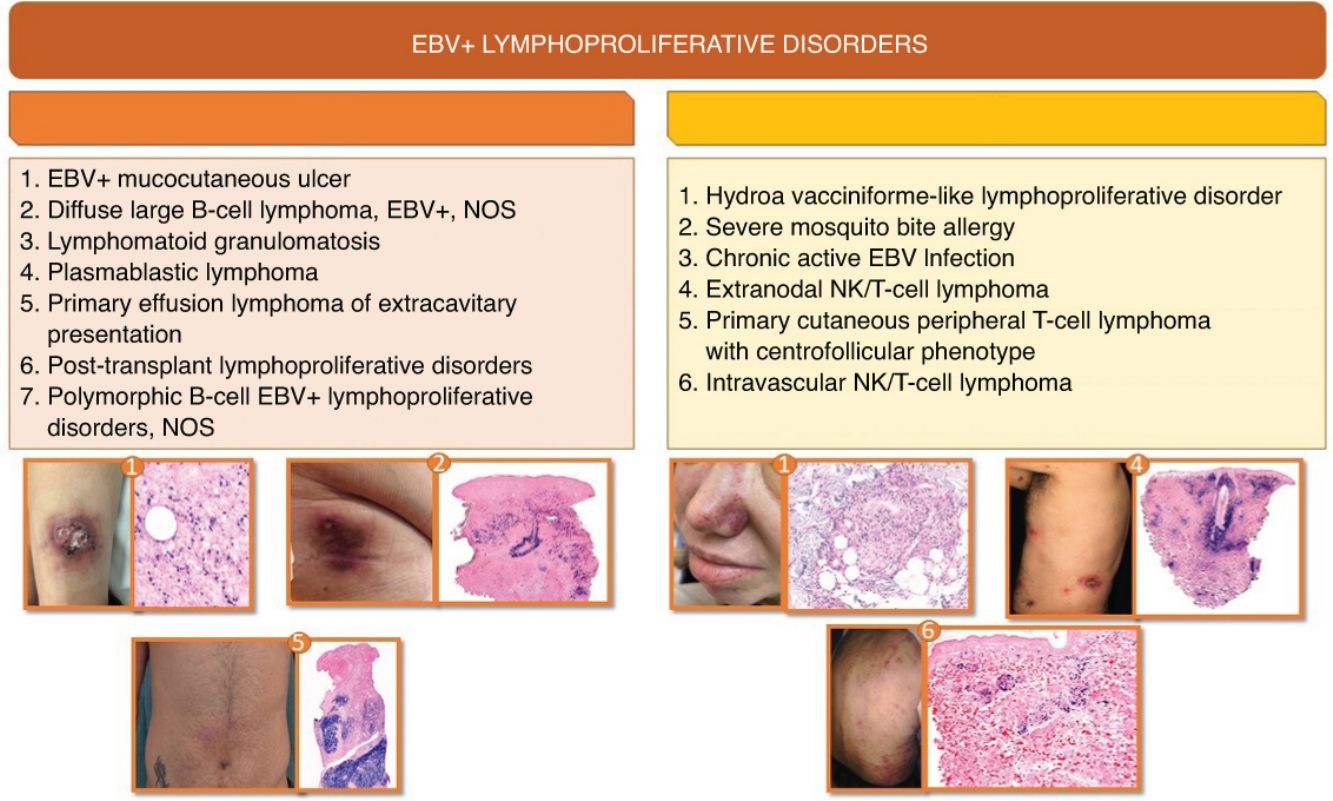

Epstein Barr virus (EBV) positive B lymphoproliferative disorders (LPD) with cutaneous involvement include a series of rare entities that go from indolent processes to aggressive lymphomas. B-cell EBV+ LPD mainly affect immunocompromised patients while T-cell EBV+ LPD are more prevalent in specific geographic regions such as Asia, Central America, and South America. Since the latest WHO-EORTC classification of cutaneous lymphomas in 2018, significant changes have been included in the new classifications of hematological malignancies. This systematic review summarizes the main clinical, histological, immunophenotypic and molecular characteristics of B- and T-cell EBV+ LPD that may compromise the skin at diagnosis. B-cell EBV+ LPD include primary cutaneous lymphomas such as EBV-Mucocutaneous Ulcer, as well as systemic lymphomas affecting the skin at diagnosis that may present such as lymphomatoid granulomatosis (LG), EBV diffuse large B cell lymphoma, NOS, plasmablastic lymphoma (PBL), extracavitary primary effusion lymphoma (EC-PEL) EBV+, EBV-positive polymorphic B cell LPD, and post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD). Regarding T-cell EBV+ LPD, most of these entities are categorized within T/NK-cell lymphoproliferative processes and lymphomas of childhood, including extranodal T/NK lymphoma, and even more exceptional forms such as EBV-positive T-cell centrofollicular lymphoma and intravascular T/NK-cell lymphoma. Diagnosis is based on integrating the clinical, histological, immunohistochemical, and genetic criteria discussed throughout this article. Differential diagnosis is a challenge for dermatologists and pathologists, so having scientific evidence available in this field is of paramount importance because overtreatment must be carefully avoided.

Los procesos linfoproliferativos (PLP) positivos para el virus de Epstein-Barr (VEB) con afectación cutánea son una serie de entidades poco frecuentes que engloban desde procesos indolentes a linfomas agresivos. Los procesos linfoproliferativos B (PLP B) afectan principalmente a los pacientes inmunocomprometidos y los procesos linfoproliferativos T (PLP T) son más frecuentes en determinadas regiones geográficas como Asia, América Central y Sudamérica. Desde la última clasificación de la clasificación de consenso común de la Organización Mundial de la Salud y de la Organización Europea para la Investigación y el Tratamiento del Cáncer (WHO/EORTC) de los linfomas cutáneos en 2018 se han producido cambios significativos para estas entidades en las nuevas clasificaciones de las neoplasias hematológicas. En esta revisión sistemática se incluyen las principales características clínicas, histológicas, inmunofenotípicas y moleculares de los PLP B y T VEB+ que pueden afectar a la piel al diagnóstico. Entre los PLP B se incluyen linfomas primarios cutáneos como la úlcera mucocutánea positiva para el virus de Epstein-Barr (UMC VEB+) y linfomas sistémicos que pueden presentarse con afectación cutánea como la granulomatosis linfomatoide (GL), el linfoma difuso de células grandes B asociado al virus de Epstein-Barr, No especificado (LCGBD VEB+, NOS) el linfoma plasmablástico (LPB), el linfoma primario de cavidades con presentación extracavitaria (EC-PEL) VEB+, el proceso linfoproliferativo polimorfo B VEB+ o los PLP postrasplante (PLPPT). Dentro de los PLP T, la mayoría están englobados dentro de los PLP y linfomas de células T/NK de la infancia, así como el linfoma T/NK extranodal y formas aún más excepcionales como el linfoma T de célula centrofolicular VEB+ y el linfoma intravascular de célula T/NK. El diagnóstico diferencial de estas entidades es un reto para clínicos y patólogos, por lo que disponer de evidencia científica de calidad en este campo es de gran importancia para evitar el sobretratamiento.

