Mycobacterium chelonae is an atypical or nontuberculous mycobacteria belonging to the Runyon group of nonpigmented, rapidly growing mycobacteria. Infection with M chelonae takes the form of either infection of the soft tissue and bones as a result of direct inoculation (the clinical spectrum varies from localized skin abscesses to frank osteomyelitis) or a disseminated infection, usually found in the context of immunodepression. Fever, night sweats, and weight loss are the most common symptoms, and the skin lesions present as diffuse subcutaneous nodules and abscesses.1

Adalimumab is a fully human anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α monoclonal antibody. TNF-α plays a very important role in the regulation of immune responses against intracellular pathogens. Consequently, many of the adverse effects that could potentially lead to high morbidity and mortality in patients on anti-TNF therapy are due to lowered resistance to infection. TNF increases the phagocytic capacity of macrophages while promoting the destruction of intracellular pathogens, granuloma formation, and the sequestration of mycobacteria, thereby preventing their spread.2

We report the case of a 76-year woman with history of type 1 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and seropositive rheumatoid arthritis diagnosed 20 years earlier. She had been treated with corticosteroids and methotrexate from 1992 to 2000, corticosteroids and azathioprine from 2000 to 2003, and corticosteroids and adalimumab from 2003 to 2009. Treatment with adalimumab had been suspended from October to December 2008 due to cytomegalovirus infection and reintroduced in January 2009.

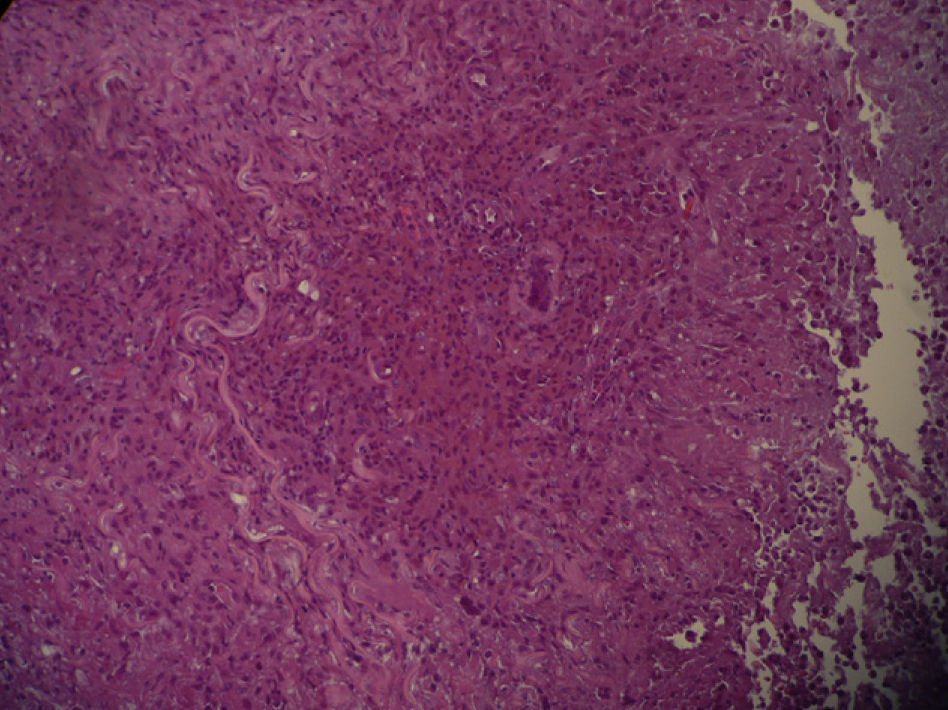

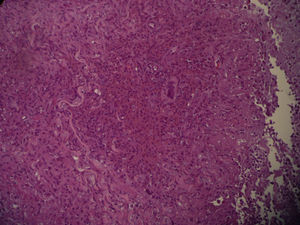

In September 2009, she was admitted to the internal medicine department in our hospital for the assessment of an episode of hypoglycemia. When her medical history was being taken, the patient reported inflammation of the right foot, which had started a month earlier, a fistula orifice on the heel, and febrile episodes 3 to 4 times a week in the preceding months. Physical examination on admission revealed firm erythematous-violaceous plaques and nodules localized mainly on the limbs (Fig. 1), and dermatologic evaluation was therefore requested.

The most notable findings from the workup carried out were an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 100, a rheumatoid factor of 53.5, and evidence of osteomyelitis of the first metatarsal and the calcaneus of the right foot on the scintigraphic bone scan. The other results of the blood count, biochemistry, coagulation studies, serology, and a thoracoabdominal computed tomography (CT) were normal.

