Many skin diseases are associated with mental disorders. When the psychological symptoms are mild, as is often the case in dermatology, it can be difficult to distinguish between normality and the manifestations of a mental disorder. To facilitate the distinction we review the concept of mental disorder in the present article. It is also important to have instruments that can facilitate early detection of psychological disease, i.e. when the symptoms are still mild. Short, simple, self-administered questionnaires have been developed to help dermatologists and other health professionals identify the presence of a mental disorder with a high degree of certainty. In this article, we focus on the questionnaires most often used to detect the 2 most common mental disorders: anxiety and depression. Finally, we describe the circumstances in which it is advisable to refer a dermatological patient to a psychiatrist, who can diagnose and treat the mental disorder in accordance with standard protocols.

Muchas enfermedades dermatológicas van asociadas a trastornos psiquiátricos. No es fácil la distinción entre la normalidad y el trastorno psiquiátrico cuando la intensidad de los síntomas psicológicos es leve, como suele ocurrir en dermatología. Por eso revisamos el concepto de trastorno psiquiátrico. Por otra parte, son necesarios instrumentos para detectar una enfermedad psicológica de forma precoz, cuando los síntomas son todavía menores. Para ello se han desarrollado cuestionarios breves, sencillos, autoadministrados por el propio paciente, que ayudan a dermatólogos y demás profesionales sanitarios a sospechar con alto grado de certeza la existencia de una enfermedad psiquiátrica. Nos centraremos en los cuestionarios más utilizados que detectan las 2 enfermedades psiquiátricas más frecuentes: ansiedad y depresión. Por último, describiremos las circunstancias en las que es recomendable derivar a un paciente dermatológico al psiquiatra para que sea este quien le siga de forma reglada.

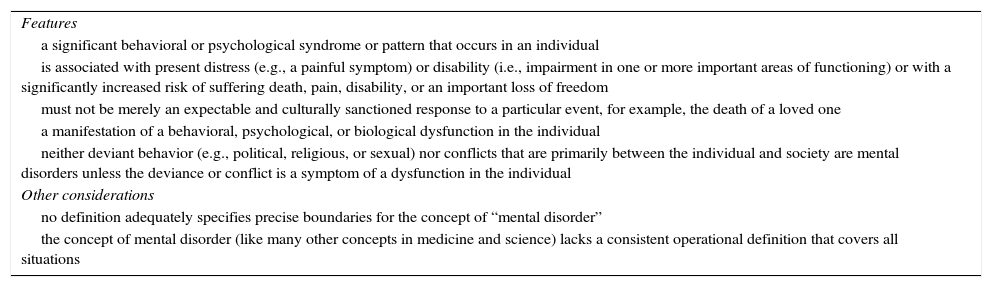

The definition of mental disorder according to the latest edition of the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders1 (DSM-V) is given in Table 1. According to estimates for 2020 by the World Health Organization, 1 in 4 people will be affected by a mental disorder at some point in their lives.2 Mental illness is one of the main causes of disease and disability worldwide, and currently affects around 450 million people.2 The relative proportion of cases seen in dermatology offices is even higher. According to a study by Gupta et al.,3 mental disorders are 20% more common in patients seen by dermatologists than in the general population, and between 20% and 30% more common in hospitalized patients with dermatologic disorders than other hospitalized patients.

Definition of Mental Disorder According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.1

| Features |

| a significant behavioral or psychological syndrome or pattern that occurs in an individual |

| is associated with present distress (e.g., a painful symptom) or disability (i.e., impairment in one or more important areas of functioning) or with a significantly increased risk of suffering death, pain, disability, or an important loss of freedom |

| must not be merely an expectable and culturally sanctioned response to a particular event, for example, the death of a loved one |

| a manifestation of a behavioral, psychological, or biological dysfunction in the individual |

| neither deviant behavior (e.g., political, religious, or sexual) nor conflicts that are primarily between the individual and society are mental disorders unless the deviance or conflict is a symptom of a dysfunction in the individual |

| Other considerations |

| no definition adequately specifies precise boundaries for the concept of “mental disorder” |

| the concept of mental disorder (like many other concepts in medicine and science) lacks a consistent operational definition that covers all situations |

