Hand eczema is a common condition associated with significantly impaired quality of life and high social and occupational costs. Managing hand eczema is particularly challenging for primary care and occupational health physicians as the condition has varying causes and both disease progression and response to treatment are difficult to predict. Early diagnosis and appropriate protective measures are essential to prevent progression to chronic eczema, which is much more difficult to treat. Appropriate referral to a specialist and opportune evaluation of the need for sick leave are crucial to the good management of these patients.

These guidelines cover the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of chronic hand eczema and highlight the role that primary care and occupational health physicians can play in the early management of this disease.

El eczema de manos es una patología frecuente con fuerte impacto en la calidad de vida de los pacientes y alto coste social y laboral. Su manejo por los médicos de atención primaria y de medicina del trabajo es complejo debido a la variedad de etiologías, la evolución difícilmente predecible de la enfermedad y la respuesta al tratamiento. El diagnóstico precoz y las medidas protectoras adecuadas son esenciales para evitar la cronificación, que es mucho más difícil de tratar. Una correcta derivación a un especialista y la valoración de una baja laboral en el momento adecuado resultan cruciales para un buen manejo de estos pacientes.

En esta guía sobre el eczema crónico de manos analizamos el proceso diagnóstico, las medidas preventivas y los tratamientos, con especial énfasis en el papel del médico de atención primaria y de medicina del trabajo en los estados iniciales de su manejo.

Hand eczema is a very common condition that affects an estimated 10% of the general population.1 It accounts for 80% of all occupational skin diseases and is a common cause of sick leave.2 In Spain, however, there are no national guidelines on how to prevent, diagnose, or treat this condition. The European guidelines for the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of chronic hand eczema were published in 2015,3 but they do not cover the complexity of care that characterizes the different levels of the Spanish public healthcare system. In Spain, general practitioners (GPs) provide the first point of contact for patients with hand eczema, but the lack of national guidelines means that there are no standardized criteria for clinical management and referrals. This complexity is further aggravated by the diversity of regional healthcare models.

Prompt diagnosis and treatment is necessary to prevent hand eczema from becoming chronic, but this requires coordination between the different levels of care. Systematized criteria thus are needed to determine how hand eczema patients should be treated in primary care, when they should be referred to a specialist, how they should be followed, and when they should be seen by an occupational health or health insurance physician. The Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV), through the Spanish Contact Dermatitis and Skin Allergy Research Group (GEIDAC), decided to draw up an updated review article to guide the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of hand eczema and offer unified, consensus-based criteria for referrals to secondary care.

This document was drawn up by members of the AEDV, which led the initiative, and representatives of the Spanish Society of Primary Care Physicians (SEMERGEN), the Spanish Society of Family and Community Physicians (semFYC), the Spanish Society of General and Family Practitioners (SEMG), and the Spanish Society of Occupational Medicine and Safety (SEMST).

MethodsThe document was prepared in several phases involving the review of existing evidence in various cycles of analysis and discussion. The process is described below:

- 1

Four members of the AEDV prepared a draft document containing the latest information on the definition, classification, diagnosis, and treatment of hand eczema. The literature search was performed in the US National Library of Medicine MEDLINE database and spanned articles published between 2008 and 2018. The results were filtered by relevance to the objectives of this guideline, although the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) checklist was not used The search was conducted using combinations of keywords (hand dermatitis, hand eczema, palmar dermatitis) that systematically covered all possible related uses. The qualifier terms were epidemiology, prevention, etiology, classification, pathophysiology, and treatment. Full searches were also made using specific drug terms, such as calcineurin inhibitors and alitretinoin. The draft document was also informed by existing guidelines, such as the European Society of Contact Dermatitis hand eczema guideline,3 the position paper of the European Cooperation in Science and Technology COST Action StandDerm (TD1206),2 the Canadian dermatitis management guidelines,4 and the Danish Contact Dermatitis guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of hand eczema.5

- 2

The draft was discussed in depth in May 2018 by members of the AEDV panel and the representatives of the participating societies (D.P.M. for SEMERGEN, R.S.S. for semFYC, R.S.C for SEMG, and A.A.G for SEMST) to ensure that all possible clinical perspectives were taken into account.

- 3

The discussions resulted in a definitive draft that was subsequently used to create an abbreviated set of recommendations for use by GPs and occupational health physicians in routine clinical practice. One of the main goals of this document was to standardize the criteria for referring patients with hand eczema to a specialist. It should be noted, however, that the document is not formally endorsed by the societies represented by the physicians involved in its development (SEMERGEN, semFYC, SEMG, and SEMST).

