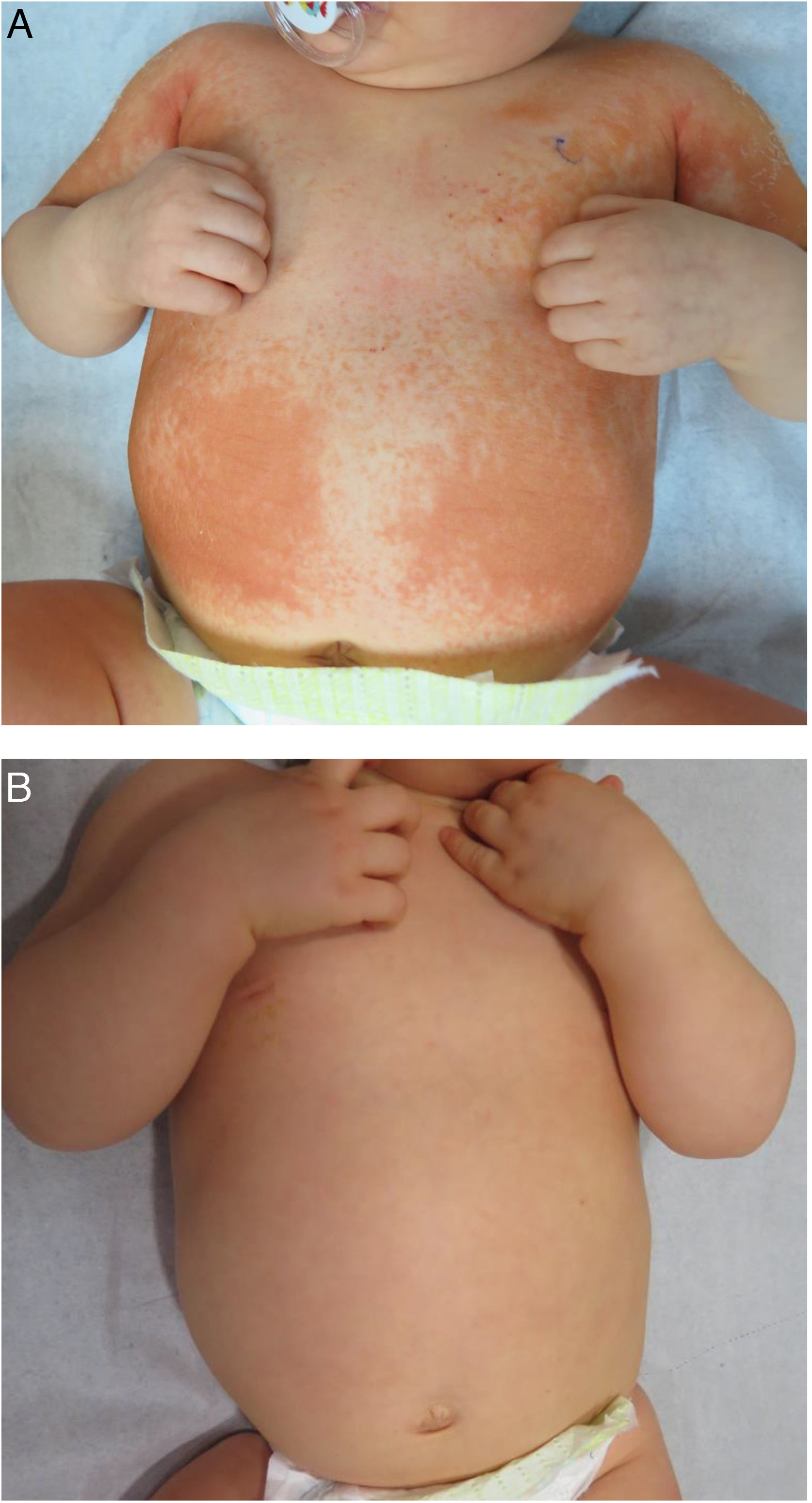

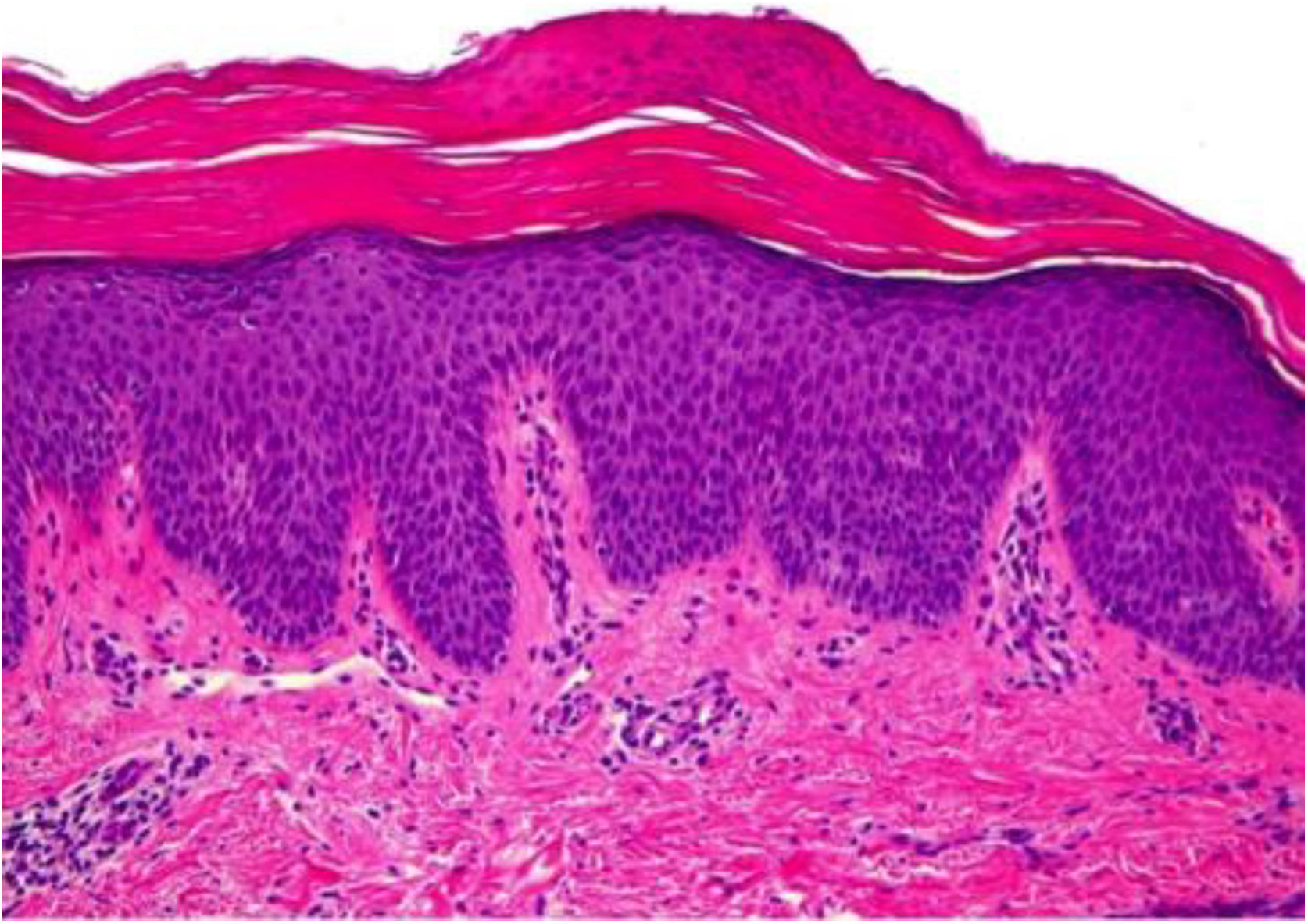

A 9-month-old boy was seen for a localized skin rash on the abdomen and extremities that had spread rapidly over the preceding 2 months. The patient had no other associated symptoms. His clinical history included multiple episodes of pyelectasis that had been treated with prophylactic antibiotics (cefadroxil) up to 5 months of age. Before the skin lesions appeared, the patient had undergone antibiotic and corticosteroid treatment for multiple viral and bacterial infections of the upper respiratory tract. Physical examination revealed confluent salmon-pink papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities (Fig. 1A), with islands of healthy skin on both legs. Biopsies of the lesions showed acanthosis, hypergranulosis, orthokeratosis, parakeratosis, and mild superficial infiltrate, findings consistent with pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) (Fig. 2). The patient was treated for 1 month with topical 0.05% triamcinolone acetonide cream, which resulted in complete resolution of the lesions (Fig. 1B). Due to the patient’s clinical history of recent respiratory infections, the early resolution of the skin lesions, and the histological findings, a diagnosis of acute postinfectious PRP was proposed.

PRP is a skin disease that rarely affects children. In 1980, Griffiths proposed a classification system that divided PRP into 5 categories according to clinical and epidemiological features and clinical course. Variants that occur in children include classical juvenile (type III), circumscribed juvenile (type IV), and atypical juvenile (type