Skin problems are among the most frequent reasons for seeking medical attention in primary care. In recent years, as a result of the process of adapting medical curricula to the requirements of the European Higher Education Area, the amount of time students spend learning the concepts of dermatology has been reduced in many universities.

Material and methodsIn order to reach a consensus on core content for undergraduate education in dermatology, we sent a survey to the 57 members of the instructors’ group of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV), asking their opinions on what objectives should be set for a dermatology course in Spain. A total of 131 previously selected objectives were listed. We then applied the Delphi method to achieve consensus on which ones the respondents considered important or very important (score ≥4 on a Likert scale).

ResultsNineteen responses (33%) were received. On the second round of the Delphi process, 68 objectives achieved average scores of at least 4. The respondents emphasized that graduates should understand the structure and functions of the skin and know about bacterial, viral, and fungal skin infections, the most common sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), and the 4 main inflammatory dermatoses. Students should also learn about common complaints, such as itching and bald patches; the management of dermatologic emergencies; purpura and erythema nodosum as signs of internal disease; and the prevention of STDs and skin cancer. During clinical clerkships students should acquire the communication skills they will need to interview patients, write up a patient's medical history, and refer the patient to a specialist.

ConclusionsThe AEDV's group of instructors have defined their recommendations on the core content that medical faculties should adopt for the undergraduate subject of dermatology in Spain.

Los problemas dermatológicos constituyen uno de los motivos de consulta más frecuentes en atención primaria. En los últimos años, como consecuencia de la adaptación al espacio europeo de educación superior, en muchos planes de estudios se ha reducido el tiempo destinado al aprendizaje de la dermatología.

Material y métodosPara consensuar los contenidos básicos del programa de dermatología en el pregrado, se remitió electrónicamente una encuesta a los 57 miembros de grupo de profesores de la Academia Española de Dermatología y Venereología para establecer cuáles deberían ser los objetivos de aprendizaje de la asignatura en España. Se incluyeron 131 objetivos previamente seleccionados, buscándose un consenso mediante el método Delphi sobre los objetivos importantes o muy importantes (puntuación ≥4).

ResultadosSe obtuvieron 19 respuestas (33%). Tras una segunda ronda de consenso 68 objetivos alcanzaron una puntuación ≥4 de promedio en la escala de Likert. Destacan que los graduados conozcan la estructura y las funciones de la piel, las infecciones bacterianas, víricas, micóticas y de transmisión sexual frecuentes, las 4 principales dermatosis inflamatorias, algunos problemas comunes como el prurito y la alopecia en placas, el manejo de dermatosis urgentes, la púrpura y el eritema nudoso como signos de enfermedad interna y reconocer algunos tumores cutáneos benignos y el cáncer de piel, así como la prevención de las enfermedades de transmisión sexual y del cáncer cutáneo. Además, durante las prácticas clínicas, deberían adquirir las habilidades de comunicación necesarias para realizar una entrevista y redactar una historia clínica dermatológica y una hoja de derivación.

ConclusionesSe definen los contenidos considerados fundamentales para impartir en las facultades de medicina y recomendados por el grupo de profesores y docentes de la Academia Española de Dermatología y Venereología.

Among the most frequent reasons patients visit primary care physicians are skin problems, which account for between 7% and 10.2% of consultations in some series.1–4 Nevertheless, little time is assigned to the subject of dermatology in undergraduate medical studies.5 Students in the United States receive an average of 18hours of classroom instruction in medical school.6 Since the creation of the European Higher Education Area, Spain has assigned 2.8 credits (under the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System), an amount that is far from the average of 3.4 credits assigned elsewhere according to unpublished data from a 2008 survey reported at the national conference of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV) in Barcelona.

In 2012, members of the instructors’ group of the AEDV met at the national conference in Oviedo and agreed to conduct a survey to reach consensus on the core content to recommend for a Spanish undergraduate dermatology course.

Material and MethodsWe took the learning objectives proposed by Clayton et al.7 for the United Kingdom, grouped under the following headings: basic concepts, dermatologic emergencies, acute skin failure, inflammatory dermatoses, skin infections, preventive medicine, common dermatologic problems, tumors, signs of systemic disease, management and therapeutics, and skills for managing clinical visits with patients. We added sexually transmitted diseases, a category not covered by the specialty of dermatology in the UK.