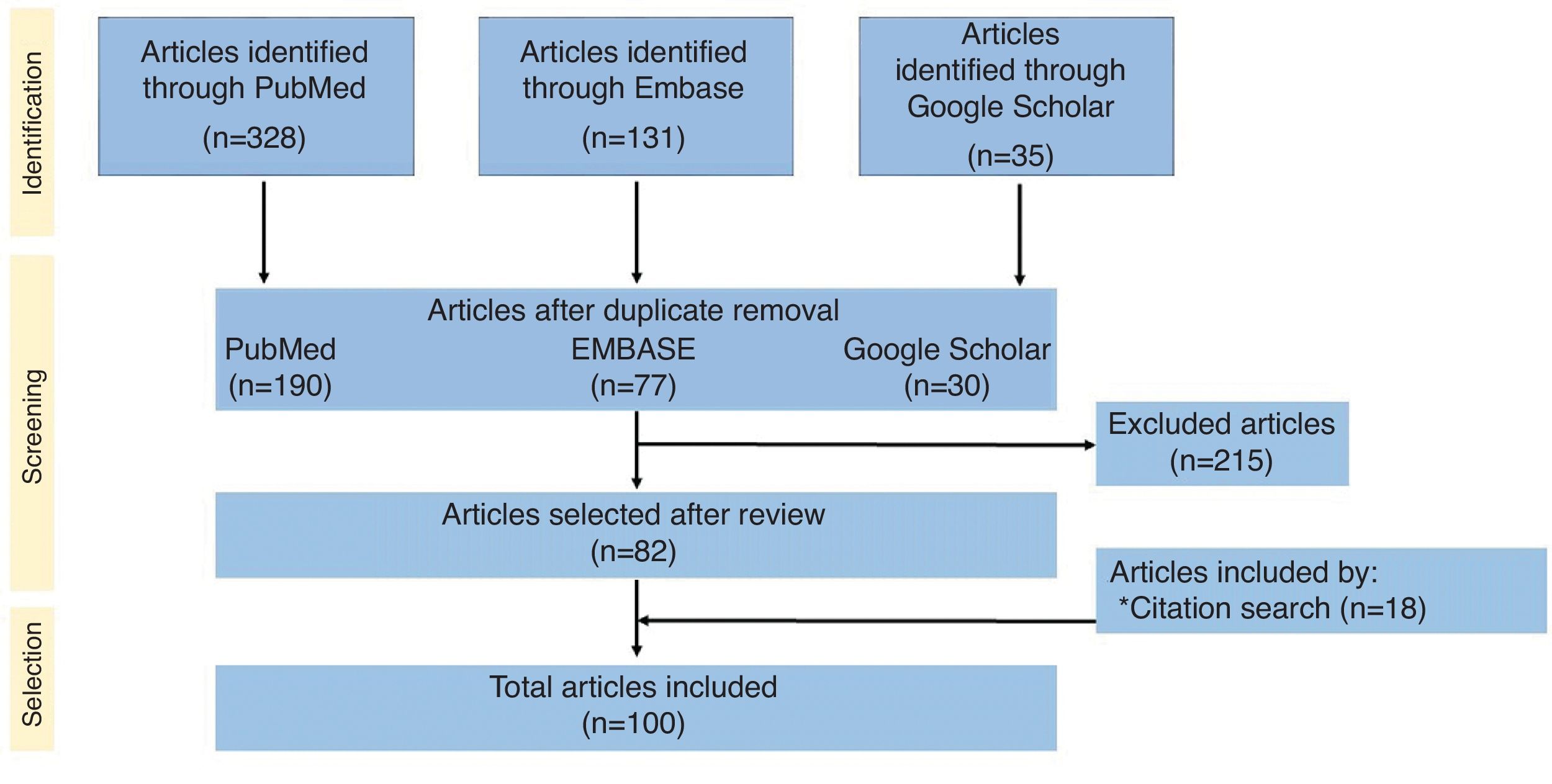

The classification of lymphomas has evolved significantly in recent years. Since the 2018 consensus classification by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC),1 not one but two new classifications/expert consensus documents on hematolymphoid neoplasms2,3 have recently been published, along with the newly released WHO classification of cutaneous neoplasms.4 Advances in diagnostic techniques, and new discoveries on the pathogenesis and genetics of these entities, have brought substantial changes to their classification and the definition of some of them. This systematic review focuses on Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-related lymphoproliferative disorders (LPDs) and B- and T-cell lymphomas that can present with cutaneous involvement, also addressing the role of EBV in lymphomagenesis. The methodology of the review can be found in Annex B,5,10 as well as in Fig. 1, which provides a summary of the systematic review methodology. Additionally, Annex B includes the main clinicopathological characteristics of the entities discussed in this article. Finally, Annex B summarizes nomenclature equivalences for these processes across various current and predecessor classifications. For readability purposes, the text refers to entities by their names in the international consensus classification (ICC).

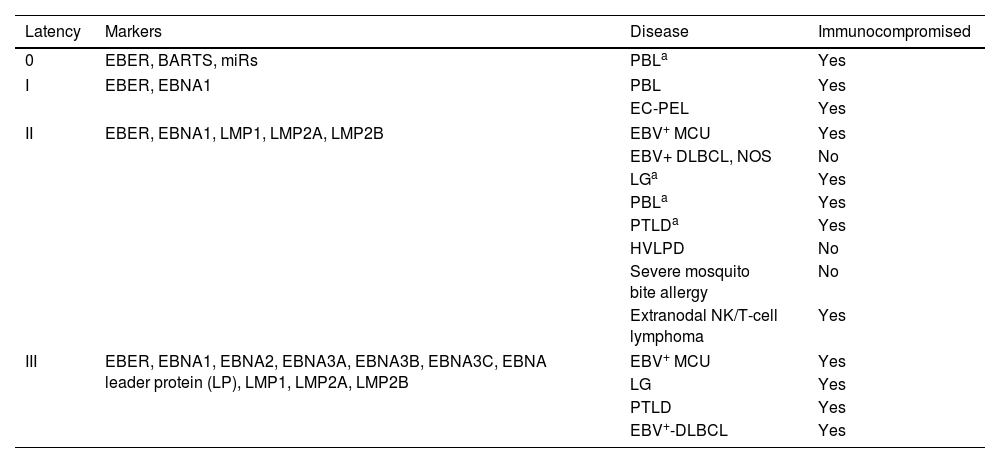

ResultsThe role of Epstein–Barr virus in lymphomagenesisOver the past few decades, efforts have been made to clarify the role of certain viral infections in the emergence of cutaneous lymphomas.7 Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) was the first human virus associated with tumors, discovered in 1964 in Burkitt's lymphoma.8 The EBV is a gamma herpesvirus, widely prevalent, infecting over 90% of the global population.9 Following primary infection, EBV persists for life in memory B cells.10 Most infected individuals control the infection through cytotoxic immune responses by NK cells or CD8+ T lymphocytes. Only a small subset develops chronic EBV infection and associated diseases, more commonly in the presence of immunodeficiency, genetic predisposition, or environmental factors.10 EBV exhibits various types of latent infection, largely determined by the host's immune status. These are characterized by the limited expression of viral genes, which vary across EBV-associated tumors (Table 1).

EBV latencies and their relationship with EBV+ B and T lymphoproliferative disorders and immune status.

| Latency | Markers | Disease | Immunocompromised |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | EBER, BARTS, miRs | PBLa | Yes |

| I | EBER, EBNA1 | PBL | Yes |

| EC-PEL | Yes | ||

| II | EBER, EBNA1, LMP1, LMP2A, LMP2B | EBV+ MCU | Yes |

| EBV+ DLBCL, NOS | No | ||

| LGa | Yes | ||

| PBLa | Yes | ||

| PTLDa | Yes | ||

| HVLPD | No | ||

| Severe mosquito bite allergy | No | ||

| Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma | Yes | ||

| III | EBER, EBNA1, EBNA2, EBNA3A, EBNA3B, EBNA3C, EBNA leader protein (LP), LMP1, LMP2A, LMP2B | EBV+ MCU | Yes |

| LG | Yes | ||

| PTLD | Yes | ||

| EBV+-DLBCL | Yes | ||

In EBV latency states, up to 6 EBV nuclear antigens (EBNA1, 2, 3A, 3B, 3C, and LP), 3 latent membrane proteins (LMP1, 2A, and 2B), and 2 EBV-encoded RNAs (EBER1 and 2) can be expressed. This table shows the relationship of these markers with latency states, associated lymphoproliferative disease, and the presence or absence of immunocompromised status.

Lymphoproliferative processes that may present other types of latencies and/or markers less commonly.

EBER: EBV-encoded small RNA; EBNA: EBV nuclear antigen; BARTS: BamHI fragment A rightward transcript; LMP: latent membrane protein; miRs: microRNAs; EBV+ MCU: EBV+ mucocutaneous ulcer; EBV+-DLBCL, NOS: EBV+ diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified; LG: lymphomatoid granulomatosis; PBL: plasmablastic lymphoma; EC-PEL: extracavitary primary effusion lymphoma; PTLD: post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder; HVLPD: hydroa vacciniforme-like lymphoproliferative disorder.

The precise mechanisms through which latent EBV infection initiates lymphoid cell transformation and neoplastic progression remain unclear, though several predisposing factors exist. For each tumor entity and location, differences are observed in gene expression profiles, tumor metabolism, signal transduction, immune evasion mechanisms, and the composition of the tumor microenvironment depending on EBV association.11

Notably, EBV+ lymphomas may develop multiple immune evasion mechanisms, making them potential candidates for immunotherapy. Treatment approaches include programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) antibodies, small molecules targeting EBV latency gene products, cellular vaccines, and even chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell therapies targeting EBV antigens.11,12

EBV-related lymphoproliferative disorders and B-cell lymphomas with cutaneous involvementThese entities comprise a clinicopathological spectrum ranging from indolent, self-limited processes to highly aggressive ones. Immunosuppression often plays a critical role in their pathogenesis.

EBV+ mucocutaneous ulcerFirst described in 2010 in a series of 26 patients,13 it is the only entity classified as a primary cutaneous LPD and is now recognized as a definitive entity in the latest classifications. Specifically, the 2022 ICC classification3 specifies that the condition should involve single lesions. For patients with ≥2 lesions, terms such as “EBV+ polymorphic B-cell LPD” or, when appropriate based on clinicopathological characteristics, EBV-related diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, Not Otherwise Specified (EBV+-DLBCL, NOS), are preferred.

