The incidence of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) to cosmetics in the general population is rising with the increasing use of cosmetic products and their proliferation and diversification. The aims of this study were to determine the prevalence of ACD to cosmetics in our setting, analyze changes over time, describe the clinical and epidemiological features of this allergic reaction, and identify the allergens and cosmetics involved. We performed a prospective study at the skin allergy unit in Hospital General Universitario de Valencia in Spain between 2005 and 2013 and compared our findings with data collected retrospectively for the period 1996 to 2004. The 5419 patients who underwent patch testing during these 2 periods were included in the study. The mean prevalence of ACD to cosmetics increased from 9.8% in the first period (1996-2004) to 13.9% in the second period (2005-2013). A significant correlation was found between ACD to cosmetics and female sex but not atopy. Kathon CG (blend of methylchloroisothiazolinone and methylisothiazolinone), fragrances, and paraphenylenediamine were the most common causes of ACD to cosmetics during both study periods, and acrylates and sunscreens were identified as emerging allergens during the second period.

La dermatitis alérgica de contacto (DAC) a cosméticos es una dolencia con una incidencia creciente en la población, paralelamente a la generalización del uso de cosméticos en la sociedad, así como a su proliferación y diversificación.

El objetivo del estudio es determinar la prevalencia de DAC a cosméticos en nuestro medio, analizar su evolución temporal y sus características clínico-epidemiológicas, así como definir los alérgenos y los cosméticos implicados.

Se ha realizado un estudio prospectivo durante los años 2005-2013 en la Unidad de Alergia Cutánea del Hospital General Universitario de Valencia, y se ha comparado de forma retrospectiva con el periodo previo de 1996-2004.

Se ha incluido a 5.419 pacientes estudiados con pruebas epicutáneas durante el periodo total del estudio. La prevalencia media de DAC a cosméticos ha aumentado de 9,8% en el periodo 1996-2004 a 13,9% en el periodo 2005-2013. La DAC a cosméticos se ha correlacionado con el sexo femenino, pero no con la atopia. El kathon CG (mezcla de metilcloroisotiazolinona y metilisotiazolinona), las fragancias y la parafenilendiamina (PPDA) se han mantenido como las causas más frecuentes, aunque en los últimos años los acrilatos y los filtros solares han sido alérgenos emergentes.

In today's society, physical beauty is more strongly pursued than ever and is considered synonymous with success and happiness. The associated social and cultural pressure transmitted and boosted by the media and advertising has led to mass—and even pathological—consumption of multiple beauty products and services. Cosmetics are the most important products on the beauty market, and their growth and diversification seem unstoppable.1 However, despite being subject to strict legislation,2 cosmetics are not free from adverse reactions.

Few data are available on the real incidence of adverse reactions to cosmetics, which, although estimated at 12% in the general population, has reached 47% in patients referred for patch testing.3 Adverse reactions to cosmetics most commonly manifest as contact dermatitis, with irritant contact dermatitis the most frequent form. However, allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is of particular interest because of the severity of the symptoms it produces, the need to identify the allergen before the condition can be cured, and the risk of cross-reactions.4

The prevalence of ACD to cosmetics in patients referred for patch testing was traditionally reported to be 2%-4%, although more recent studies point to a progressive increase in these values.5

The objectives of the present study were to analyze the prevalence of ACD to cosmetics and the progress of the condition over time, describe the clinical and epidemiological features of the reaction, and identify the allergens and cosmetics involved.

Material and MethodsWe included all patients who underwent patch testing at the Skin Allergy Unit of Hospital General Universitario de Valencia, Valencia, Spain between January 1996 and December 2013. We performed a prospective study during 2005-2013, the results of which were compared with those from the preceding period (1996-2004). We recorded epidemiological variables (sex, age, profession, atopy), clinical variables (skin lesions, duration, location, initial diagnosis), and variables associated with the examinations (patch testing, positive patch test results, relevance, cosmetic products, and source of sensitization). All patients underwent patch testing with the standard series of the Spanish Contact Dermatitis and Skin Allergy Research Group (Martí Tor). Depending on the findings from the clinical history, additional testing was performed with specific allergen series (Martí Tor) or with the patient's own products. Readings were taken at 48 and 96hours following the recommendations of the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group.

A descriptive statistical analysis was performed to determine the general prevalence trends and sociodemographic profiles of patients with ACD to cosmetics. Using contingency tables and significance testing, we also identified the epidemiological and diagnostic characteristics associated with the development of ACD to cosmetics.

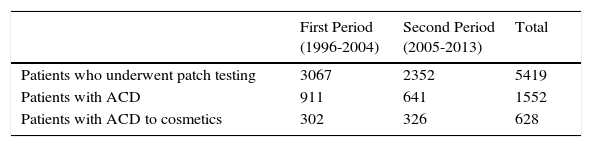

ResultsThe study population comprised 5419 patients. Table 1 shows data for all the patients who underwent patch testing, patients with ACD, and patients with ACD to cosmetics.

Total Number of Patients Included in the Study, Total Number of Patients with ACD, and Total Number of Patients With ACD to Cosmetics.

| First Period (1996-2004) | Second Period (2005-2013) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients who underwent patch testing | 3067 | 2352 | 5419 |

| Patients with ACD | 911 | 641 | 1552 |

| Patients with ACD to cosmetics | 302 | 326 | 628 |

Abbreviation: ADC, allergic contact dermatitis.

