Despite advances made in treatments for atopic dermatitis (AD), information on its impact and interaction with atopic comorbidities, such as asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, and ocular disease is limited. This study aims to assess the clinical–epidemiological characteristics of patients with AD – treatment response included – while taking into consideration atopic comorbidities like these.

Materials and methodsData were analyzed from the multicenter BIOBADATOP registry (a prospective cohort of AD patients initiating systemic treatment). We conducted a descriptive analysis of the main characteristics collected in the registry in relation to atopic comorbidity.

ResultsWe included a total of 509 patients, mostly adults (81.9%) with severe AD (73.7%). Patients with personal atopic comorbidity (64%) more frequently exhibited flexural dermatitis (89.7% vs. 81.5%), a higher mean of previous systemic treatments (1.6 vs. 1.3), and higher baseline values on the POEM scale (19.6 vs. 17.9). Patients with familial atopic comorbidity (40.7%) had a higher incidence of pediatric/adolescent patients (24.2% vs. 13.9%) and a history of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis (61.1% vs. 47.1%). No differences regarding treatment response were observed at the 6- and 12-month follow-ups based on the presence or absence of atopic comorbidities.

ConclusionsResults suggest that a history of atopic comorbidity is associated with an early onset and persistent course of AD. Although no differences were reported in the short-term treatment response, further follow-up is required to better understand the impact of comorbidities on AD.

Pese al avance terapéutico en la dermatitis atópica (DA), la información sobre el impacto y la interacción con las comorbilidades atópicas (como el asma, la rinoconjuntivitis y la afección ocular) es limitada. Este estudio pretende evaluar las características clínicas y epidemiológicas de los pacientes con DA, así como la respuesta al tratamiento, considerando dichas comorbilidades.

Material y métodosSe realizó un análisis descriptivo de los datos del registro multicéntrico BIOBADATOP, una cohorte prospectiva de los pacientes con DA, que inician tratamiento sistémico, según la comorbilidad atópica.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 509 pacientes, siendo mayoritariamente adultos (81,9%), con DA grave (73,7%). Los pacientes con comorbilidad atópica personal (64%) presentaron con mayor frecuencia dermatitis flexural (89,7 vs. 81,5%), mayor media de tratamientos sistémicos utilizados (1,6 vs. 1,3) y valores basales mayores en la escala POEM (19,6 vs. 17,9). Entre los pacientes con comorbilidad atópica familiar (40,7%) hubo mayor número de pacientes pediátricos/adolescentes (24,2 vs. 13,9%) y con antecedente de rinoconjuntivitis alérgica (61,1 vs. 47,1%). No se observaron diferencias en la respuesta a los tratamientos a los 6 y 12 meses, en función de la presencia o ausencia de comorbilidades atópicas.

ConclusionesLos resultados sugieren que el antecedente de comorbilidad atópica se asocia con inicio temprano y curso persistente de la DA. Aunque no se observaron diferencias en la evolución a corto plazo, se destaca la necesidad de mayor seguimiento para comprender mejor el impacto de las comorbilidades en la DA.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by recurrent and unpredictable episodes of eczematous lesions. While symptoms commonly appear before the age of six, it is not uncommon for the disease to begin in adulthood, highlighting the variability of its clinical presentation.1 AD affects approximately 15% of the pediatric population in developed countries2,3 and is closely related to the concept of atopic status, which includes various conditions such as food allergies, asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eosinophilic esophagitis. The interconnection among these conditions suggests a genetic basis and an altered immune response as key factors in the development and persistence of AD.4,5

The prevalence of rhinitis and/or asthma in individuals with AD is estimated at 40.5% (25.7% for rhinitis and 14.2% for asthma),6 though significant variations may occur depending on the age at which the condition is assessed.7 Nationwide, results from the EpiChron cohort3 indicate that the most common chronic comorbidities in the pediatric population with AD were asthma (13.1%), psychosocial disorders (7.9%), visual impairment (7.8%), congenital limb anomalies (5.8%), and developmental disorders (3.2%), among others. Additionally, different published cohorts have shown that individuals with more severe clinical presentations of AD are at higher risk of developing comorbidities, which tend to show with greater intensity,6,8 which underscores the importance of adequately screening for associated comorbidities in these patients for optimal overall management of AD.9

In addition to the impact of skin lesions and comorbidities, persistent pruritus and the associated pain can lead to sleep disorders, anxiety, and/or depression, exacerbating the emotional burden on affected individuals. The need for a comprehensive approach becomes evident once again to provide complete care and improve the quality of life for those living with AD.10

In recent years, advancements in AD treatment have emerged, thanks to the introduction of innovative therapies with diverse mechanisms of action.11 These new therapeutic options open the possibility of extending beneficial effects to atopic comorbidities. However, the safety profile of these treatments may be influenced by the presence of such comorbidities.12,13

Despite these advancements, limited information exists on the effect and interaction of new treatments with atopic comorbidities. Most information comes from randomized clinical trials supporting the commercial approval of drugs. While these trials are crucial for understanding the expectations of drug efficacy, they include selection criteria that do not always reflect the diversity of patients encountered in the routine clinical practice. Patients with severe comorbidities are often excluded.

In this context, registries collecting data from patients from the routine clinical practice become particularly valuable. These registries not only complement the evidence from clinical trials but also provide a broader and more representative perspective on the safety and efficacy profile of treatments in real-world conditions.14

The present study aims to describe the clinical and epidemiological characteristics of patients with AD, as well as their treatment responses, based on the presence or absence of atopic comorbidities and family history of atopic comorbidities.

Materials and methodsThe study included patients from the Spanish Registry of Atopic Dermatitis (BIOBADATOP), which has already been previously described.14 Briefly, it is a prospective, multicenter observational cohort that, since its inception in March 2020, includes pediatric, adolescent, and adult patients with AD initiating systemic immunomodulatory therapy. Baseline visits collect demographic data, diagnostic information, and disease severity metrics using the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), and the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM). Similarly, data on comorbidities and prior treatments are recorded. Follow-up visits document changes in AD severity, main systemic treatments, and any concomitant treatments. Adverse events, if any, are recorded using the MedDRA dictionary.

Patient data mining in the registry is conducted using a pseudonymized unique identification code, employing the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) online system.

We conducted a descriptive analysis of patients included from the start of the registry (March 2020) to the current cutoff (September 2023) based on the presence or absence of atopic comorbidities, which were defined as either the patient exhibiting asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, or atopic ocular disease, or having a first-degree relative with AD, asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, or atopic ocular disease.