Epidemiology and pathogenesisThis condition is more common in women,14 with a mean age of 66.4 years.15 It occurs in the context of loss of control over latent EBV infection due to various types of immunosuppression: age-related immunosenescence caused by T-cell repertoire loss and dysfunction,16 or iatrogenic immunosuppression in autoimmune diseases, solid organ transplantation, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT), or HIV infection.17 Methotrexate is the drug most frequently associated with this LPD, followed by azathioprine, cyclosporine, imatinib, tacrolimus, tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors, and mycophenolate.17 Chronic mucosal inflammation or inflammatory bowel disease are additional risk factors.18

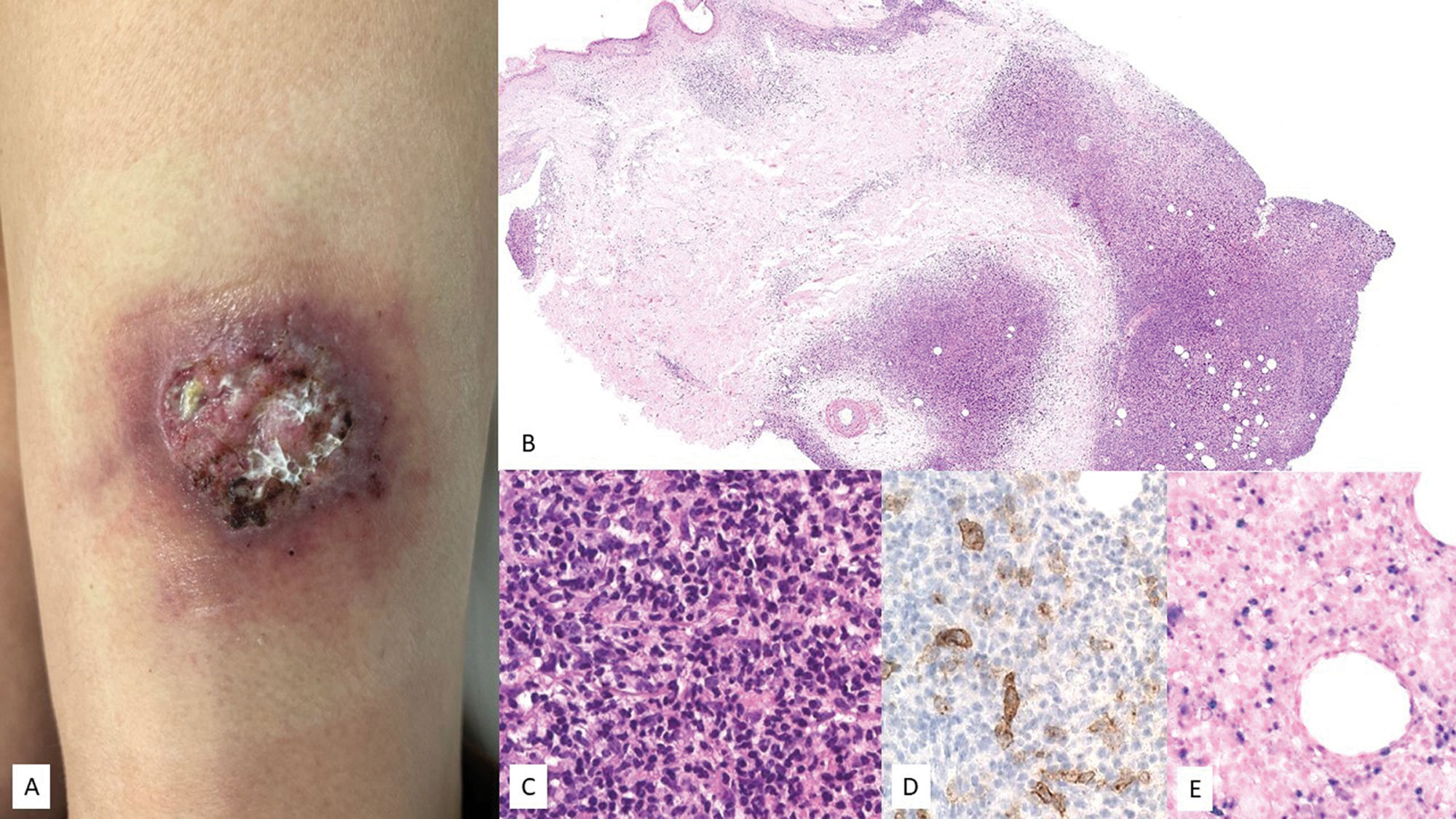

Clinical characteristicsIt presents as a solitary ulcer on the skin or mucosa (Fig. 2). Clinical course is indolent, with spontaneous resolution of lesions occasionally observed.14 Patients typically exhibit very low or undetectable EBV DNA loads in peripheral blood, aiding in the differential diagnosis from EBV+-DLBCL, NOS.19 Rare cases with intermittent-recurrent courses without progression have been described.20

EBV+ mucocutaneous ulcer (EBV+-MCU). (A) Clinical image showing an isolated ulcer with necrotic areas and surrounding erythema located on the anterior aspect of the left thigh. (B) At low magnification, a dermal infiltrate with intense involvement of the deep portion and a nodular pattern is observed (H&E, 2×). (C) At higher magnification, the infiltrate is heterogeneous, with atypical elements of Sternberg-like habit (H&E, 20x). (D) Part of the infiltrate tests positive for CD30 (20×); and (E) positive for EBER (20×).

Biopsies show superficial ulcers with epidermal or mucosal acanthosis, sometimes with pseudoepitheliomatous changes.13 The inflammatory and tumoral infiltrate at the ulcer base is heterogeneous, with plasmacytoid Hodgkin-like apoptotic cells and necrosis, highly characteristic of these lesions14 (Fig. 2). Furthermore, CD3+ T-cell rings are typically found at the base. Hodgkin-like immunoblasts show variable PAX5+ intensity, and positivity for OCT2+, MUM1+, BOB1+, and CD45+/−. CD20 expression is partial or absent in up to 33% of cases.13 These cells are typically CD30+ (Fig. 2), often co-expressing CD15 in a significant subset.19 EBER positivity is seen in Hodgkin-like cells, smaller lymphocytes, and occasionally adjacent epithelial cells.6,14 PDL1 expression has been reported in tumor cells in some series.6 B-cell clonality is detected in <50% of patients, while T-cell clonality or oligoclonality is common due to immunosenescence and other immune defects.14

Updates on treatmentMany cases resolve spontaneously or after discontinuing immunosuppression. In elderly patients without other immunosuppressive factors, good responses to IV rituximab monotherapy have been described.14 Other published treatments include polychemotherapy regimens, such as the combination of rituximab with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine sulfate, and prednisone (R-CHOP), or radiotherapy.18

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma associated with Epstein–Barr virus, not otherwise specifiedThis entity was first described in 2003 in a series of non-immunosuppressed patients over 60 years old, characteristically presenting with predominant extranodal involvement.21 These patients appeared to have a worse prognosis compared with EBV negative-DLBCL cases (EBV−). In the 2008 WHO classification, it was included as a provisional entity under the name “EBV+-DLBCL of the elderly”.22 Over time, cases in younger patients were reported, leading to the name change to “EBV+-DLBCL, NOS” in the 2016 WHO classification.

Epidemiology and pathogenesisIts prevalence is higher in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. It has been described across a wide age range but is more common in individuals older than 50 years and often presents with extranodal involvement (40% of cases). Unlike older patients, younger patients (<45 years) more frequently exhibit nodal disease and tend to have a better prognosis.14