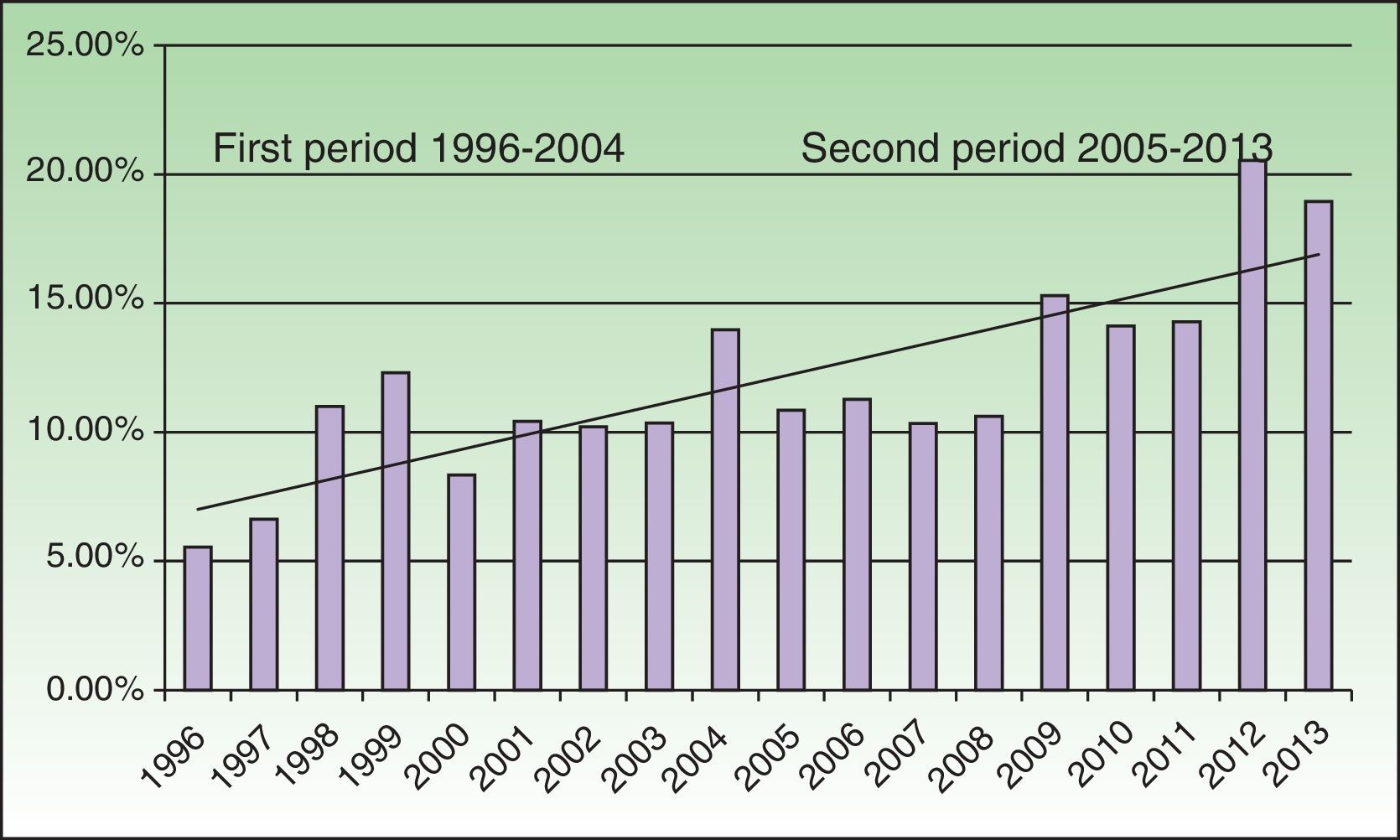

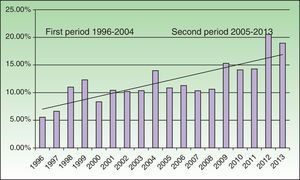

The mean prevalence of ACD to cosmetics was 11.6% in patients referred for patch testing. This increased from 9.8% during the first period to 13.9% in the second period, with a peak value of 18.9% in 2013 (Fig. 1). The frequency of cosmetics as the cause of ACD increased from 33.1% during the first period to 50.8% during the second period.

As for the epidemiologic profile, 75.9% of patients were women. Female sex was significantly associated with development of ACD to cosmetics. Men scarcely accounted for one-quarter of cases, although a slight increase was observed in the second period. The mean age of patients with ACD to cosmetics was 41.8 years. Atopy was also recorded in 11.7% of patients. The result of the chi-square test (P<.001) confirmed the inverse relationship between ACD to cosmetics and atopy: only 4.5% of all atopic patients were allergic to cosmetics, whereas 14.7% of those with no history of atopy had ACD to cosmetics. The occupations most closely associated with ACD to cosmetics were homemaker (28.8%), student (10.7%), and administrative worker (10.2%). Grouping by academic qualifications revealed a statistically significant association between low-grade professional qualifications and ACD to cosmetics (P<.001, chi-square).

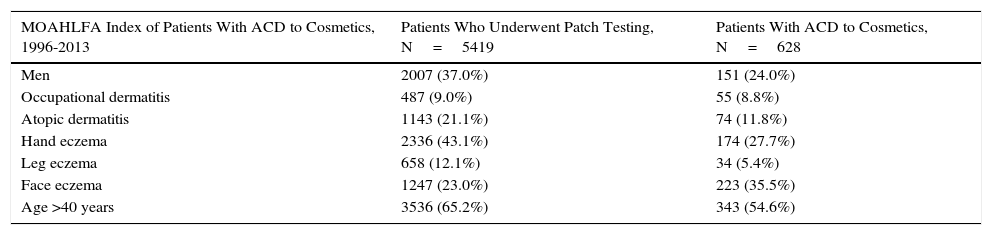

The mean time from onset of symptoms (eczema in 99% of cases) to diagnosis of ACD to cosmetics was 17.2 months. The most common initial diagnosis was ACD (89.9%). The most frequent site of dermatitis was the face (35.5%), followed by the hands (32.8%) and the neck (21.5%). The MOAHLFA index of patients with ACD to cosmetics is shown in Table 2.

MOAHLFA Indexa

| MOAHLFA Index of Patients With ACD to Cosmetics, 1996-2013 | Patients Who Underwent Patch Testing, N=5419 | Patients With ACD to Cosmetics, N=628 |

|---|---|---|

| Men | 2007 (37.0%) | 151 (24.0%) |

| Occupational dermatitis | 487 (9.0%) | 55 (8.8%) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 1143 (21.1%) | 74 (11.8%) |

| Hand eczema | 2336 (43.1%) | 174 (27.7%) |

| Leg eczema | 658 (12.1%) | 34 (5.4%) |

| Face eczema | 1247 (23.0%) | 223 (35.5%) |

| Age >40 years | 3536 (65.2%) | 343 (54.6%) |

Abbreviation: ACD, allergic contact dermatitis.