Early in 2013, a preliminary online survey naming 131 learning objectives was sent to 57 members of the instructors’ group of the AEDV; the members were asked to rate each on a Likert scale from 1 (unimportant) to 5 (very important). Afterwards we collected all objectives rated important or very important (mean score, ≥4) to comprise the curriculum of a course to prepare medical school graduates to manage common, important skin problems seen in primary care clinical practice. A modified Delphi method was used to reach consensus.

A second survey was conducted in February 2014 to confirm the level of agreement on the objectives extracted from the earlier survey. The respondents were asked to express their full approval of an objective (response, “OK”), their belief that content should be added to an objective (response, “A” plus specification of the content proposed), or their opinion that an objective was not unimportant enough to include or not relevant (response, “NR”). Objectives were considered acceptable only if over half the instructors agreed they were important.

Respondents were also asked about various aspects of undergraduate teaching, as follows: the academic year when the course should be offered, how theoretical knowledge should be assessed, whether or not the instructor practiced ongoing, or formative, assessment at some point or points mid-course, and whether clinical clerkships were included and how performance in them was assessed.

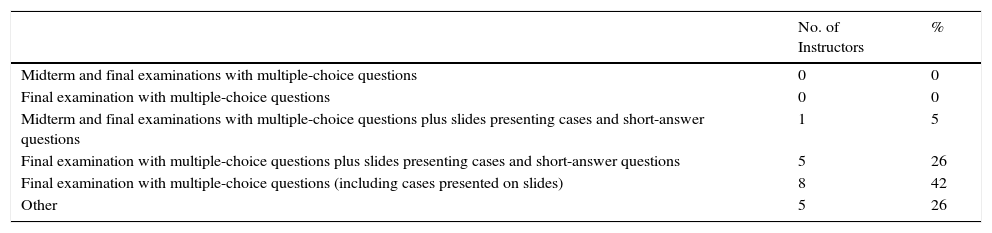

ResultsFrom the 57 members of the AEDV instructors’ group, 19 returned completed surveys (response rate, 33%). The respondents included 5 full professors, 11 other tenured professors, and 3 adjunct instructors associated with 15 universities. Fifty-three percent of the universities offered dermatology in the fifth year of undergraduate studies, whereas 26% offered the subject in the fourth year. The content was taught through lectures, ranging in number from 20 to 40. Case studies were also used in 1 university, and a problem-based learning approach was used in 2 universities. Nearly 70% of the instructors gave a multiple-choice final examination, including case presentations followed by questions (for short written answers or multiple-choice responses) (Table 1). One instructor used other types of evaluation during the course. Half the universities included fewer than 20hours of clerkships; 26% included between 20 and 30hours. Twenty percent used objective means for evaluating student performance in the clerkships, and the grades given contributed a significant portion of the final mark in the course; in contrast, 20% of the instructors did not assess performance in clerkships.

Methods for Testing Basic Theoretical Concepts.

| No. of Instructors | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Midterm and final examinations with multiple-choice questions | 0 | 0 |

| Final examination with multiple-choice questions | 0 | 0 |

| Midterm and final examinations with multiple-choice questions plus slides presenting cases and short-answer questions | 1 | 5 |

| Final examination with multiple-choice questions plus slides presenting cases and short-answer questions | 5 | 26 |

| Final examination with multiple-choice questions (including cases presented on slides) | 8 | 42 |