Hand eczema, or hand dermatitis, is a multifactorial disease with several etiologic and morphologic variants. It is essentially an inflammatory skin disease that affects the hands; it causes significant discomfort and can have a major impact on patient quality of life.

The clinical manifestations of hand eczema include erythema, edema, vesicles, crusting, scaling, lichenification, hyperkeratosis, and fissures. Hand eczema is considered acute when it predominantly consists of vesicles and crusting, and chronic when the main manifestation is hyperkeratosis. Early intervention is necessary as hand eczema can become chronic.6 The condition is classified as chronic when it lasts for at least 3 months or relapses at least twice a year despite adequate treatment and treatment adherence.3

EpidemiologyNumerous studies have described the prevalence of hand eczema in the general population and varying professions.1,7 A large literature review of studies published between 1964 and 2007 reported a point prevalence of around 4%, a 1-year prevalence of nearly 10%, and a lifetime prevalence of 15%.1 Similar rates have been described in a number of large, recent studies, many of which were conducted in Scandinavian countries. A large Norwegian epidemiological study involving over 50000 people, for example, reported prevalence rates of 11.3% for hand eczema in the general population and 4.8% for work-related hand eczema.8 A study of hand eczema in Swedish adolescents reported a 1-year prevalence of 5.2% and a lifetime prevalence of 9.7%; this incidence was similar to that observed in adults.9 Another Swedish study described a 1-year prevalence of 15.8% in adults and reported that women were twice as likely as men to be affected.10 In Denmark, the 1-year prevalence rate observed for hand eczema in adults aged 28 to 30 years was 14.3%.11

The severity of hand eczema has also been studied. An Italian study found that 83.5% of patients with hand eczema had chronic eczema, 21.3% had severe eczema, and 62.0% had eczema refractory to standard therapy.12 In the CARPE registry of German patients with chronic hand eczema, 23.4% of patients had very severe eczema, 47.0% had severe eczema, 20.1% had moderate eczema, and 9.6% had mild or very mild eczema.13 In the Swedish study of adolescents with hand eczema, 27.0% of patients had moderate to severe disease.9 Hand eczema tends to follow a relapsing, remitting course, and severity can change rapidly in individual patients.

Risk factorsThe risk factors for hand eczema are highly variable, particularly when allergens are involved. A number of general factors, however, have been consistently identified as increasing risk:

- •

Atopic dermatitis.1,10,11,14–20 A history of atopic dermatitis is the strongest predictor of chronic hand eczema in both children and adults. Atopic dermatitis is the most common cause of hand eczema in children.20 A study of chronic hand eczema in the general Danish population found an association between filaggrin mutations and chronic hand eczema in patients with atopic dermatitis.16

- •

Other atopic diseases, such as asthma and allergic rhinitis.14

- •

Tobacco smoking.21–25 While a recent meta-analysis did not demonstrate that smoking was a risk factor for hand eczema, the authors concluded that based on the data available, they could not confirm that smoking did not influence disease course.26 A recent study of patients with work-related hand eczema in Denmark found a strong association between smoking and disease severity.21 Although more studies are clearly needed, it is important to consider the inclusion of smoking cessation in treatment strategies for patients with hand eczema.23

- •

Dry skin.14

- •

Wet work and excessive hand washing.1,11,14,18,27–29 As hand eczema can affect a patient’s ability to work and may also be classified as an occupational disease, it has a significant social and economic impact. Workers most at risk are workers in the food processing industry and those frequently exposed to water, such as healthcare professionals and hairdressers.12 Healthcare workers have been identified as high-risk groups in Canada,30 Korea,18 the Netherlands,31 Denmark,19,28,32 Norway,8 and Germany,15 with prevalence rates ranging from 21.0% to 47.0%. In a Danish study, 53% of healthcare workers with hand eczema had positive patch test reactions, mostly to nickel, thiomersal, fragrances, rubber chemicals, and colophonium.32 A German epidemiological study found that 90.3% of German nurses with occupational skin diseases had hand eczema and 13.5% had concomitant methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) colonization, mainly in the nose (81.4%). Of these, 55.8% also had hand involvement.15 Chronic hand eczema is very common in odontologists in Japan (46.4%).14 In a recent study, hairdressers reported high rates of hand eczema compared with the general population, and many of them stated that they had left their job because of their condition.33 High prevalence rates have also been reported among hairdressers in Denmark,34,35 Turkey,36 and Croatia.37 The situation may vary significantly in other regions of the world. An Indian study, for example, found that most cases of occupational contact dermatitis occurred in farmers, construction workers, and housewives, and that 81.2% of patients with this diagnosis had hand eczema.38 The most common allergens identified were Parthenium hysterophorus in farmers, potassium dichromate in construction workers, and vegetables in housewives.