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata software (version 17.0, StataCorp, Texas, United States). Demographic and clinical data were described using conventional statistics (means and standard deviations, absolute and relative frequencies). Differences across groups were compared using the chi-square test, Student's t-test, or the Mann–Whitney test, as appropriate. Box plots illustrated treatment responses at 6 and 12 months based on the presence or absence of atopic comorbidity. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The BIOBADATOP registry received approval from the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Aragón (Spain) (PA18/051). This approval process adheres to the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki and complies with current ethical and clinical research legislation. All patients provided written consent to be included in the study.

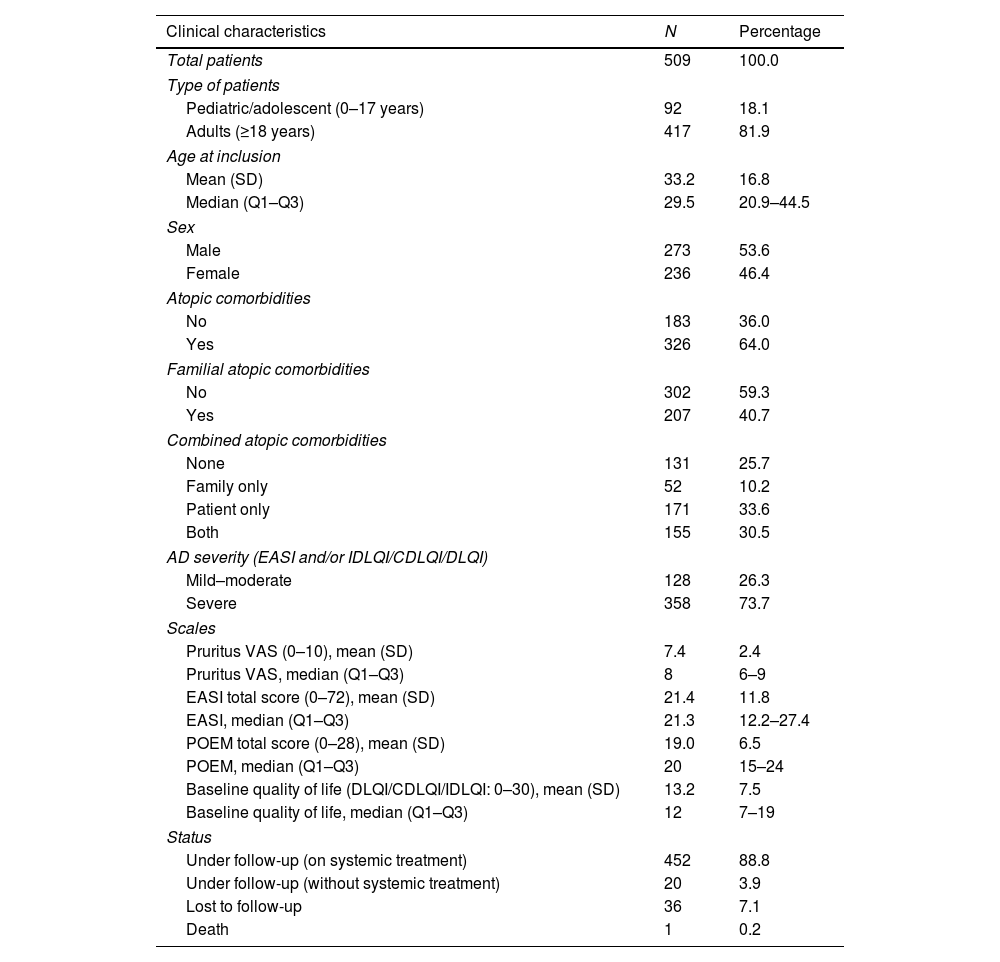

ResultsClinical characteristics of study patientsIn the present study, a total of 509 patients with AD were included from the BIOBADATOP registry. Most patients were adults (81.9%), with a median age of 29.5 years and an interquartile range of 20.9–44.5 years. The registry median follow-up time at the time of the cutoff was 9.6 months (IQR, 4.8–21.6 months). A total of 73.7% of the patients presented severe AD vs. 26.3% with mild or moderate AD. Additionally, 64% of the patients included in the registry had personal atopic comorbidities and 40.7%, familial atopic comorbidities. More clinical characteristics of the patients included in the study are shown in Table 1.1

Clinical characteristics of patients included in the study.

| Clinical characteristics | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Total patients | 509 | 100.0 |

| Type of patients | ||

| Pediatric/adolescent (0–17 years) | 92 | 18.1 |

| Adults (≥18 years) | 417 | 81.9 |

| Age at inclusion | ||

| Mean (SD) | 33.2 | 16.8 |

| Median (Q1–Q3) | 29.5 | 20.9–44.5 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 273 | 53.6 |

| Female | 236 | 46.4 |

| Atopic comorbidities | ||

| No | 183 | 36.0 |

| Yes | 326 | 64.0 |

| Familial atopic comorbidities | ||

| No | 302 | 59.3 |

| Yes | 207 | 40.7 |

| Combined atopic comorbidities | ||

| None | 131 | 25.7 |

| Family only | 52 | 10.2 |

| Patient only | 171 | 33.6 |

| Both | 155 | 30.5 |

| AD severity (EASI and/or IDLQI/CDLQI/DLQI) | ||

| Mild–moderate | 128 | 26.3 |

| Severe | 358 | 73.7 |

| Scales | ||

| Pruritus VAS (0–10), mean (SD) | 7.4 | 2.4 |

| Pruritus VAS, median (Q1–Q3) | 8 | 6–9 |

| EASI total score (0–72), mean (SD) | 21.4 | 11.8 |

| EASI, median (Q1–Q3) | 21.3 | 12.2–27.4 |

| POEM total score (0–28), mean (SD) | 19.0 | 6.5 |

| POEM, median (Q1–Q3) | 20 | 15–24 |

| Baseline quality of life (DLQI/CDLQI/IDLQI: 0–30), mean (SD) | 13.2 | 7.5 |

| Baseline quality of life, median (Q1–Q3) | 12 | 7–19 |

| Status | ||

| Under follow-up (on systemic treatment) | 452 | 88.8 |

| Under follow-up (without systemic treatment) | 20 | 3.9 |

| Lost to follow-up | 36 | 7.1 |

| Death | 1 | 0.2 |

AD: atopic dermatitis; CDLQI: Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index; DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; EASI: Eczema Area Severity Index; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale; IDLQI: Infant's Dermatology Life Quality Index; POEM: Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure; Q1: first quartile; Q3: third quartile; SD: standard deviation.