The most common psychiatric disorder seen by dermatologists is depression.4 Survey-based data indicate that up to 30% of patients may have significant depression, and that up to 10% of outpatients with psoriasis may have experienced suicidal ideation.5 Obsessive-compulsive disorder may be present in between 10% and 15% of patients seeking dermatologic treatment, and over 10% have been reported to have body dysmorphic disorder.6

Psychological tests are experimental instruments designed to measure or assess an individual's specific psychological characteristics or general personality traits. Individual responses can then be evaluated by comparing them, either statistically or qualitatively, to those from other individuals who have undergone the same test. The results are then used to classify the person into a certain category. The test's design must ensure that the specific behavior being evaluated is a faithful as possible reflection of how the individual functions in everyday situations, which is where the capacity being evaluated is truly put to test.

Scales for the Early Detection of Anxiety and DepressionDermatologists have access to many scales that can be used to gain an initial diagnostic impression of an emotional or behavioral disorder,7 but these preliminary diagnoses must then be confirmed through a standardized psychiatric interview, such as the standardized neuropsychiatric interview.8

Examples of scales available to dermatologists are the Goldberg Anxiety and Depression Scale, the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, Yesavage's Geriatric Depression Scale (Short Form), the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale, the Beck Depression Inventory, Tyrer's Brief Scale for Anxiety, the Anxiety Screening Questionnaire, the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), the Hospital and Anxiety Depression Scale, and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7). In this review, we will provide a brief description of the scales that are most used in routine clinical practice due to their simplicity and validity.

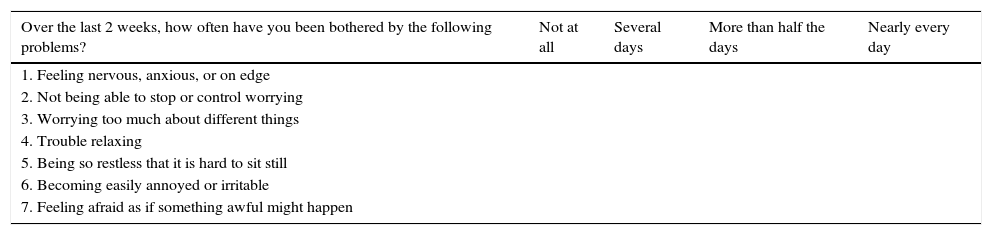

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) (Table 2)Although the GAD-7 was initially developed to detect and measure the severity of generalized anxiety disorder,9,10 it has since proven to have good psychometric properties for use in other types of anxiety disorders (Table 2).

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item Scale.

| Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by the following problems? | Not at all | Several days | More than half the days | Nearly every day |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge | ||||

| 2. Not being able to stop or control worrying | ||||

| 3. Worrying too much about different things | ||||

| 4. Trouble relaxing | ||||

| 5. Being so restless that it is hard to sit still | ||||

| 6. Becoming easily annoyed or irritable | ||||

| 7. Feeling afraid as if something awful might happen |

The GAD-7 consists of 7 items. The final score is calculated by assigning scores of 0, 1, 2, and 3 to four response categories, and adding up the score for the 7 items. The minimum possible score is therefore 0, while the maximum is 21. The cutoff scores are 5 for mild anxiety, 10 for moderate anxiety, and 15 for severe anxiety.

Based on the threshold score of 10, the GAD-7 has a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 82% for generalized anxiety disorder. It has also shown good results for screening for 3 other common anxiety disorders: panic disorder (sensitivity, 74%; specificity, 81%), social anxiety disorder (sensitivity, 72%; specificity, 80%), and posttraumatic stress disorder (sensitivity, 66%; specificity, 81%).