The definitive diagnosis was ACD in 608 patients (96.8%) and photoallergic contact dermatitis in 20 patients (3.2%).

The condition presented mainly as nonoccupational (consumer) dermatitis (91.2%), whereas in 55 cases (8.8%) the patient became sensitized in the workplace. Of note, the number of cases of occupational dermatitis detected during the second period was almost double that of the first period (11% vs 6%). This increase was statistically significant. Hairdressers were the profession most frequently affected in the first period of the study (paraphenylenediamine [PPDA]) and beauticians in the second (acrylates).

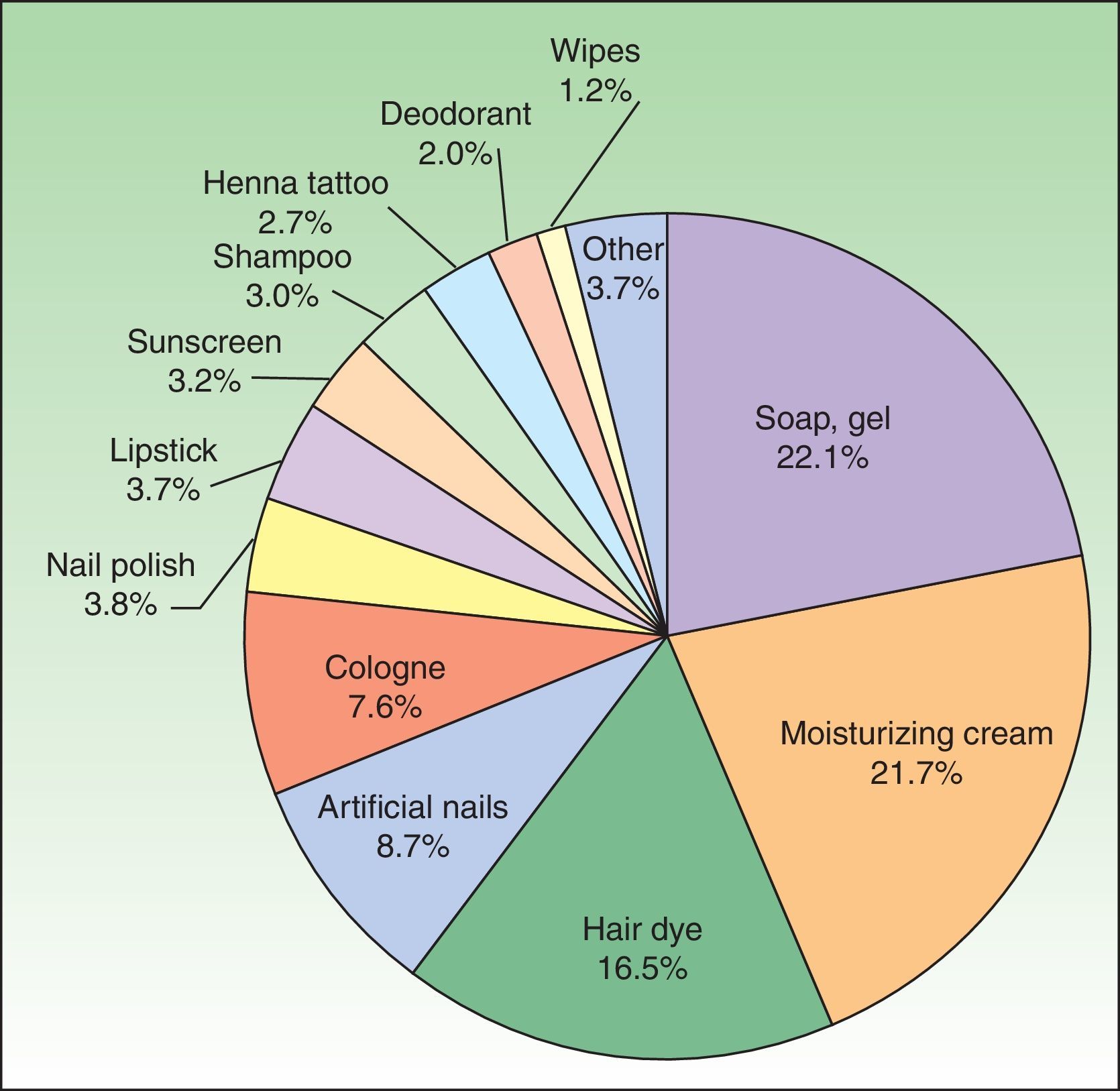

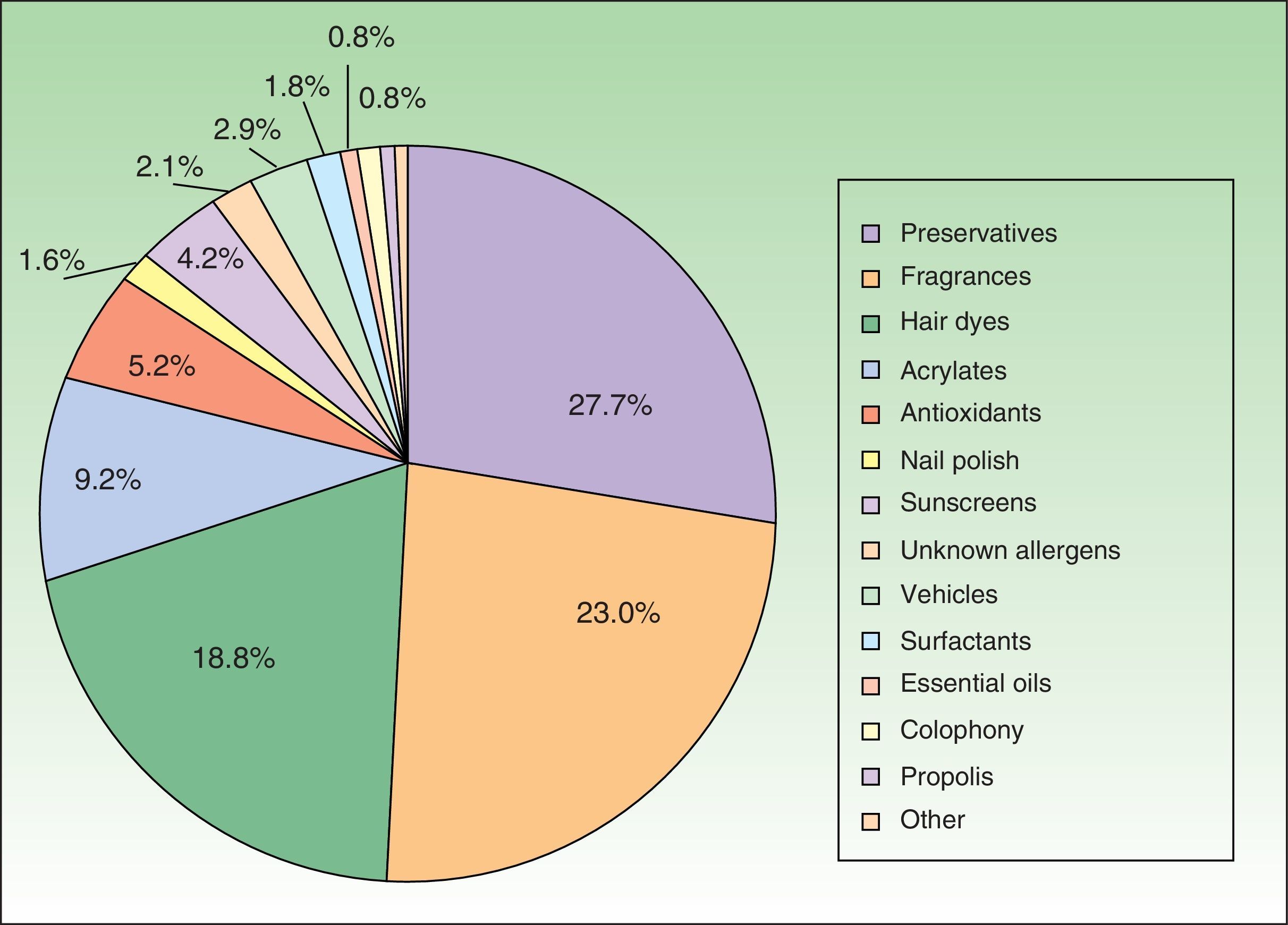

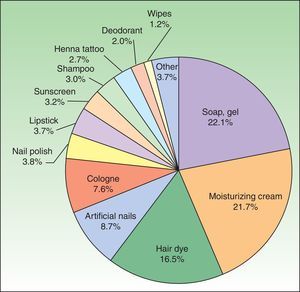

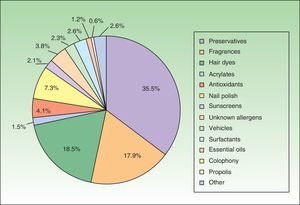

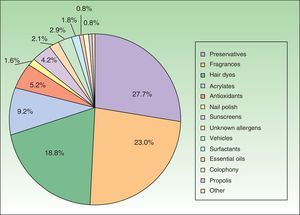

The products most frequently associated with ACD are shown in Fig. 2.