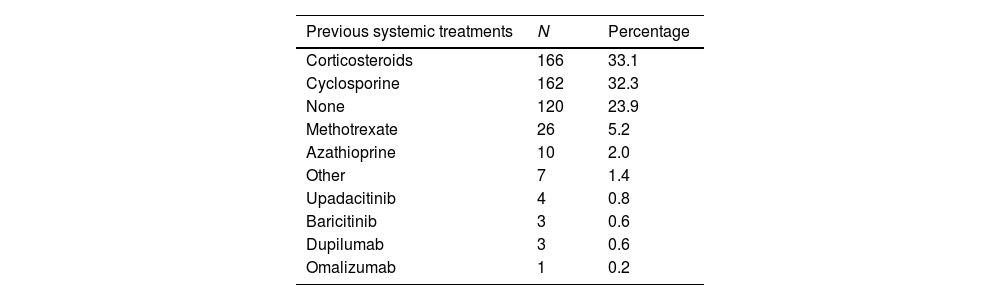

The most common presentations of AD were flexural dermatitis (86.8%), followed by facial-eyelid dermatitis (84.4%) and hand dermatitis (60.1%). Regarding treatments prior to registry inclusion, the most widely used were oral corticosteroids (33.1%) and cyclosporine (32.3%). Notably, 23.9% of the patients had not used any prior treatment.

A total of 749 systemic treatments were initiated, with dupilumab (37.1%) and cyclosporine (29.2%) being the most common ones. Additionally, 532 topical therapies were recorded, with topical corticosteroids (50.4%) being the most widely used. For a more detailed overview of the systemic and topical treatments used, see Table 2.

Systemic and topical therapues used at the follow-up.

| Previous systemic treatments | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Corticosteroids | 166 | 33.1 |

| Cyclosporine | 162 | 32.3 |

| None | 120 | 23.9 |

| Methotrexate | 26 | 5.2 |

| Azathioprine | 10 | 2.0 |

| Other | 7 | 1.4 |

| Upadacitinib | 4 | 0.8 |

| Baricitinib | 3 | 0.6 |

| Dupilumab | 3 | 0.6 |

| Omalizumab | 1 | 0.2 |

| Initiated systemic treatments | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Dupilumab | 278 | 37.1 |

| Cyclosporine | 219 | 29.2 |

| Upadacitinib | 89 | 11.8 |

| Corticosteroids | 56 | 7.4 |

| Tralokinumab | 55 | 7.3 |

| Baricitinib | 19 | 2.5 |

| Methotrexate | 17 | 2.2 |

| Abrocitinib | 11 | 1.4 |

| Omalizumab | 1 | 0.1 |

| Other | 4 | 0.5 |

| Initiated topical therapies | N | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Corticosteroids | 490 | 50.4 |

