Atopic dermatitis is the most common inflammatory skin disease and up to 20% of cases can be classified as moderate to severe. Our understanding of the pathogenesis of this disease has improved in recent years. The process is primarily driven by the Th2 pathway, but with significant contributions from the Th22 pathway, the Th1 and Th17 axes, epidermal barrier dysfunction, pruritus, and JAK/STAT signaling. Advances in our understanding of the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis have led to the development of new systemic treatments. Of particular note are biologic agents targeting IL-4 and IL-13 (e. g., dupilumab, tralokinumab, and lebrikizumab) and small molecules, such as JAK inhibitors (e. g., baricitinib, upadacitinib, and abrocitinib). Novel topical treatments include phosphodiesterase 4 and JAK/STAT inhibitors. In this article, we review the main advances in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Characterization of clinical and molecular phenotypes with a key pathogenic role is essential for driving these advances.

La dermatitis atópica (DA) es la dermatosis inflamatoria más frecuente y hasta un 20% de los casos pueden clasificarse como moderados a graves. En los últimos años se ha producido un avance en el conocimiento de la patogenia, centrada en la vía Th2, pero con una participación marcada de la vía Th22 y de los ejes Th1 y Th17, de la disfunción de barrera epidérmica, el prurito,y la señalización JAK/STAT. Este progreso ha condicionado el desarrollo de nuevas terapias sistémicas, entre las que destacan fármacos biológicos dirigidos frente a la IL-4/13, como dupilumab, tralokinumab y lebrikizumab, pero también moléculas pequeñas, como los inhibidores de JAK, entre los que se incluyen baricitinib, upadicitinib y abrocitinib. Entre las innovaciones en los tratamientos tópicos se incluyen los inhibidores de la PDE4 y de JAK/STAT. Este artículo repasa los principales avances terapéuticos en DA, para los que son esenciales la caracterización de los subtipos clínicos y moleculares clave en su patogénesis.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is the most common inflammatory skin disease, with an estimated prevalence of 10% to 15% in children and 2% to 10% in adults in the Western population.1 Up to 20% of cases of AD can be classified as moderate or severe according to the different clinical measurement scales, the most widely used of which include the Investigator Global Assessment (IGA), the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), and the SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) scale.2,3

Clinically, there is a notable phenotypic variability driven by a complex interaction between genetics, immune function, and the environment. In recent years, a revolution in translational research has extended knowledge of pathogenesis of AD and led to the development of new molecules targeting key inflammatory elements of the disease.

This article reviews key aspects in the pathogenesis of the disease with potential application for therapeutic targets.

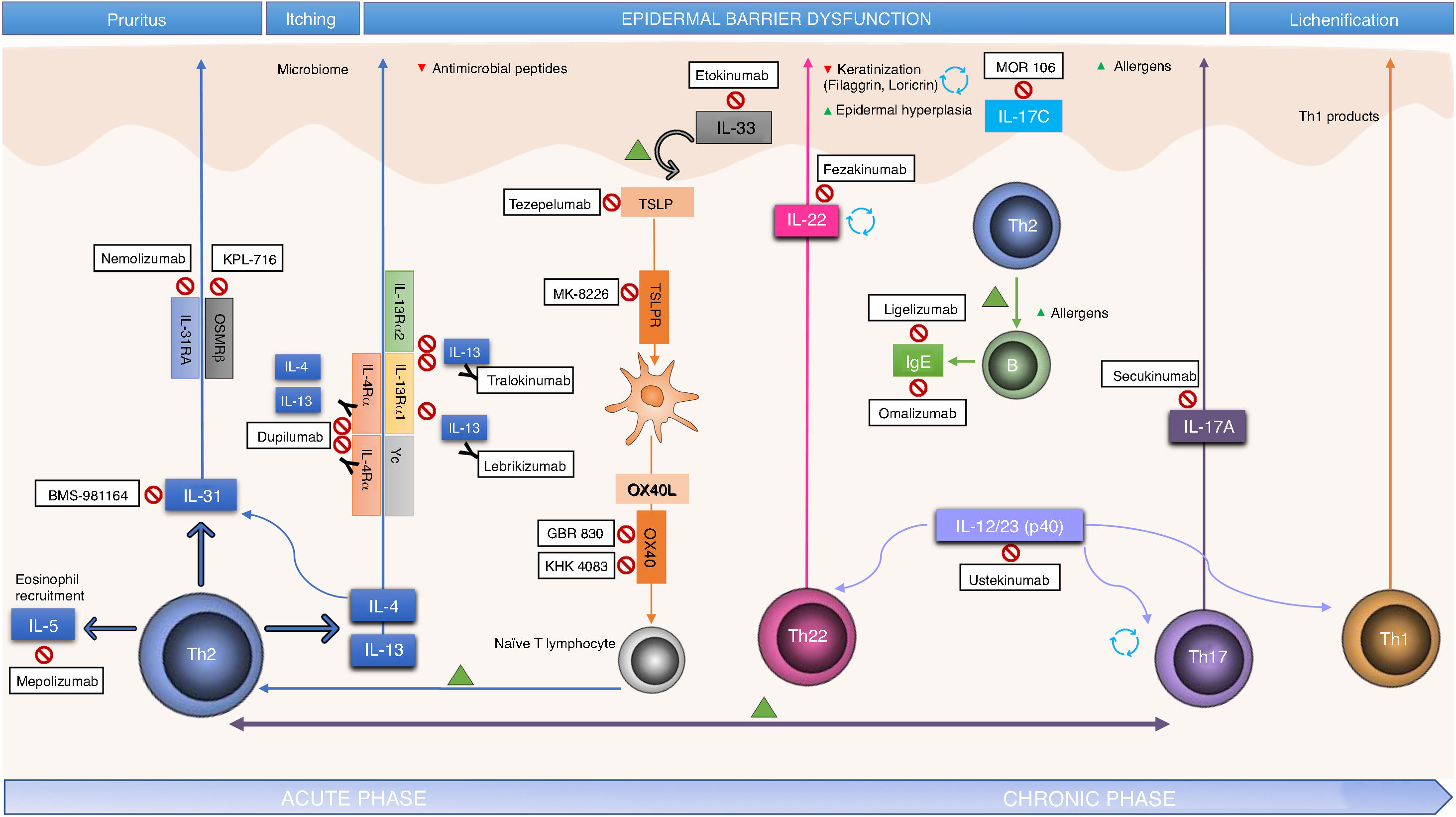

PathogenesisAD is considered a model of imbalance between response of T helper (Th) lymphocytes 1 and 2, with predominance of Th2 response. Th2 lymphocytes produce interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13, which inhibit the expression of filaggrin, thus establishing a relationship between immune dysfunction and disruption of barrier function typical in AD.4 In recent years, different translational studies have found the pathogenesis to pivot around Th2/Th22 response throughout the entire course of the disease, with a degree participation of Th17, and with an additional contribution from the Th1 axis in the chronic phase.5

However, the above framework is obviously a simplification, and the extent of the contribution of these responses is thought to vary according to disease subtype. Indeed, at least 3 immunological subtypes of AD have been characterized. In these subtypes, of note is the contribution of the Th17 response, even though substantial Th2/Th22 activation is maintained. These 3 subtypes are pediatric AD, which shows a higher participation of innate immunity, IL-9, and IL-33; the intrinsic variant (20% in adults), which typically presents with normal levels of IgE and without personal or family history of atopy; and finally the Asian phenotype, in which phenotypes with marked lichenification or psoriasis-like phenotypes predominate.6–8

There are also other potential participants in the pathogenic process. Thus, keratinocytes are an active element and produce cytokines, such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), able to induce expression of OX40?L through activation of immature dendritic cells, and IL-33, which induces expression of OX40?L through activation of type 2 innate lymphoid cells, and thus amplify Th2 response.9 These are the so called alarmins, an element of innate immunity and rapid and potent amplifiers of inflammatory response.

