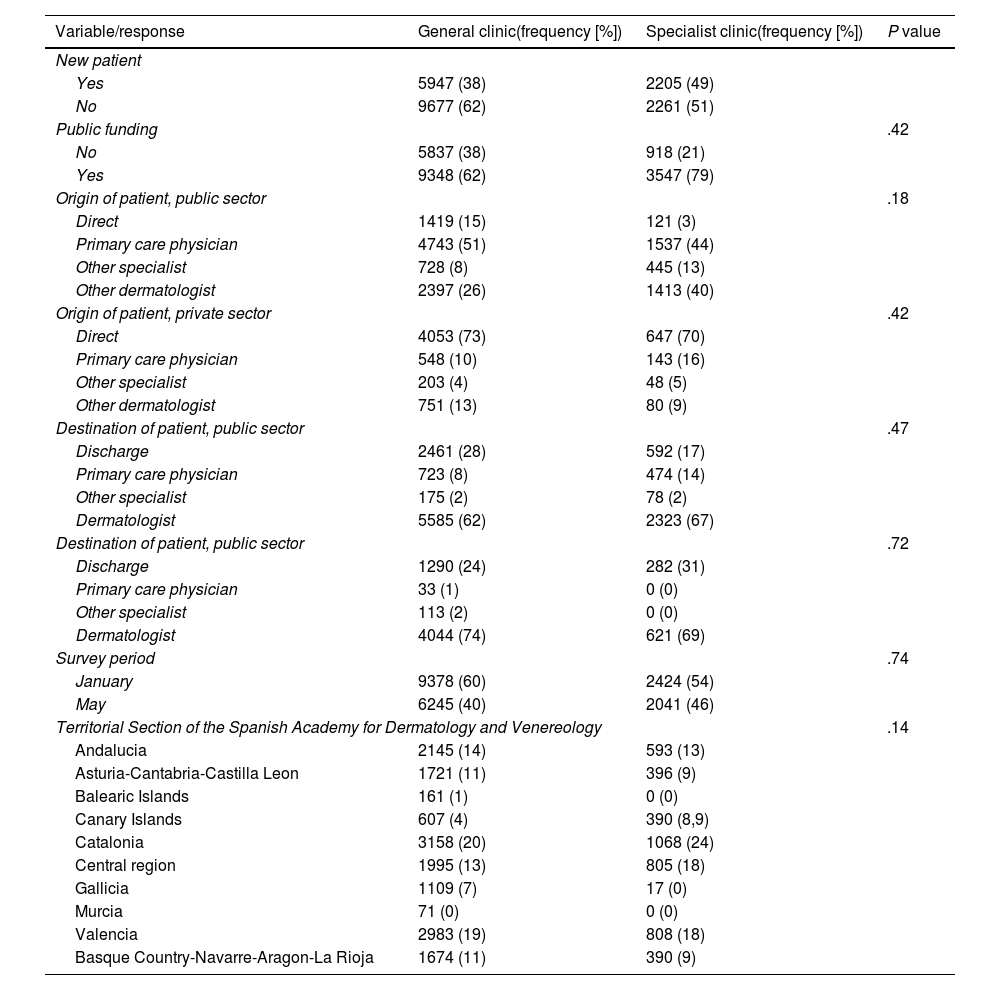

Likewise, no statistically significant differences were observed between primary health care and specialist clinics (Table 3) in terms of factors such as index of new patients/patients in follow-up, reimbursement, origin and destination of the patients, and phase of administration of the survey (January or May 2016).

Differences Between General and Specialist Clinics.

| Variable/response | General clinic(frequency [%]) | Specialist clinic(frequency [%]) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| New patient | |||

| Yes | 5947 (38) | 2205 (49) | |

| No | 9677 (62) | 2261 (51) | |

| Public funding | .42 | ||

| No | 5837 (38) | 918 (21) | |

| Yes | 9348 (62) | 3547 (79) | |

| Origin of patient, public sector | .18 | ||

| Direct | 1419 (15) | 121 (3) | |

| Primary care physician | 4743 (51) | 1537 (44) | |

| Other specialist | 728 (8) | 445 (13) | |

| Other dermatologist | 2397 (26) | 1413 (40) | |

| Origin of patient, private sector | .42 | ||

| Direct | 4053 (73) | 647 (70) | |

| Primary care physician | 548 (10) | 143 (16) | |

| Other specialist | 203 (4) | 48 (5) | |

| Other dermatologist | 751 (13) | 80 (9) | |

| Destination of patient, public sector | .47 | ||

| Discharge | 2461 (28) | 592 (17) | |

| Primary care physician | 723 (8) | 474 (14) | |

| Other specialist | 175 (2) | 78 (2) | |

| Dermatologist | 5585 (62) | 2323 (67) | |

| Destination of patient, public sector | .72 | ||

| Discharge | 1290 (24) | 282 (31) | |

| Primary care physician | 33 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Other specialist | 113 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| Dermatologist | 4044 (74) | 621 (69) | |

