Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis (NEH) is a nonspecific clinicopathological reaction pattern, classified as a neutrophilic dermatosis, that usually develops in patients receiving chemotherapy for a hematologic malignancy. More rarely, it has been reported in association with infectious agents such as Serratia and Enterobacter species, Staphylococcus aureus, and human immunodeficiency virus.

We describe 3 cases of infectious eccrine hidradenitis secondary to infection with Nocardia species, Mycobacterium chelonae, and S aureus.

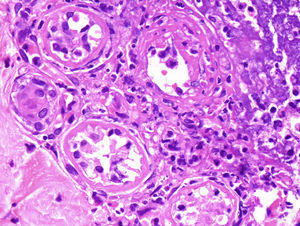

Histological findings revealed a dense infiltrate with perivascular and periductal neutrophils in the dermis. In the eccrine glands, there was vacuolar degeneration and necrosis of the epithelial cells.

Our cases support the assertion that NEH is a characteristic cutaneous response to nonspecific stimuli. Clinical and histopathological findings of infectious and noninfectious NEH are generally indistinguishable and when NEH is suspected, the possibility of an infectious association must be investigated by skin tissue culture. In this article we also discuss differential diagnoses and review the literature.

La hidradenitis ecrina neutrofílica (HEN) es un patrón de reacción clínico-patológico inespecífico, que se ha clasificado como una dermatosis neutrofílica. Normalemente se ha descrito asociada a una enfermedad hematológica maligna. En algunas ocasiones se ha publicado la hidradenitis ecrina neutrofílica asociada a un microorganismo como Serratia, Enterobacter, Staphylococcus y VIH.

Nosotros describimos 3 casos de hidradenitis ecrina infecciosa secundarias a infecciones por Nocardia, Mycobacterium chelonae y Staphylococcus aureus. Las biopsias mostraron un denso infiltrado perivascular y periductal de neutrófilos en la dermis. En las glándulas ecrinas se apreciaba degeneración vacuolar y necrosis de las células epiteliales, predominantemente en la porción secretora.

Nuestros casos apoyan que la HEN es una respuesta cutánea característica a un estímulo inespecífico. Los hallazgos clínicos e histopatológicos de la HEN infecciosa o no infecciosa son generalmente indistinguibles. Cuando se considera un caso de HEN se debería investigar la posibilidad de una causa infecciosa y realizar un cultivo.

En este artículo hemos revisado los diagnósticos diferenciales clínicos e histopatológicos y la literatura publicada de esta entidad.

Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis (NEH) is a rare but distinctive condition, first described by Harrist et al.1 in 1982. It typically occurs in patients undergoing chemotherapy for malignant disease. It is an inflammatory dermatosis characterized by a neutrophilic infiltrate around and within the eccrine glands. There have also been very rare reports of NEH caused by infection, a condition that has been called infectious eccrine hidradenitis (IEH). Only 6 reports documenting the presence of an infectious pathogen at the site of the skin eruption have been reported in NEH,2–7 and there has also been a report of a case associated with streptococcal infectious endocarditis.8

This article describes the clinical and histopathological findings of 3 cases of IEH that add strength to the hypothesis that NEH is a clinicopathological reaction pattern caused by different factors.

Three cases of histologically confirmed NEH with an infectious origin were retrieved from our files. Clinical information was obtained from hospital records or clinicians, or via laboratory request forms. The following data were recorded for each patient when available: age, sex, clinical appearance and location of the lesions, clinical diagnosis, associated diseases, and follow-up. The biopsy samples had been routinely processed (fixed in 4% or 10% neutral buffered formalin) and paraffin-embedded material had been cut into 5-μm-thick sections and examined with hematoxylin–eosin, Ziehl-Neelsen, and Gram stains.

Case DescriptionsPatient 1, an 82-year-old man with disseminated nocardiosis involving the skin and the central nervous system, developed papular and nodular erythematous lesions on his arms, thighs, and ankles. Some of the lesions oozed a purulent exudate. The histopathological features were consistent with NEH and Nocardia species was isolated following culture of exudate. After diagnosis, despite specific antibiotic treatment, the patient's condition worsened, with progressive central nervous system impairment, and he died.