IL-4 and IL-13 are implicated in the synthesis of IL-31, a key participant in the induction of pruritus, and IL-5, which mediates recruitment of Th2 and eosinophils. In addition, pruritus leads to scratching, thus facilitating skin barrier dysfunction and colonization by Staphylococcus aureus, in turn perpetuating Th2 response and overexpression of IL-4, IL-13, and IL-22. Greater colonization is facilitated by the lower expression of antimicrobial peptides in lesioned skin and apparently healthy skin of patients with AD, also associated with the IL-4/IL-13 pathway (Fig. 1).4

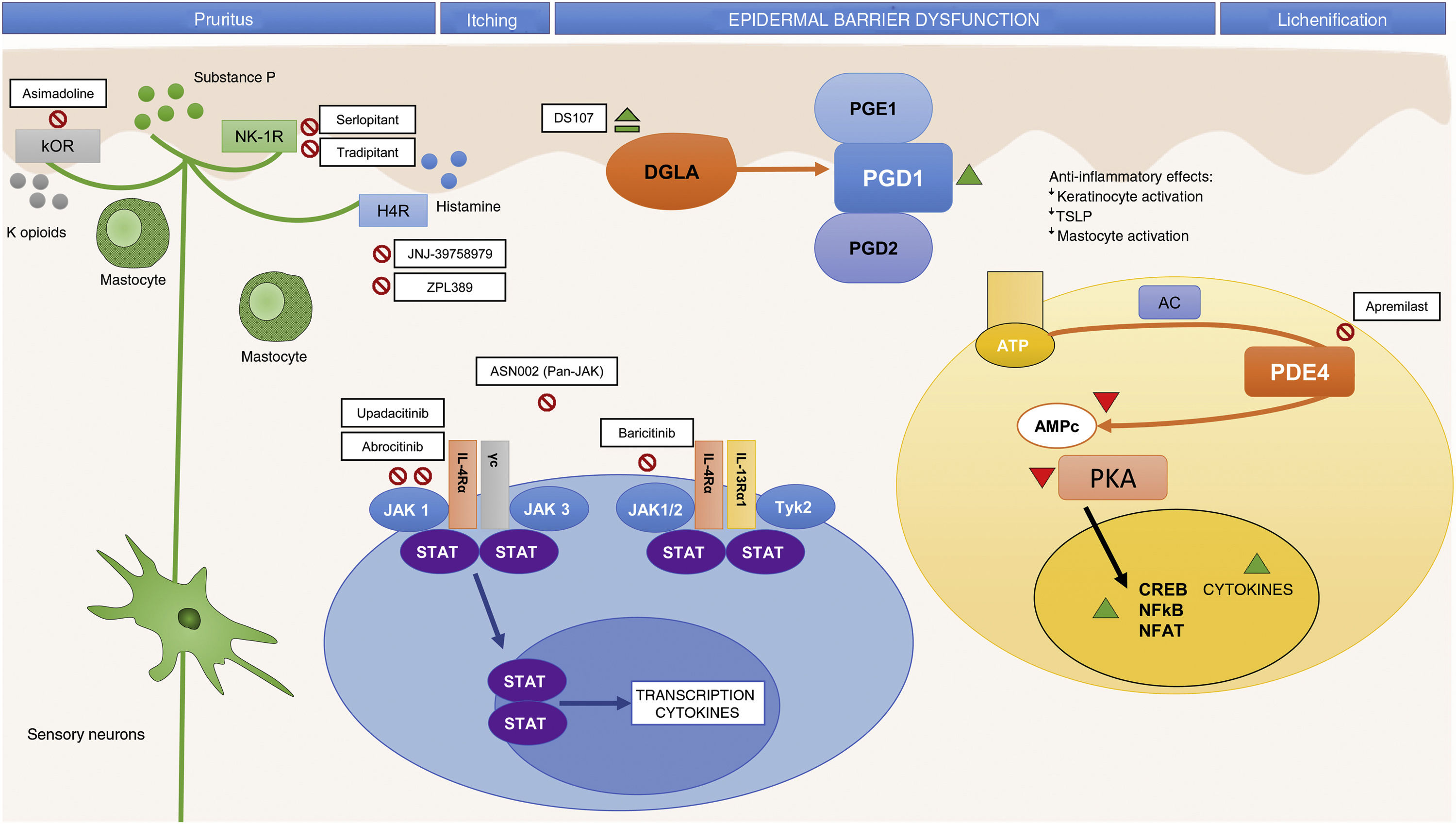

In addition to identifying key molecules in the pathogenesis of AD and, therefore, potential therapeutic targets for specific monoclonal antibodies, other molecules implicated throughout the inflammatory process have also been shown to be important. Thus, participation of the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT) pathway activated by IL-4 has also been studied in the immune dysregulation in AD. The JAK family is formed of 4 members (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and tyrosine kinase 2 [TYK2]) and, unlike alopecia areata or psoriasis, all 4 participate in AD.10 The different elements of this family form part of the numerous cytoplasmic IL receptors (Fig. 2). Inhibition of these molecules, therefore, would have an impact on numerous IL molecules implicated in Th2 response and eosinophil activation.11

Small Molecules and Specific Targets in the Pathogenesis of Atopic Dermatitis.

Abbreviations: AC, adenylyl cyclase; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate; CREB, cAMP response element-binging protein; DGLA, dihomo-?-linolenic acid; H4R, histamine 4 receptor; IL, interleukin; JAK, Janus kinase; ?OR, ?-opioid receptor; NF-?B, nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T-cells; NK-1R, neurokinin 1 receptor 1; PDE4, phosphodiesterase 4; PGD1, prostaglandin D1; PGD2, prostaglandin D2; PGE1, prostaglandin E1; PKA, protein kinase A; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; Th, T helper (lymphocyte); TSLP, thymic stromal lymphopoietin; TYK, tyrosine-kinase.

Better knowledge of the inflammatory pathways in AD as well as the pathways implicated in pruritus has led to the development of drugs that specifically target different cytokines as well as drugs with broad action targeting intracellular signaling, with an impact on the final production of different cytokines.

Systemic TreatmentsBiologic AgentsTh2 Cell Response Antagonists (IL-4 and IL-13)Blockade of the IL-4/IL-13 PathwayIL-4 and IL-13 are key elements in Th2 response. They trigger and control immune response in AD, such that specific antagonism of these cytokines has revolutionized therapeutics in this disease.