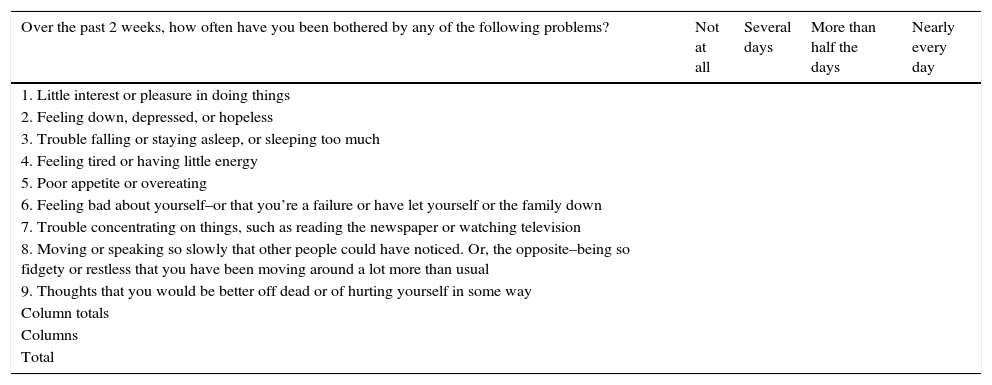

Depression: The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Table 3)The Patient Health Questionnaire, or PHQ, is a self-administered test for diagnosing mental disorders,11,12 while the PHQ-9 is a specific module of the test for assessing depression.9 The PHQ-9 contains 9 items corresponding to typical symptoms of depression; each item is scored on a scale of 0 to 3, depending on how often the patient has experienced the symptoms evaluated in the preceding 2 weeks. A score of 0 corresponds to “not at all”, while one of 3 corresponds to “nearly every day”. The total score for the PHQ-9 is calculated by adding up the scores for each of the 9 items (total possible score of 0 to 27). The PHQ-9 is used in nonpsychiatric settings and can be administered in Spanish or English. Individuals are classified as not having depression or as having possible or probable depression according to their total PHQ-9 score. Those with a score of under 8 are classified as not having depression, while those with scores of 9 and above are considered to have some level of depression (Table 3).

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).

| Over the past 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by any of the following problems? | Not at all | Several days | More than half the days | Nearly every day |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Little interest or pleasure in doing things | ||||

| 2. Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless | ||||

| 3. Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much | ||||

| 4. Feeling tired or having little energy | ||||

| 5. Poor appetite or overeating | ||||

| 6. Feeling bad about yourself–or that you’re a failure or have let yourself or the family down | ||||

| 7. Trouble concentrating on things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television | ||||

| 8. Moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have noticed. Or, the opposite–being so fidgety or restless that you have been moving around a lot more than usual | ||||

| 9. Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way | ||||

| Column totals | ||||

| Columns | ||||

| Total |

| 10. If you checked off any problems, how difficult have those problems made it for you to do your work, take care of things at home, or get along with people? | |||

| Not difficult at all | Somewhat difficult | Very difficult | Extremely difficult |