| None | 441 | 45.3 |

| Calcineurin inhibitors | 37 | 3.8 |

| Other | 5 | 0.5 |

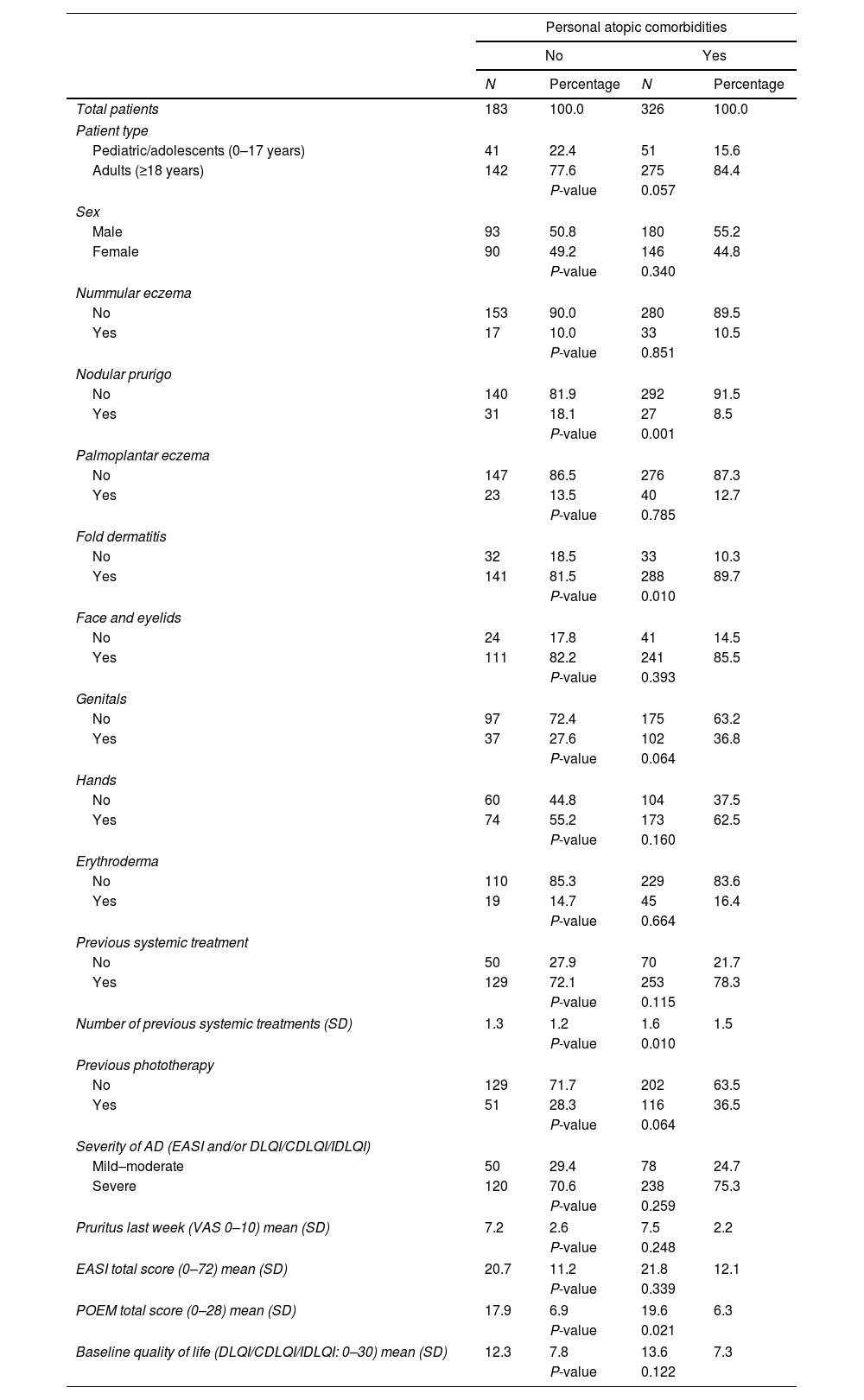

Patients with atopic comorbidities were more likely to exhibit flexural dermatitis as a clinical form (89.7% vs. 81.5%; P=0.010), less likely to exhibit nodular prurigo (8.5% vs. 18.1%; P=0.001), had used more systemic therapies previously (1.6 vs. 1.3; P=0.010), and had higher baseline POEM scores (19.6 vs. 17.9; P=0.021) vs. those without atopic comorbidities.

No significant differences were reported between the presence or absence of atopic comorbidities and other clinical forms of AD, baseline EASI severity, quality of life, or the EVA Pruritus scale (Table 3). Similarly, no other differences were reported in the initiation of systemic therapies, whether first- or second-line therapies.

Comparison of clinical characteristics of patients based on the presence or absence of personal atopic comorbidities.

| Personal atopic comorbidities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| N | Percentage | N | Percentage | |

| Total patients | 183 | 100.0 | 326 | 100.0 |

| Patient type | ||||

| Pediatric/adolescents (0–17 years) | 41 | 22.4 | 51 | 15.6 |

| Adults (≥18 years) | 142 | 77.6 | 275 | 84.4 |

| P-value | 0.057 | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 93 | 50.8 | 180 | 55.2 |

| Female | 90 | 49.2 | 146 | 44.8 |

| P-value | 0.340 | |||

| Nummular eczema | ||||

| No | 153 | 90.0 | 280 | 89.5 |

| Yes | 17 | 10.0 | 33 | 10.5 |

| P-value | 0.851 | |||

| Nodular prurigo | ||||

| No | 140 | 81.9 | 292 | 91.5 |

| Yes | 31 | 18.1 | 27 | 8.5 |

| P-value | 0.001 | |||

| Palmoplantar eczema | ||||

| No | 147 | 86.5 | 276 | 87.3 |

| Yes | 23 | 13.5 | 40 | 12.7 |

| P-value | 0.785 | |||

| Fold dermatitis | ||||

| No | 32 | 18.5 | 33 | 10.3 |

| Yes | 141 | 81.5 | 288 | 89.7 |

| P-value | 0.010 | |||

| Face and eyelids | ||||

| No | 24 | 17.8 | 41 | 14.5 |

| Yes | 111 | 82.2 | 241 | 85.5 |

| P-value | 0.393 | |||

| Genitals | ||||

| No | 97 | 72.4 | 175 | 63.2 |

| Yes | 37 | 27.6 | 102 | 36.8 |

| P-value | 0.064 | |||

| Hands | ||||

| No | 60 | 44.8 | 104 | 37.5 |

| Yes | 74 | 55.2 | 173 | 62.5 |

| P-value | 0.160 | |||

| Erythroderma | ||||

| No | 110 | 85.3 | 229 | 83.6 |

| Yes | 19 | 14.7 | 45 | 16.4 |

| P-value | 0.664 | |||

| Previous systemic treatment | ||||

| No | 50 | 27.9 | 70 | 21.7 |

| Yes | 129 | 72.1 | 253 | 78.3 |

| P-value | 0.115 | |||

| Number of previous systemic treatments (SD) | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.5 |

| P-value | 0.010 | |||

| Previous phototherapy | ||||

| No | 129 | 71.7 | 202 | 63.5 |

| Yes | 51 | 28.3 | 116 | 36.5 |

| P-value | 0.064 | |||

| Severity of AD (EASI and/or DLQI/CDLQI/IDLQI) | ||||

| Mild–moderate | 50 | 29.4 | 78 | 24.7 |

| Severe | 120 | 70.6 | 238 | 75.3 |

| P-value | 0.259 | |||

| Pruritus last week (VAS 0–10) mean (SD) | 7.2 | 2.6 | 7.5 | 2.2 |

| P-value | 0.248 | |||

| EASI total score (0–72) mean (SD) | 20.7 | 11.2 | 21.8 | 12.1 |

| P-value | 0.339 | |||

| POEM total score (0–28) mean (SD) | 17.9 | 6.9 | 19.6 | 6.3 |

| P-value | 0.021 | |||

| Baseline quality of life (DLQI/CDLQI/IDLQI: 0–30) mean (SD) | 12.3 | 7.8 | 13.6 | 7.3 |

| P-value | 0.122 | |||

CDLQI: Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index; DA: atopic dermatitis; SD: standard deviation; DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; EASI: Eczema Area Severity Index; VAS: Visual Analog Scale; IDLQI: Infant's Dermatology Life Quality Index; POEM: Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure.