We analyzed a total of 1115 positive patches. The mean number of positive patches per patient increased from 1.5 in the first period to 2.0 in the second. More than half of the positive cases (51.8%) were diagnosed using the standard series. The additional series that yielded the highest number of positive results were fragrances, acrylates, and preservatives. Relevance was considered present in most cases (99%). Cases of unknown relevance (fragrances) or past relevance (PPDA) were exceptional.

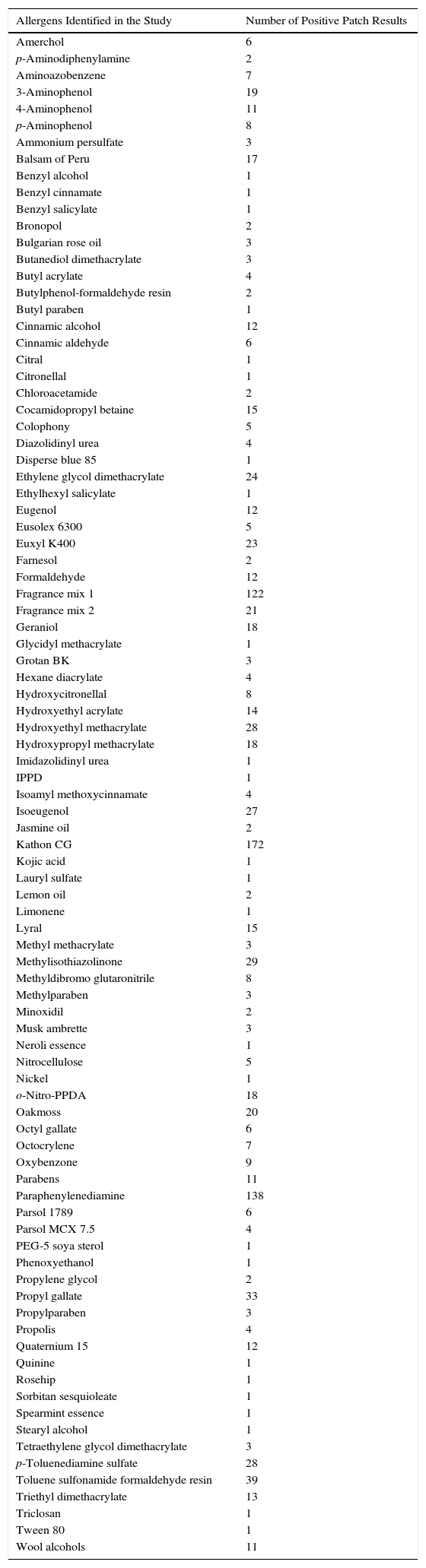

We identified 92 allergens causing ACD to cosmetics. The 20 most common positive allergens are shown in Table 3. The most common allergens are shown by category in Figures 3–5. Of note, the allergen remained unidentified in as few as 3.3% of cases, and the only test that made it possible to establish a diagnosis was patch testing with the patient's own products.