Patient 2 was a 37-year-old man with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and Burkitt lymphoma in complete remission (nonrecent chemotherapy). He had multiple crops of papules on the legs and soles of the feet (Fig. 1), histopathological findings consistent with NEH, and a positive lesion culture for Mycobacterium chelonae. The recurrent skin lesions disappeared after 12 months of treatment with clarithromycin, ciprofloxacin, and cotrimoxazole. There have been no known recurrences.

Patient 3 was a previously healthy 57-year-old man with concomitant endocarditis and meningitis. He developed papules on the abdominal skin and had histopathologic findings of NEH and a lesion culture that was positive for Staphylococcus aureus. He died of septic complications.

Table 1 summarizes the clinical data of the 3 patients and the cases described in the literature.

Clinical Data of 3 Patients With Infectious Neutrophilic Eccrine Hidradenitis and Summary of Cases Described in the Literature.

| Case | Sex | Age, y/o | Clinical Features | Lesion Site | Pathogens | Associated Diseases or Findings | Follow-up | |

| 1 | Case 1 (present series) | M | 82 | Papules, nodules | Arms, thigh, ankles | Nocardia species | Demyelinating neuropathy | Deceased |

| 2 | Case 2 (present series) | M | 37 | Papules | Legs, soles of feet | Mycobacterium chelonae | Diabetes, HIV infection, lymphoma | Resolution of lesions |

| 3 | Case 3 (present series) | M | 57 | Papules | Abdominal skin | Staphylococcus aureus | None | Deceased |

| 4 | Oono et al.2 | F | 71 | Papules, small pustules | Chest, upper back, arms | Gram-positive cocci | Bullous pemphigoid | ND |

| 5 | Antonovich et al.3 | F | 83 | Plaques, nodules | Thigh | Nocardia species | COPD, mitral valve prolapse, breast and endometrial cancer | Resolution of lesions |

| 6 | Combemale et al.4 | M | 31 | Papules | Lower legs, thigh, abdomen | Serratia marcescens | Low-grade spinal ependymoma | ND |

| 7 | Taira et al.5 | M | 47 | Papules | Left wrist | S aureus | Heart transplant | Resolution of lesions |

| 8 | Allegue et al.6 | M | 47 | Papules, pustules | Forearm, thigh, abdomen, ankle | Enterobacter cloacae | None | Resolution of lesions |

| 9 | Moreno et al.7 | M | 48 | Papules | Arms, legs | Serratia species | Renal failure and hemodialysis | ND |

Abbreviations: COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ND, not described.