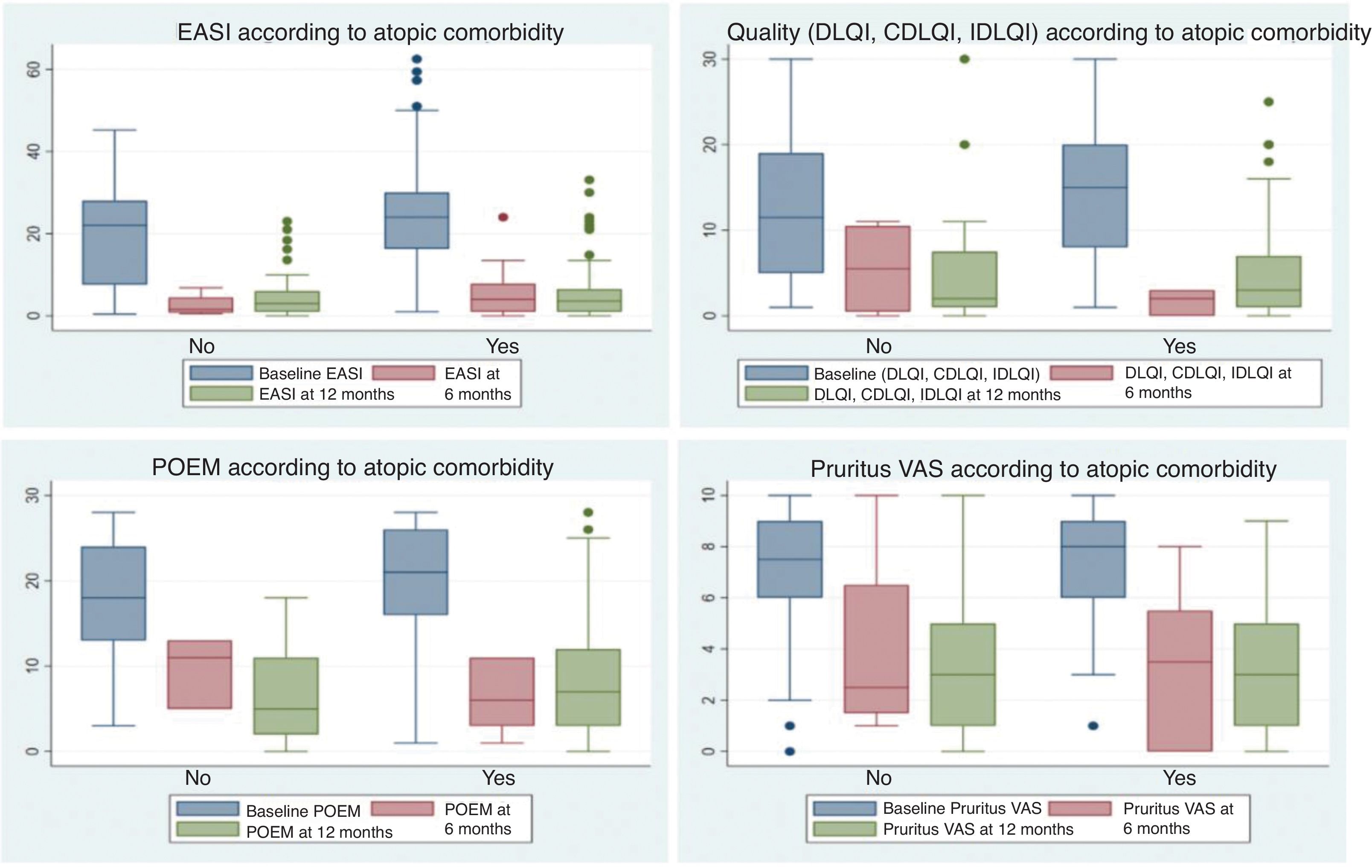

Finally, no differences were identified regarding personal atopic comorbidity histories in terms of discontinuation of the drugs prescribed first or later on, reasons for discontinuation or change, dosages used, or responses to systemic therapies at the 6- and 12-month follow-up (Fig. 1).4

Box plots showing response to systemic treatments at 6 and 12 months, based on the presence or absence of personal atopic comorbidities. Responses were evaluated using scales measuring the severity of atopic dermatitis, including EASI, quality of life scales (DLQI/IDLQI/CDLQI), POEM, and EVA Pruritus (over the last week). No significant differences were observed between patients with and without personal atopic comorbidities.

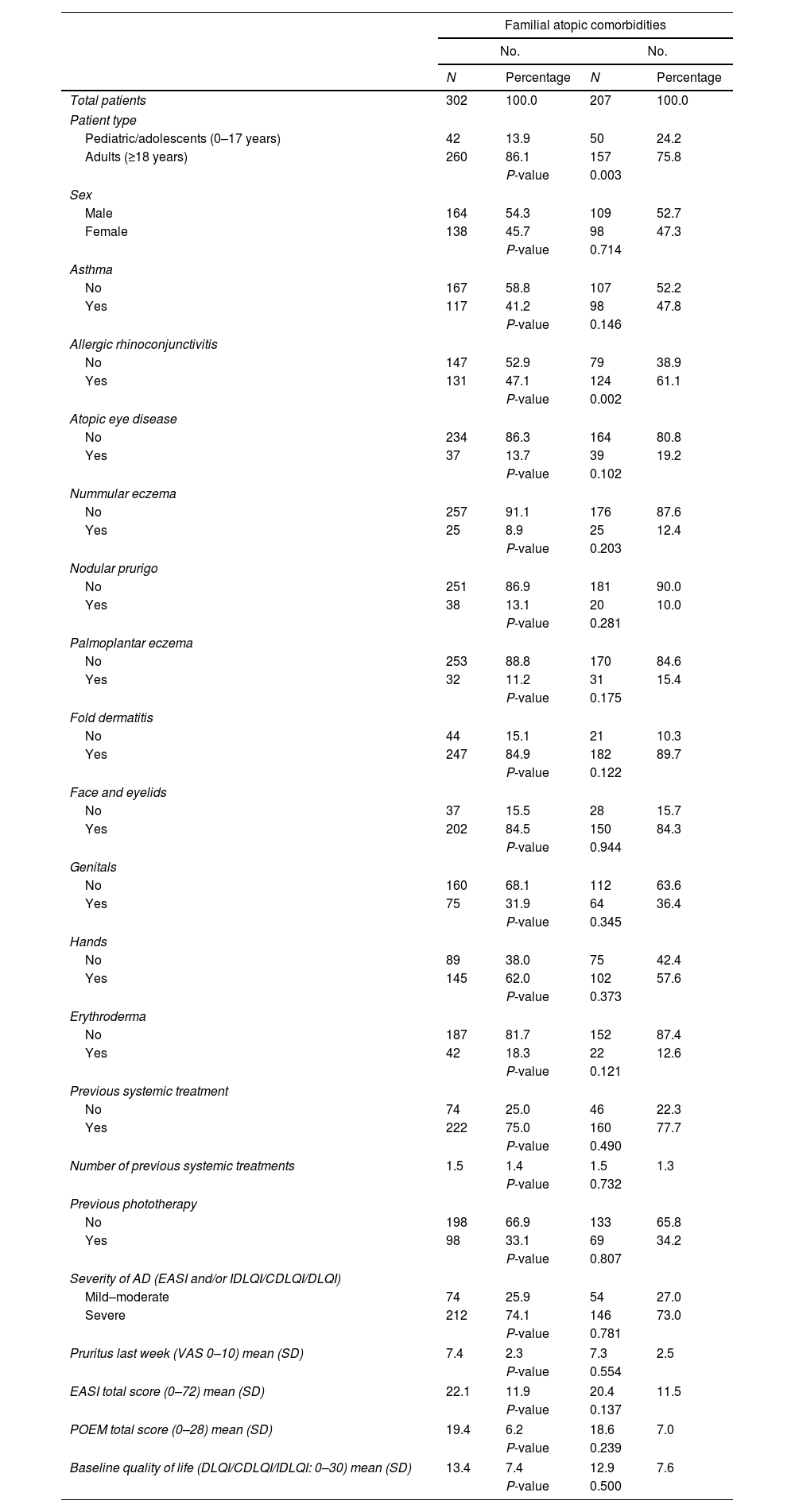

Among patients with familial atopic comorbidities, there was a higher proportion of pediatric/adolescent patients (24.2% vs. 13.9%; P=0.003) and a higher frequency of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis history (61.1% vs. 47.1%; P=0.002) vs. those without familial atopic comorbidities (Table 4).