Dupilumab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits IL-4 and IL-13 by blocking the a subunit shared by the receptors of these IL molecules (IL-4Ra). In 2 phase iii randomized clinical trials (RCTs) (SOLO-1 and SOLO-2), with identical design in a total of 1379 adult patients with moderate to severe AD, dupilumab 300?mg every 2 weeks for 16 weeks was superior to placebo for the primary outcome measure (IGA of 0 or 1: 38% and 36% for dupilumab compared with 10% and 8% for placebo, respectively).12 Dupilumab was also superior for all secondary outcome measures (EASI-75, reduction of pruritus, symptoms of anxiety and depression, quality of life, and need for rescue medication) compared with placebo.12,13 Another phase iii RCT has also reported positive findings for dupilumab in combination with topical corticosteroids compared with placebo after 1?year of treatment (EASI-75; 65% for dupilumab 300?mg every 2 weeks compared with 22% for placebo; P?=?.001).14 Two recent meta-analyses show superior efficacy of treatment compared with placebo, with similar benefits for regimens of 300?mg weekly or every 2 weeks. The main specific adverse effects were local injection site reactions to the drug and conjuntivitis.15,16 At present, 2 phase iii RCTs in pediatric patients are in their final stages.17,18 In March of 2019, the FDA extended the approval for dupilumab to adolescent patients aged 12 to 17 years.

Tralokinumab is a monoclonal antibody targeting IL-13. It competitively blocks binding to 2 different receptors: the heterodimeric receptor composed of IL-4Ra (antagonized by dupilumab) and IL-13Ra1, and the decoy receptor IL-13Ra2, which mediates endogenous regulation of IL-13. This pathway enables assessment, therefore, of the extent to which inhibition of IL-4 may be redundant compared with IL-13 in the pathogenesis of the disease.19 In a phase iib RCT with 204 adults patient with moderate to severe AD, administration of tralokinumab at a dose of 300?mg every 2 weeks for 12 weeks achieved a decrease in EASI compared with placebo (mean baseline-adjusted change of -15.7% vs.?-?10.8; P?=?.011) and a higher percentage of patients had IGA 0 or 1 (26.7 vs. 11.8%). These results also show a high response to placebo, probably because of the concomitant use of topical corticosteroids in this RCT. There was also a significant improvement in SCORAD, the Dermatology Life Quality Index, and pruritus.20 Currently, phase iii RTCs are ongoing with tralokinumab in adults21 and adolescent patients.22

Lebrikizumab is another monoclonal antibody that targets IL-13. It binds to soluble IL-13 and inhibits binding to IL-4Ra.23 In a phase II RCT in 209 patients with moderate to severe AD, the group treated with lebrikizumab 125?mg every 4 weeks presented a greater percentage of EASI-50 responders than the placebo-treated group (82.4% vs. 62.3%; P?=?.026). Once again, there were notable responses in the placebo group, and these could be attributed to the concomitant use of topical corticosteroids.24 At present, a trial is ongoing to assess efficacy at a dose of 250?mg every 2 and 4 weeks.35

Specific blockade of IL-13 has also been assessed in asthma, with modest improvements for tralokinumab and lebrikizumab.26,27 As is the case for AD, response may be greater in those patients with higher concentrations of markers related to IL-13.20 However, RCTs with monotherapy are needed to assess the utility of blockade IL-13 on its own.

Blockade of Induction of Th2 Response: TSLP, OX40L, and IL-33The Th2 axis also includes the TSLP pathway, key in the interaction between the epidermis and innate and adaptive immune activation, given that inflammatory response leads to an allergic phenotype through activation of immature dendritic cells that express OX40?L, thus permitting polarization towards a Th2 response.28 Similarly, IL-33, produced by epithelial cells, can positively regulate the TSLP-dendritic cell-OX40?L axis, participating in the induction and maintenance of Th2 response.29,30 Inhibition of this pathway could be interesting from the point of view of early treatment, given its participation in initial Th2 response.

Tezepelumab is an anti-TSLP monoclonal antibody that was recently assessed in a phase IIa RCT without showing superior efficacy to placebo after 16 weeks.31 At present, another dose-finding RCT is ongoing with tezepelumab (NCT03809663). Another molecule, MK-8226, antagonist of the TSLP receptor, was assessed in a phase I RCT at different intravenous doses; a significant decrease in EASI at a dose of 3?mg/kg compared with placebo at 12 weeks was observed (10.20 vs. 0.38; P?=?.015).32

A monoclonal antibody against OX40, GBR 830, has been tested at an intravenous dose of 10?mg/kg/4 weeks for 2 months against placebo with positive results.33 At present, RCTs with another OX40 inhibitor, the KHK4093 molecule (NCT03096223 and NCT03703102), and with etokimab/ANB020, an anti-IL-33 antibody (NCT03533751) are ongoing.

Antagonism of Th22 ResponseTh22 lymphocytes are the main IL-22 producers and they participate in both acute and chronic forms of AD. IL-22 can increase barrier dysfunction, induce epidermal hyperplasia, and inhibit proteins that are important in normal keratinization, such as filaggrin.34

In a phase iia RCT, the use of fezakinumab (IVL-094), an anti-IL-22 agent, at a dose of 300?mg every 2 weeks achieved an improvement (measured as a decrease on SCORAD), although not a significant one, compared with placebo in patients with moderate to severe AD. The subanalysis of patients with severe AD did show significant differences in the reduction of Body Surface Area (BSA) and IGA.35 The benefit achieved with this drug might be limited to patients with worse response to Th2 blockade and with higher expression of Th22,36 although the evidence to date is limited.

Antagonism of Th17 ResponseAs mentioned earlier, in the chronic phase of AD and in certain groups of patients, Th2 and Th22 response is sustained, but there is parallel activation of the Th1/Th17 axis.37 Recently, blockade of IL-17A and IL-17C has been studied. Although data on inhibition of this axis in AD are still very premature, development in this area is of interest given the therapeutic potential in certain AD subphenotypes.

Secukinumab, a selective inhibitor of IL-17A, approved in psoriasis, has recently been studied in a phase II RCT in AD (NCT03533751), with the induction regimen used in psoriasis and with a maintenance dose of 300?mg/4 weeks or intensified to 300?mg/2 weeks. The results are pending publication.38

In addition, there are ongoing studies (NCT03568071, NCT03689829, NCT03864627) with an anti-IL-17C antibody, MOR106, which could mediate a decrease in levels of IgE and Th2 cytokines.39

Blockade of the IL-31 and OSMRß Pathway (Pruritus Signaling)IL-31 is a cytokine produced mainly by Th2 lymphocytes and is closely linked with pruritus in different cell types, including peripheral neurons.40,41 IL-31 binds to a heterodimeric receptor composed of an IL-31 receptor a (IL-31Ra) and oncastatin M receptor ß (OSMRß). Blockade, therefore, could also break the vicious circle of pruritus, scratching, and compromise of epidermal barrier function.

Nemolizumab blocks IL-31 receptor a (IL-31Ra). To date, a placebo-controlled phase II RCT in adults treated with nemolizumab (dose of 0.1?mg/kg, 0.5?mg/kg, and 2?mg/kg every 4 weeks for 12 weeks) showed decreases in pruritus; however, improvement on the clinical scales was not statistically significant.40,42 Nemolizumab could be effective in reducing pruritus, as well as improving daily activities and work productivity,43 with an acceptable safety profile. At present, a dose-finding RCT is pending completion (NCT03100344).