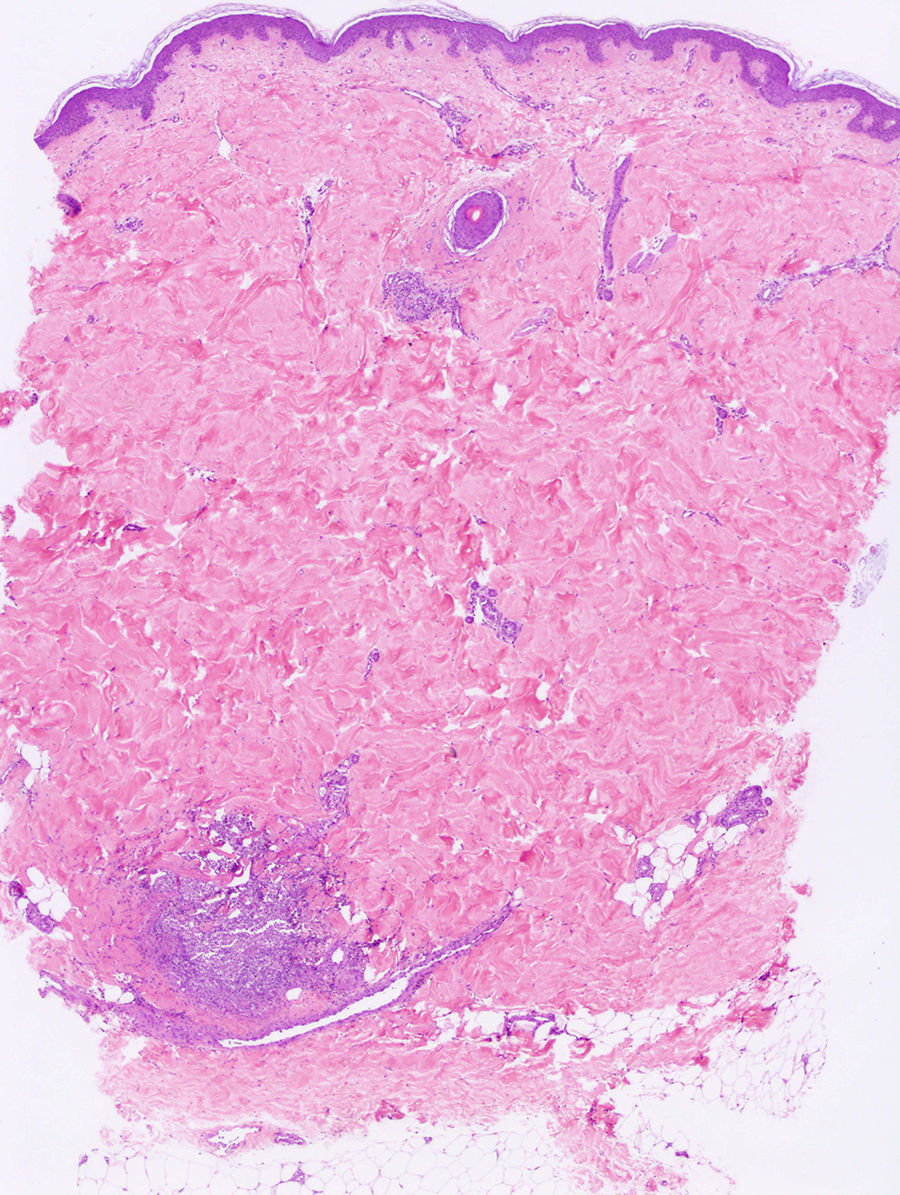

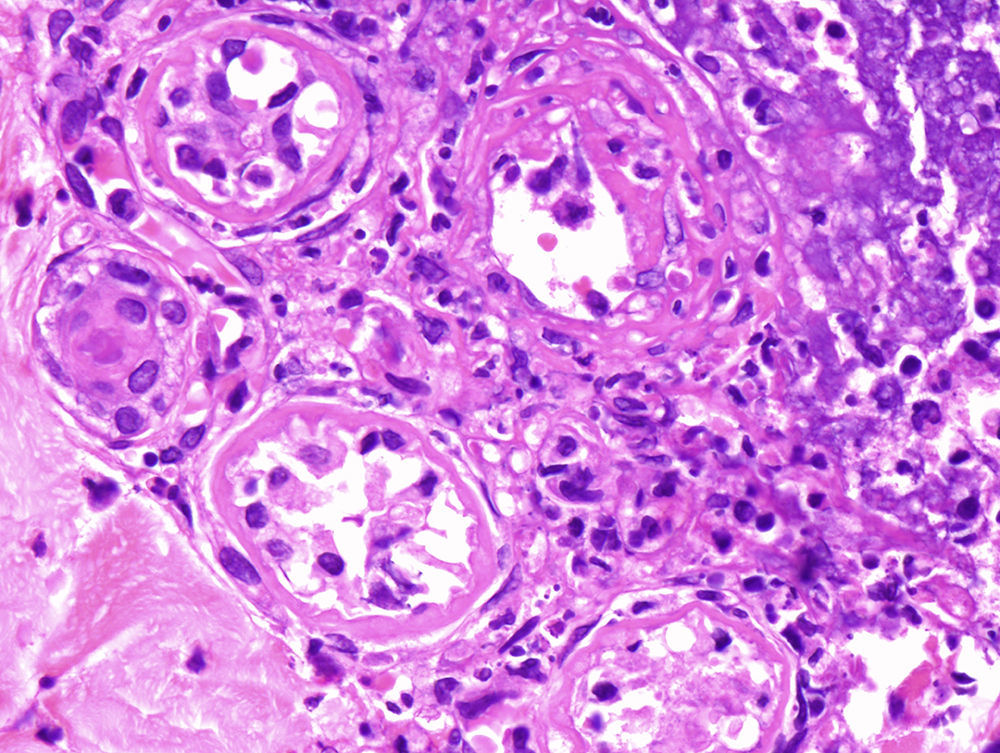

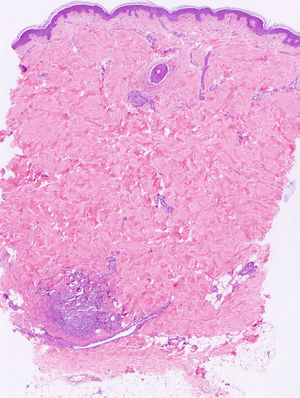

Punch biopsies and microscopic examination revealed similar features in the 3 cases. The epidermis was essentially normal. There was a dense perivascular and periductal infiltrate of neutrophils in the dermis with duct infiltration. In the eccrine glands, there was vacuolar degeneration and necrosis of the epithelial cells, predominantly in the secretory portion. Microabscess formation was also seen in this portion (Figs. 2 and 3). Vascular damage adjacent