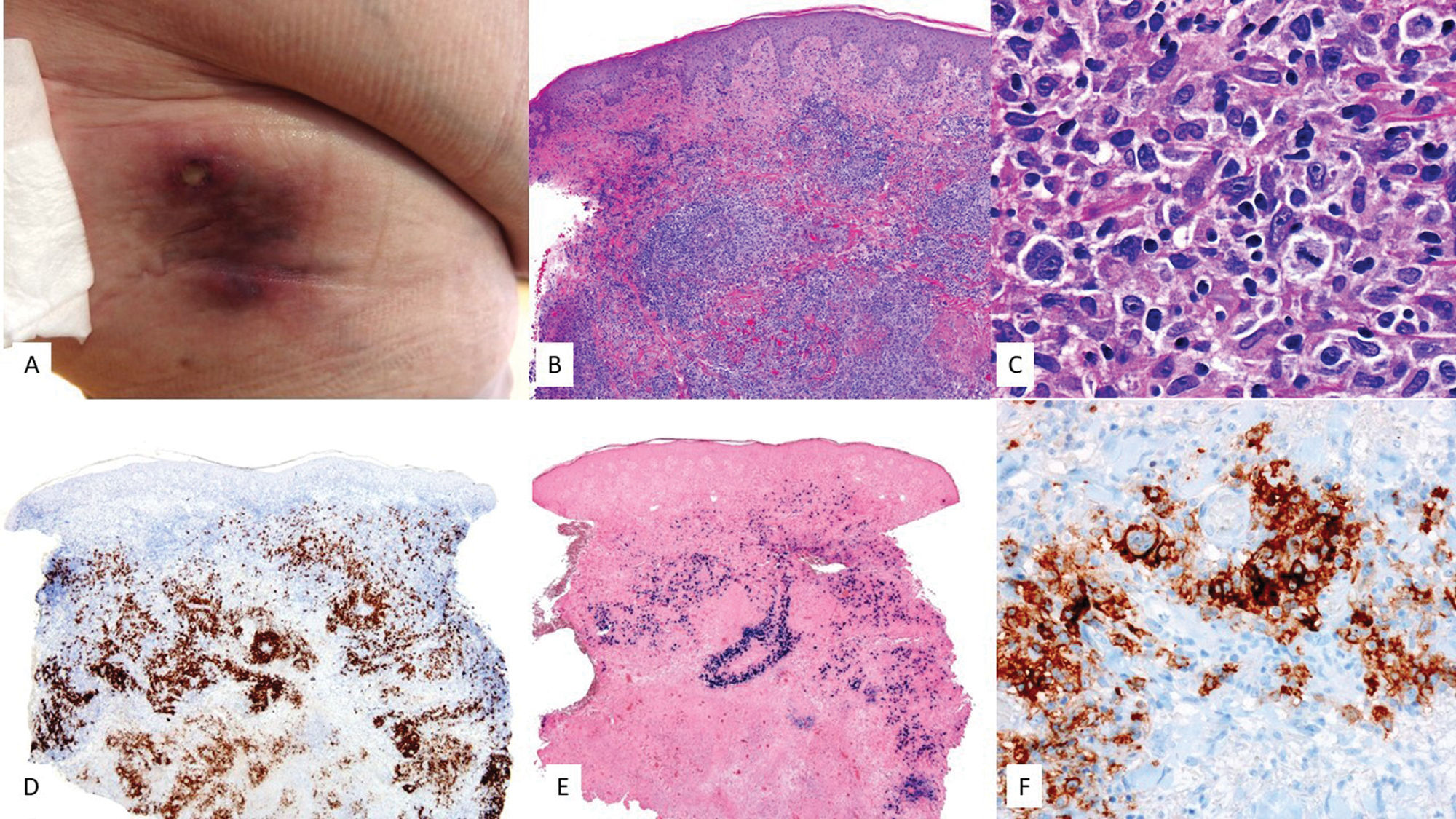

Clinical featuresCutaneous lesions typically consist of plaques, nodules, or tumors, generally non-ulcerated, located on the lower extremities19 (Fig. 3). Overall, advanced disease is common at diagnosis, with high EBV viral loads in peripheral blood (PB).23 A recent systematic review drew a comparison between 17 cases of this lymphoma with cutaneous presentation and 21 cases of primary cutaneous DLBCL, leg type (LT). It highlighted clinicopathological differences between the 3 entities, as well as a worse prognosis for EBV+ DLBCL, NOS (median overall survival, 32 months vs 88 months for LT).29 Patients with EBV+ DLBCL, NOS are significantly older at diagnosis, more likely to have non-nodular lesions, and exhibit multiple skin lesions and locations.29

EBV-related diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, unspecified. (A) Clinical image showing an indurated erythematous–violaceous plaque infiltrating the upper region of the right thigh in an elderly patient. (B) At low magnification, a dermal infiltrate in the superficial and deep portions with a nodular pattern is observed (H&E, 2×). (C) At higher magnification, the infiltrate looks heterogeneous with the presence of large cells of atypical morphology and Sternberg-like habit (H&E, 20×). These cells are (D) positive for CD30 (2×), (E) EBER (2×), and (F) CD20 (2×).

A spectrum of morphological presentations exists, ranging from monomorphic cases with sheets of atypical large lymphocytes and no reactive inflammatory cells, to polymorphic cases with reactive inflammatory infiltrates and scattered atypical large lymphocytes (Fig. 3). In skin, monomorphic infiltrates are the most common ones.24 The prognostic significance of histology is debated. In adults, it does not appear to have prognostic implications,14 whereas in younger patients (<45 years), the polymorphic pattern suggests a better prognosis.14 Additionally, approximately 22.7% of cutaneous cases show an angiocentric pattern. Phenotypically, most atypical lymphocytes are positive for CD20, CD79a, MUM1, and CD30, with variable expression of BCL2 and BCL6.24 CD30 (Fig. 3) and EBER positivity (Fig. 2F) are key immunophenotypic differences from LT.24 PD-L1 and PD-L2 are frequently expressed in younger vs older patients, suggesting an immune evasion mechanism.25

Unlike EBV-negative DLBCL, EBV+-DLBCL, NOS26 often features mutations in the nuclear factor kappa beta (NF-κB) pathway, Wingless (WNT) signaling pathway, and interleukin 6/Janus kinase-signal transducers and activators of transcription (IL6/JAK/STAT) pathway.27 Similarly, integrated whole-genome sequencing and targeted amplicon sequencing clearly differentiate this tumor type from EBV−DLBCL due to frequent mutations in ARID1A (45%), KMT2A/KMT2D (32/30%), ANKRD11 (32%), and NOTCH2 (32%).27

Treatment updatesThese cases respond poorly to typical chemotherapy regimens like R-CHOP. Some clinical trials with anti-CD30 antibodies, such as brentuximab combined with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (BV-R-CHP), or anti-CD79b antibodies like polatuzumab vedotin combined with R-CHP, have shown promising results. Polatuzumab R-CHP could become the treatment of choice for these patients.28,29

Lymphomatoid granulomatosisLymphomatoid granulomatosis (LG) is a rare EBV-related B-cell LPD first described in 1972. Initially considered a peripheral T-cell lymphoma due to the predominance of accompanying T-lymphocytes,30 it is now recognized as a B-cell lymphoma.31 This lymphoma typically affects the lungs, with less frequent involvement of the central nervous system (CNS), skin, kidneys, or liver.18

Epidemiology and pathogenesisIt shows a slight male predominance (2:1) and typically presents in the 4–6th decades of life, being very rare in children.18 Its pathogenesis is unclear, but several causes have been proposed, including the oncogenic potential of EBV. It has also been associated with chronic autoimmune diseases or immunodeficiencies, whether congenital or acquired, such as post-transplant LPDs (PTLPDs) or iatrogenic LPDs related to immunosuppressive drugs such as azathioprine, methotrexate, or imatinib.18,19

Clinical featuresDisease is considered extranodal, with nodal or bone marrow involvement being exceptional. Typical presentations include cough, dyspnea, and chest pain, sometimes accompanied by systemic symptoms such as fever, myalgias, malaise, or weight loss, and peripheral neuropathy. Skin lesions may appear at any stage of the disease and have been reported as the initial sign in up to one-third of patients. Clinical and morphological variability in the described lesions exists. The most common presentation is erythematous nodules—sometimes subcutaneous—on the trunk and extremities, mimicking panniculitis. Other presentations include multiple indurated plaques, lesions resembling lichen sclerosus, or even those mimicking nasal NK/T-cell lymphoma with zone ulceration and diffuse crateriform nodules.32,33 Historically associated with a poor prognosis, the introduction of novel treatments has increased the life expectancy of these patients.19,34

Histology and molecular featuresThe histology of cutaneous lesions can differ from that seen in other organs.32 In the skin, a lymphocytic or lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with a variable presence of multinucleated giant cells is typically found, presenting as panniculitis with poorly structured granulomas. These infiltrates have a characteristic angiocentric or perivascular distribution. In other cases, cutaneous lesions resemble those found in organs such as the lungs, appearing as an angiodestructive process with fibrinoid necrosis and perivascularly arranged CD20+ and EBER+ immunoblasts. EBV is harder to detect in cutaneous lesions, and biopsying non-ulcerated lesions is preferable since necrosis hinders virus detection.32 Accompanying T lymphocytes are abundant and typically express CD8 and cytotoxic markers. Large cells are positive for CD30 in up to 50% of cases, while CD15 is characteristically negative.32

A grading scheme for cases based on EBV+ cell counts exists.35 However, grading is not recommended in the skin, as different lesions may have varying numbers of EBER+ cells.

Clonal rearrangement is present in approximately 25% of cases, with variability depending on the grade (only 8% of grade 1 lesions are clonal vs 69% of grade 3 lesions).36

Treatment updatesCurrently, there are no consensus guidelines on the management of these patients. For iatrogenic cases associated with immunosuppression and low-grade lesions, reducing immunosuppression or discontinuing the immunosuppressive drug is recommended.18 Immunotherapies such as IFN-alpha or immunoglobulins have been used to promote the immune system antiviral action.37 Grade 3 lesions are treated with polyimmunochemotherapy regimens (R-CHOP) similar to those used for EBV+-DLBCL, NOS. AHSCT may also be considered.38

Plasmablastic lymphomaThis entity was first described under the name “plasmablastic lymphoma” (PBL) back in 199739 and was included in the 2001 WHO classification as an aggressive and rare variant of DLBCL.40 Primary cutaneous presentation of PBL (pcPBL) is extremely rare, with the first cases being reported between 2004 and 2005.41,42

Epidemiology and pathogenesisPBL has traditionally been considered an HIV-related disease, accounting for up to 2.6% of HIV-associated lymphomas.43,44 Currently, PBL is also recognized as being associated with other immunosuppressive states.