| Survey period | .74 | ||

| January | 9378 (60) | 2424 (54) | |

| May | 6245 (40) | 2041 (46) | |

| Territorial Section of the Spanish Academy for Dermatology and Venereology | .14 | ||

| Andalucia | 2145 (14) | 593 (13) | |

| Asturia-Cantabria-Castilla Leon | 1721 (11) | 396 (9) | |

| Balearic Islands | 161 (1) | 0 (0) | |

| Canary Islands | 607 (4) | 390 (8,9) | |

| Catalonia | 3158 (20) | 1068 (24) | |

| Central region | 1995 (13) | 805 (18) | |

| Gallicia | 1109 (7) | 17 (0) | |

| Murcia | 71 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Valencia | 2983 (19) | 808 (18) | |

| Basque Country-Navarre-Aragon-La Rioja | 1674 (11) | 390 (9) | |

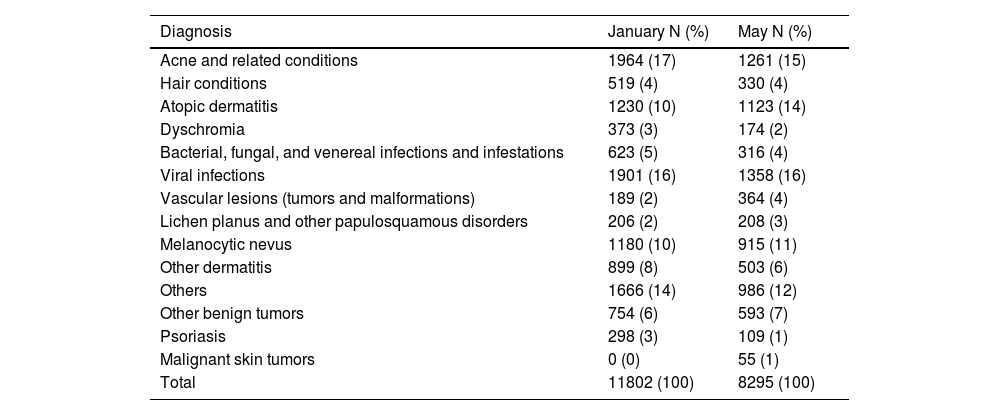

Finally, there were also no significant differences (P=.31) in diagnoses coded according to season of the year (survey in January or May), recorded in Table 4.

Estimated Frequencies of Diagnoses by Season of the Year (Survey Phase of January or May).

| Diagnosis | January N (%) | May N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Acne and related conditions | 1964 (17) | 1261 (15) |

| Hair conditions | 519 (4) | 330 (4) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 1230 (10) | 1123 (14) |

| Dyschromia | 373 (3) | 174 (2) |

| Bacterial, fungal, and venereal infections and infestations | 623 (5) | 316 (4) |

| Viral infections | 1901 (16) | 1358 (16) |

| Vascular lesions (tumors and malformations) | 189 (2) | 364 (4) |

| Lichen planus and other papulosquamous disorders | 206 (2) | 208 (3) |

| Melanocytic nevus | 1180 (10) | 915 (11) |

| Other dermatitis | 899 (8) | 503 (6) |

| Others | 1666 (14) | 986 (12) |

| Other benign tumors | 754 (6) | 593 (7) |

| Psoriasis | 298 (3) | 109 (1) |

| Malignant skin tumors | 0 (0) | 55 (1) |

| Total | 11802 (100) | 8295 (100) |

No statistically significant differences in the distribution of diagnoses by season; P value=.31.

The present study reviewed data related to pediatric patients from the DIADERM survey. In 2016, these patients accounted for 12% of the case load of specialists in medical-surgical dermatology and venereology in Spain. The most frequent diagnoses in this population group were viral infections, acne and related disorders, and atopic dermatitis.

The figure of 12% of pediatric patients in the dermatology clinics is lower than that reported in the series published by Taberner et al.12 in 2010 (17.4%), but consistent with previous studies such as that of Casanova et al.3 in 2008 (12.1%) and very close to that reported by Goh and Akarapanth4 in 1994 (12.4%), although in the aforementioned 3 studies, the cutoff age for considering a patient to be of pediatric age was 16 years.

The findings of previous studies show how the frequencies of diagnoses vary, and so they are not fully consistent with the case profile observed in our study. Specialist public sector clinics included in the DIADERM survey did coincide in the 3 most frequent diagnoses with the most common ones in 1984 in outpatient pediatric clinics in a center in the United States13: infectious dermatoses, atopic dermatitis, and acne, which could indicate a closer collaboration between pediatricians and pediatric dermatology in some cases (or that it is easier to directly access the dermatologist in the private sector). A review published in Spain in 200514 reported that the most frequent dermatoses in primary care were infections (with bacteria as the most common pathogens), followed by nappy rash (currently, thanks to the new diaper designs, the incidence of this latter condition is clearly lower), and atopic conditions (based on data published in 198515). In turn, the most frequent conditions reported in pediatric dermatology clinics were infections (most frequently due to fungi, whose incidence has clearly decreased due to better hygiene, better veterinary control...), followed by atopic dermatitis, and acne vulgaris (according to data published in 198316). The most frequent pediatric dermatoses in dermatology emergency rooms of a tertiary hospital in Spain according to a study from 2004 included infections and eczemas, although insect bites/prurigo were reported as the third most frequent reason for the visit.17