Positive Allergens in Patients Diagnosed With Allergic Contact Dermatitis to Cosmetics.

| Allergens Identified in the Study | Number of Positive Patch Results |

|---|---|

| Amerchol | 6 |

| p-Aminodiphenylamine | 2 |

| Aminoazobenzene | 7 |

| 3-Aminophenol | 19 |

| 4-Aminophenol | 11 |

| p-Aminophenol | 8 |

| Ammonium persulfate | 3 |

| Balsam of Peru | 17 |

| Benzyl alcohol | 1 |

| Benzyl cinnamate | 1 |

| Benzyl salicylate | 1 |

| Bronopol | 2 |

| Bulgarian rose oil | 3 |

| Butanediol dimethacrylate | 3 |

| Butyl acrylate | 4 |

| Butylphenol-formaldehyde resin | 2 |

| Butyl paraben | 1 |

| Cinnamic alcohol | 12 |

| Cinnamic aldehyde | 6 |

| Citral | 1 |

| Citronellal | 1 |

| Chloroacetamide | 2 |

| Cocamidopropyl betaine | 15 |

| Colophony | 5 |

| Diazolidinyl urea | 4 |

| Disperse blue 85 | 1 |

| Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate | 24 |

| Ethylhexyl salicylate | 1 |

| Eugenol | 12 |

| Eusolex 6300 | 5 |

| Euxyl K400 | 23 |

| Farnesol | 2 |

| Formaldehyde | 12 |

| Fragrance mix 1 | 122 |

| Fragrance mix 2 | 21 |

| Geraniol | 18 |

| Glycidyl methacrylate | 1 |

| Grotan BK | 3 |

| Hexane diacrylate | 4 |

| Hydroxycitronellal | 8 |

| Hydroxyethyl acrylate | 14 |

| Hydroxyethyl methacrylate | 28 |

| Hydroxypropyl methacrylate | 18 |

| Imidazolidinyl urea | 1 |

| IPPD | 1 |

| Isoamyl methoxycinnamate | 4 |

| Isoeugenol | 27 |

| Jasmine oil | 2 |

| Kathon CG | 172 |

| Kojic acid | 1 |

| Lauryl sulfate | 1 |

| Lemon oil | 2 |

| Limonene | 1 |

| Lyral | 15 |

| Methyl methacrylate | 3 |

| Methylisothiazolinone | 29 |

| Methyldibromo glutaronitrile | 8 |

| Methylparaben | 3 |

| Minoxidil | 2 |

| Musk ambrette | 3 |

| Neroli essence | 1 |

| Nitrocellulose | 5 |

| Nickel | 1 |

| o-Nitro-PPDA | 18 |

| Oakmoss | 20 |