The phase I RCT (NCT01614756) that investigated the use of an anti-IL-31 agent (BMS-981164) was terminated early and the results were not published. It is therefore unknown whether the effects of blockade of IL-31 would be limited to an effect on the symptoms of pruritus, given that there was no significant improvement in the skin inflammation outcome measures.

In addition, a phase Ia/Ib RCT has been conducted with KPL-716, an anti-OSMRß antibody that has demonstrated an improvement in EASI and in the pruritus scales compared with placebo.44

IgE AntagonismOmalizumab, an anti-IgE agent approved for the treatment of asthma, has been assessed in a meta-analysis; no evidence of overall effectiveness in adults with AD was found.45 Its use in pediatric patients is being assessed (NCT02300701).

Small MoleculesThe group of small molecules includes orally administered agents that generate a broad reduction, although less specific, in the release of mediators. This strategy has advantages in AD as, unlike psoriasis, there is no evidence of a key molecule involved in the pathogenesis of the disease. However, the lower specificity could be associated with potential issues with safety.

Inhibition of the JAK-STAT Signaling PathwayAt present, there are 4 orally administered JAK inhibitors under study.11 Baricitinib antagonizes JAK 1 (associated with modulation of the cytokines IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, IL-13, IL-31, and IFN-?) and JAK2 (which modulates the cytokines IL-5, IL-6, IL-23, IL-31, and IFN-?).11,46 In the first phase II RCT, administration of baricitinib at a dose of 4?mg a day orally in patients with moderate to severe AD was associated with a higher proportion of patients achieving EASI-50 compared with placebo (61% vs. 37%; P?=?.027) at 16 weeks, with good tolerability. Adverse effects reported included asymptomatic creatine kinase elevation, but there were no cases of thrombotic events or herpes zoster.47

Upadacitinib (ABT-494) and abrocitinib (PF-04965842) are selective JAK1 inhibitors, and early results with these agents are promising. A phase IIb RCT studied the use of upadacitinib at doses of 7.5, 15, and 30?mg compared with placebo for 16 weeks. The decrease in EASI compared with baseline was 71%, 62%, and 39% for the doses of 30, 15, and 7.5?mg, respectively. These improvements were similar to those obtained with dupilumab. At present, a phase III RCT is ongoing to evaluate the efficacy of upadacitinib in adults and adolescents (NCT03607422). Another phase IIb RCT assessed the use of abrocitinib at doses of 10, 30, 100 and 200?mg a day compared with placebo; the reductions in EASI were only significant for the 200?mg dose (82.6%; P? P?=?.009) compared with placebo (35.2%).46 Several phase III RCTs are ongoing with abrocitinib at doses of 100 and 200?mg compared with placebo (NCT03349060, NCT03575871, NCT03627767, and NCT03422822), as well as a phase III RCT with dupilumab as the comparator (NCT03720470). Finally, ASN002 is a dual inhibitor of the JAK and SYK pathways. PAN-JAK inhibition impacts the signaling of several cytokines implicated in AD (IL-4, IL-13, IL-31, and IL-33), whereas SYK inhibition suppresses signaling of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1ß, IL-10, and IL-17). In the first phase Ib RCT with ASN002, the percentage of patients who achieved EASI-50 at 28 days was higher than in placebo for doses of 40 and 80?mg.48

Currently, phase III RCTs are ongoing with these 4 drugs.

Phosphodiesterase 4 AntagonismRecently, treatment with phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4), administered both topically and orally, has been investigated. In AD, PDE4 activity in different inflammatory cells is increased compared with healthy skin. PDE degrades cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), a molecule that in normal conditions inhibits the production of several proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-4, IL-32, and PGE-2. PDE4 antagonism has a broad and nonspecific action, as it elevates intracellular cAMP and enables a reduction in cytokine and chemokine release.49

In a phase II study, apremilast at a dose of 40?mg/12?hours achieved a greater reduction in EASI than placebo (31.57% vs. 10.98%; P?=?.034). However, there were no statistically significant differences in EASI-50 or pruritus.50 At present, there are no new RCTs with apremilast in AD.

Histamine 4 Receptor AntagonismIn recent years, the role of histamine 4 receptor antagonism has been studied. This could in principle not only achieve an antipruritic effect but also an anti-inflammatory one, given that activation of the receptor in keratinocytes interferes in proliferation and barrier function.51

In a phase IIa RCT with the histamine 4 receptor antagonist, JNJ-39758979, there were significant differences in the reduction of pruritus but not EASI. However, this RCT was terminated early due to 2 cases of severe neutropenia.52 Recently, the results have been published of a phase II RCT with another histamine 4 receptor antagonist, ZPL-3893787, with significant reductions compared with placebo for EASI but no significant decrease in pruritus.53

Neurokinin 1 Receptor BlockadeSubstance P, a mediator in pruritus, binds mainly to the neurokinin 1 receptor, which is expressed both in the central nervous system and in skin. Thus, an oral neurokinin 1 receptor antagonist such as aprepitant could potentially improve pruritus.54 However, use of this agent in AD does not seem to be beneficial.55 Other inhibitors of the neurokinin 1 receptor, tradipitant and serlopitant, are under study, although also with modest results.