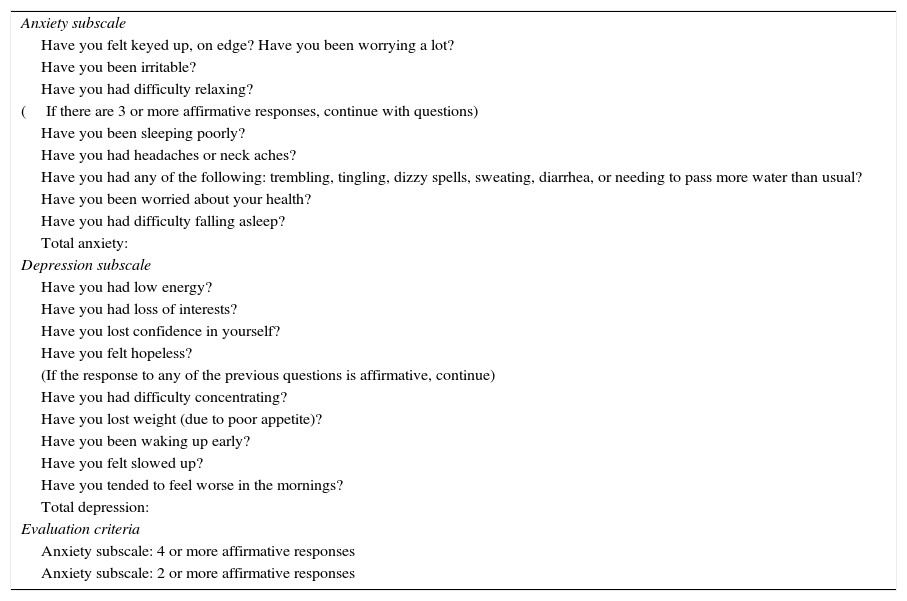

The GADS is used to both detect anxiety and depression in health care and epidemiological settings and to serve as an interview guide.13,14 Its purpose is not only to help in the diagnosis of anxiety and/or depression, but to also discriminate between the 2 disorders and measure their respective severity (Table 4).

Goldberg Anxiety and Depression Scale (GADS).

| Anxiety subscale |

| Have you felt keyed up, on edge? Have you been worrying a lot? |

| Have you been irritable? |

| Have you had difficulty relaxing? |

| (If there are 3 or more affirmative responses, continue with questions) |

| Have you been sleeping poorly? |

| Have you had headaches or neck aches? |

| Have you had any of the following: trembling, tingling, dizzy spells, sweating, diarrhea, or needing to pass more water than usual? |

| Have you been worried about your health? |

| Have you had difficulty falling asleep? |

| Total anxiety: |

| Depression subscale |

| Have you had low energy? |

| Have you had loss of interests? |

| Have you lost confidence in yourself? |

| Have you felt hopeless? |

| (If the response to any of the previous questions is affirmative, continue) |

| Have you had difficulty concentrating? |

| Have you lost weight (due to poor appetite)? |

| Have you been waking up early? |

| Have you felt slowed up? |

| Have you tended to feel worse in the mornings? |

| Total depression: |

| Evaluation criteria |

| Anxiety subscale: 4 or more affirmative responses |

| Anxiety subscale: 2 or more affirmative responses |

The GADS contains 2 subscales consisting of 9 questions each: the anxiety subscale (questions 1-9) and the depression subscale (questions 10-18). The first 4 questions on each subscale (questions 1-4 and 10-13, respectively) serve to determine whether or not the person should continue with the remaining questions on the scale. If the person does not answer at least 2 of the first 4 questions on the anxiety subscale affirmatively, he/she should not answer the rest of the questions on this scale. In the depression subscale, a person who answers “yes” to just one of first 4 questions (questions 10-13) should continue with the other questions.