| Octyl gallate | 6 |

| Octocrylene | 7 |

| Oxybenzone | 9 |

| Parabens | 11 |

| Paraphenylenediamine | 138 |

| Parsol 1789 | 6 |

| Parsol MCX 7.5 | 4 |

| PEG-5 soya sterol | 1 |

| Phenoxyethanol | 1 |

| Propylene glycol | 2 |

| Propyl gallate | 33 |

| Propylparaben | 3 |

| Propolis | 4 |

| Quaternium 15 | 12 |

| Quinine | 1 |

| Rosehip | 1 |

| Sorbitan sesquioleate | 1 |

| Spearmint essence | 1 |

| Stearyl alcohol | 1 |

| Tetraethylene glycol dimethacrylate | 3 |

| p-Toluenediamine sulfate | 28 |

| Toluene sulfonamide formaldehyde resin | 39 |

| Triethyl dimethacrylate | 13 |

| Triclosan | 1 |

| Tween 80 | 1 |

| Wool alcohols | 11 |

Abbreviation: IPPD; N-isopropyl N-phenyl-4-phenylenediamine

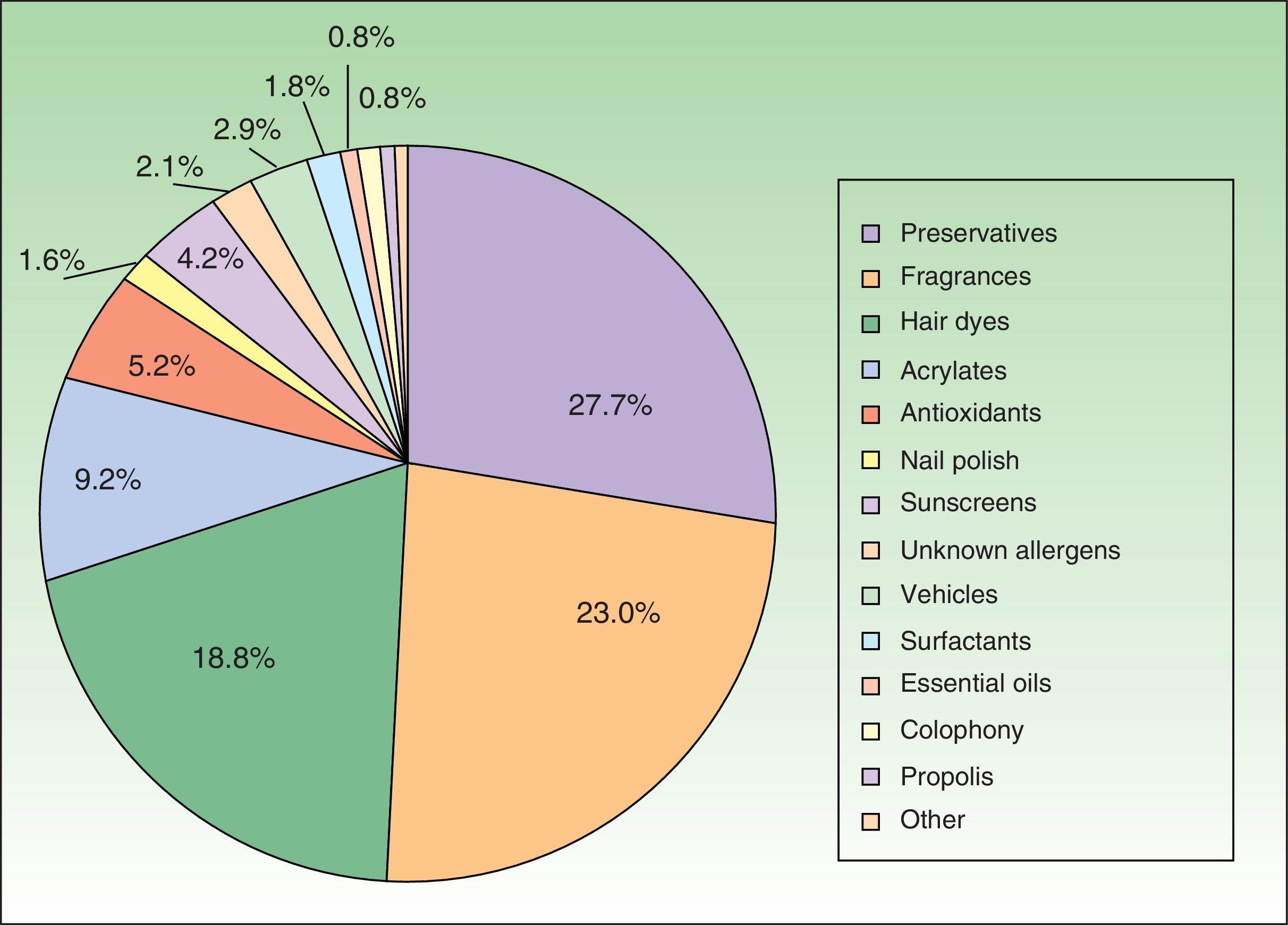

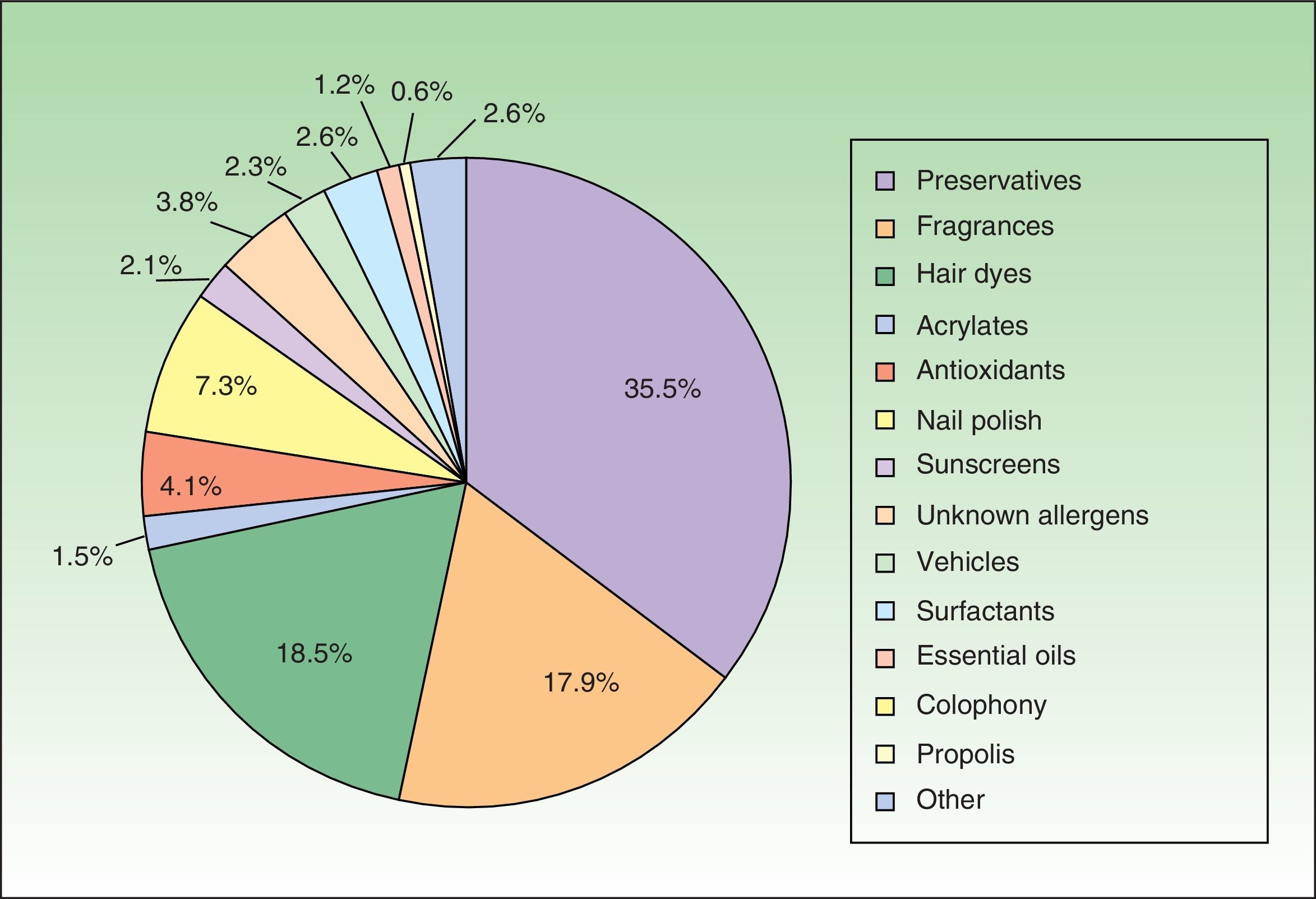

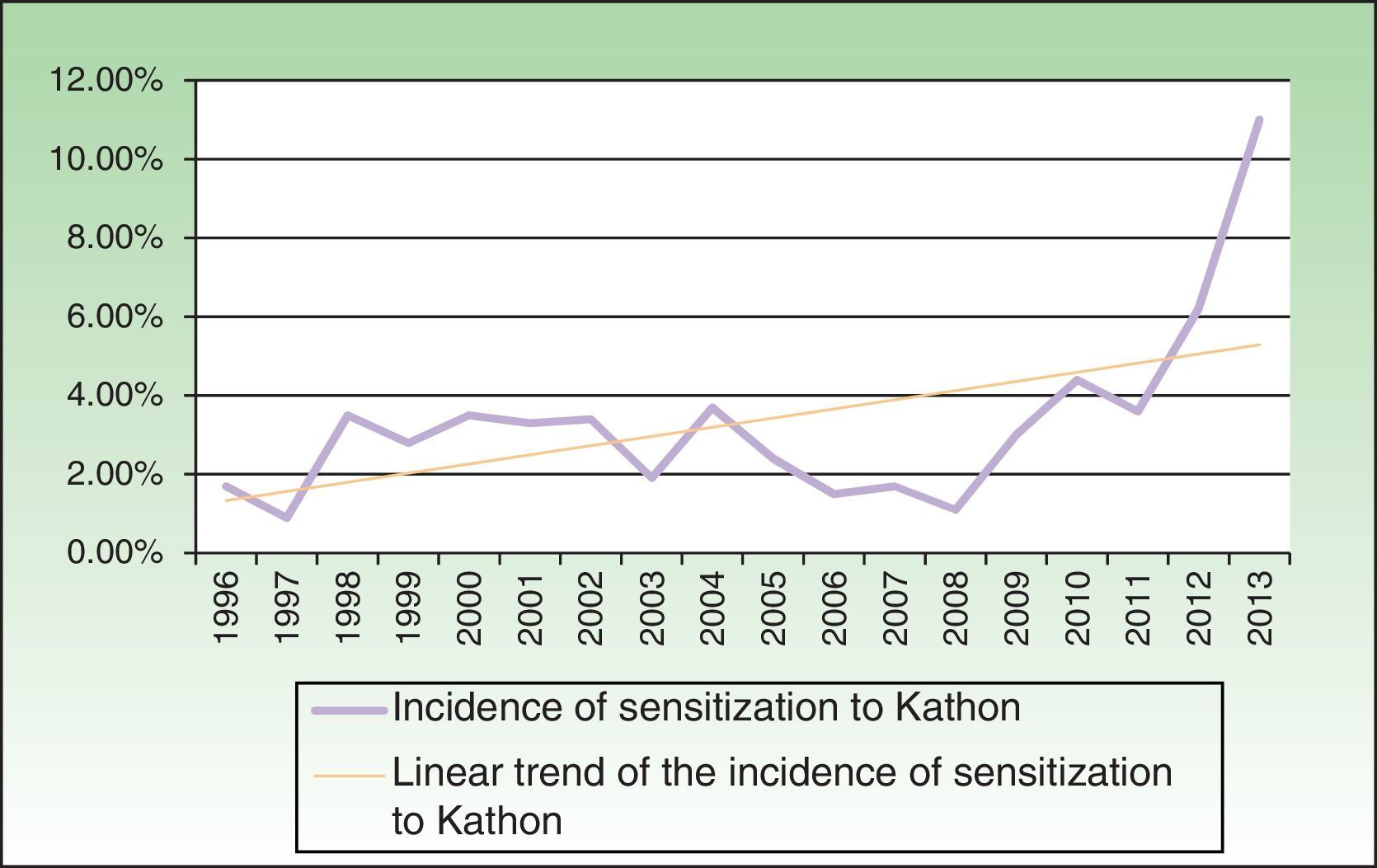

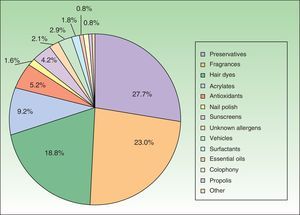

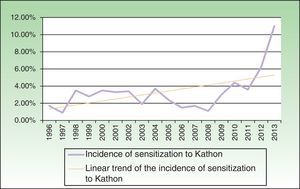

Preservatives were the most frequent cause of ACD to cosmetics (227 patients), growing from 2.2% in 1996 to 12.8% in 2013, mainly owing to the increase in cases of ACD to Kathon (172 patients), whose incidence increased 6-fold (1.7% in 1996 and 11.0% in 2013) (Fig. 6). Also noteworthy is the high frequency of positive results to methylisothiazolinone, which has been patch tested alone at 500ppm since 2012 (incidence of sensitization, 3.5% in 2012 and 8.8% in 2013); in up to 13.8% of cases, positive results to methylisothiazolinone alone were not accompanied by positive results to Kathon.

Despite the fact that euxyl K400 was the second most frequent cause of preservative-induced ACD, with a peak incidence during the years immediately following 2000 (incidence of sensitization of 2% and accounting for 15% of all causes of ACD to cosmetics), cases of ACD to euxyl decreased considerably during the second half of 2000, with no reports of cases since 2008.