- •

Several studies have found hand eczema to be more common in women than men, but the exact reasons for this predominance are unknown.1,8,10,11,39,40

- •

Certain mutations in the filaggrin gene (see next section).

As hand eczema constitutes a group of highly heterogeneous conditions, no general pathological mechanisms have been established. It is, however, accepted that genetic factors (e.g., filaggrin mutations) and external factors (e.g., skin irritants) alter the structure and composition of the stratum corneum, disrupting the skin barrier and favoring the development of hand eczema. Filaggrin mutations have also been linked to the development of hand eczema, particularly in endogenous forms of the disease.41

Skin barrier disruption has a pathogenic role in chronic hand eczema and can lead to both irritant and allergic disease.42 One recent study showed that a number of important skin barrier proteins (filaggrin, hornerin, peptidases KLK5 and KLK7, and cystatin E/M) were downregulated in hand eczema.42 The skin barrier can be disrupted by both genetic and exogenous factors. Wet work is one of the main causes of skin irritation and can favor sensitization to antigens in hand eczema.43

The pathogenic role of skin microbiome in chronic hand eczema is attracting increasing attention. Patients with hand eczema have higher rates of S aureus colonization than healthy individuals, and patients with severe disease have a significantly higher density of S aureus than those with milder disease.44

Interleukins (ILs), such as IL-1 (IL-36α), may be involved in chronic hand eczema skin inflammation,45 and IL-36α may therefore become a useful biomarker for helping in the complex diagnosis of chronic hand ezcema.45

ClassificationProper classification of hand eczema is the first step towards effective and efficient treatment, 12 and it is also essential for stratifying patients in epidemiological and clinical studies. Several classification systems based on clinico-morphologic features and etiologic factors have been proposed. The relationship between these systems, however, is complex, as disease presentation and progression can vary from one type of hand eczema to the next. At this time, there is no universally accepted classification system.

The Danish Contact Dermatitis Group established 6 clinical (morphologic) types of hand eczema: recurrent vesicular hand eczema, chronic fissured hand eczema, hyperkeratotic palmar eczema, pulpitis, interdigital eczema, and nummular hand eczema.5,6,46,47