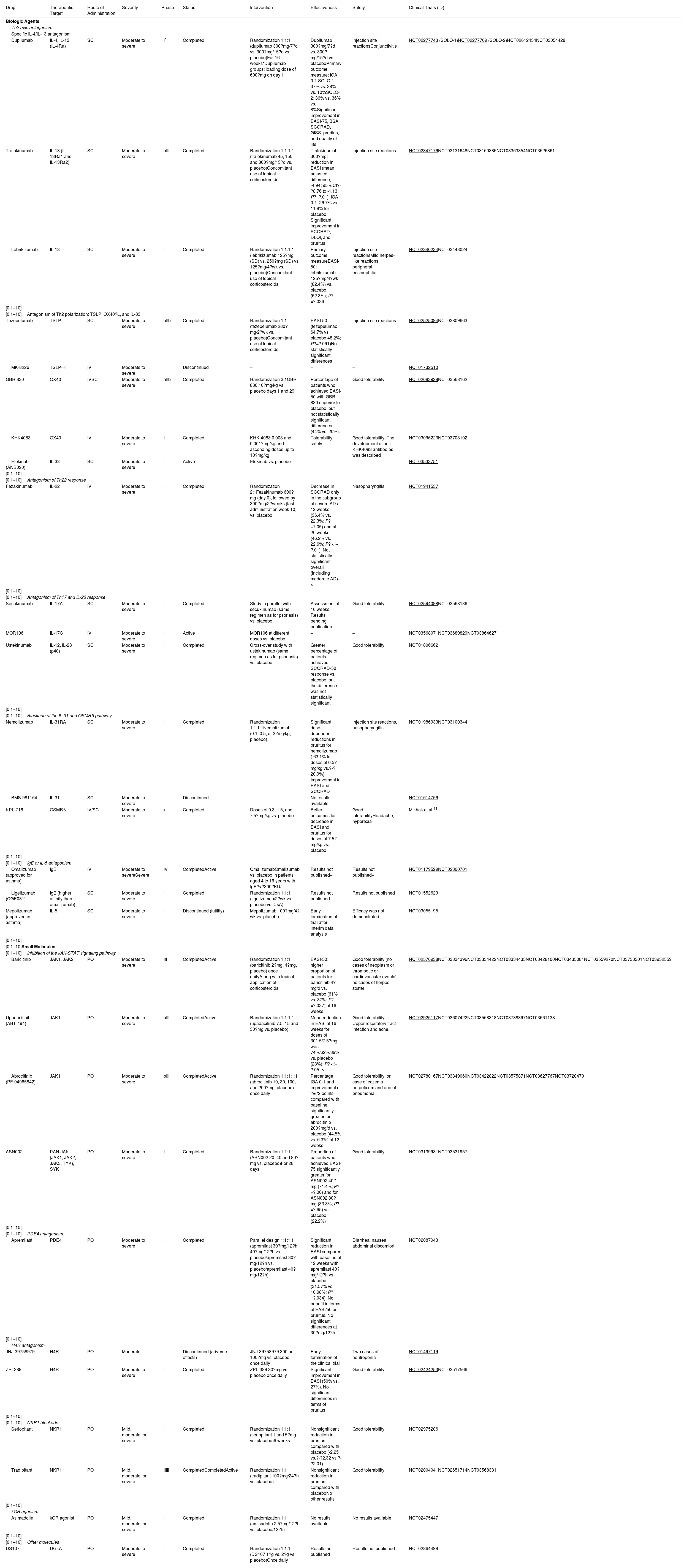

Table 1 summarizes the main RTCs with the new systemic treatments, and Figs. 1 and 2 show the main therapeutic targets.

Summary of the New Systemic Treatments in Development and in Phases of Investigation for Atopic Dermatitis.

| Drug | Therapeutic Target | Route of Administration | Severity | Phase | Status | Intervention | Effectiveness | Safety | Clinical Trials (ID) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biologic Agents | |||||||||

| Th2 axis antagonism | |||||||||

| Specific IL-4/IL-13 antagonism | |||||||||

| Dupilumab | IL-4, IL-13 (IL-4Ra) | SC | Moderate to severe | IIIa | Completed | Randomization 1:1:1 (dupilumab 300?mg/7?d vs. 300?mg/15?d vs. placebo)For 16 weeks*Dupilumab groups: loading dose of 600?mg on day 1 | Dupilumab 300?mg/7?d vs. 300?mg/15?d vs. placeboPrimary outcome measure: IGA 0-1 SOLO-1: 37% vs. 38% vs. 10%SOLO-2: 36% vs. 36% vs. 8%Significant improvement in EASI-75, BSA, SCORAD, GISS, pruritus, and quality of life | Injection site reactionsConjunctivitis | NCT02277743 (SOLO-1)NCT02277769 (SOLO-2)NCT02612454NCT03054428 |

| Tralokinumab | IL-13 (IL-13Ra1 and IL-13Ra2) | SC | Moderate to severe | IIbIII | Completed | Randomization 1:1:1:1 (tralokinumab 45, 150, and 300?mg/15?d vs. placebo)Concomitant use of topical corticosteroids | Tralokinumab 300?mg: reduction in EASI (mean adjusted difference, -4.94; 95% CI?-?8.76 to -1.13; P?=?.01). IGA 0-1: 26.7% vs. 11.8% for placebo. Significant improvement in SCORAD, DLQI, and pruritus | Injection site reactions | NCT02347176NCT03131648NCT03160885NCT03363854NCT03526861 |

| Lebrikizumab | IL-13 | SC | Moderate to severe | II | Completed | Randomization 1:1:1:1 (lebrikizumab 125?mg (SD) vs. 250?mg (SD) vs. 125?mg/4?wk vs. placebo)Concomitant use of topical corticosteroids | Primary outcome measureEASI-50: lebrikizumab 125?mg/4?wk (82.4%) vs. placebo (62.3%); P?=?.026 | Injection site reactionsMild herpes-like reactions, peripheral eosinophilia | NCT02340234NCT03443024 |

| [0,1–10] | |||||||||

| [0,1–10]Antagonism of Th2 polarization: TSLP, OX40?L, and IL-33 | |||||||||

| Tezepelumab | TSLP | SC | Moderate to severe | IIaIIb | Completed | Randomization 1:1 (tezepelumab 280?mg/2?wk vs. placebo)Concomitant use of topical corticosteroids | EASI-50 (tezepelumab 64.7% vs. placebo 48.2%; P?=?.091)No statistically significant differences | Injection site reactions | NCT02525094NCT03809663 |

| MK-8226 | TSLP-R | IV | Moderate to severe | I | Discontinued | – | – | – | NCT01732510 |

| GBR 830 | OX40 | IVSC | Moderate to severe | IIaIIb | Completed | Randomization 3:1GBR 830 10?mg/kg vs. placebo days 1 and 29 | Percentage of patients who achieved EASI-50 with GBR 830 superior to placebo, but not statistically significant differences (44% vs. 20%). | Good tolerability | NCT02683928NCT03568162 |

| KHK4083 | OX40 | IV | Moderate to severe | III | Completed | KHK-4083 0.003 and 0.001?mg/kg and ascending doses up to 10?mg/kg | Tolerability, safety | Good tolerability. The development of anti-KHK4083 antibodies was described | NCT03096223NCT03703102 |

| Etokinab (ANB020) | IL-33 | SC | Moderate to severe | II | Active | Etokinab vs. placebo | – | – | NCT03533751 |

| [0,1–10] | |||||||||

| [0,1–10]Antagonism of Th22 response | |||||||||

| Fezakinumab | IL-22 | IV | Moderate to severe | II | Completed | Randomization 2:1Fezakinumab 600?mg (day 0), followed by 300?mg/2?weeks (last administration week 10) vs. placebo | Decrease in SCORAD only in the subgroup of severe AD at 12 weeks (36.4% vs. 22.3%; P?=?.05) and at 20 weeks (46.2% vs. 22.6%; P? | Nasopharyngitis | NCT01941537 |

| [0,1–10] | |||||||||

| [0,1–10]Antagonism of Th17 and IL-23 response | |||||||||

| Secukinumab | IL-17A | SC | Moderate to severe | II | Completed | Study in parallel with secukinumab (same regimen as for psoriasis) vs. placebo | Assessment at 16 weeks. Results pending publication | Good tolerability | NCT02594098NCT03568136 |

| MOR106 | IL-17C | IV | Moderate to severe | II | Active | MOR106 at different doses vs. placebo | – | – | NCT03568071NCT03689829NCT03864627 |

| Ustekinumab | IL-12, IL-23 (p40) | SC | Moderate to severe | II | Completed | Cross-over study with ustekinumab (same regimen as for psoriasis) vs. placebo | Greater percentage of patients achieved SCORAD-50 response vs. placebo, but the difference was not statistically significant | Good tolerability | NCT01806662 |

| [0,1–10] | |||||||||

| [0,1–10]Blockade of the IL-31 and OSMRß pathway | |||||||||

| Nemolizumab | IL-31RA | SC | Moderate to severe | II | Completed | Randomization 1:1:1:1Nemolizumab (0.1, 0.5, or 2?mg/kg, placebo) | Significant dose-dependent reductions in pruritus for nemolizumab (-63.1% for doses of 0.5?mg/kg vs.?-?20.9%). Improvement in EASI and SCORAD | Injection site reactions, nasopharyngitis | NCT01986933NCT03100344 |

| BMS-981164 | IL-31 | SC | Moderate to severe | I | Discontinued | No results available | NCT01614756 | ||