to neutrophilic abscesses was identified in patients 1 and 2. Ziehl-Neelsen and Gram staining revealed branching, beaded, filamentous, gram-positive bacteria with morphologic features of Nocardia species in patient 1 and gram-positive cocci in the lumen of the eccrine sweat gland coil in patient 3. In addition, tissue culture confirmed the presence of Nocardia species in patient 1, M. chelonae in patient 2, and S. aureus in patient 3.

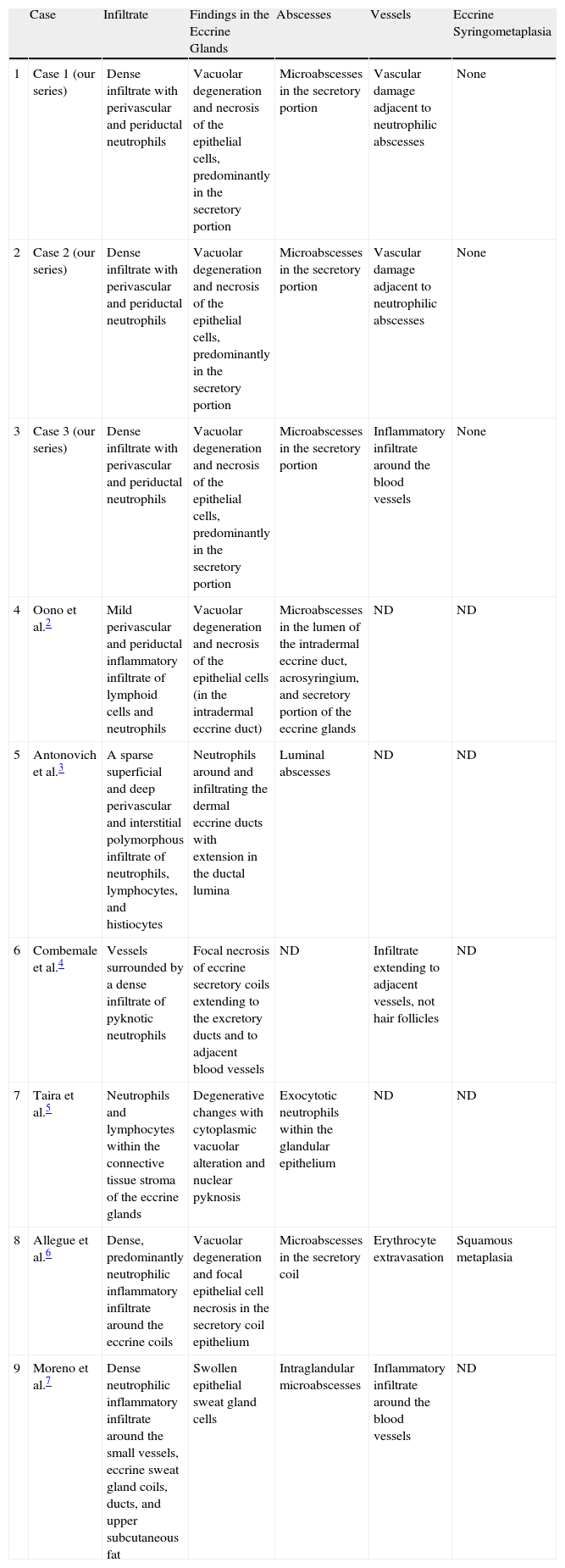

Table 2 summarizes the histopathological features of the 3 cases and the cases described in literature.