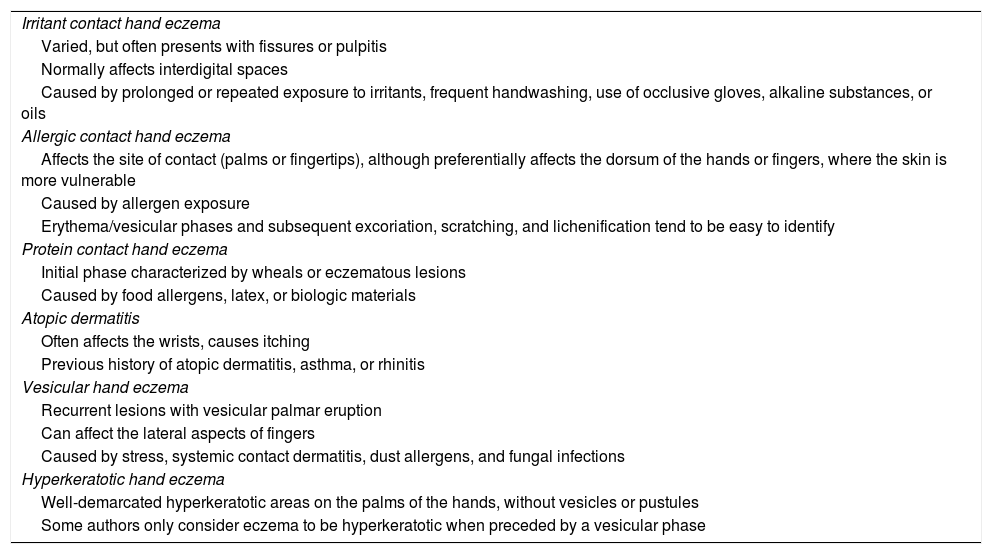

The most common types of hand eczema are shown in Table 1.3,6,48,49 The authors of a recent study were able to classify 89% of patients using the above diagnostic subgroups and in 7% of cases, two main diagnoses were required for classification.50 Nonetheless, several authors have estimated that at least 20% to 26% of all chronic hand eczema cases are idiopathic as they do not fit into any of these etiologic groups.5,49 Mixed forms of chronic hand eczema are common.6,50 A retrospective study of patients with occupational contact dermatitis in Denmark, for example, found that 6.4% of patients had a combined diagnosis of allergic and irritant contact dermatitis.51 Contact and atopic dermatitis may also coexist.52–54

Types of Hand Eczema.

| Irritant contact hand eczema |

| Varied, but often presents with fissures or pulpitis |

| Normally affects interdigital spaces |

| Caused by prolonged or repeated exposure to irritants, frequent handwashing, use of occlusive gloves, alkaline substances, or oils |

| Allergic contact hand eczema |

| Affects the site of contact (palms or fingertips), although preferentially affects the dorsum of the hands or fingers, where the skin is more vulnerable |

| Caused by allergen exposure |

| Erythema/vesicular phases and subsequent excoriation, scratching, and lichenification tend to be easy to identify |

| Protein contact hand eczema |

| Initial phase characterized by wheals or eczematous lesions |

| Caused by food allergens, latex, or biologic materials |

| Atopic dermatitis |

| Often affects the wrists, causes itching |

| Previous history of atopic dermatitis, asthma, or rhinitis |

| Vesicular hand eczema |

| Recurrent lesions with vesicular palmar eruption |

| Can affect the lateral aspects of fingers |

| Caused by stress, systemic contact dermatitis, dust allergens, and fungal infections |

| Hyperkeratotic hand eczema |

| Well-demarcated hyperkeratotic areas on the palms of the hands, without vesicles or pustules |

| Some authors only consider eczema to be hyperkeratotic when preceded by a vesicular phase |

Diagnosis of hand eczema is clinical and based on history taking and physical examination. Diagnostic tests (patch tests, prick tests, microbiological tests, and skin biopsy) are useful for ruling out other diseases and establishing an etiologic diagnosis.3,49

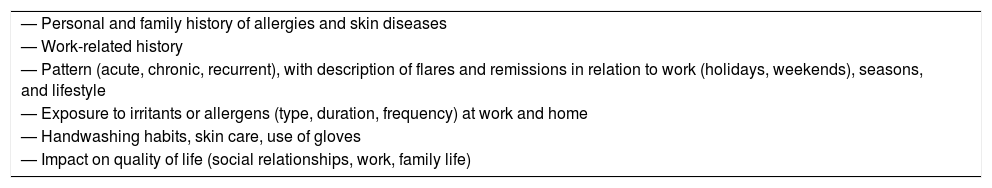

History taking is the first step in the diagnostic process. Both personal and work-related factors are important. The main factors that should be addressed during the patient interview are listed in Table 2. A note of the most significant findings from the interview should always be made in the patient’s medical record.

Factors to Investigate in a Patient With Possible Hand Eczema.

| — Personal and family history of allergies and skin diseases |

| — Work-related history |

| — Pattern (acute, chronic, recurrent), with description of flares and remissions in relation to work (holidays, weekends), seasons, and lifestyle |

| — Exposure to irritants or allergens (type, duration, frequency) at work and home |

| — Handwashing habits, skin care, use of gloves |

| — Impact on quality of life (social relationships, work, family life) |

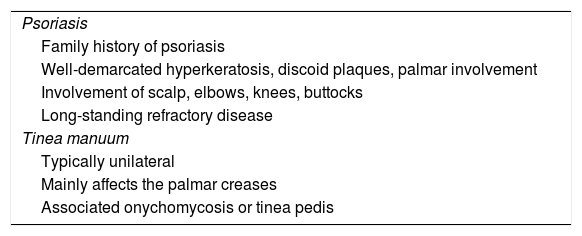

During the physical examination, the whole skin surface should be inspected, with attention paid to signs of dermatophytosis. Close inspection of the feet is important. Clinically, it may be difficult to differentiate between chronic hand eczema and other skin diseases that affect the hand, in particular psoriasis and mycosis.6,54 Some of the key aspects that should be considered in the differential diagnosis are shown in Table 3. Psoriasis is characterized by well-demarcated hyperkeratosis in discoid plaques, an absence of tingling and vesicles, and the presence of lesions on the scalp, nails, flexural areas of the elbows and knees, and buttocks. Patients with psoriasis also typically have a personal or family history of psoriasis or persistent seborrheic dermatitis. Fungal skin infections can be diagnosed by visual inspection or by potassium hydroxide testing or direct culture. Other conditions that can be confused with chronic hand eczema are lichen planus, mange, granuloma annulare, herpes simplex, erythema multiforme, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and dermatomyositis.6,54