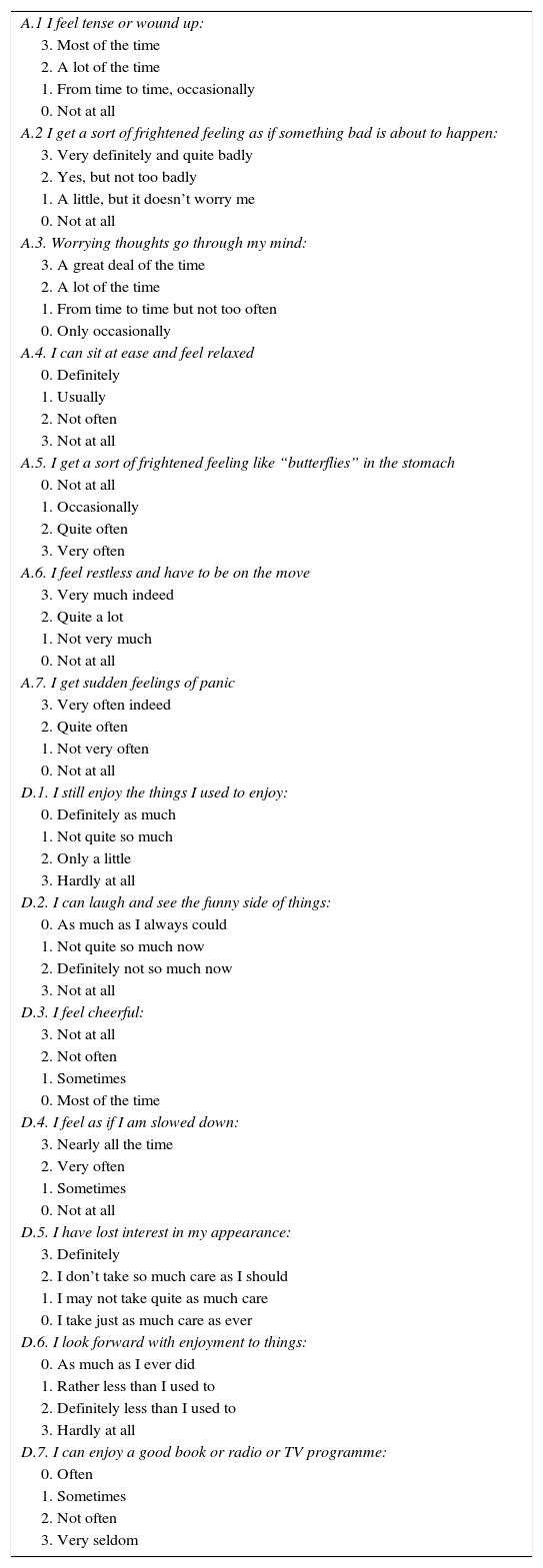

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (Table 5)The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) consists of 14 items that can be used to assess both anxiety and depression in primary care and other nonpsychiatric settings.15,16 It is the most widely used scale in research by nonpsychiatric specialists. The HADS addresses psychological aspects of anxiety and depression. The fact that it does not assess somatic symptoms (insomnia, fatigue, loss of appetite, etc.) prevents diagnostic errors when used in individuals with medical conditions (Table 5).

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).

| A.1 I feel tense or wound up: |

| 3. Most of the time |

| 2. A lot of the time |

| 1. From time to time, occasionally |

| 0. Not at all |

| A.2 I get a sort of frightened feeling as if something bad is about to happen: |