In a more detailed examination of the data presented, we highlight those presented in Table 1, which emphasize the importance of training for primary health care. This could avoid referral of cases for assessment by a dermatologist. Regarding what is reflected in Table 2, we highlight the following more frequent diagnoses in public specialist clinics: acne (we believe partly because of economic considerations, that is, isotretinoin prescriptions are covered, as well as the blood workups) and vascular anomalies (also because of economic reasons, although it could also be related to the greater ease of access to multidisciplinary committees, requests for specific diagnostic tests, and access to advanced treatments). Conversely, atopic dermatitis, viral infections, and other types of dermatitis are proportionally more frequent in the private sector (this may be because it is easier to get a direct appointment and/or an earlier appointment). The difference in proportion of diagnoses of melanocytic nevi in the public sector compared with the private one was noteworthy. This could be the result of a lack of urgency, with less concern about waiting for an appointment in the public health system.

In the case of specialist clinics, the study by Torrelo and Zambrano2 in 2002 in the pediatric dermatology department of the Hospital Universitario Niño Jesús, Madrid, Spain, describing the frequencies of diagnoses, found the most frequent were, in descending order, eczema, infectious dermatoses, and nevi. We believe that the data from specialist clinics in the DIADERM study do not completely coincide with the pediatric dermatology department of that hospital because the classification in the survey as such was not strictly limited to pediatric dermatology, but rather to any specialist dermatology visit. This fact may explain the relatively high number of malignant tumors among those diagnosed, more prevalent in other nonpediatric specialist clinics. On the other hand, in our case, infectious dermatoses have been divided into several blocks, viral and others, and eczemas into atopic dermatitis and other dermatitis (if these were combined, the results would be rather similar). The main difference is in acne, which is currently a very common reason for visits in Spain. The most recent study describing the types of visit in pediatric dermatology is a Greek series, whose most frequent diagnoses were eczema, viral infections, and pigmentary disorders (considered separately from melanocytic nevi, which were the fourth most frequent diagnosis).10 Comparing our data with those of that study, we find that acne accounted for many more cases in our study. This could be because of the wide age range included in our study, as well as cultural factors in Greece (with an overall lower demand for care) and even factors such as genetic ones, diet, or lifestyle, which could favor a lower prevalence of acne in that country.

Likewise, that fact that there were no statistically significant differences in our data on general visits compared with visits to specialists (even though trends were observed) could be due to the limited number of cases or to the general observation that the difference between specialist clinics and general ones is more a question of severity.

Although more diagnoses were reported in January than in May 2016 during the data collection phase of DIADERM, we have not been able to observe significant differences in the relative distribution of dermatoses identified in these 2 periods. The only previous study we encountered that analyzed the frequency of dermatoses by month of year likewise did not find any clear differences.13

The study is subject to some limitations, such as the fact that pediatric population is defined as under 18 years of age (when in some studies, the cutoff used is 16 years or under) and the impossibility of identifying specialist pediatric dermatology clinics (the classification of specialist clinic in the DIADERM study did not refer solely to specialist pediatric dermatology clinics). Likewise, we were unable to analyze the data by more specific age ranges or by sex. In addition, the 2 data collection periods (January and May) do not allow ready delimitation of the seasons (for example, in summer it might be expected that the incidence of impetigo is higher while that of atopic dermatitis is lower), which in turn could be influenced by the waiting list. Finally, it is of note that the data collected in the study are from 2016 and so it is possible that the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic means that the data from the DIADERM survey needs to be updated to reflect the postpandemic situation.

Nevertheless, the study has its strengths, such as the methodology used, representative of the activity of dermatologists in Spain, and the large sample size that lends precision to the results.

ConclusionsCare of patients by dermatologists in Spain accounts for a significant part of their normal activity, and knowledge of their prevalence and distribution is very important for considering strategies for improvement. Infectious dermatoses, atopic dermatitis, and acne are the most frequently reported diagnoses in patients under 18 years of age.

We believe that the findings described can point to areas for improvement in communication and training of primary care pediatricians, and the need to reinforce training activities aimed at improving the management of acne and pigmented lesions in primary care. We believe new studies are needed specifically focused on pediatric patients to obtain more information.

FundingThe DIADERM study was instigated by the Fundación Piel Sana (Health Skin Foundation) of the AEDV, and received financial support from Novartis. The pharmaceutical company did not participate in data collection, data analysis, or interpretation of the results.

AuthorshipMartin-Gorgojo and J. del Boz contributed equally as primary authors.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version available at doi:10.1016/j.ad.2023.09.009.