Differential Diagnosis.

| Psoriasis |

| Family history of psoriasis |

| Well-demarcated hyperkeratosis, discoid plaques, palmar involvement |

| Involvement of scalp, elbows, knees, buttocks |

| Long-standing refractory disease |

| Tinea manuum |

| Typically unilateral |

| Mainly affects the palmar creases |

| Associated onychomycosis or tinea pedis |

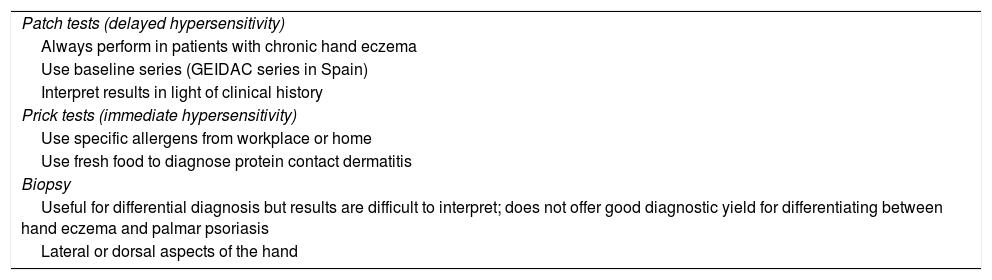

The clinical tools available for diagnosing chronic hand eczema are summarized in Table 4. Patch testing is the gold standard and must be performed in all types of chronic hand eczema, regardless of the morphology of the lesions or the tentative diagnosis. Patch tests should also be contemplated in patients with refractory or recurrent eczema, eczema with an atypical or varying distribution, and eczema with patterns suggestive of allergic contact disease.55 Patch and prick tests can rule out an allergic cause. Skin biopsy and fungal culture are normally only useful for ruling out other skin diseases. When making a diagnosis, it is important to recall that hand eczema can be triggered by a wide range of external and internal factors acting alone or in combination.

Clinical Tests Used to Diagnosis Chronic Hand Eczema.

| Patch tests (delayed hypersensitivity) |

| Always perform in patients with chronic hand eczema |

| Use baseline series (GEIDAC series in Spain) |

| Interpret results in light of clinical history |

| Prick tests (immediate hypersensitivity) |

| Use specific allergens from workplace or home |

| Use fresh food to diagnose protein contact dermatitis |

| Biopsy |

| Useful for differential diagnosis but results are difficult to interpret; does not offer good diagnostic yield for differentiating between hand eczema and palmar psoriasis |