| 3. Very definitely and quite badly |

| 2. Yes, but not too badly |

| 1. A little, but it doesn’t worry me |

| 0. Not at all |

| A.3. Worrying thoughts go through my mind: |

| 3. A great deal of the time |

| 2. A lot of the time |

| 1. From time to time but not too often |

| 0. Only occasionally |

| A.4. I can sit at ease and feel relaxed |

| 0. Definitely |

| 1. Usually |

| 2. Not often |

| 3. Not at all |

| A.5. I get a sort of frightened feeling like “butterflies” in the stomach |

| 0. Not at all |

| 1. Occasionally |

| 2. Quite often |

| 3. Very often |

| A.6. I feel restless and have to be on the move |

| 3. Very much indeed |

| 2. Quite a lot |

| 1. Not very much |

| 0. Not at all |

| A.7. I get sudden feelings of panic |

| 3. Very often indeed |

| 2. Quite often |

| 1. Not very often |

| 0. Not at all |

| D.1. I still enjoy the things I used to enjoy: |

| 0. Definitely as much |

| 1. Not quite so much |

| 2. Only a little |

| 3. Hardly at all |

| D.2. I can laugh and see the funny side of things: |

| 0. As much as I always could |

| 1. Not quite so much now |

| 2. Definitely not so much now |

| 3. Not at all |

| D.3. I feel cheerful: |

| 3. Not at all |

| 2. Not often |

| 1. Sometimes |

| 0. Most of the time |

| D.4. I feel as if I am slowed down: |

| 3. Nearly all the time |

| 2. Very often |

| 1. Sometimes |

| 0. Not at all |

| D.5. I have lost interest in my appearance: |

| 3. Definitely |

| 2. I don’t take so much care as I should |

| 1. I may not take quite as much care |

| 0. I take just as much care as ever |

| D.6. I look forward with enjoyment to things: |

| 0. As much as I ever did |

| 1. Rather less than I used to |

| 2. Definitely less than I used to |

| 3. Hardly at all |

| D.7. I can enjoy a good book or radio or TV programme: |

| 0. Often |

| 1. Sometimes |

| 2. Not often |

| 3. Very seldom |

Read each question and underline the response that you feel describes your own emotional state over the last week. Don’t think about each response for too long. In this questionnaire, spontaneous responses are better than the ones that you think about a lot.

The HADS uses a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 3, which patients use to describe how they have felt over the last week. This short scale consists of 2 subscales comprising 7 interspersed items each. The depression subscale focuses on anhedonia as a core symptom of depression, as this largely differentiates depression from anxiety. For both the anxiety and depression subscales, a score of 0 to 7 is considered normal, while a score of 8 to 10 indicates probable anxiety or depression and one of 11 or higher indicates anxiety or depressive disorder (depending on the subscale used).

Criteria for Referral from DermatologyDermatologists should take the following points into account when deciding whether or not to administer tests for the early detection of anxiety or depression:

- -

Inclusion of a recommendation for testing in clinical guidelines for dermatologic conditions of certain severity known to cause psychological distress (e.g., moderate to intense psoriasis, glossodynia, acne).

- -

Appearance of isolated psychological symptoms that may cause the dermatologist to suspect an anxiety or depressive disorder; examples are anhedonia (inability to experience pleasure in situations which the patient used to enjoy), chronic insomnia, fatigue, loss of appetite or weight, frequent crying, etc.

- -

Recent changes in personality or actions that raise suspicion of psychological distress.

The criteria for referring a patient to mental health services are the same in dermatology as in other nonpsychiatric specialties.17 As a general rule, any patient suspected of having a psychiatric disorder other than anxiety and depression should be referred for evaluation. Examples are psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia or paranoia (characterized by hallucinations and delirium), or severe disorders, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder (obsession or recurrent ideas or impulses, or acts that the person cannot avoid) and somatic symptom disorders (complaints of bodily symptoms not caused by a somatic disease). Although anxiety and depression can be treated by dermatologists and other nonpsychiatric specialists in most cases, there are certain situations in which referral to mental health services is advised. The most important of these are summarized below:

- -

Suicidal ideation. Suicidal ideation is a serious complication in psychiatry. If a patient reports having thought about committing suicide and about how to this, they should be referred to the mental health service. Suicidal thoughts are not the same as thinking about death, which is very common in psychiatric patients and does not indicate a risk of suicide. Suicidal ideation can be assessed through questions such as “Have you ever thought that it wasn’t worth continuing, that it wasn’t worth going on?” If the patient answers affirmatively, it can be considered that there is a risk of suicidal ideation.

- -

Associated personality disorder. Personality disorders are mental disorders characterized by long-term patterns of behaviors, emotions, and thoughts that are very different to what is culturally expected. These behaviors interfere with the person's ability to engage in interpersonal relationships, work, and other domains of life. They include hypochondriacal traits, odd or magical thinking or behavior, strong emotional dependence, etc.

- -

Trauma. Extreme psychological situations (e.g., physical abuse, rape, war, violence) can cause psychiatric disturbances that require very specific psychotherapy.