The prognosis for this type of lymphoma is quite poor, despite the administration of chemotherapy treatments. Notably, the presence of EBV has been associated with a better prognosis compared to cases where EBV detection tested negative.44,45 In cases of PBL with cutaneous involvement only, prognosis is more favorable.46,47

Clinical featuresThe most common presentation is extranodal, primarily in the oral cavity, followed by the GI tract. Less frequent are cases with nodal, pulmonary, nasal cavity, or cutaneous involvement.42,44,48

At skin level, PBL typically manifests on the lower extremities as one or multiple erythematous–violaceous nodules with a tendency to ulcerate.47,48 Less common cutaneous presentations include recurrent scrotal abscesses,49 enterocutaneous fistulas,50 or perineal ulcers.51 Approximately half of the cases with cutaneous symptoms already present with systemic disease at diagnosis.48

Histology and molecular featuresMost cases are characterized by a diffuse infiltrate throughout the dermis, composed of plasmablasts.42,43

Immunohistochemically, B-cell markers and CD45 are typically negative. Conversely, these cells are positive for CD138, CD38, MUM1/IRF4, and PRDM1/BLIMP1.42,43,48 EBER tests positive in more than 60% of cases,42,48 and proliferation index is usually very high (Ki67>90%). Occasionally, aberrant expression of T-cell markers can occur, complicating differential diagnosis.42,52

Treatment updatesThere is no consensus for its treatment. Various chemotherapeutic regimens are commonly used, with CHOP being one of the most frequently employed regimens.53 Other combinations have also been tested, including regimens based on etoposide phosphate, prednisone, vincristine sulfate, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin hydrochloride (EPOCH); regimens based on cyclophosphamide, vincristine sulfate, doxorubicin hydrochloride, dexamethasone, methotrexate, and cytarabine (HyperCVAD); or regimens alternating high-dose cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and methotrexate with ifosfamide, etoposide, and cytarabine (CODOX-M/IVAC),43,53 with variable response. Currently, clinical trials are being conducted with bortezomib, ganciclovir, and CAR-T therapies.43

In the case of primary pcPBL, surgical excision along with adjuvant radiotherapy can be considered as a more conservative treatment, or chemotherapy in the presence of multiple lesions.45

Primary cavity lymphoma of extracavitary presentation, EBV+This entity was first recognized in the WHO classification of 200154,55 as a rare and aggressive type of non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma defined by the presence of human herpesvirus type 8 (HHV8). Coinfection with EBV is relatively common.55

Epidemiology and pathogenesisThis lymphoma occurs more frequently in people with HIV but can also arise in other states of immunocompromise, such as elderly immunosenescent patients or solid organ transplant recipients.2,56 HIV+ or elderly patients are typically HHV8+ and EBV+.56

Clinical featuresClassically, this lymphoma affects body cavity effusions such as pleura, peritoneum, and pericardium. However, there is a solid extracavitary (EC) variant involving nodal and extranodal sites, mainly the GI tract and skin.56 In the skin, with fewer than 15 published cases, it shows as subcutaneous nodules,57 panniculitis-like lesions,58 or Kaposi sarcoma-like lesions (Fig. 4).59

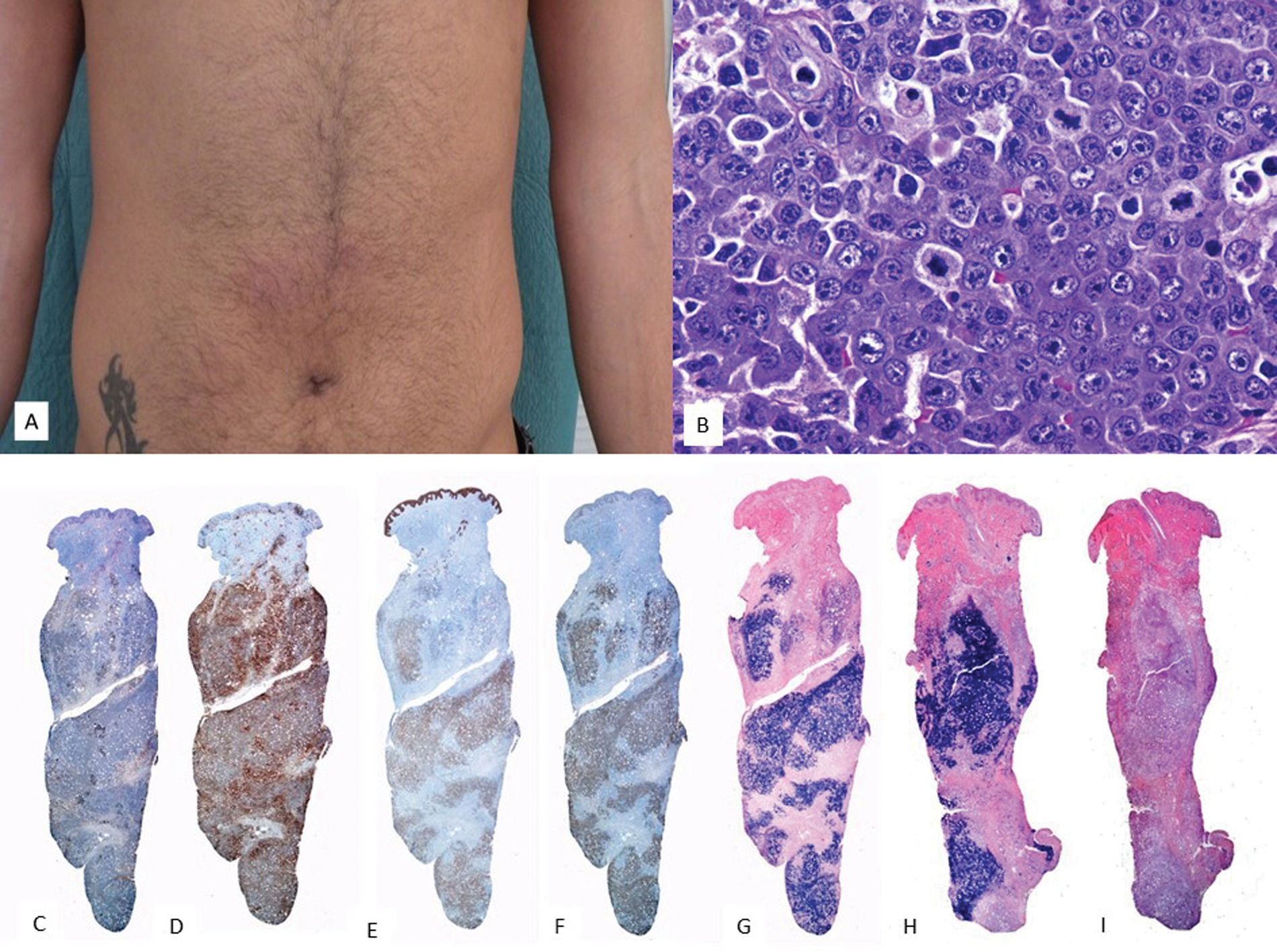

EBV+ extracavitary PEL. (A) Clinical image showing a subcutaneous mass with erythema on the periumbilical skin. (B) At higher magnification, the tumor infiltrate consists of large elements with a plasmablastic habit (H&E, 20×). The immunohistochemical study reveals that these cells are (C) negative for CD20 (2×) and (D) negative for CD3 (2×). Conversely, they show positivity for (E) CD138 (2×), (F) HHV8 (2×), and (G) EBER (2×), and (H) monotypic expression for kappa light chains (2×). (I) Lambda light chains (2×).

It presents diffuse infiltrates of large, pleomorphic cells with immunoblastic or plasmablastic features (Fig. 4). By definition it is HHV8+ and expresses latency-associated nuclear antigen (LANA). Although these tumor cells lack B-cell markers and germinal center markers such as CD10 and BCL6, they test positive for plasma cell markers such as MUM1, BLIMP1, CD38, and CD13856 (Fig. 4). MYC oncogene mutations are rare,56 unlike in PBL. EBV may be present.

Treatment updatesPolychemotherapy regimens like CHOP are used, along with antiretroviral therapy (ART), which is critically important, as poorer prognosis is observed in patients who do not use ART.56

Other LPDs with cutaneous involvementPost-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder with cutaneous involvementFrom a biological standpoint, nearly all EBV-related LPDs can occur during the state of immunosuppression after transplantation.60 The risk of developing these correlates with the level and duration of immunosuppression required for transplantation, as well as the recipient's age and EBV serostatus.19 EBV-naïve recipients who acquire the infection post-transplant are at the highest risk of developing PTLPD. Approximately 22% of PTLPD patients may have cutaneous involvement, most widely described after renal transplantation.61 Polymorphic PTLDs are, by definition, B-cell in origin and nearly all EBV+, while the term monomorphic can refer to various B- or T-cell lymphomas, which may or may not be EBV+. In the literature, cases of cutaneous PTLPDs present clinically as maculopapular lesions, nodules, or tumors, with or without associated ulceration.62 An unusual form of these cutaneous B-cell PTLPDs is EBV+ marginal zone lymphoma.63

Polymorphic EBV+ B-lymphoproliferative disorders, unspecifiedIntroduced in the 2022 ICC classification,3 this term is proposed for B-lymphoid proliferations with or without known immunodeficiency that do not fit into recognized entities. It can also be used when diagnostic certainty is hampered by small or low-quality biopsy samples.