| Other | 5 | 26 |

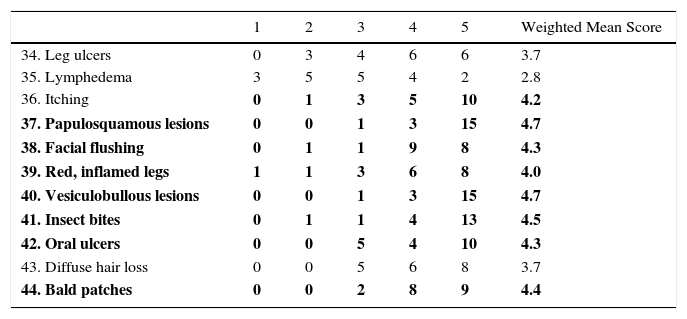

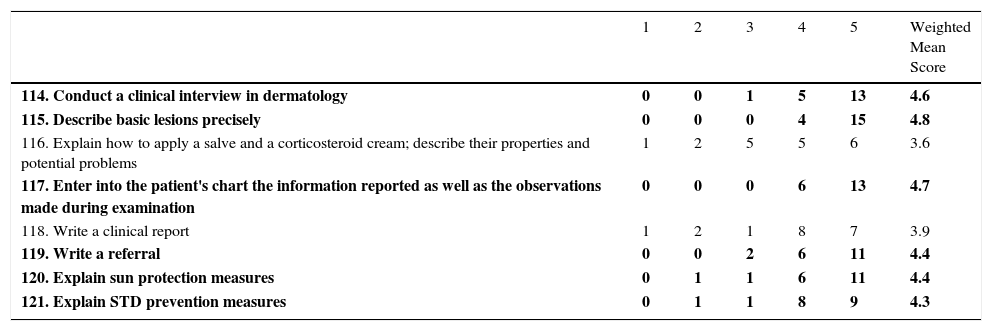

Only 71 of the 131 learning objectives proposed for evaluation in the first-phase survey received a score of 4 or more. The objectives ranked highest (average score >4.5) were the description of dermatologic signs and the management of common infections (impetigo, folliculitis, herpes virus infection, warts, molluscum contagiosum, and mycoses), the 4 typical inflammatory conditions (atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, psoriasis, and acne), the main sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) (syphilis, urethritis, and cervicitis), and first aid for dermatologic emergencies (Stephen-Johnson/Lyell syndrome, purpura, and urticaria-angioedema). Also important were benign tumors (melanocytic nevi), premalignant tumors (actinic keratoses), and malignant tumors of the skin (basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas and melanomas). Similar scores were achieved by the following concepts: structure and functions of the skin, vesiculobullous lesions, erythema (nodosum and multiforme), and skin cancer prevention. Topics that achieved slightly lower mean scores (but still >4) were as follows: common skin problems such as pruritus; facial flushing and red, inflamed legs; bald patches; and oral ulcers (Table 2); and certain cutaneous manifestations of internal diseases, such as photosensitivity, scleroderma, and koilonychia. In the category of therapeutics, the respondents thought the students should be able to distinguish between lotions, creams, pomades, and salves as well as describe the fundamental uses of corticosteroids, antibiotics, antifungals, and topical calcineurin inhibitors. The students should also learn about the use of prednisone among oral treatments and be able to describe the basics of surgery to treat skin cancer. The competencies students should attain through patient contact during clinical clerkships were as follows according to the surveyed instructors: question a patient about dermatologic problems, describe basic lesions precisely, record the patient's description and the student's observations in the patient's chart, write up a referral to a specialist, explain sun protection measures for preventing skin cancer, and explain measures for preventing STDs (Table 3). None of the technical skills inherent to the specialty of dermatology were designated as fundamental objectives for an undergraduate course.

Important Common Skin Problems Included in the Proposed Learning Objectivesa

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Weighted Mean Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 34. Leg ulcers | 0 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 3.7 |

| 35. Lymphedema | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2.8 |

| 36. Itching | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 10 | 4.2 |

| 37. Papulosquamous lesions | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 15 | 4.7 |

| 38. Facial flushing | 0 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 8 | 4.3 |

| 39. Red, inflamed legs | 1 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 4.0 |

| 40. Vesiculobullous lesions | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 15 | 4.7 |

| 41. Insect bites | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 13 | 4.5 |

| 42. Oral ulcers | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 10 | 4.3 |

| 43. Diffuse hair loss | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 3.7 |

| 44. Bald patches | 0 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 9 | 4.4 |

Oral and Written Communication Skillsa

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Weighted Mean Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 114. Conduct a clinical interview in dermatology | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 13 | 4.6 |

| 115. Describe basic lesions precisely | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 15 | 4.8 |

| 116. Explain how to apply a salve and a corticosteroid cream; describe their properties and potential problems | 1 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 3.6 |

| 117. Enter into the patient's chart the information reported as well as the observations made during examination | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 13 | 4.7 |

| 118. Write a clinical report | 1 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 3.9 |

| 119. Write a referral | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 11 | 4.4 |

| 120. Explain sun protection measures | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 11 | 4.4 |

| 121. Explain STD prevention measures | 0 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 9 | 4.3 |

Abbreviation: STD, sexually transmitted disease.