- -

Severe comorbidity. The presence of other serious medical illnesses associated with a high risk of psychological distress (e.g., cancer, human immunodeficiency virus infection, or kidney or liver failure) can complicate the pharmacological treatment of anxiety and depression, as certain drugs cannot be prescribed, and generally speaking, care must be taken regarding drug-to-drug interactions and contraindications.

- -

Patient request. Serious consideration must be given to spontaneous requests from patients asking to be referred to mental health services.

- -

Dermatologist's decision. Uncertainty or discomfort on the part of the dermatologist in terms of managing the psychological aspects of a patient's condition are sufficient grounds for referral.

- -

Recurrent depressive disorder. This disorder is characterized by the repeated occurrence of depressive episodes, with characteristics of mild, moderate, or severe depression.

- -

Associated psychotic symptoms. Psychosis is a loss of contact with reality. It usually involves 1) delirium (false beliefs about what is happening or who one is) and 2) hallucinations (seeing or hearing things that do not exist).

- -

Suspicion of bipolar disorder. A person with bipolar disorder experiences periods of depression and other periods in which they are extremely happy or ill-humored and irritable. In addition to these mood swings, the person also displays extreme changes in energy and activity.

- -

Ineffective pharmacological treatment. Patients who do not respond to pharmacological treatment for anxiety or depression should be considered candidates for referral.

The following basic recommendations should be taken into account when referring a dermatologic patient to mental health or other services:

- -

Do not abandon the patient. The patient must not feel that they are a nuisance and that by referring them to another specialist, we are getting rid of them. A patient will be more willing to be referred if we explain that certain aspects of their disease (i.e., psychologic aspects) will be treated better by a specialist, but it is also important to stress that we will continue to see them regularly to monitor their dermatologic condition. It is in fact a good idea at this stage to schedule an appointment to see the patient following their mental health evaluation.

- -

Do not create expectations. Do not say what the other specialists are going to do or not do, or what they are going to say, and do not talk about possible results (e.g., “they will cure you there”), because this may cause false expectations.