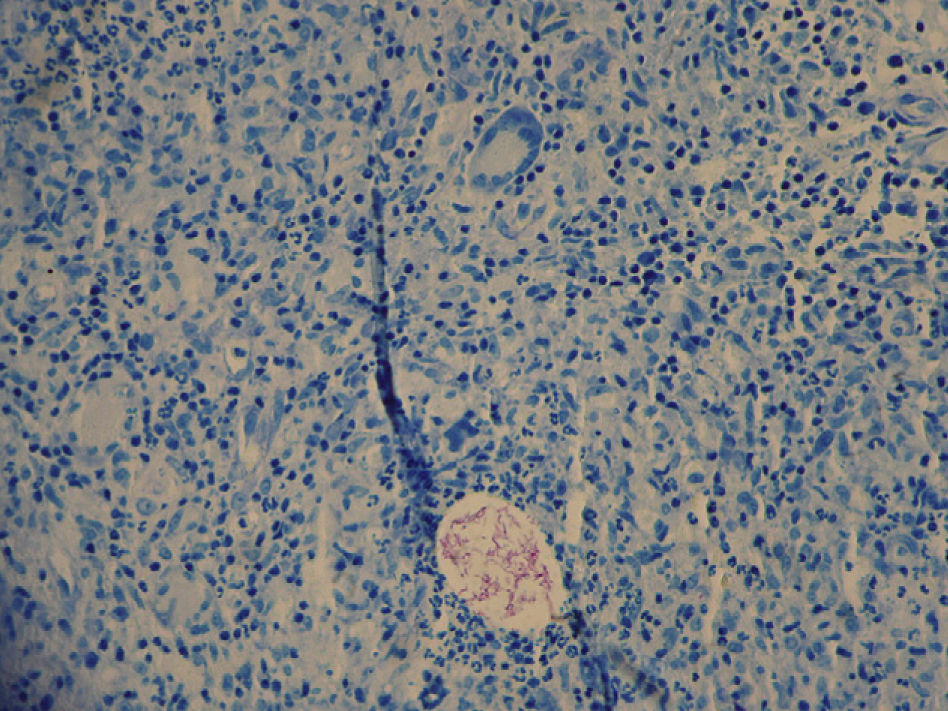

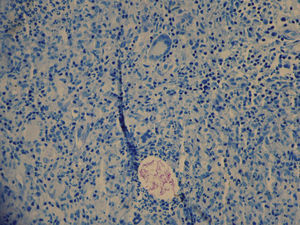

Two skin biopsies were obtained, one for dermatopathology and one for microbiological analysis. Histology revealed an inflammatory mycobacterial granuloma (Fig. 2), and Ziehl staining showed Ziehl-positive bacilli distributed in groups between the inflammatory cells (Fig. 3). The other sample was smear microscopy-positive for mycobacterium and culture-positive for M chelonae.

On the basis of these results, a diagnosis of disseminated M chelonae infection was established. Treatment with intravenous imipenem 0.5g/6h and oral clarithromycin 500mg/day was initiated and continued for the month the patient remained in the hospital. After discharge, treatment was continued with a regimen of oral levofloxacin 500mg/24hours and clarithromycin 500mg/24hours for a further 6 months. Fifteen days after the start of antibiotic treatment, lavage and curettage of the lesion on the right foot was performed. The bone was observed to have a granulomatous appearance, and microscopically there was evidence of chronic granulomatous osteomyelitis though staining for acid-alcohol-fast bacilli, smear microscopy, and culture were all negative.

Although the most common mycobacterial infections in patients on anti-TNF therapy are caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, atypical mycobacterial infections are increasingly being reported. This trend may be due to the fact that such patients are actively screened for M tuberculosis because of the reports of infection in the literature. Also relevant is the fact that the vast majority of the cases of tuberculosis reported have occurred within 3 months of starting anti-TNF therapy, a finding that suggests reactivation of latent infection, something that has not been demonstrated in the case of other mycobacterial infections.

Winthrop et al. reviewed the U.S. Food and Drug Administration MedWatch database for cases of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections in patients receiving anti-TNF therapy.3 They reported that the population affected had a mean age of 62 years and was predominantly female (66.65%). The underlying pathology was rheumatoid arthritis in the majority of these patients (73.70%).

Since 2002, several cases of nontuberculous or atypical mycobacterial infection have been reported in patients receiving anti-TNF therapy.4–7

On reviewing the literature, we found the following 3 cases relating specifically to M chelonae: 1 reported in 2006 by Sicot et al8 in a patient treated with infliximab; another in 2008 in which Diaz et al9 described a patient treated with adalimumab for rheumatoid arthritis whose lesions developed 2 months after the start of biologic treatment; and the third reported by Adenis-Lamarre et al10 in 2009 in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis receiving adalimumab who developed skin lesions and was subsequently diagnosed with M chelonae infection.

Our case differs from those described above in the duration of treatment of the patient with adalimumab (6 years) because in the other cases reported, the infection developed within a few months of the start of treatment. We are also of the opinion that our patient's osteomyelitis may also have been caused by the M chelonae infection, although this hypothesis could not be confirmed by histology or microbiology because the patient had already been receiving appropriate antibiotic therapy for 15 days when samples were obtained.

In conclusion, anti-TNF therapy has been associated with opportunistic infections and patients receiving such therapy should be considered to be immunosuppressed. The risk level for infection due to nontuberculous mycobacteria in these patients is not yet known. However, the frequent presence of additional risk factors, such as concomitant treatment with other immunosuppressants (corticosteroids, methotrexate) and the underlying disease itself, make it difficult to estimate the specific weight of these new drugs in the process.

Please cite this article as: Conejero R, Ara M, Lorda M, Rivera I. Infección por Mycobacterium chelonae en paciente en tratamiento con adalimumab. Actas Dermosifliogr. 2012;103:70-71.