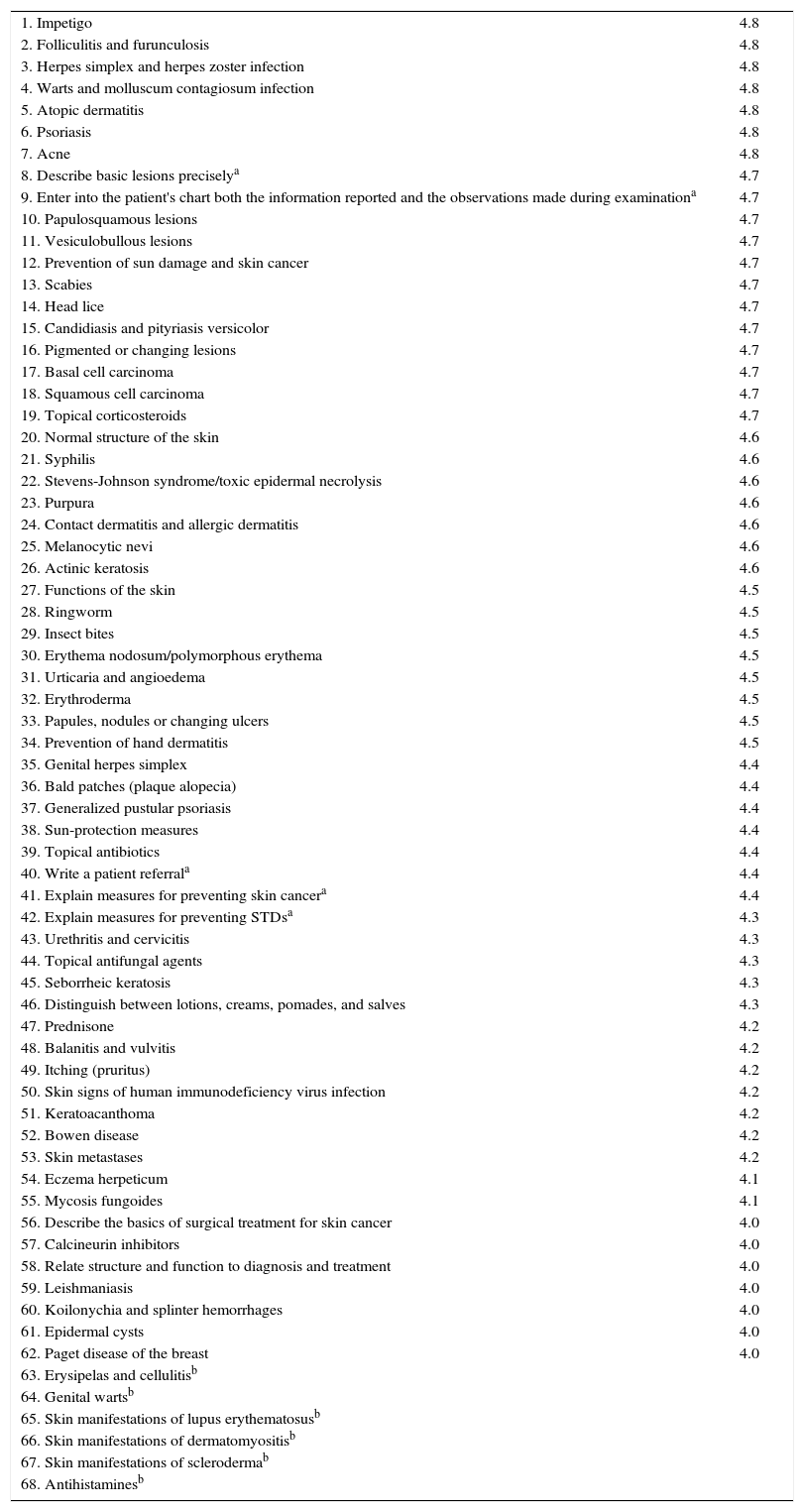

Nineteen responses were also received in the second round of the Delphi process (corresponding to the same 33% response rate of the first round). However, in this round the respondents were 5 full professors, 9 other tenured professors, and 5 adjunct instructors; they were affiliated with 13 of the 15 universities from which first-round responses had been received. The second-round results showed unanimous agreement about adding erysipelas, cellulitis, and genital warts to the list of infections; oral antifungal agents and antihistamines were added to the list of therapeutic measures students should learn about. Respondents asked that facial flushing be dropped from the list and that it be replaced by the skin manifestations of lupus erythematosus and dermatomyositis, rosacea, and seborrheic dermatitis. It was also suggested that inflammation of the legs was a concept that was little used in Spain and should be removed. The 68 learning objectives on which the respondents reached consensus are summarized in Table 4, ranked in order of mean score achieved. Confusing concepts have been removed. This list will be presented to Spanish medical faculties as reflecting the recommendations of the instructors’ group of the AEDV.

List of 68 Learning Objectives Recommended by the Instructors’ Group of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV), Ranked According to Mean Score.

| 1. Impetigo | 4.8 |

| 2. Folliculitis and furunculosis | 4.8 |

| 3. Herpes simplex and herpes zoster infection | 4.8 |

| 4. Warts and molluscum contagiosum infection | 4.8 |

| 5. Atopic dermatitis | 4.8 |

| 6. Psoriasis | 4.8 |

| 7. Acne | 4.8 |

| 8. Describe basic lesions preciselya | 4.7 |

| 9. Enter into the patient's chart both the information reported and the observations made during examinationa | 4.7 |

| 10. Papulosquamous lesions | 4.7 |

| 11. Vesiculobullous lesions | 4.7 |

| 12. Prevention of sun damage and skin cancer | 4.7 |

| 13. Scabies | 4.7 |

| 14. Head lice | 4.7 |

| 15. Candidiasis and pityriasis versicolor | 4.7 |

| 16. Pigmented or changing lesions | 4.7 |

| 17. Basal cell carcinoma | 4.7 |