V) PRP.1 In 1983, Larregue described a new variant called postinfectious PRP, based on a case series of children aged over 1 year with a history of one or more recent respiratory infections. These patients presented skin lesions that resembled those of juvenile classic PRP, but with acute onset, a good prognosis, and a low tendency to recur.2 While skin lesions in postinfectious PRP may resemble other superantigen-mediated dermatoses, their histology and treatment are distinct.

Few studies have investigated treatment efficacy in children with PRP. In patients with types III and IV, the best results have been achieved with systemic retinoids.3,4 The use of oral vitamin A is controversial, as a good response has been observed only in a few patients.5 Ferrándiz-Pulido et al published a series of 4 children diagnosed with postinfectious PRP, 3 of whom were treated with topical corticosteroids. Only one patient responded favorably to the 5-week treatment. The others required acitretin treatment to achieve a clinical response. The fourth patient underwent a 3-week course of topical emollients and salicylic acid, with a complete response.2

In our patient, treatment with topical emollients and triamcinolone acetonide proved effective, although we cannot rule out the possibility of spontaneous resolution given the potential postinfectious etiology of the condition.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Zegpi-Trueba MS, Navajas-Galimany L, González S, Ramírez-Cornejo C. Pitiriasis rubra pilaris aguda postinfecciosa: gran respuesta a emolientes y a corticosteroides tópicos. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021;112:667–668.