Tattoos are permanent forms of body modification that date back since at least Neolithic times, as evidenced by ancient art and the archaeological records. The art of tattooing evolved independently in a multitude of different cultures all over the world and served extremely diverse purposes. Among the first to develop tattooing traditions were Ancient Greeks. Written records that provide evidence of tattooing date back to at least the 5th-century BCE1. During this era, tattooing was adopted as a punitive or proprietary action and represented a sign of distinction or social rank. Although the Ancient Greeks did not have tattoos on their bodies, they would use tattooing to penalize the outcasts of society. In general, tattoos were considered a barbaric custom and the upper social classes treated them with disdain2.

Ancient Greeks, according to the historian Herodotus (484-426 BC), learned both the idea of penal tattoos and the art of tattooing from the Persians around the sixth century B.C. His writings describe the use of tattoos in a disciplinary sense on captives, slaves, criminals, deserters and prisoners of war. Slaves in particular, used to be tattooed with the letter delta (δέλτα), the first letter of the word ‘δoῦλoς’, standing for ‘slave’. Prisoners condemned for hideous crimes would have their offenses inked into their foreheads or other easily visible locations. This would not only make then easily identifiable if they attempted to escape from imprisonment but would also continue their punishment even upon release. A plethora of other well-known ancient Greek authors and philosophers like Xenophon, Plato, Aristophanes, and Aelius Aristides describe this practice that was feared and despised by the Greek citizens, in their writings3,4.

Herodotus also reports that in 480 BC, shortly before the battle of Thermopylae, some Thebans, led by Leontiad were deserted and joined the Persians, as soon as they saw that the Persians prevailed. As a result, they were tattooed according to the Persian Kind Xerxes’ order. After the Persians’ defeat and their flight, it was impossible for them to return to Thebes as they were considered traitors. Plutarch describes the story of Athenians who, upon defeat of the Samians in a naval battle, tattooed the Samians’ foreheads with an owl, Athens’ hallowed emblem and symbol of wisdom. When some time later the Samians defeated the Athenians, they tattooed a “Samina”, a Samian warship, on them as a retaliation. Plutarch also describes how the Syracousian warriors tattooed a horse, the emblem of Syracuse, on 7000 captives’ foreheads, after the defeat of Athenians in Sicily, in 413 BCE3–5.