| 18. Squamous cell carcinoma | 4.7 |

| 19. Topical corticosteroids | 4.7 |

| 20. Normal structure of the skin | 4.6 |

| 21. Syphilis | 4.6 |

| 22. Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis | 4.6 |

| 23. Purpura | 4.6 |

| 24. Contact dermatitis and allergic dermatitis | 4.6 |

| 25. Melanocytic nevi | 4.6 |

| 26. Actinic keratosis | 4.6 |

| 27. Functions of the skin | 4.5 |

| 28. Ringworm | 4.5 |

| 29. Insect bites | 4.5 |

| 30. Erythema nodosum/polymorphous erythema | 4.5 |

| 31. Urticaria and angioedema | 4.5 |

| 32. Erythroderma | 4.5 |

| 33. Papules, nodules or changing ulcers | 4.5 |

| 34. Prevention of hand dermatitis | 4.5 |

| 35. Genital herpes simplex | 4.4 |

| 36. Bald patches (plaque alopecia) | 4.4 |

| 37. Generalized pustular psoriasis | 4.4 |

| 38. Sun-protection measures | 4.4 |

| 39. Topical antibiotics | 4.4 |

| 40. Write a patient referrala | 4.4 |

| 41. Explain measures for preventing skin cancera | 4.4 |

| 42. Explain measures for preventing STDsa | 4.3 |

| 43. Urethritis and cervicitis | 4.3 |

| 44. Topical antifungal agents | 4.3 |

| 45. Seborrheic keratosis | 4.3 |

| 46. Distinguish between lotions, creams, pomades, and salves | 4.3 |

| 47. Prednisone | 4.2 |

| 48. Balanitis and vulvitis | 4.2 |

| 49. Itching (pruritus) | 4.2 |

| 50. Skin signs of human immunodeficiency virus infection | 4.2 |

| 51. Keratoacanthoma | 4.2 |

| 52. Bowen disease | 4.2 |

| 53. Skin metastases | 4.2 |

| 54. Eczema herpeticum | 4.1 |

| 55. Mycosis fungoides | 4.1 |

| 56. Describe the basics of surgical treatment for skin cancer | 4.0 |

| 57. Calcineurin inhibitors | 4.0 |

| 58. Relate structure and function to diagnosis and treatment | 4.0 |

| 59. Leishmaniasis | 4.0 |

| 60. Koilonychia and splinter hemorrhages | 4.0 |

| 61. Epidermal cysts | 4.0 |

| 62. Paget disease of the breast | 4.0 |

| 63. Erysipelas and cellulitisb | |

| 64. Genital wartsb | |

| 65. Skin manifestations of lupus erythematosusb | |

| 66. Skin manifestations of dermatomyositisb | |

| 67. Skin manifestations of sclerodermab | |

| 68. Antihistaminesb |

Abbreviation: STD, sexually transmitted diseases.