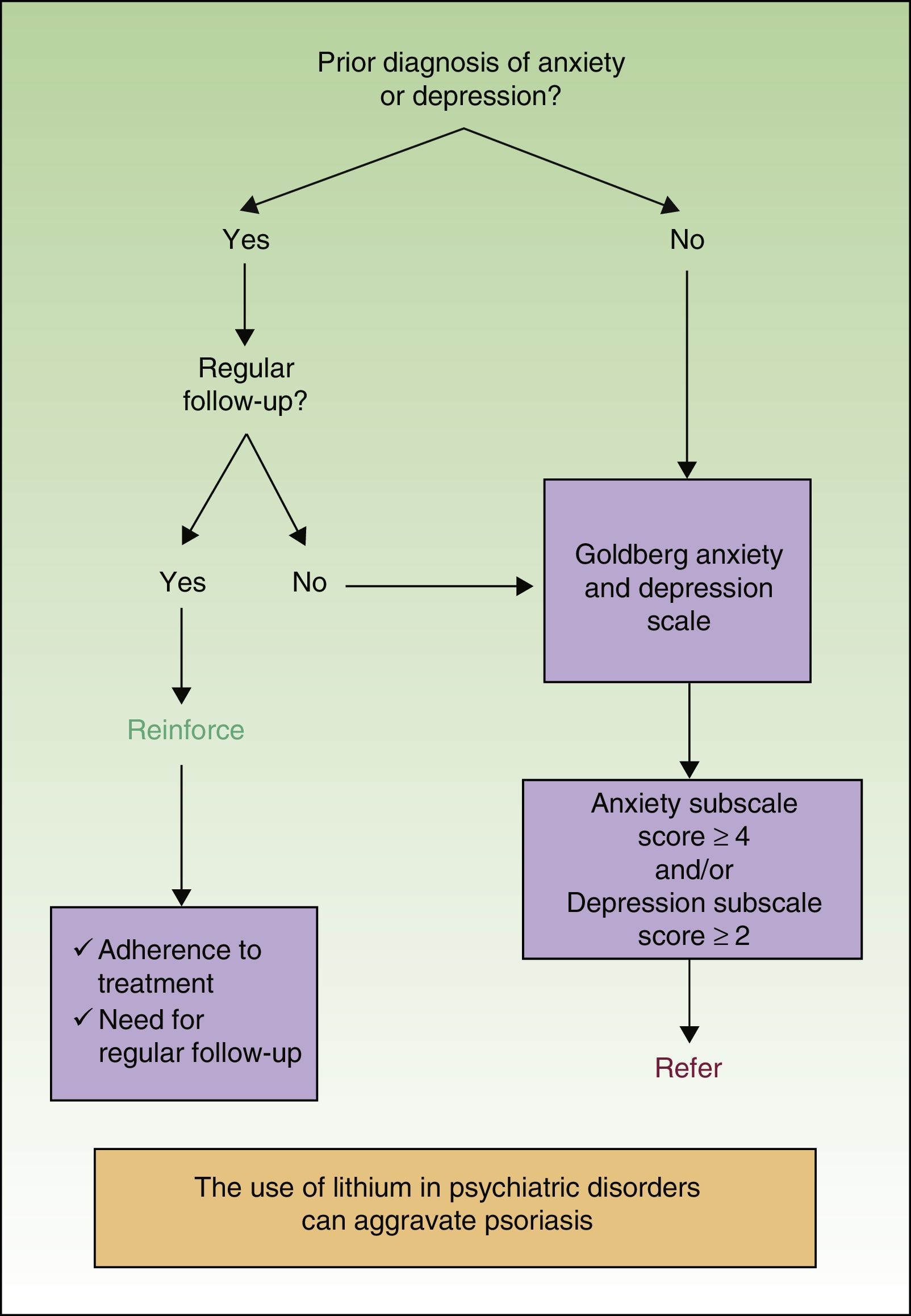

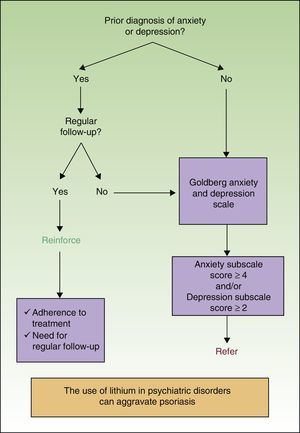

The clinical practice guidelines for an integrated approach to comorbidity in patients with psoriasis18 includes an algorithm for managing anxiety and depression in dermatologic patients (Fig. 1).19 When anxiety and/or depression are suspected, the guidelines recommend first administering the GADS, as this is one of the simplest, shortest, and easiest-to-administer tools for nonpsychiatric specialists.

Algorithm for managing anxiety and depression in dermatology.

Source: Dauden et al.19

The guidelines also recommend that patients who answer “yes” to 4 or more questions on the anxiety subscale and/or 2 or more questions on the depression subscale should be referred for evaluation.

Attention is also drawn to the importance of encouraging patients with a previous diagnosis of anxiety and/or depression who are already being seen regularly by their doctor or specialist to continue with their treatment and visits. Finally, patients not undergoing regular follow-up should be referred.

Summary of Key Points- -

Dermatologists play a key role in the prognosis of patients with mental illness through prevention, detection, and early treatment.

- -

Psychological tests measures characteristics not people. They are useful for transforming abstract psychological constructs into an objective, numerical language.

- -

The use of tests for the early detection of mental disorders in dermatology is key for the prevention and prognosis of these disorders.

- -

It is essential to know when to refer a dermatology patient for psychiatric evaluation. Such decisions can be aided by clinical practice guidelines.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: García-Campayo J, Pérez-Yus MC, García-Bustinduy M, Daudén E. Detección precoz de la enfermedad psicoemocional en dermatología. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:294–300.