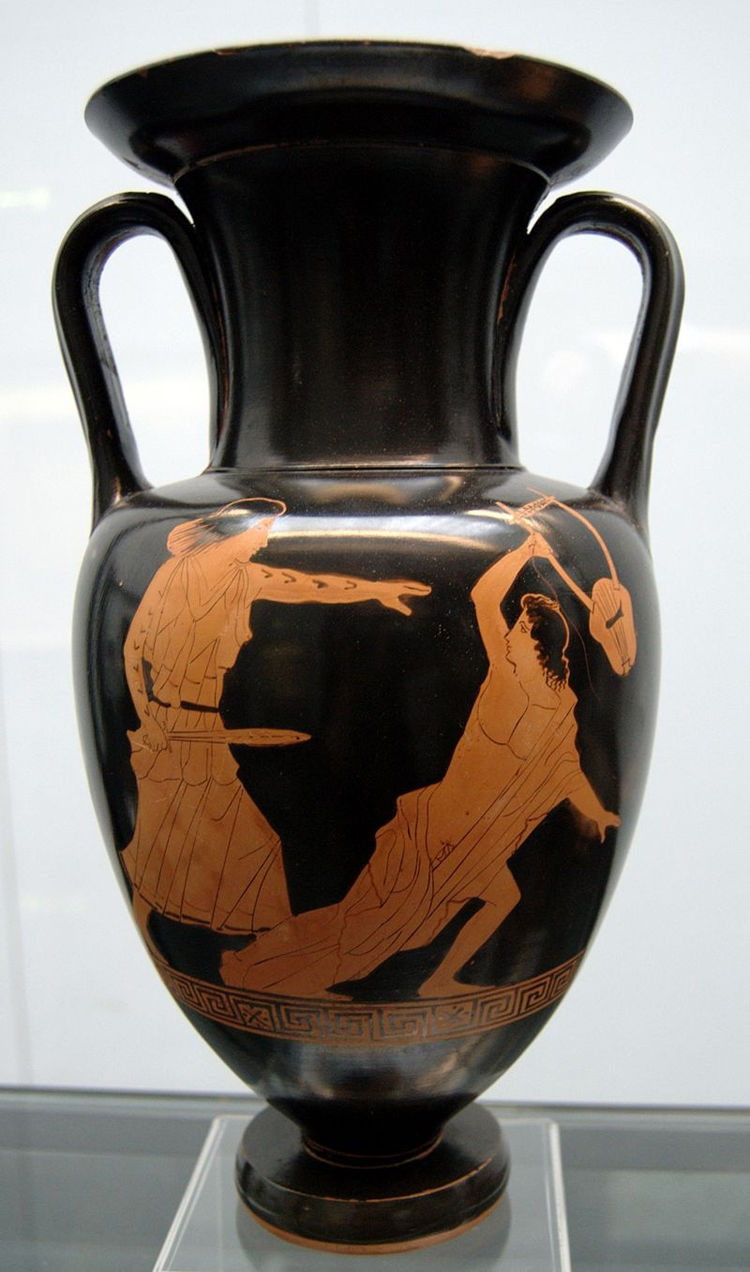

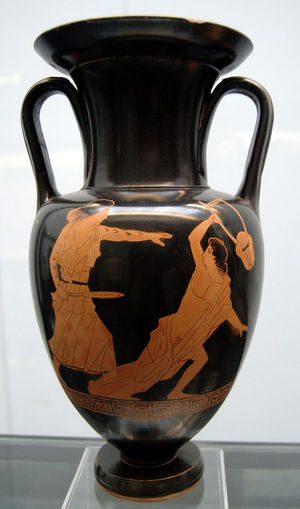

Both literary and archaeological evidence indicate that the only exception were the ancient Thracians. According to Herodotus, among them, the tattoos were a sign of courtesy and high social rank, while the lack of it was a mark of low birth4. On the contrary, tattooing was considered a mark of punishment on Thracian women (Maenads) for the dismemberment and decapitation of Orpheus, a legendary musician of antiquity, who -according to the myth- lured away their husbands with his music (Fig. 1)5.

Greek Red-Figure vase (450-440 B.C.) depicting the death of Orpheus by a sword-wielding, Thracian maenad bearing tattoos with geometric patterns on her bare arms. Amongst Thracian men, tattooing of men served as a marker of high social status and nobility that clearly distinguished the aristocracy from the peasantry. Conversely, the Greek essayist Plutarch suggests that Thracian women (Maenads), whose name roughly translates to the “Mad Women” or “Raving Ones, had been tattooed by their husbands as a punishment for killing Orpheus. Despite their misgivings about the practice, Ancient Greeks were also fascinated by the idea of tattoos. As a result, within the iconography of vase painting in the 5th and 4th centuries B.C., Greek artists frequently illustrated Thracian women wielding swords, spears, daggers and axes. On these vases, the geometric tattoos on the women’s bodies draw attention to athletic strength and are used to accentuate musculature and motion.

Another acceptable form of voluntary tattooing was as a way of relaying secret messages through enemy lines, as testified through the literary sources and the attic iconography. A famous example is that of Histiaeus, the tyrant of Miletus under Darius I, king of Persia, who had subjugated Miletus. When Histiaeus was imprisoned by Darius, around 500 B.C., the former shaved the head of his most trusted slave and tattooed the phrase ‘Aristagoras should revolt from the king’ on his scalp. When the slave’s hair grew back, he was sent to his son in law, Aristagoras, in an effort to inspire him to revolt. Upon reaching his destination the slave’s head was shaved again, Aristagoras read the message and launched the revolt that ended in the Persian invasion of Greece5.

The roots of the vision of the tattoos as a stigma go back in the ancient Greece, where the word stigma (στίγμα), was invented. In fact, the ancient Greek word for tattoo was dermatostiksia, deriving from the affix “derma” (δέρμα), meaning skin or hide, and the word stigma, which referred to the signs on the body which were commonly associated to delinquents and the depreciable aspects of people’s morality. The metaphorical application of stigma as a sign of disgrace or moral decay is of contemporary value as it does not deviate from the meaning of ‘stigma’ in modern English. In ancient Greece, the physical aspect was strongly related to a person’s moral values, an ideal summarized in the Greek expression ‘καλὸς κἀγαθός’ (meaning ‘the beautiful and the good’). A person would only be considered beautiful only if he or she was at the same time ethically good, and conversely2,3.

The use of tattoos as a sign of condemnation or slavery stopped with the prevalence of Christianity in Greece. Specifically, Emperor Constantine I explicitly banned facial tattoos around 330 AD, stating that man’s face was crafted in God’s image, and it was a sacrilege to deface it, regardless of the merit of the individual6. He suggested that the hands or calves should be tattooed instead. However, in 787 AD, the Second Council of Nicaea additionally banned all tattoos as a pagan practice3,7.

Although historically associated with deviant and marginalized populations during Greek antiquity, the employment of tattooing has gained recognition as a legitimate art form in the last quarter of the 20th century. Having changed in form and function since the Greek Era, contemporary tattooing is now widely accepted as a form of self-expression or fashion statement, widely practiced by individuals representing all socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Kyriakou G, Kyriakou A, Fotas Th. Dermatostiksia (tatuajes): un acto de estigmatización en la cultura griega antigua. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021;112:907–909.