Comparison of clinical characteristics of patients based on the presence or absence of familial atopic comorbidities.

| Familial atopic comorbidities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | No. | |||

| N | Percentage | N | Percentage | |

| Total patients | 302 | 100.0 | 207 | 100.0 |

| Patient type | ||||

| Pediatric/adolescents (0–17 years) | 42 | 13.9 | 50 | 24.2 |

| Adults (≥18 years) | 260 | 86.1 | 157 | 75.8 |

| P-value | 0.003 | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 164 | 54.3 | 109 | 52.7 |

| Female | 138 | 45.7 | 98 | 47.3 |

| P-value | 0.714 | |||

| Asthma | ||||

| No | 167 | 58.8 | 107 | 52.2 |

| Yes | 117 | 41.2 | 98 | 47.8 |

| P-value | 0.146 | |||

| Allergic rhinoconjunctivitis | ||||

| No | 147 | 52.9 | 79 | 38.9 |

| Yes | 131 | 47.1 | 124 | 61.1 |

| P-value | 0.002 | |||

| Atopic eye disease | ||||

| No | 234 | 86.3 | 164 | 80.8 |

| Yes | 37 | 13.7 | 39 | 19.2 |

| P-value | 0.102 | |||

| Nummular eczema | ||||

| No | 257 | 91.1 | 176 | 87.6 |

| Yes | 25 | 8.9 | 25 | 12.4 |

| P-value | 0.203 | |||

| Nodular prurigo | ||||

| No | 251 | 86.9 | 181 | 90.0 |

| Yes | 38 | 13.1 | 20 | 10.0 |

| P-value | 0.281 | |||

| Palmoplantar eczema | ||||

| No | 253 | 88.8 | 170 | 84.6 |

| Yes | 32 | 11.2 | 31 | 15.4 |

| P-value | 0.175 | |||

| Fold dermatitis | ||||

| No | 44 | 15.1 | 21 | 10.3 |

| Yes | 247 | 84.9 | 182 | 89.7 |

| P-value | 0.122 | |||

| Face and eyelids | ||||

| No | 37 | 15.5 | 28 | 15.7 |

| Yes | 202 | 84.5 | 150 | 84.3 |

| P-value | 0.944 | |||

| Genitals | ||||

| No | 160 | 68.1 | 112 | 63.6 |

| Yes | 75 | 31.9 | 64 | 36.4 |

| P-value | 0.345 | |||

| Hands | ||||

| No | 89 | 38.0 | 75 | 42.4 |

| Yes | 145 | 62.0 | 102 | 57.6 |

| P-value | 0.373 | |||

| Erythroderma | ||||

| No | 187 | 81.7 | 152 | 87.4 |

| Yes | 42 | 18.3 | 22 | 12.6 |

| P-value | 0.121 | |||

| Previous systemic treatment | ||||

| No | 74 | 25.0 | 46 | 22.3 |

| Yes | 222 | 75.0 | 160 | 77.7 |

| P-value | 0.490 | |||

| Number of previous systemic treatments | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.3 |

| P-value | 0.732 | |||

| Previous phototherapy | ||||

| No | 198 | 66.9 | 133 | 65.8 |

| Yes | 98 | 33.1 | 69 | 34.2 |

| P-value | 0.807 | |||

| Severity of AD (EASI and/or IDLQI/CDLQI/DLQI) | ||||

| Mild–moderate | 74 | 25.9 | 54 | 27.0 |

| Severe | 212 | 74.1 | 146 | 73.0 |

| P-value | 0.781 | |||

| Pruritus last week (VAS 0–10) mean (SD) | 7.4 | 2.3 | 7.3 | 2.5 |

| P-value | 0.554 | |||

| EASI total score (0–72) mean (SD) | 22.1 | 11.9 | 20.4 | 11.5 |

| P-value | 0.137 | |||

| POEM total score (0–28) mean (SD) | 19.4 | 6.2 | 18.6 | 7.0 |

| P-value | 0.239 | |||

| Baseline quality of life (DLQI/CDLQI/IDLQI: 0–30) mean (SD) | 13.4 | 7.4 | 12.9 | 7.6 |

| P-value | 0.500 | |||

CDLQI: Children's Dermatology Life Quality Index; DA: atopic dermatitis; SD: standard deviation; DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index; EASI: Eczema Area Severity Index; VAS: Visual Analog Scale; IDLQI: Infant's Dermatology Life Quality Index; POEM: Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure.