Formaldehyde and formaldehyde releasers were the third most common cause of preservative-induced ACD, although their incidence has remained at <1%. The most frequent formaldehyde releaser was quaternium 15, followed by diazolidinyl urea, bronopol, and imidazolidinyl urea.

The incidence of ACD to parabens was remarkably low (0.2%) throughout the study period and in each period.

Fragrances were the second most common cause of ACD to cosmetics (149 patients, 23.7%). An upward trend was observed with an increase in incidence during the second period from 6.7% to 13.7%. The most common marker was fragrance mix 1, whose incidence increased from 1.4% in 1996 to 4.8% in 2013. The frequency of positive reactions to the individual fragrances was 91.1%. The most common fragrances (in decreasing order) were isoeugenol, oakmoss, geraniol, eugenol, and cinnamic alcohol. Balsam of Peru affected very few patients (17 patients). However, we recorded a notably high incidence of positive results to the new markers in the Spanish standard series, for example, fragrance mix 2 (21 patients; 50% of all positive results for individual allergens, 80% to lyral) and lyral (15 patients).

PPDA was the third most frequent cause of ACD to cosmetics (135 patients [21.5%]) with an upward trend (increase in incidence from 2.0% to 3.2% in the second period). Depending on the source of sensitization, we identified 2 epidemiological profiles:

- -

Hair dyes (82%). Hair dyes mainly affected women (91%) with a mean age of 39.3 years, causing dermatitis on the head and neck. In occupational cases (15.9%), the mean age was 30.0 years (10 years earlier than nonoccupational cases), and the condition manifested as hand eczema.