| Lateral or dorsal aspects of the hand |

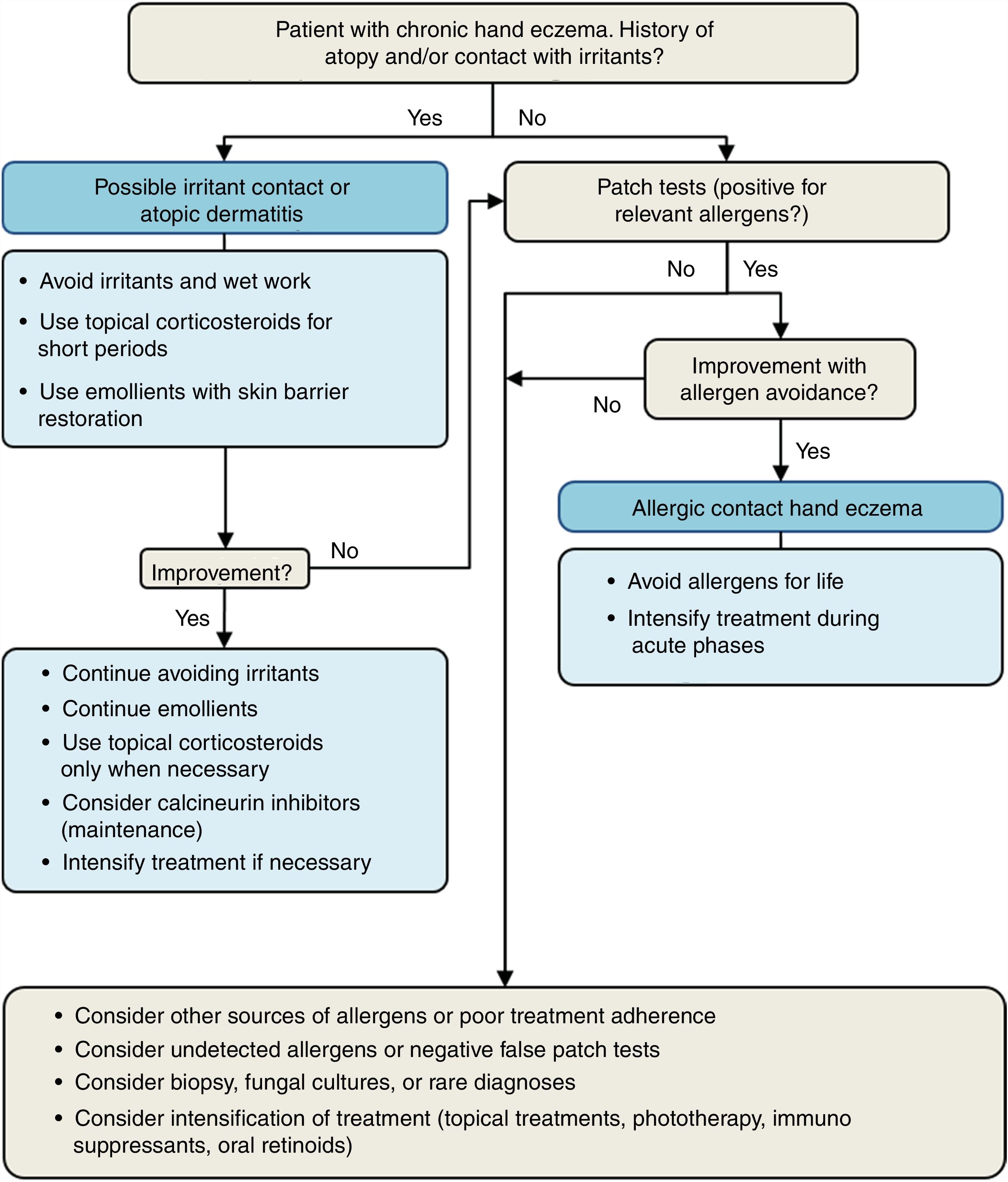

An algorithm to help identify the cause of chronic hand eczema is shown in Fig. 1. Patch tests are essential for diagnosing chronic allergic contact hand eczema.56 There are no useful diagnostic tools for detecting reactions to irritants in everyday clinical practice. Irritant contact hand eczema thus is often diagnosed on the basis of clinical patterns, testing of products handled by the patient, and patch test results (negative results are indicative of contact allergy). It should be noted, however, that contact and irritant hand eczema often coexist.51,56

Protein contact hand eczema should be clinically suspected in any patient who develops pruritus, wheals, or eczema immediately after handling material of biological origin (e.g., fruit, fish, animal intestines). In this case, the eczema is caused by prolonged contact with the proteins and is therefore diagnosed using prick tests rather than patch tests (which detect allergy to haptens). Prick-to-prick tests with suspect foods provided by the patient are often necessary. Although the agents responsible for classic allergic hand eczema are low-molecular–weight chemical agents, standard patch tests tend to be negative in contact hand eczema induced by proteins. Protein contact hand eczema is common in patients with dermal-epidermal barrier disruption due to atopy or previous exposure to irritants.