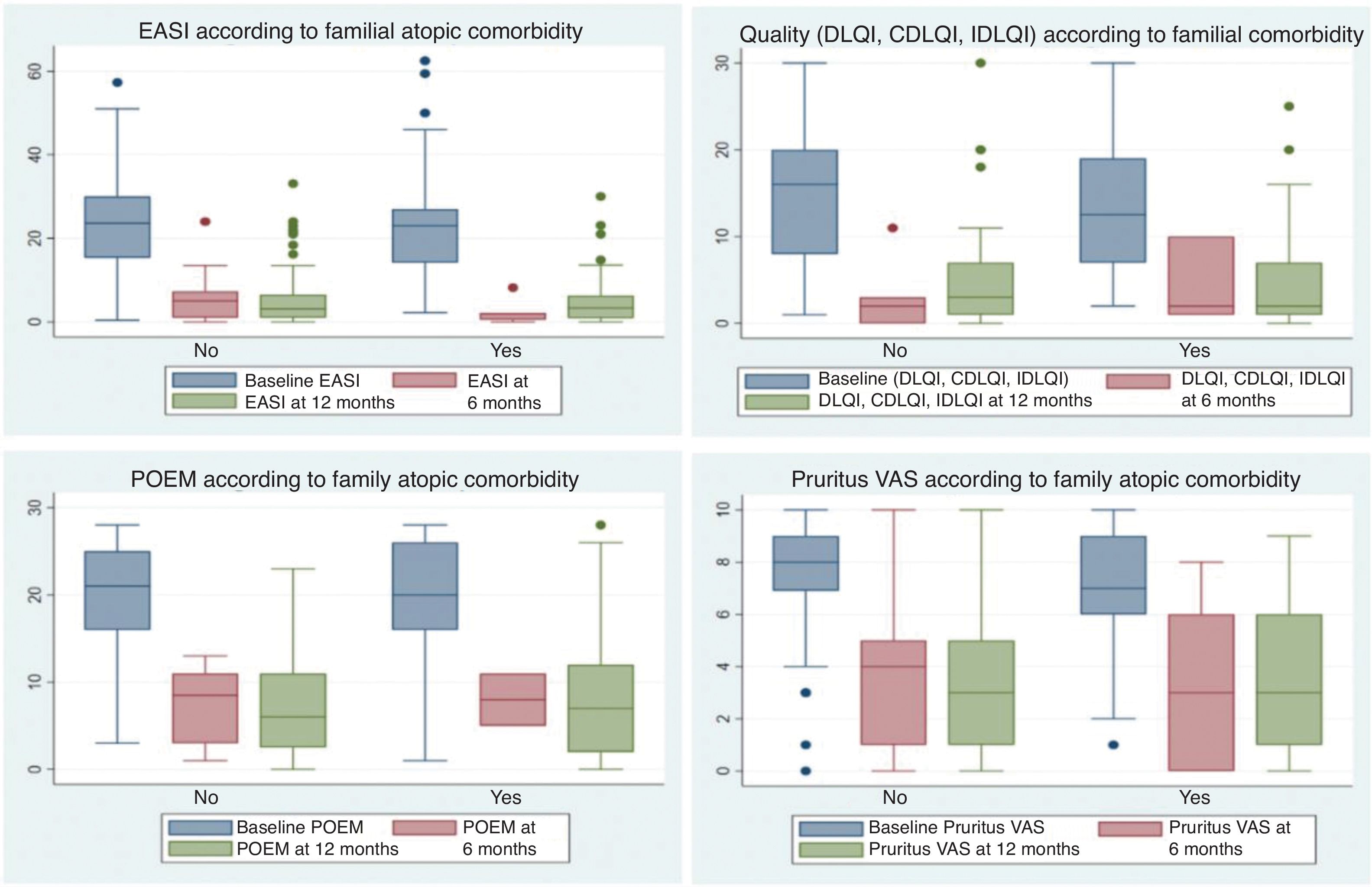

No differences were found between the two groups for other evaluated variables or in response to systemic therapies at the 6- and 12-month follow-up (Fig. 2).

Box plots showing response to systemic treatments at 6 and 12 months, based on the presence or absence of familial atopic comorbidities. Responses were evaluated using scales measuring the severity of atopic dermatitis, including EASI, quality of life scales (DLQI/IDLQI/CDLQI), POEM, and EVA Pruritus (over the last week). No significant differences were observed between patients with and without familial atopic comorbidities.

In our study on AD and atopic comorbidities, we observed similarities in most clinical characteristics between patients with and without these past medical histories. However, those with atopic comorbidities more frequently exhibited flexural dermatitis, an earlier onset of AD, a higher prior use of systemic therapies, and higher baseline POEM scores. These findings suggest a clinical profile characterized by early onset and extensive therapeutic trajectories, potentially increasing the likelihood of systemic therapy-related side effects. The greatest POEM impact could reflect greater perceived disease burden by the patient despite similar clinical characteristics and severity vs. those without atopic comorbidities. The cumulative physical, psychological, and inflammatory burden of the skin disease may play a significant role in shaping the patient's expectations and perspectives over their lifetime, a phenomenon described as cumulative life course impairment (CLCI).15 Of note, most literature supports the idea that atopic comorbidities are associated with greater disease perception and quality of life impacts.16 However, registries such as the Italian AtopyReg cohort17 made totally different findings, possibly due to a lower prevalence of atopic comorbidities in late-onset AD patients who tend to score higher on evaluation scales.

For patients with familial atopy histories, our study reveals a higher proportion of pediatric/adolescent patients, indicating, similar to personal atopic comorbidities, a greater likelihood of early onset and a long course of the disease. Furthermore, these patients more frequently had allergic rhinoconjunctivitis histories, which is consistent with previous studies highlighting the association between allergic rhinitis and early-onset AD.18 Nationwide, the EpiChron cohort also demonstrated that there was a significant association between allergic rhinitis and/or asthma in patients with AD, in the age group between 3 and 10 years.19

Atopic comorbidity histories may function as markers associated with early and prolonged disease, underscoring the need for individualized management to minimize disease impact. Studies suggest that adults with both AD and asthma exhibit different health care utilization patterns, including higher risks of hospital admission and unscheduled visits vs. those with AD or asthma alone.20 These data suggest that a comprehensive approach to managing AD and its comorbidities could help reduce health care costs.

The impact of these comorbidities on disease progression with treatments used in real-world clinical practice, particularly innovative therapies, remains of interest. Of the available treatments, only dupilumab has indications for atopic comorbidities such as asthma, nasal polyposis, or eosinophilic esophagitis. For other drugs, data is scarce, and the presence of comorbidities may have even limited recruitment in clinical trials.21 Therefore, some authors recommend selecting dupilumab for patients with comorbidities.22 In our study, however, no significant differences were observed in treatment choices or responses (at 6 and 12 months) based on the presence or absence of atopic comorbidities. Although short-term differences were not observed, potential long-term effects or specific factors influencing treatment responses warrant further analysis in future studies.