Skin diseases are among the most frequent reasons patients seek medical attention in primary care, and referrals to specialists in dermatology rank third in number (after gynecology and ophthalmology) in Spain.8 Family practitioners have been shown to have inadequate preparation in dermatology, even though it is clear that they must effectively manage common, mild skin problems such as infections, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis or acne—as well as recognize common benign tumors and premaligant and malignant ones.9 Clinical clerkships are key to acquiring the necessary competencies in dermatology,10 and students in the United Kingdom who have had such experiences and received training in small groups have been shown to diagnose conditions with greater confidence.11 Another UK study that evaluated the competencies of medical interns (first foundation year) in 6 hospitals found that those who had received more than 10 days of hospital training were significantly better prepared to take a patient's medical history, perform an examination, and manage dermatologic emergencies and skin tumors.12 When a third study assessed University of Edinburgh students’ precision in diagnosing 16 skin tumors before and after 10-day rotations in dermatology clinics, significant improvements were seen.13 Other attributes that can only be developed through contact with patients are empathy and communication skills.10

Concerned about the reduction in credits assigned to dermatology by some Spanish medical faculties, the instructors’ group of the AEDV decided to determine the fundamentals to be covered in undergraduate courses in the specialty (i.e., a core curriculum). We began by studying similar curricula adopted in the UK7; Canada14; East Asia and Australia15; Germany, Austria, and Switzerland16; and the United States.17 These different countries’ curricula had points of overlap. A UK study by a multidisciplinary group that included instructors in dermatology, internal medicine, family practice, and pediatrics—as well as dermatology nurses7—provided a point of reference for the present study. However, because the UK study was multidisciplinary, its results differed from ours. For example the authors designated cutaneous signs of acute meningococcemia and necrotizing fascitis as learning objectives but did not include the management of erythroderma. Nor did they recommend that students learn to make recommendations related to the transmission of STDs, given that managing such infections corresponds to another specialty in the UK. Standards for undergraduate medical education are defined by the UK's General Medical Council and published in a report entitled Tomorrow's Doctors, which provides a framework that has been applied in each medical specialty, including dermatology. (See Dermatology in the Undergraduate Medical Curriculum, available from www.bad.org.uk/shared/; cited September 5, 2014.) The results of the UK study were sent to 29 medical faculties in 2006.

Medical schools in the United States allot an average of 10hours,17 an amount considered inadequate.18 Students of medicine are also given the opportunity to opt for 2-week rotations in dermatology, but only 25% to 30% of fourth-year students take up the offer.19 Such scarce contact with the subject represents an impediment for medical students’20 or residents’21 acquisition of skills for confidently diagnosing skin cancer or managing common skin diseases. When the directors of 109 hospitals and 33 medical school instructors were surveyed they agreed that students should learn to diagnose and treat 33 skin diseases by the time they complete a rotation in dermatology.17

Canada revised the dermatology curricula in 1983, 1987 and 1996, finding on each occasion that there was limited exposure to the specialty. One survey of dermatology coordinators at 17 medical schools found that the number of hours devoted to dermatology had increased from 7hours to a mean (SD) of 20.5 (17.2).14 The subject of dermatology is mainly taught by nondermatologists in Canadian medical schools, however, given the scarcity of specialists who teach.