- -

Henna tattoos (18%). No female predominance was observed for henna tattoos (in fact, 54% of patients were men), the mean age was lower (15.4 years [range, 4-29]), and dermatitis was located on the limbs and trunk.

Acrylates were the fourth most frequent cause of ACD to cosmetics (40 patients). Of note, most (88%) were diagnosed during the second period of the study. The most frequent manifestation was dermatitis on the fingertips in beauticians (67.5% were occupational), which was associated with contact with porcelain nails, gel nails, and semipermanent nail polish. The most common acrylates were hydroxyethyl methacrylate, ethylene glycol dimethacrylate, hydroxypropyl methacrylate, and hydroxyethyl acrylate (75% of patients sensitized to acrylates had positive results for all 4 allergens).

Other less common allergens (incidence of <1% in patients referred for patch testing) included the following:

- -

Antioxidants, essentially gallates (propyl gallate being the most frequent), which were the fifth most common cause of ACD to cosmetics (34 patients) and were associated with lipstick-induced cheilitis.

- -

Nail care cosmetic allergens, essentially toluene sulfonamide formaldehyde resin, which was the sixth most common cause (31 patients), with 80% of cases identified during the first period. This allergen was associated with eyelid eczema caused by contact with nail polish.

- -

Sunscreens were the seventh most common cause of ACD to cosmetics (23 patients). A growing trend was observed in recent years, with twice as many cases during the second period of the study. Oxybenzone was the most frequent allergen (9 patients), although octocrylene was an emerging allergen in the second period (7 patients), and methoxydibenzoylmethane was the third most frequent. The main manifestation was photoallergic contact dermatitis (87%). ACD (3%) was caused mainly by octocrylene. Despite the fact that sunscreens were the most common source of sensitization (89%), the frequency of lipstick and moisturizing cream was also remarkable (7% and 4%, respectively).

The 11.6% prevalence of ACD to cosmetics in patients referred for patch testing in our study is similar to values published in the Spanish medical literature, namely, 9%-11%.6–9 Furthermore, and in line with more recent studies, we detected an upward trend, which in recent years reached values of up to 15% and 20%,3,5,10 similar to the 18.9% we reported in 2013. Today, cosmetics are responsible for more than half of all cases of ACD.5

In epidemiological terms, we agree with previous findings that female sex is a risk factor11 and that ACD to cosmetics mainly affects middle-aged adults (40 years),8 who generally have no history of atopy and whose occupations have low academic requirements.12

The condition manifests as eczema on the face, neck, eyelids, and hands.4,11,13

Preservatives, fragrances, and PPDA are responsible for up to 80% of all allergies to cosmetics, and this trend has remained stable during the last few decades.14

With respect to preservatives, it is noteworthy that methylchloroisothiazoline/methylisothiazolinone has been the most common cause of ACD to cosmetics since the 1990s,15 despite regulatory measures restricting concentrations to 7.5ppm and 15ppm in leave-on and rinse-off products16 and the fact that authorization of high-concentration methylisothiazolinone alone (up to 100ppm) has triggered a veritable epidemic of ACD to Kathon, reaching values greater than 10% and thus triggering health care alarms about the need to regulate it.17

The regulation applying to euxyl k40018 in particular has relegated this allergen to the second most common preservative, as its incidence fell and disappeared since it was prohibited in 2008.15

Consequently, formaldehyde and formaldehyde releasers are the most relevant preservatives after the isothiazolinones, although the incidence of ACD to these allergens is low (<1%).15,19

Particularly low—even exceptional—is ACD to parabens15,20: we detected ACD in only 11 of the 5419 patients tested.

As for fragrances, incidence is noteworthy in the general population (1.7%-4.1%) and in patients referred for testing (up to 13.6%).5,21,22 The ubiquity of parabens is also remarkable, as they are the main sources of sensitization in cosmetics that are not heavily perfumed, such as gel and moisturizing cream.5 Furthermore, the incorporation of new markers in the standard series (eg, fragrance mix 2 and lyral) and in the individual fragrance series facilitates both diagnosis of ACD to fragrances and secondary prevention.23

PPDA is the third most common cause of ACD to cosmetics, and the high prevalence of sensitization to this allergen (women, 4.1%; men, 2.3%) is growing.24 Black henna tattoos are a public health problem, and hairdressers are an at-risk occupational group, with an incidence of dermatitis of more than 50%, of which 80% of cases are ACD.25 Also remarkable is the high rate of positive results we detected for the hairdresser series (56%), which coincides with some studies, such as that by Sosted et al. (62%).26 Consequently, there is a need to include black henna in the diagnostic workup for intolerance to dyes, since these can contain more than 200 allergens, of which up to 75% are potent sensitizers.

Cosmetic nail products are the fourth most common cause of ACD after gels, moisturizing cream, and hair products and are becoming more frequent with the boom in nail salon services.27 Although toluene sulfonamide formaldehyde resin has traditionally been the allergen associated with eyelid eczema caused by nail varnish, it has recently been overtaken by acrylates (components in modern nail sculpting techniques) and emerging allergens that generally cause fingertip dermatitis in beauticians.28

Skin allergy to sunscreens continues to be very rare despite the widespread use of these products and their incorporation in many cosmetic products. Benzophenone 3 is clearly the most common allergen,29 although octocrylene is an emerging allergen, for which an association with ACD caused by primary sensitization to children's sunscreen has been reported.30

Finally, we would like to draw attention to the high and growing prevalence of ACD to cosmetics in our setting, the usefulness of testing with the patient's own products despite the high yield of the standard series, and the need for a more professional approach to patients with suspected ACD involving a workup in the skin allergy clinic.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of humans and animalsThe authors declare that no tests were carried out in humans or animals for the purpose of this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no private patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors obtained informed consent from the patients and/or subjects referred to in this article. This document is held by the corresponding author.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Zaragoza-Ninet V, Blasco Encinas R, Vilata-Corell JJ, Pérez-Ferriols A, Sierra-Talamantes C, Esteve-Martínez A, et al. Dermatitis alérgica de contacto a cosméticos, estudio clínico-epidemiológico en un hospital terciario. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:329–336.