| KPL-716 | OSMRß | IV/SC | Moderate to severe | Ia | Completed | Doses of 0.3, 1.5, and 7.5?mg/kg vs. placebo | Better outcomes for decrease in EASI and pruritus for doses of 7.5?mg/kg vs. placebo | Good tolerabilityHeadache, hyporexia | Mikhak et al.44 |

| [0,1–10] | |||||||||

| [0,1–10]IgE or IL-5 antagonism | |||||||||

| Omalizumab (approved for asthma) | IgE | IV | Moderate to severeSevere | IIIV | CompletedActive | OmalizumabOmalizumab vs. placebo in patients aged 4 to 19 years with IgE?>?300?KU/l | Results not published– | Results not published– | NCT01179529NCT02300701 |

| Ligelizumab (QGE031) | IgE (higher affinity than omalizumab) | SC | Moderate to severe | II | Completed | Randomization 1:1:1 (ligelizumab/2?wk vs. placebo vs. CsA) | Results not published | Results not published | NCT01552629 |

| Mepolizumab (approved in asthma) | IL-5 | SC | Moderate to severe | II | Discontinued (futility) | Mepolizumab 100?mg/4?wk vs. placebo | Early termination of trial after interim data analysis | Efficacy was not demonstrated. | NCT03055195 |

| [0,1–10] | |||||||||

| [0,1–10]Small Molecules | |||||||||

| [0,1–10]Inhibition of the JAK-STAT signaling pathway | |||||||||

| Baricitinib | JAK1, JAK2 | PO | Moderate to severe | IIIII | CompletedActive | Randomization 1:1:1 (baricitinib 2?mg, 4?mg, placebo) once dailyAlong with topical application of corticosteroids | EASI-50: higher proportion of patients for baricitinib 4?mg/d vs. placebo (61% vs. 37%; P?=?.027) at 16 weeks | Good tolerability (no cases of neoplasm or thrombotic or cardiovascular events), no cases of herpes zoster | NCT02576938NCT03334396NCT03334422NCT03334435NCT03428100NCT03435081NCT03559270NCT03733301NCT03952559 |

| Upadacitinib (ABT-494) | JAK1 | PO | Moderate to severe | IIbIII | CompletedActive | Randomization 1:1:1:1 (upadacitinib 7.5, 15 and 30?mg vs. placebo) | Mean reduction in EASI at 16 weeks for doses of 30/15/7.5?mg was 74%/62%/39% vs. placebo (23%); P? | Good tolerability. Upper respiratory tract infection and acne. | NCT02925117NCT03607422NCT03568318NCT03738397NCT03661138 |

| Abrocitinib (PF-04965842) | JAK1 | PO | Moderate to severe | IIbIII | CompletedActive | Randomization 1:1:1:1:1 (abrocitinib 10, 30, 100, and 200?mg, placebo) once daily | Percentage IGA 0-1 and improvement of ?=?2 points compared with baseline, significantly greater for abrocitinib 200?mg/d vs. placebo (44.5% vs. 6.3%) at 12 weeks | Good tolerability, on case of eczema herpeticum and one of pneumonia | NCT02780167NCT03349060NCT03422822NCT03575871NCT03627767NCT03720470 |

| ASN002 | PAN-JAK (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, TYK), SYK | PO | Moderate to severe | III | Completed | Randomization 1:1:1:1 (ASN002 20, 40 and 80?mg vs. placebo)For 28 days | Proportion of patients who achieved EASI-75 significantly greater for ASN002 40?mg (71.4%; P?=?.06) and for ASN002 80?mg (33.3%; P?=?.65) vs. placebo (22.2%) | Good tolerability | NCT03139981NCT03531957 |

| [0,1–10] | |||||||||

| [0,1–10]PDE4 antagonism | |||||||||

| Apremilast | PDE4 | PO | Moderate to severe | II | Completed | Parallel design 1:1:1:1 (apremilast 30?mg/12?h, 40?mg/12?h vs. placebo/apremilast 30?mg/12?h vs. placebo/apremilast 40?mg/12?h) | Significant reduction in EASI compared with baseline at 12 weeks with apremilast 40?mg/12?h vs. placebo (31.57% vs. 10.98%; P?=?.034). No benefit in terms of EASI/50 or pruritus. No significant differences at 30?mg/12?h | Diarrhea, nausea, abdominal discomfort | NCT02087943 |

| [0,1–10] | |||||||||

| H4R antagonism | |||||||||

| JNJ-39758979 | H4R | PO | Moderate | II | Discontinued (adverse effects) | JNJ-39758979 300 or 100?mg vs. placebo once daily | Early termination of the clinical trial | Two cases of neutropenia | NCT01497119 |

| ZPL389 | H4R | PO | Moderate to severe | II | Completed | ZPL-389 30?mg vs. placebo once daily | Significant improvement in EASI (50% vs. 27%). No significant differences in terms of pruritus | Good tolerability | NCT02424253NCT03517566 |

| [0,1–10] | |||||||||

| [0,1–10]NKR1 blockade | |||||||||

| Serlopitant | NKR1 | PO | Mild, moderate, or severe | II | Completed | Randomization 1:1:1 (serlopitant 1 and 5?mg vs. placebo)6 weeks | Nonsignificant reduction in pruritus compared with placebo (-2.25 vs.?-?2.32 vs.?-?2.01) | Good tolerability | NCT02975206 |

| Tradipitant | NKR1 | PO | Mild, moderate, or severe | IIIIIII | CompletedCompletedActive | Randomization 1:1 (tradipitant 100?mg/24?h vs. placebo) | Nonsignificant reduction in pruritus compared with placeboNo other results | Good tolerability | NCT02004041NCT02651714NCT03568331 |

| [0,1–10] | |||||||||

| kOR agonism | |||||||||

| Asimadolin | kOR agonist | PO | Mild, moderate, or severe | II | Completed | Randomization 1:1 (amisadolin 2.5?mg/12?h vs. placebo/12?h) | No results available | No results available | NCT02475447 |

| [0,1–10] | |||||||||

| [0,1–10]Other molecules | |||||||||

| DS107 | DGLA | PO | Moderate to severe | II | Completed | Randomization 1:1:1 (DS107 1?g vs. 2?g vs. placebo)Once daily | Results not published | Results not published | NCT02864498 |

Abbreviations, AD, atopic dermatitis; BSA Body Surface Area; CsA, ciclosporin A; DGLA, dihomo-?-linoleic acid; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index; GISS, Global Individual Signs Score; H4R, histamine 4 receptor; IGA, Investigator Global Assessment; IL, interleukin; IV, intravenous; JAK, Janus kinase; kOR, kappa opioid receptor; NKR1, neurokinin receptor 1; PDE4, phosphodiesterase 4; PO, oral route; SC, subcutaneous; SCORAD, SCORing Atopic Dermatitis; SD, single dose; Th, (lymphocyte) T helper; TSLP, thymic stromal lymphopoietin; TYK, tyrosine-kinase.

Data mentioned explicitly in the table are derived from clinical trials (ID) with text underlined.