This study limitations include those inherent to observational studies, where confounding variables are difficult to control. While multicenter in its design, patients were recruited from specialized centers, likely making them more inclined to participate in research, which could limit generalizability. Regarding treatments, it is essential to consider that drugs such as dupilumab were available years before other therapeutic options, potentially influencing patient numbers and prescription patterns beyond the drug inherent characteristics. Additionally, follow-ups were short, with most patients being included in the past year. Information on the activity and severity of atopic comorbidities, which could significantly influence decision-making, is also unavailable. In fact, it seems plausible, based on the data presented, that the activity of atopic comorbidity – and its need for treatment – is the criterion that can impact the most the choice of treatment, rather than patient's history per se. Among the strengths, we highlight the sample size obtained through the prospective collection of data, rigorously conducted via the BIOBADATOP registry. Similarly, data collection was performed nationwide, obtaining a diverse and extensive sample from the various participant centers, which reinforces the representativeness of the findings and improves the external validity of the study.

In conclusion, personal or familial comorbidity histories may be associated with earlier onset and a more persistent course of the disease, a significant factor in real-world clinical decision-making. Long-term follow-up will be required to better understand disease progression and responses to new systemic therapies in these patient subgroups.

FundingThis study is part of the publications of the BIOBADATOP registry, a project promoted by the Fundación Piel Sana of the AEDV, which receives financial support from pharmaceutical companies, such as Sanofi, AbbVie, Pfizer, and Almirall. It was conducted independently in terms of the study planning and execution. Collaborating pharmaceutical companies did not participate in the design, collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of data, nor in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. The decision to submit the manuscript for publication was also made autonomously, without intervention from the collaborating pharmaceutical companies.

Conflicts of interestM. Munera-Campos has participated as an investigator in clinical trials sponsored by Sanofi, Abbvie, Lilly, Leo-Pharma, Pfizer, Almirall, Galderma, and Novartis, and received fees as a speaker and consultant from Sanofi, Lilly, Leo Pharma, Abbvie, and Galderma. P. Chicharro has participated in consultancies, symposiums, and clinical trials organized by Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Almirall, Sanofi Genzyme, Lilly, Abbvie, Novartis, Leo-Pharma, and Pfizer-Wyeth. A. González Quesada has worked as a consultant, speaker, and participated in clinical trials for Abbvie, Pfizer, Novartis, Sanofi, Boehringer, Bristol-Meyer, and Leo-Pharma. Á. Flórez Menéndez has acted as a speaker, consultant, and/or conducted clinical trials and research projects for Abbvie, ACELYRIN Inc, Alcedis GmbH, Almirall, Amgen, BMS, Celgene, Galderma, Incyte Corporation, Janssen-Cilag, Kyowa Kirin, Leo Pharma, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche Farma, Sanofi-Aventis, Sun Pharma, Takeda, and UCB Biosciences GmbH. P. de la Cueva Dobao has acted as an advisor, investigator, and/or speaker for Abbvie, Almirall, BMS, Boehringer, Celgene, Janssen, LEO Pharma, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, and UCB. AM. Giménez Arnau is or has recently been a speaker and/or advisor and/or received research funding from Almirall, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Avene, Celldex, Escient Pharmaceuticals, Genentech, GSK, Instituto Carlos III-FEDER, Leo Pharma, Menarini, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Novartis, Sanofi–Regeneron, Servier, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Uriach Pharma, and Noucor. Y. Gilaberte Calzada has served as an advisor for Isdin and Roche Posay, Galderma, in conferences for Almirall, Sanofi, Avene, Rilastil, Lilly, Uriage, Novartis, and Cantabria Labs, and has participated in research projects for Almirall, Sanofi, Pfizer, AbbVie, and LEO Pharma. M. Rodríguez Serna has served as an advisor for Sanofi, Pfizer, Leo, Novartis, and Abbvie. M. Elosua-González has participated as an investigator and/or speaker for AbbVie, Lilly, Galderma, LEO Pharma, Pfizer, UCB Pharma, and Sanofi Genzyme. J.F. Silvestre Salvador has collaborated as a speaker, advisor, and/or investigator for AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Incyte, Leo Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi Genzyme. M. Elosua-González has received fees or collaboration for training activities, lectures, and/or as an advisor for Abbvie, Lilly, Galderma, Novartis, GSK, LEO Pharma, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre Ibérica, UCB Pharma, and Sanofi Genzyme. E. del Alcázar-Viladomiu has participated as a speaker and/or principal investigator and/or sub-investigator in clinical trials for Amgen, Almirall, Janssen, Lilly, LEO Pharma, Novartis, UCB, and AbbVie. A. Batalla has received fees or collaborated in training activities, consultancy, or been involved in clinical trials for Abbvie, Celgene, Faes pharma, Isdin, Janssen, Leopharma, Lethipharma, Lilly, Mylan, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, and Sanofi. H. J. Suh Oh has collaborated as a speaker, advisor, and/or investigator for Abbvie, Almirall, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, Leo-Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche Farma, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, Takeda, and UCB Pharma. C. Couselo-Rodríguez has participated as a sub-investigator or speaker in projects sponsored by Abbvie, Sanofi, Leo-Pharma, Lilly, UCB, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, and Janssen. L. Curto-Barredo has received fees for lectures and/or as an advisor for Sanofi, Abbvie, Leo Pharma, Lilly, and Novartis. M. Bertolín-Colilla has received fees for lectures and/or as an advisor for Sanofi and Leo Pharma. R. Botella Estrada is or has been a member of the advisory board and/or speaker and/or participant in clinical trials for Pfizer, AbbVie, Almirall, Novartis, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Celgene, Roche, and SunPharma. I. Betlloch-Mas has served as an advisor on projects for Sanofi and Abbvie. G. Roustan Gullón has received fees for lectures and/or as an advisor for Sanofi, Abbvie, Leo Pharma, Lilly, and Novartis. A. Rosell-Díaz has received fees for lectures and/or as an advisor for Sanofi, Abbvie, Leo Pharma. M. Loro-Pérez has received fees/collaborations for training activities, lectures, and/or as an advisor for Abbvie, Johnson & Johnson, Galderma, Novartis, UCB Pharma, and Sanofi Genzyme. J.M. Carrascosa has participated as a principal/sub-investigator and/or received fees as a speaker and/or member of an advisory or steering committee for AbbVie, Novartis, Janssen, Lilly, Sandoz, Amgen, Almirall, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Biogen, and UCB. The remaining authors declared no conflicts of interest whatsoever.

We extend our gratitude to all the investigators involved in the BIOBADATOP registry for their additional efforts in daily clinical practice in data collection, as well as to the patients or their legal representatives for their willingness to participate in the registry. Their participation is essential for advancing knowledge in AD, contributing significantly to scientific progress in this field. This work was conducted as part of the Doctorate in Medicine program at Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona (M. Munera-Campos).