Summary of Histopathological Features of Infectious Neutrophilic Eccrine Hidradenitis in Our 3 Patients and the Cases Described in the Literature.

| Case | Infiltrate | Findings in the Eccrine Glands | Abscesses | Vessels | Eccrine Syringometaplasia | |

| 1 | Case 1 (our series) | Dense infiltrate with perivascular and periductal neutrophils | Vacuolar degeneration and necrosis of the epithelial cells, predominantly in the secretory portion | Microabscesses in the secretory portion | Vascular damage adjacent to neutrophilic abscesses | None |

| 2 | Case 2 (our series) | Dense infiltrate with perivascular and periductal neutrophils | Vacuolar degeneration and necrosis of the epithelial cells, predominantly in the secretory portion | Microabscesses in the secretory portion | Vascular damage adjacent to neutrophilic abscesses | None |

| 3 | Case 3 (our series) | Dense infiltrate with perivascular and periductal neutrophils | Vacuolar degeneration and necrosis of the epithelial cells, predominantly in the secretory portion | Microabscesses in the secretory portion | Inflammatory infiltrate around the blood vessels | None |

| 4 | Oono et al.2 | Mild perivascular and periductal inflammatory infiltrate of lymphoid cells and neutrophils | Vacuolar degeneration and necrosis of the epithelial cells (in the intradermal eccrine duct) | Microabscesses in the lumen of the intradermal eccrine duct, acrosyringium, and secretory portion of the eccrine glands | ND | ND |

| 5 | Antonovich et al.3 | A sparse superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial polymorphous infiltrate of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and histiocytes | Neutrophils around and infiltrating the dermal eccrine ducts with extension in the ductal lumina | Luminal abscesses | ND | ND |

| 6 | Combemale et al.4 | Vessels surrounded by a dense infiltrate of pyknotic neutrophils | Focal necrosis of eccrine secretory coils extending to the excretory ducts and to adjacent blood vessels | ND | Infiltrate extending to adjacent vessels, not hair follicles | ND |

| 7 | Taira et al.5 | Neutrophils and lymphocytes within the connective tissue stroma of the eccrine glands | Degenerative changes with cytoplasmic vacuolar alteration and nuclear pyknosis | Exocytotic neutrophils within the glandular epithelium | ND | ND |

| 8 | Allegue et al.6 | Dense, predominantly neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate around the eccrine coils | Vacuolar degeneration and focal epithelial cell necrosis in the secretory coil epithelium | Microabscesses in the secretory coil | Erythrocyte extravasation | Squamous metaplasia |

| 9 | Moreno et al.7 | Dense neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate around the small vessels, eccrine sweat gland coils, ducts, and upper subcutaneous fat | Swollen epithelial sweat gland cells | Intraglandular microabscesses | Inflammatory infiltrate around the blood vessels | ND |

Abbreviation: ND, not described.

Although NEH usually affects patients with hematologic malignancies undergoing chemotherapy,1,9 this neutrophilic dermatosis has also been reported in association with nonchemotherapeutic agents,10,11 in immunocompromised persons,12,13 and in patients who later develop leukemia.14,15 It has only occasionally been associated with infection.

Clinical manifestations include erythematous papules, small nodules, plaques, pustules, purpura, and urticaria. The presence of an infectious pathogen at the site of the skin eruption has only been reported in 6 cases2–7 and there has also been a report of NEH occurring in association with streptococcal infectious endocarditis with a negative skin tissue culture and a positive blood culture.8 IEH is rare and, as occurred in our 3 cases, most of the cases reported have documented an infectious pathogen at the site of the skin eruption as well as a concomitant and/or associated infectious disease.