EBV-related T-lymphoproliferative disorders and lymphomas with cutaneous involvementIn the skin, EBV+ T- or NK-cell LPDs are very rare, collectively accounting for <2% of primary cutaneous lymphomas,1 with higher incidence rates in Asian and Latin American populations, suggesting a possible genetic predisposition. Unlike EBV+ B-cell lymphomas, immunosuppression does not appear to play a significant role in the development of these lymphomas.64

Childhood EBV-related T/NK-lymphoproliferative disorders and lymphomasAccording to the 5th edition of the WHO classification2 and the ICC of mature lymphoid neoplasms,3 4 main groups are included within this family: hydroa vacciniforme-like lymphoproliferative disorder (HVLPD), severe mosquito bite allergy, chronic active EBV systemic disease (CAEBV), and systemic childhood EBV+ T-cell lymphoma. Notably, the first 3 have a risk of progressing to systemic lymphomas and/or hemophagocytic syndrome, making early diagnosis crucial. EBV viral load follow-up doesn’t seem to distinguish between clinical forms or prognostic outcomes.65 There is no standardized therapeutic approach for these entities. Sections below discuss those with cutaneous involvement.

Hydroa vacciniforme-like lymphoproliferative disorderThe concept and definition of HVLPD, introduced in the most recent classifications,2,3 have changed dramatically since this disease was first described in 1862.66 Initially considered a rare idiopathic and photosensitive skin disorder, it is now recognized as an EBV+ T- and NK-cell lymphoproliferative disorder with a wide spectrum of clinical aggression and course.

Epidemiology and pathogenesisWhile it is more prevalent among Asian or Latin American children and adolescents, isolated cases in adults and Caucasians have also been described.67 Clonal rearrangements of the T-cell receptor (TCR) are frequent, though they have no prognostic impact. On the other hand, targeted genetic studies to identify driver mutations in this entity have been limited, but recent reports indicate mutations in STAT3, IKBKB, ELB, CHD7, and KMT2D.68 These findings require validation in larger cohorts. Another case has been associated with a DOCK8 gene mutation.69

Clinical featuresTwo clinical forms are recognized, different in disease course and prognosis.14 The classic form behaves as a benign, self-limiting disease that spontaneously remits during adolescence. It predominantly affects white patients and is characterized by the absence of systemic symptoms. Typical papulovesicular eruptions occur on sun-exposed skin and resolve with photoprotection.70 The systemic form, initially described as “angiocentric T-cell lymphoma of childhood”,71 is more common among Asians and Hispanics. Patients may develop lesions on both sun-exposed and non-exposed skin, with a more prolonged disease course and more severe skin lesions vs the classic form. These can be accompanied by systemic symptoms and progression to lymphoma. In one of the earliest published series, 4 male children aged 3–12 years presented with persistent facial edema, necrosis, and valioliform scars (Fig. 5).72 Subsequent series have identified a broader spectrum of clinical presentations.72–78 Atypical presentations, such as periorbital or ocular involvement with swelling, marked edema, and conjunctival congestion have been associated with very poor outcomes.75,79,80 Another rare sign is oral mucosal involvement.81

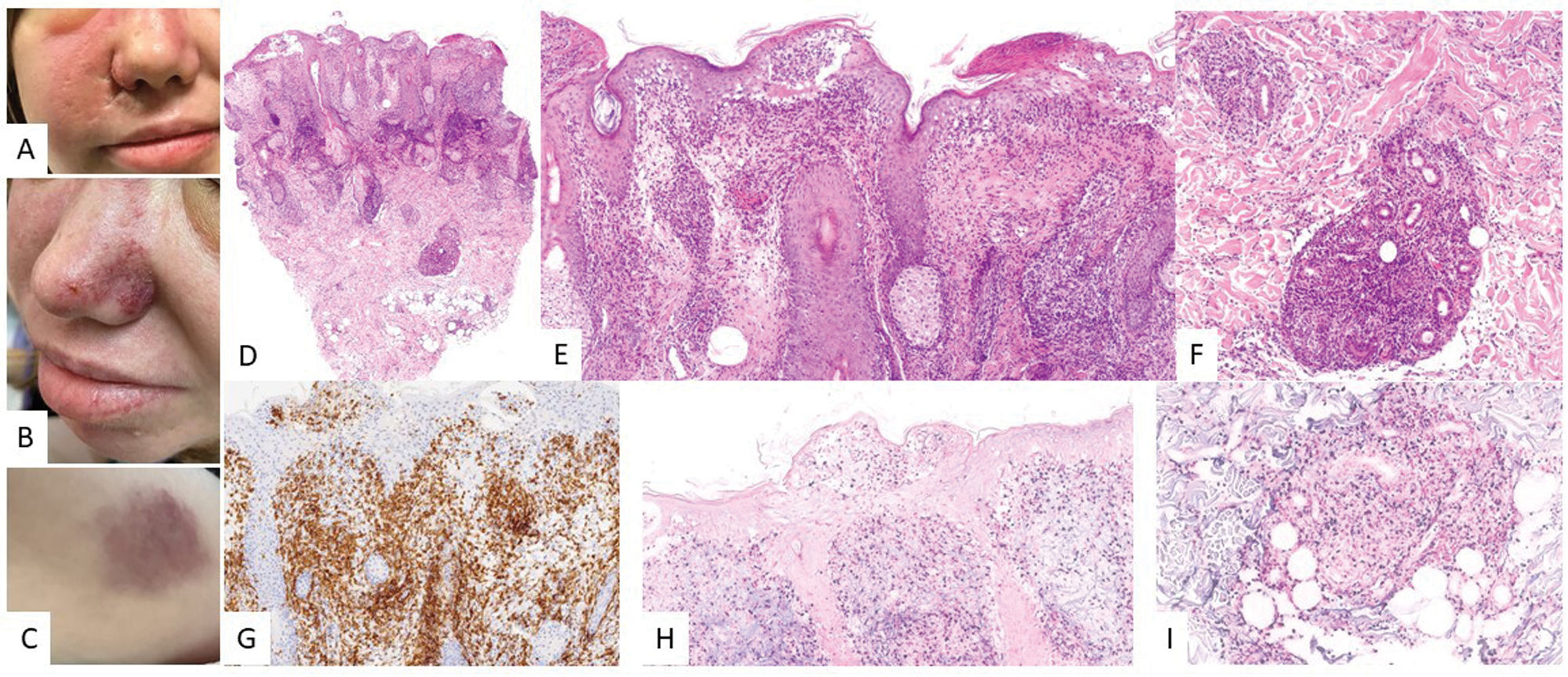

Hydroa vacciniforme-like lymphoproliferative disorder. (A–C) Clinical images of a patient's face showing significant malar edema and lesions in the form of erythematous–violaceous plaques, along with small varioliform scars from previous lesions. (D–F) H&E, 2× and 10×. At low magnification, a skin punch shows superficial and deep lymphoid infiltration with epidermotropism. At higher magnification, spongiotic vesicles with keratinocyte necrosis are observed (E), and perianexial infiltrates (F). Tumor population is positive for CD2 (G, 10×) and EBER (H and I, 10×).

Various histological patterns have been described.73 Some cases exhibit intraepidermal spongiotic vesiculation with necrosis of the epidermis. Others display periadnexal infiltrates or a combination of both (Fig. 5). Angiodestructive patterns are not always present and cannot be considered a sine qua non diagnostic feature.72,74 Neural infiltration by tumor cells has also been reported.71 Subcutaneous tissue involvement in some cases may lead to differential diagnosis with subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma.67 Cytomorphological features include infiltrates that may be monomorphic, composed of small-to-medium sized lymphocytes, or heterogeneous, with atypical lymphocytes intermixed with reactive elements such as histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils. Immunohistochemically, neoplastic cells exhibit a cytotoxic T/NK phenotype, expressing EBER, TIA-1, granzyme B, and perforin (Fig. 5). Most cells are CD8+, though CD4+, CD4/CD8+, or NK phenotypes have been reported as well. The latter may mimic panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma.14 CD30 is frequently expressed, and some authors suggest its expression may correlate with a more aggressive clinical course.71,82 Expression of PD-L1 has been poorly studied, with a few positive cells among the infiltrates, mainly corresponding to small reactive lymphocytes.67

Treatment updatesIn mild forms, some patients have responded to antiviral therapy.83,84 In advanced cases, immunotherapy or chemotherapy may play a role, although AHSCT remains the only curative treatment.

Severe mosquito bite allergyThe concept and definition of severe mosquito bite allergy have not changed in recent classification updates.