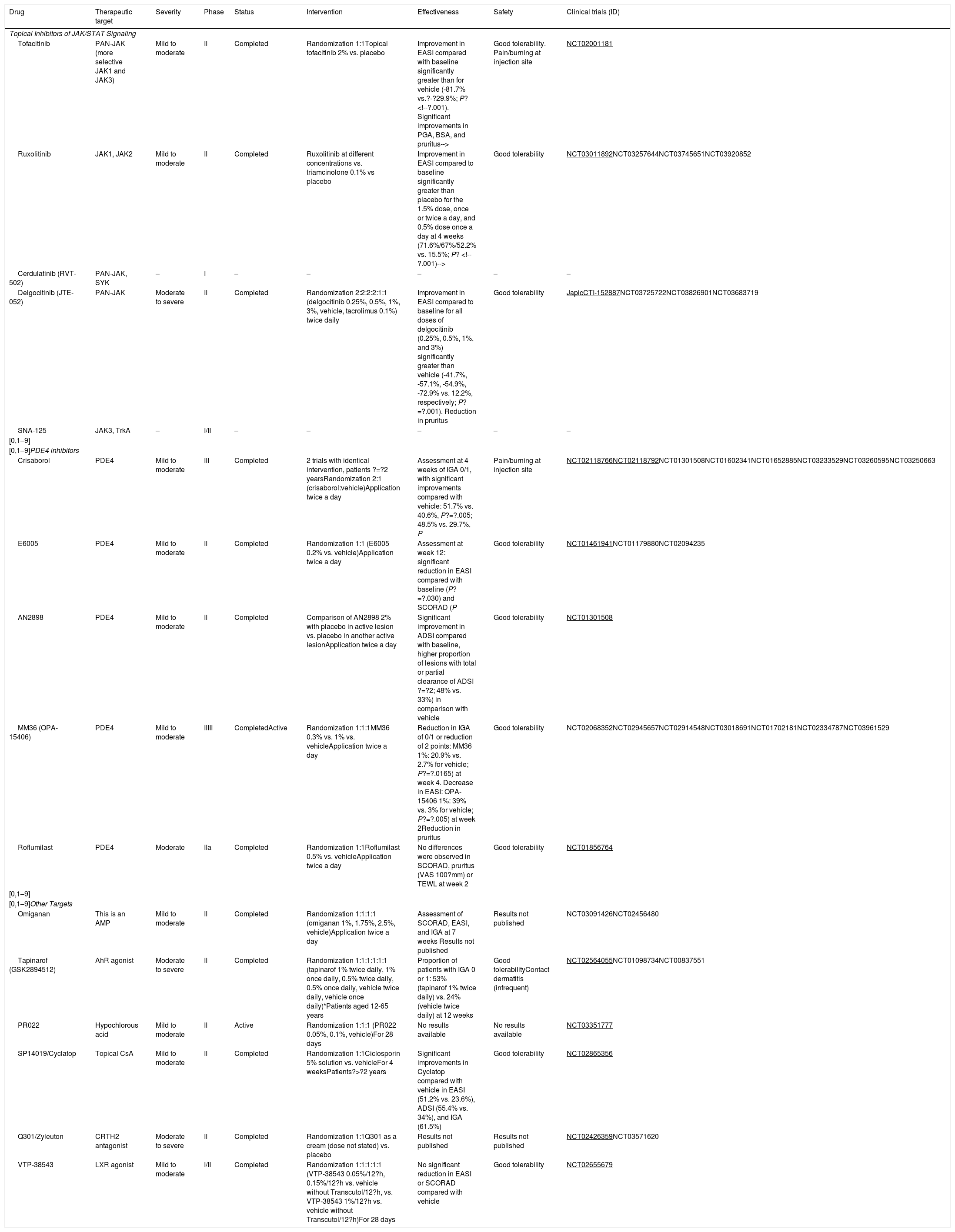

Despite progress in the development of systemic drugs, topical treatments continue to be essential both for barrier function repair and delivery of anti-inflammatory molecules. In addition to ointments, corticosteroids, and calcineurin inhibitors, new small molecules have been developed that can be used topically.

Topical Inhibitors of JAK/STAT SignalingAt present, topical inhibitors of the JAK/STAT pathway are under investigation. These include topical tofacitinib 2% and ruxolitinib 1.5%, and these agents appear to be effective at reducing EASI and pruritus.46 In a Japanese RCT, a PAN-JAK inhibitor also showed improvements in EASI that were larger than with vehicle alone, without significant adverse effects.56

PDE4 Topical InhibitorsTopical crisaborol 2% is the first PDE4 inhibitor approved in adults and children over 2 years of age with mild to moderate AD. Phase III RCTs demonstrated significantly greater efficacy measured in terms of IGA-0 (51.7%) and IGA-1 (48.5%) compared with vehicle (40.6% and 29.7%, respectively) at 4 weeks.57 Mild adverse reactions have been reported, such as application-site pain or burning. RCTs are ongoing with other PDE4 inhibitors, such as the molecules E6005 and AN2898.58

OminaganThe decreased production of antimicrobial peptides in AD facilitates microbial colonization and infection, and increases inflammatory response. Ominagan, is an antimicrobial peptide, developed in a gel formulation, that is being studied in 2 phase II RCTs; although no efficacy findings are available, good tolerability of the agent has been reported.59

TapinarofTapinarof is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent that acts as an agonist of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, an action which may improve barrier function and limit Th2 response.60 In a phase II study, the use of tapinarof 1% twice a day showed significant differences in IGA 0-1 and reduction of EASI, SCORAD, and BSA, compared with vehicle; the drug was well tolerated and there were 2 cases of contact dermatitis out of 165 patients treated.61

PR022 (Hypochlorous Acid)In a series of patients with AD, the use of topical hypochlorous acid at 0.008% and 0.002% in a hydrogel formulation was associated with a decrease in pruritus. It is thought that hypochlorous acid could lower the concentrations of different cytokines such as TNF-a, IL-2, IFN-?, and histamine.59 A phase II study is being conducted in adults with mild-moderate AD (NCT03351777).

SP14019/CyclatopSP14019/cyclatop is a topical drug formulated as a cyclosporin 5% spray under study in a phase ii RCT in patients aged more than 2 years (NCT02865356). The results, presented in the European dermatology congress in 2018, showed significant benefits in EASI and IGA compared with vehicle at 4 weeks, with good tolerability and limited systemic absorption.62

Table 2 summarizes the topical drugs under investigation.