When the University of Hamburg developed new objectives for orienting the subject of dermatology in medical faculties, material related to andrology and basic phlebology were included.22 Their program organizes the subject in teaching modules that integrate introductory lectures, symptom-oriented lectures, problem-based tutorials, and skills that are important for practicing general medicine.22

New computer-based (e-learning) resources to enhance self-directed learning have made their appearance in our specialty in recent years. Online learning tools allow a student to view hundreds of images at very low cost any time of day, resolving the problem of an increasing number of students spread out across various learning centers. Users learn dermatology through pattern recognition, followed by an analytical process of categorization and comparison with previously known or studied cases. Nonanalytical reasoning also plays a part: intuitive skills emerge while students view many images in a process that demands little effort and often takes place on an unconscious level and is therefore difficult to express to others.23 E-learning also facilitates the presentation and solving of case problems, although less effectively than clinical clerkships do. US experts in medical education and directors of residency programs in internal medicine, pediatrics, and family medicine have developed an online dermatology program under the auspices of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) in an attempt to address the problem of underexposure to the subject. Available from http://www.aad.org/education/basic-dermatology-curriculum (cited September 1, 2014), this tool covers the fundamentals of dermatology for medical students and residents in family medicine. Each module can be studied in 20 to 40minutes. When the impact of 18 modules on student learning was evaluated with a 50-item test before and after a rotation, 51 users had improved their knowledge of dermatology significantly and expressed satisfaction with the navigability of the site and the time they had invested.24 Another study assessed knowledge acquired by fourth-year medical students and family practice residents after they used the AAD tool during a 2-week rotation in dermatology clinics.25 Their knowledge also improved significantly, and the students preferred the interactivity of the website to the traditional media of textbooks and lectures. A project called DEJAVU (for Dermatological Education as Joint Accomplishment of Virtual Universities) has been organized by the Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin medical school.26 This e-learning project consists of an archive of conference recordings, handouts, structured learning modules and clinical cases as well as information for courses and specific classes. Students consult it for 14.7 hours, on average, during a semester. By the end of 2007, 93.5% of the students were familiar with DEJAVU, and 66.8% considered it very useful. The dermatology associations of Germany, Austria, and Switzerland created another program that is useful for both medical students and postgraduates in family and community medicine (Dermokrates, available from http://www.Dermokrates.com).16 In 2010, the Australasian College of Dermatologists introduced online modules they had developed in collaboration with the University of Sydney. When the results for students who used the modules were compared to the previous year's results,15 there were gains in knowledge, diagnostic skills, and management of common skin conditions in spite of a reduction in the number of hours spent in dermatology clerkships. The students ranked their learning experience significantly higher in dermatology than in other specialties.

E-learning resources are available at many Spanish universities. Of note are the universities of Valencia; the Rovira i Virgili in Reus, Tarragona; and of Lleida. The third offers the Dermatoweb (www.dermatoweb.net),27 which students have judged to be very useful. Fifty-six percent reported consulting it 3 or more times per week during their dermatology course, and a sample of 63 students gave the site a mean score of 4.4 out of 5 points. The site contains a section on the differential diagnosis of common skin diseases and tumors (“20 common complaints”), an atlas with more than 7000 photographs, a selection of videos about procedures and dermatologic surgery, material on the 32 topics included in the dermatology course offered by the university, and clinical cases with problems to solve and comments on model responses for self-directed learning. For most of the students, the website was their only study tool.

The main limitation of our study was the low response rate of 33%. Only 19 of the 57 eligible instructors completed the surveys, but the sample of full professors, other tenured professors, and adjunct instructors was sufficient to allow the group to reach a consensus on the essential objectives to include in a core dermatology curriculum for Spain. The absence of certain skin diseases that have traditionally been included in many dermatology curricula—such as leprosy, porphyria, ichthyosis, histiocytosis, and mastocytosis—may seem surprising. However, the topics recommended do reflect the important dermatologic problems that must often be managed in a general medical practice.

Finally, the AEDV is aware of the scarcity of resources available online for studying dermatology in Castilian Spanish. In order to encourage uniformity in the training of our students and family practitioners in dermatology, and in the interest of greater fairness in the national examination that gives graduates access to Spanish residency programs, the AEDV is proposing to develop online modules covering the learning objectives recommended by the instructors’ group.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that no private patient data are disclosed in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no private patient data are disclosed in this article.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Casanova JM, et al. Contenidos fundamentales de la Dermatología en el grado de medicina en España. Recomendaciones del grupo de profesores de la Academia Española de Dermatología y Venereología. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:125–132.

These results were presented at the Forty-second National Dermatology Conference in Maspalomas, Canary Islands, in June 2014.