Epidemiology and pathogenesisThis is a very rare NK-cell EBV+ LPD. As it happens with HVLPD, the etiology is unknown. At molecular level, no specific changes have been identified in this condition, as no targeted studies have been conducted to this date.

Clinical featuresIt is characterized by high fever and local skin symptoms following a mosquito bite, presenting as erythema, blisters, ulcers, or necrosis, which leave deep scars.85 Patients show elevated serum IgE levels, high EBV DNA titers, and increased NK cells in peripheral blood. Although it is typically self-limiting, there is an increased risk of developing hemophagocytic syndrome and/or progressing to systemic NK/T-cell lymphoma or aggressive NK-cell leukemia.

HistologyMicroscopically, skin lesions resemble HVLPD, with more extensive local necrosis and a higher frequency of angiodestruction. The infiltrate is more polymorphic, with lymphocytes of varying sizes—some of them atypical—along with histiocytes and abundant eosinophils. Cells have an NK-cell phenotype, expressing CD3ɛ, CD56, TIA-1, granzyme B, and perforin.

Treatment updatesThere is no standard treatment. Omalizumab has shown efficacy in preventing anaphylactic episodes in a patient with severe mosquito bite allergy.86

Chronic active EBV diseaseThis entity has been renamed in the latest classifications of lymphoid neoplasms, replacing “infection” with “disease” (WHO 5th edition and ICC 2022),2,3 considering that only a small proportion of individuals with chronic active EBV infection develop the disease (Annex).

Epidemiology and pathogenesisIts incidence is also higher among Asian populations and individuals native to Central and South America. At molecular level, recurrent somatic mutations have been identified in DDX3X, KMT2D, BCOR/BCORL1, KDM6A, and TET2. In the largest study conducted on 83 cases of CAEBV, at least 1 of these mutations was present in 58% of cases. Of particular interest are mutations in DDX3X, also identified in other lymphomas, suggesting that acquiring mutations in this gene may initiate lymphomagenesis. Another group has reported the presence of intragenic deletions in BamHI as well as in other genes needed to produce viral particles. These deletions are hypothesized to be related to the reactivation of the lytic cycle, preventing viral production and cell lysis. Finally, some patients have shown minor defects in cellular immunity that may alter the role of EBV-infected T/NK cells in recognizing exogenous antigens.87

Clinical featuresThis is a condition persisting for 3 or 4 months, during which patients show elevated levels of EBV DNA in peripheral blood and tissue infiltration by EBV-infected T/NK lymphocytes in the absence of immunodeficiency. Approximately half of the patients exhibit symptoms similar to infectious mononucleosis, such as fever, lymphadenopathy, and hepatosplenomegaly. Clinical course is variable but prolonged, and in most cases, disease progresses. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis is a complication with a poor prognosis.

HistologySkin involvement is variable, ranging from presentations resembling severe mosquito bite allergy to HV-like signs, making histological studies of the lesions nonspecific. Cases in the form of panniculitis have also been reported.88,89

Treatment updatesPrognosis for patients with CAEBV is poor, and advanced age at presentation seems to be an adverse prognostic factor. Treatment must address both the inflammatory and tumoral processes and should be initiated before disease progresses to lymphoma or hemophagocytic syndrome. The only curative treatment is hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and the role of chemotherapy is limited to reducing the disease burden prior to transplantation. Given the activation of STAT3 in this disease, the efficacy profile of ruxolitinib has been tested in a clinical trial with promising results.90

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphomaIn the latest classifications of lymphoid neoplasms (WHO 5th edition and ICC 2022), the “nasal type” designation has been removed from this entity (Annex).

Epidemiology and pathogenesisUnlike pediatric NK/T-cell lymphomas and LPDs, this lymphoma almost exclusively affects adults, with a mean age of 44–54 years and a male-to-female ratio of 2–3:1. Although the exact role of EBV in the pathogenesis of the disease is unknown, EBV positivity is considered essential for diagnosis. On the other hand, multiple genetic alterations have been described in this type of lymphoma, with 6q21-25 deletion being the most common one. This region harbors various tumor suppressor genes, such as PRDM1, PTPRK, FOXO3, and HACE1. Other recurrent alterations include gains in 1q21-q44, 2q, and 7q, and losses in 17p15-22. Additionally, gene expression studies have also highlighted dysregulation in various oncogenic pathways (cell cycle/apoptosis, NF-κB, NOTCH, and JAK/STAT) and alterations in individual genes (MYC, RUNX3, and EZH2). Recently, mutations in epigenetic regulators, such as PRDM1, BCOR, DDX3X, STAT3, and TP53, have been identified.87,91

Clinical featuresInvolvement of the nasal cavity, nasopharynx, or the upper aerodigestive tract is characteristic, presenting as ulcerative, destructive lesions with bone erosion. Extranasal forms are much less common, with the most frequently involved organs being the skin, the GI tract, testes, and soft tissues. Skin lesions are usually found in the lower extremities as multiple nodules with necrotic ulcerative centers (Fig. 5A). Occasionally, they mimic panniculitis-like lesions. Prognosis is poor, and the disease is typically diagnosed in advanced stages.

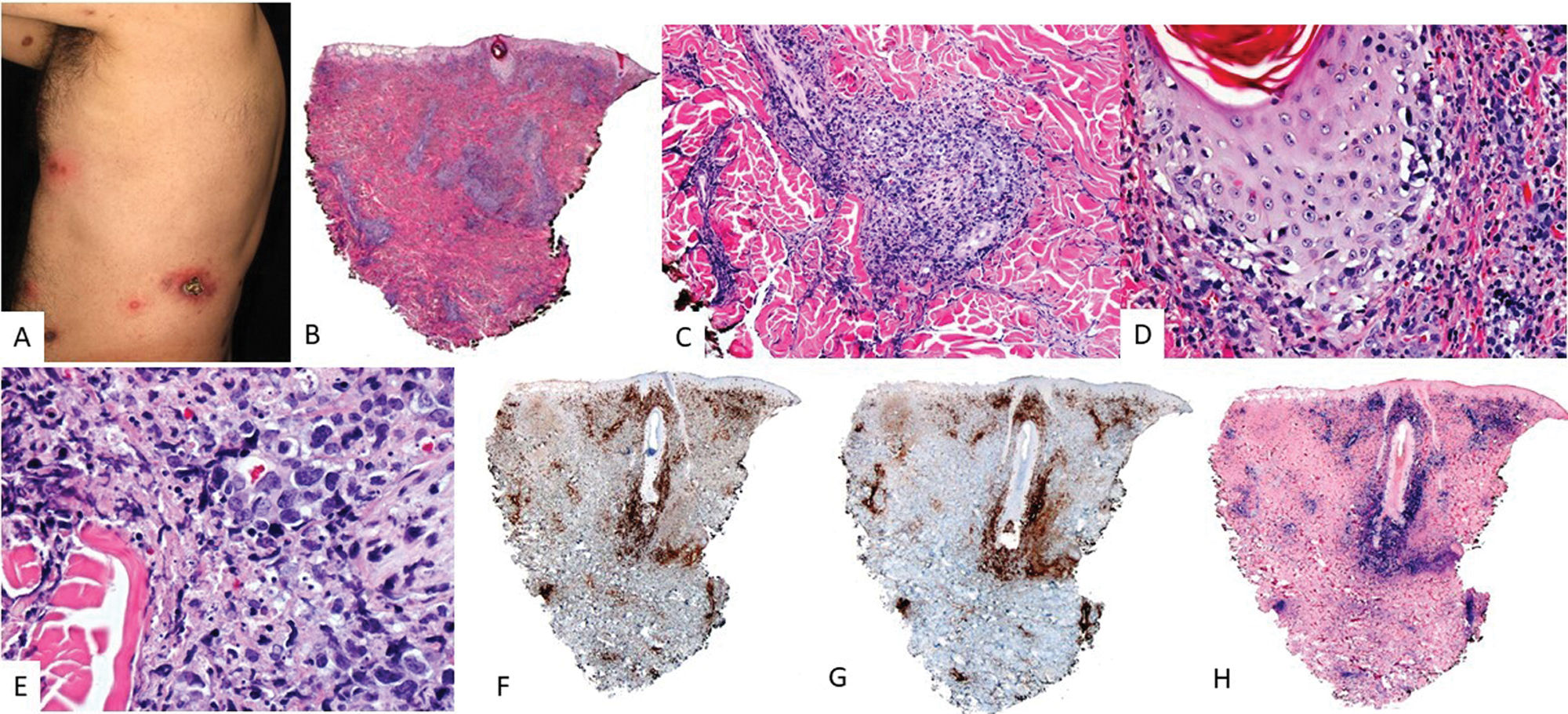

HistologyIn the skin, dermal involvement can be observed, with infiltration being interstitial or nodular (Fig. 6). Tumor cells are medium to large in size, distributed around blood vessels, infiltrating and destroying vessel walls. This is associated with fibrinoid necrosis, elastic lamina fragmentation, and thrombosis (Fig. 6). These infiltrates may extend into subcutaneous tissue, mimicking panniculitis-like inflammatory processes.