Summary of the New Topical Treatments in Development and in Phases of Investigation for Atopic Dermatitis.

| Drug | Therapeutic target | Severity | Phase | Status | Intervention | Effectiveness | Safety | Clinical trials (ID) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topical Inhibitors of JAK/STAT Signaling | ||||||||

| Tofacitinib | PAN-JAK (more selective JAK1 and JAK3) | Mild to moderate | II | Completed | Randomization 1:1Topical tofacitinib 2% vs. placebo | Improvement in EASI compared with baseline significantly greater than for vehicle (-81.7% vs.?-?29.9%; P? | Good tolerability. Pain/burning at injection site | NCT02001181 |

| Ruxolitinib | JAK1, JAK2 | Mild to moderate | II | Completed | Ruxolitinib at different concentrations vs. triamcinolone 0.1% vs placebo | Improvement in EASI compared to baseline significantly greater than placebo for the 1.5% dose, once or twice a day, and 0.5% dose once a day at 4 weeks (71.6%/67%/52.2% vs. 15.5%; P? | Good tolerability | NCT03011892NCT03257644NCT03745651NCT03920852 |

| Cerdulatinib (RVT-502) | PAN-JAK, SYK | – | I | – | – | – | – | – |

| Delgocitinib (JTE-052) | PAN-JAK | Moderate to severe | II | Completed | Randomization 2:2:2:2:1:1 (delgocitinib 0.25%, 0.5%, 1%, 3%, vehicle, tacrolimus 0.1%) twice daily | Improvement in EASI compared to baseline for all doses of delgocitinib (0.25%, 0.5%, 1%, and 3%) significantly greater than vehicle (-41.7%, -57.1%, -54.9%, -72.9% vs. 12.2%, respectively; P?=?.001). Reduction in pruritus | Good tolerability | JapicCTI-152887NCT03725722NCT03826901NCT03683719 |

| SNA-125 | JAK3, TrkA | – | I/II | – | – | – | – | – |

| [0,1–9] | ||||||||

| [0,1–9]PDE4 inhibitors | ||||||||

| Crisaborol | PDE4 | Mild to moderate | III | Completed | 2 trials with identical intervention, patients ?=?2 yearsRandomization 2:1 (crisaborol:vehicle)Application twice a day | Assessment at 4 weeks of IGA 0/1, with significant improvements compared with vehicle: 51.7% vs. 40.6%, P?=?.005; 48.5% vs. 29.7%, P | Pain/burning at injection site | NCT02118766NCT02118792NCT01301508NCT01602341NCT01652885NCT03233529NCT03260595NCT03250663 |

| E6005 | PDE4 | Mild to moderate | II | Completed | Randomization 1:1 (E6005 0.2% vs. vehicle)Application twice a day | Assessment at week 12: significant reduction in EASI compared with baseline (P?=?.030) and SCORAD (P | Good tolerability | NCT01461941NCT01179880NCT02094235 |

| AN2898 | PDE4 | Mild to moderate | II | Completed | Comparison of AN2898 2% with placebo in active lesion vs. placebo in another active lesionApplication twice a day | Significant improvement in ADSI compared with baseline, higher proportion of lesions with total or partial clearance of ADSI ?=?2; 48% vs. 33%) in comparison with vehicle | Good tolerability | NCT01301508 |

| MM36 (OPA-15406) | PDE4 | Mild to moderate | IIIII | CompletedActive | Randomization 1:1:1MM36 0.3% vs. 1% vs. vehicleApplication twice a day | Reduction in IGA of 0/1 or reduction of 2 points: MM36 1%: 20.9% vs. 2.7% for vehicle; P?=?.0165) at week 4. Decrease in EASI: OPA-15406 1%: 39% vs. 3% for vehicle; P?=?.005) at week 2Reduction in pruritus | Good tolerability | NCT02068352NCT02945657NCT02914548NCT03018691NCT01702181NCT02334787NCT03961529 |

| Roflumilast | PDE4 | Moderate | IIa | Completed | Randomization 1:1Roflumilast 0.5% vs. vehicleApplication twice a day | No differences were observed in SCORAD, pruritus (VAS 100?mm) or TEWL at week 2 | Good tolerability | NCT01856764 |

| [0,1–9] | ||||||||

| [0,1–9]Other Targets | ||||||||

| Omiganan | This is an AMP | Mild to moderate | II | Completed | Randomization 1:1:1:1 (omiganan 1%, 1.75%, 2.5%, vehicle)Application twice a day | Assessment of SCORAD, EASI, and IGA at 7 weeks Results not published | Results not published | NCT03091426NCT02456480 |

| Tapinarof (GSK2894512) | AhR agonist | Moderate to severe | II | Completed | Randomization 1:1:1:1:1:1 (tapinarof 1% twice daily, 1% once daily, 0.5% twice daily, 0.5% once daily, vehicle twice daily, vehicle once daily)*Patients aged 12-65 years | Proportion of patients with IGA 0 or 1: 53% (tapinarof 1% twice daily) vs. 24% (vehicle twice daily) at 12 weeks | Good tolerabilityContact dermatitis (infrequent) | NCT02564055NCT01098734NCT00837551 |

| PR022 | Hypochlorous acid | Mild to moderate | II | Active | Randomization 1:1:1 (PR022 0.05%, 0.1%, vehicle)For 28 days | No results available | No results available | NCT03351777 |

| SP14019/Cyclatop | Topical CsA | Mild to moderate | II | Completed | Randomization 1:1Ciclosporin 5% solution vs. vehicleFor 4 weeksPatients?>?2 years | Significant improvements in Cyclatop compared with vehicle in EASI (51.2% vs. 23.6%), ADSI (55.4% vs. 34%), and IGA (61.5%) | Good tolerability | NCT02865356 |

| Q301/Zyleuton | CRTH2 antagonist | Moderate to severe | II | Completed | Randomization 1:1Q301 as a cream (dose not stated) vs. placebo | Results not published | Results not published | NCT02426359NCT03571620 |

| VTP-38543 | LXR agonist | Mild to moderate | I/II | Completed | Randomization 1:1:1:1:1 (VTP-38543 0.05%/12?h, 0.15%/12?h vs. vehicle without Transcutol/12?h, vs. VTP-38543 1%/12?h vs. vehicle without Transcutol/12?h)For 28 days | No significant reduction in EASI or SCORAD compared with vehicle | Good tolerability | NCT02655679 |

Abbreviations, ADSI Atopic Dermatitis Severity Index; AhR, aryl hydrocarbon receptor; AMP, antimicrobial peptide; BSA, Body Surface Area; CRTH2, prostaglandin 2 transmembrane receptor; CsA, ciclosporin A; EASI, Eczema Area and Severity Index; IGA, Investigator Global Assessment; LXR, liver X receptors; JAK, Janus kinase; PDE4, phosphodiesterase 4; PGA, physician global assessment; SCORAD, SCORing Atopic Dermatitis; SYK, spleen tyrosine kinase; TEWL, transepidermal water loss; TrkA, tyrosine receptor kinase-A; VAS, visual analog scale.

Data mentioned explicitly in the table are derived from clinical trials (ID) with text underlined.

In recent years, a better understanding of the pathogenesis of AD extending beyond the Th2 axis has led to the development of new biologics and small molecules, administered both topically and systemically, that target key elements of inflammation. Although psoriasis is a reference for translational medicine given its similarities with AD, the results for AD are still some way off those achieved with psoriasis. Currently, there is still discussion as to whether the best strategy is to target specific elements of the inflammatory process via monoclonal antibodies, for example dupilumab, or use broader-action molecules with a less specific mechanism of action such as upadacitinib. Progress in the study of new therapies and stratification of AD into different subtypes and subphenotypes in the coming years is essential to develop effective, long-term treatments with an acceptable safety profile, especially in the moderate to severe forms.

Conflicts of interestJ.M. Carrascosa has received speaker and consultant fees from Sanofi and as an investigator in clinical trials for Sanofi, Lilly, Leo-Pharma, Pfizer, and Amgen. M. Munera-Campos has participated as an investigator and received fees for clinical trials sponsored by Lilly, Leo-Pharma, and Pfizer.

Please cite this article as: Munera-Campos M, Carrascosa JM. Innovación en dermatitis atópica: de la patogenia a la terapéutica. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;111:205–221.