IEH was first described in 1985 by Moreno et al.7 in a patient with chronic renal failure on hemodialysis who experienced recurrent crops of erythematous papules on his extremities over the course of 3 years. The authors suggested that altered immunity might have facilitated infection by Serratia species, a common cause of nosocomial infection. There has also been another report of Serratia-related IEH in a patient previously operated on for ependymoma, with recurrence of the disease on 3 occasions.4 The same bacterium (Serratia marcescens) was isolated on each occasion and the disease remitted after antibiotic therapy. IEH has since been reported in an otherwise healthy man who had not received chemotherapy.6 In that case, the infectious agent was Enterobacter cloacae. Gram-positive cocci were found in the lesional eccrine duct in another case2 and there has also been a report of Staphylococcus aureus infection in an immunosuppressed man on ciclosporin therapy following a heart transplant.5

To the best of our knowledge, only 1 case of IEH with Nocardia asteroides infection has been reported.3 The patient had multiple, tender, erythematous plaques and nodules on her right thigh and the infectious agent was detected histologically in the eccrine ductal epithelium and subsequently identified by tissue culture. She was treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, with complete resolution of the skin lesions in 3 weeks. In our case of IEH secondary to Nocardia species, the patient developed nodular erythematous lesions, some of which oozed a purulent exudate, on the arms, thighs, and ankles. Despite specific antibiotic treatment with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and supportive care, the patient's condition worsened and he died following progressive central nervous system impairment.

We have described 3 cases of IEH secondary to Nocardia species, M chelonae, and S aureus. In each of the cases, the bacteria were isolated by skin lesion tissue culture. The clinical manifestations of IEH include infiltrated, erythematous papules, small nodules, plaques, pustules, purpura, and urticaria and the presentation is similar to that seen in NEH caused by other factors.

Although not obviously within the category of IEH, HIV infection has been associated with the development of classic NEH.12,13 The eruptions may have been the result of HIV therapy or infectious pathogens, although repeated blood and skin cultures were negative. One of our patients (case 2) also had HIV infection. He had recurrent eruptions and was not receiving antiviral therapy at the time of these eruptions. M. chelonae was isolated from the skin lesions.

In addition to the characteristic histological features reported in the literature, in our 3 cases we also saw considerable vascular damage, adjacent to neutrophilic abscesses in patients 1 and 2.

Histopathological findings of infectious and noninfectious NEH are generally indistinguishable and when NEH is suspected, the possibility of an infectious origin must be considered and investigated by skin tissue culture. Although the absence of metaplasia might be taken as a clue to an infectious origin, we found the presence or absence of syringometaplasia to have no bearing on either of our cases or on those in the literature reviewed.2–7 Further specific studies are necessary to investigate the significance and etiology of metaplasia in NEH.

The final outcomes in our cases support the assertion that NEH is a characteristic cutaneous response to nonspecific stimuli and should be included in the differential diagnosis of a spectrum of clinical presentations. An infectious cause should be ruled out with appropriate cultures in all cases of NEH. In case 1, our patient developed secondary cerebral abscesses, probably caused by Nocardia species, and died. In case 3, the patient developed an infectious endocarditis with staphylococcal sepsis and also died. We were unable to assess the outcome of the skin lesions after the introduction of adequate treatment in these 2 cases. Patient 2, however, was treated with antibiotics for 12 months and experienced complete resolution of skin lesions.

We agree with the previously published observation that it is not possible to distinguish IEH from noninfectious cases on the basis of clinical and microscopic findings.7 In particular, the case of our second patient, who had HIV infection and no other manifestations of infectious disease, shows how important it is to rule out the presence of an infectious agent with appropriate cultures in all cases of NEH.

Even though infectious etiology is very rare in NEH, we believe that it should be explored in patients with histopathological findings of NEH who are at risk for nosocomial infections, as appropriate antibiotic treatment could be beneficial. Finally, NEH should be considered in the differential diagnosis of a wide variety of clinical settings and histopathological findings.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of Human and Animal SubjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of DataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work centre on the publication of patient data and that all the patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their informed consent in writing to participate in this study.

Right to Privacy and Informed ConsentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article and the author for correspondence is in possession of this documentation.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.