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma. (A) Clinical image shows multiple nodules with necrotic centers and erythematous halos distributed on the trunk. (B) (H&E, 2×): At low magnification, a dermal infiltrate is observed in the superficial and deep portions, related to vessels (C, 4×) and adnexa with epidermotropism (D, 10×). At higher magnification (E, 20×), the infiltrate is composed of large atypical elements. These cells are positive for CD3 (F, 2×), CD56 (G, 2×), and EBER (H, 2×).

Tumor cells exhibit a T/NK-cell phenotype, with positivity for CD56, CD3ɛ, and CD2, as well as variable positivity for FAS, FASL, CD25, CD38, and CD30. Conversely, these cells lack surface CD3, CD4, and CD5 expression. In a small percentage of cases, the tumor population shows a cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell phenotype with monoclonal TCR rearrangements.

Treatment updatesL-asparaginase-based chemotherapy is the gold standard here; however, response is generally poor. Other therapeutic targets in the pipeline include PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors and drugs modulating the JAK/STAT and NF-κB pathways.87

Primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma with a follicular center phenotypeThis is a poorly characterized entity with little correspondence to previously described conditions and recently included as a separate entity in the 5th WHO classification (Annex). According to the largest series, these cases seem to share biological features with nodal T-cell lymphomas of centrofollicular phenotype.92 Very few published cases are EBV+,93 and they seem to have a worse prognosis and a more aggressive clinical course. Despite the limited case reports, they are mentioned in this review to inform readers and highlight their importance in the differential diagnosis with cutaneous involvement of angioimmunoblastic-type T-follicular helper (TFH) cell lymphoma.

Epidemiology and pathogenesisA higher prevalence in men has been reported, with a median age at presentation of 67 years. At molecular level, mutations in RHOA and TET2 are the most common alterations. In most cases, clonal rearrangement is detected.

Clinical featuresOn the skin, multiple nodules or papules appear—often as isolated disease—but with the potential to progress into systemic lymphoma.

HistologyVarious patterns have been described, ranging from dense and deep infiltrates to superficial band-like involvement or even a perivascular pattern. Cytologically, infiltrates consist of intermediate to large lymphocytes with irregular nuclei. Phenotypically, tumor cells are T-cells, expressing CD4 and variably showing positivity for Bcl6, CD10, CXCL13,and PD1. EBER-positive cases can be easily distinguished from other entities described in this manuscript based on the phenotype of tumor cells and their clinical presentation. In this case, the main differential diagnosis is with cutaneous involvement by angioimmunoblastic-type T-follicular helper (TFH) cell lymphoma.

Treatment updatesClinical management varies depending on the case. Most patients receive chemotherapy. Cases with molecular alterations similar to those of angioimmunoblastic-type T-follicular helper (TFH) cell lymphomamay benefit from new targeted therapies, such as histone deacetylase inhibitors and hypomethylating agents.

Intravascular NK/T-cell lymphomaSince its initial description in 1959 as angioendotheliomatosis proliferans systemisata, less than 30 cases have been published.91,94–99 Unlike intravascular B-cell lymphoma, it is not currently considered a distinct entity, and it remains controversial whether it represents a form of aggressive NK leukemia or extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma.91

Epidemiology and pathogenesisDescribed molecular alterations suggest a multifactorial etiopathogenesis involving genes related to epigenetic regulation91: histone genes (HIST1H2AN, HIST1H2BE, HIST1H2BN, H3F3A) and methylation-related genes (TET2and DNMT1). Additionally, some data suggest involvement in the alternative splicing process (HRAS, MDM2, VEGFA). Finally, some cases have demonstrated strong PD1 expression, which may be related to EBV infection.100

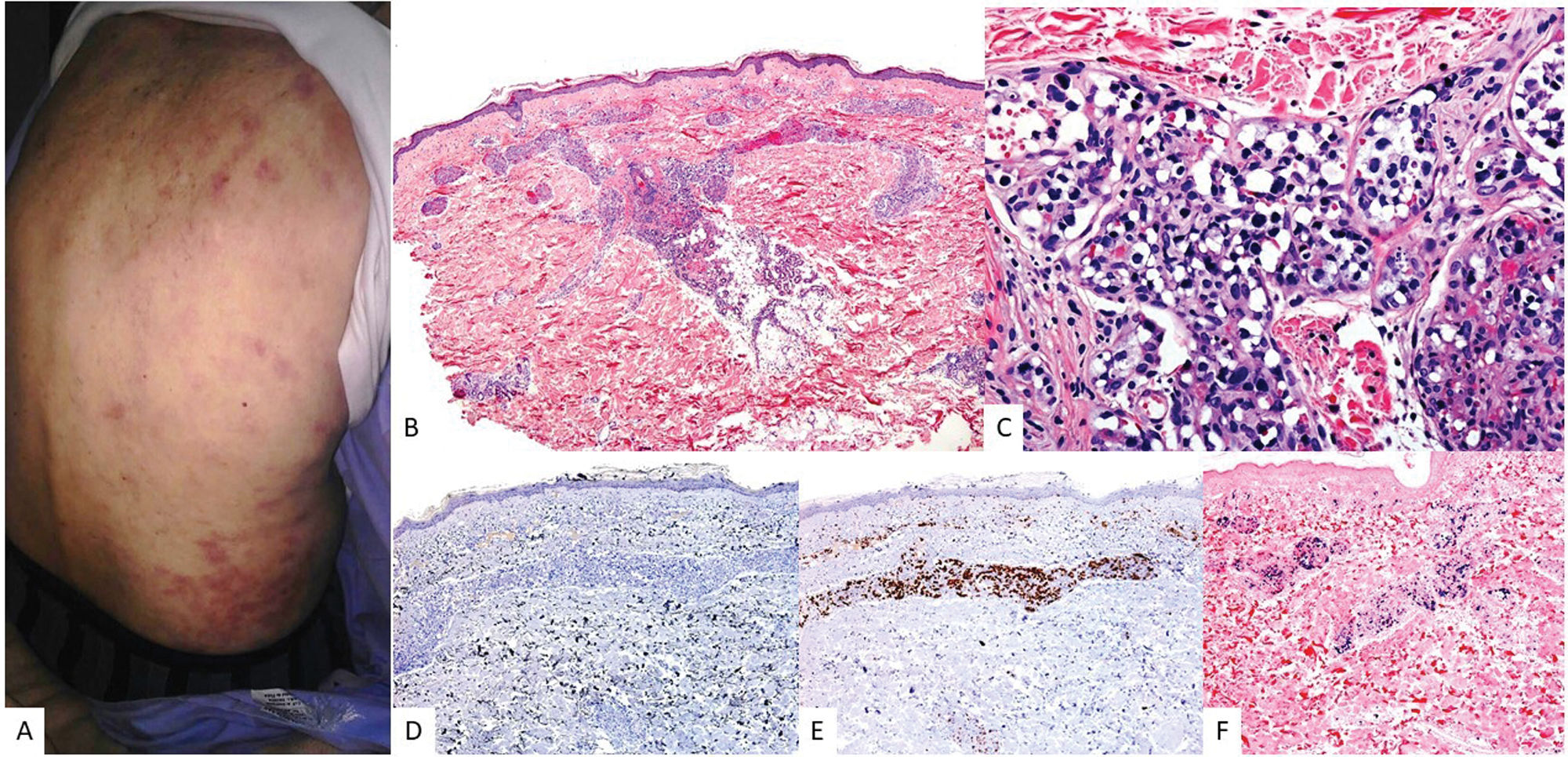

Clinical featuresIn addition to the CNS, the skin is one of the most widely affected organs. While it has been suggested that cases with exclusive cutaneous involvement may have a better prognosis than those with multiple organ involvement,96 the differences are not statistically significant, and it is still considered an aggressive disease with poor response to chemotherapy. On the skin, it presents nonspecifically as erythematous–violaceous patches or plaques on the trunk and extremities (Fig. 7A).

Cutaneous intravascular NK/T-cell lymphoma. (A) Clinical image shows multiple ecchymotic macules and plaques distributed on the trunk, some with a linear or grouped distribution. (B) (H&E, 2×): At low magnification, a dermal infiltrate involving the superficial and deep vessel plexuses is observed. At higher magnification (C, 10×), the infiltrate is located within the vessels and consists of large atypical elements with marked nuclear hyperchromatism. Although these cells are negative for CD20 (D, 4×), they are positive for CD3 (E, 4×) and EBER (F, 4×).

It is characterized by proliferation—confined to the lumens of vessels—of intermediate to large lymphoid cells of T/NK phenotype, with EBV presence (EBER+) (Fig. 7B–F).

Treatment updatesCurrently, there is no standardized chemotherapy regimen, although it seems clear that traditional CHOP regimens are insufficient.

Conflicts of interestAuthor Lucía Prieto has participated in training provided by Kiowa and Takeda. The remaining authors declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

Uncited reference101.

We wish to thank Dr. Socorro María Rodríguez Pinilla for her contribution to the images in Figs. 2, 3, 5 and 6.