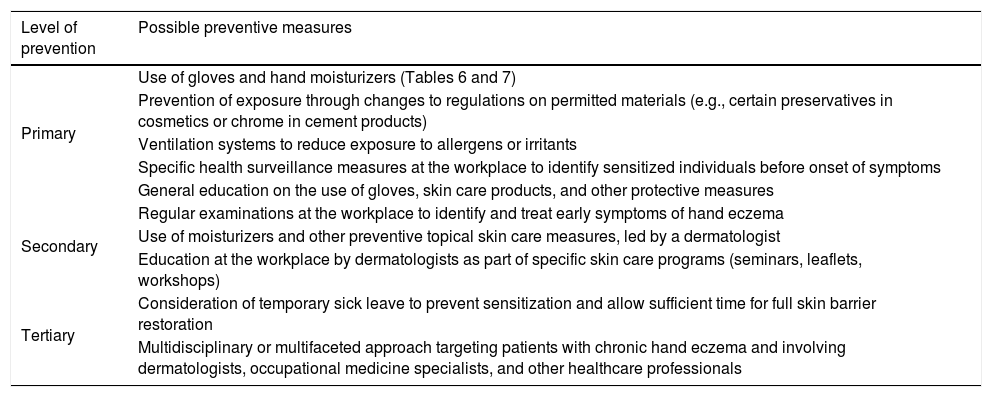

PreventionMeasures to mitigate or reduce the incidence of hand eczema can be classified as primary, secondary, or tertiary, depending on the stage of disease. Primary prevention measures aim to reduce the incidence of hand eczema in the healthy population. Secondary prevention measures, by contrast, are designed to prevent existing disease from becoming chronic, while tertiary prevention measures are designed to guide the clinical management of patients who have already developed chronic disease. The different measures, categorized by level of prevention, are summarized in Table 5.

Preventing Hand Eczema.

| Level of prevention | Possible preventive measures |

|---|---|

| Primary | Use of gloves and hand moisturizers (Tables 6 and 7) |

| Prevention of exposure through changes to regulations on permitted materials (e.g., certain preservatives in cosmetics or chrome in cement products) | |

| Ventilation systems to reduce exposure to allergens or irritants | |

| Specific health surveillance measures at the workplace to identify sensitized individuals before onset of symptoms | |

| General education on the use of gloves, skin care products, and other protective measures | |

| Secondary | Regular examinations at the workplace to identify and treat early symptoms of hand eczema |

| Use of moisturizers and other preventive topical skin care measures, led by a dermatologist | |

| Education at the workplace by dermatologists as part of specific skin care programs (seminars, leaflets, workshops) | |

| Tertiary | Consideration of temporary sick leave to prevent sensitization and allow sufficient time for full skin barrier restoration |

| Multidisciplinary or multifaceted approach targeting patients with chronic hand eczema and involving dermatologists, occupational medicine specialists, and other healthcare professionals |

Primary prevention is essential and should start at schools, with a particular focus on children with atopic disorders, who are more prone to developing hand eczema later in life. The goal of primary prevention is to prevent exposure to potential causative agents identified as risk factors in the general population.

Assessment of occupational risk involves identifying and quantifying risks at the workplace and is an essential component of primary prevention. Risks should then be classified and suitable preventive measures implemented using a multidisciplinary approach.2 The main types of primary prevention measures are 1) technical/organizational measures, 2) personal protection measures (hand hygiene and use of gloves and moisturizers), 3) education, and 4) access to specialist care.2

An example of an effective organizational measure is the introduction of regulatory measures to reduce or eliminate exposure to certain allergens, such as chromate in cement or glyceryl monothioglycolate in hairdressing products.57,58 Accelerator-free medical gloves may be an effective alternative for healthcare professionals allergic to rubber accelerators.59

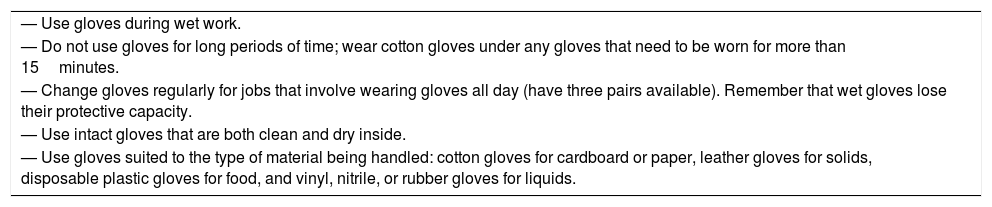

Protective gloves are the most important primary prevention measure (Table 6). Patients with hand eczema should always wear gloves over clean, dry hands when doing wet work or working with hazardous substances. Gloves should be worn as often as necessary but for the shortest time possible.2 Disposable gloves should never be used more than once and damaged gloves should be disposed of immediately. Cotton gloves should be worn for general housework that does not require contact with liquids (e.g., dusting) and under other gloves that need to be worn for longer than 15minutes.2 Latex gloves offer good protection against microorganisms and water-based products, but are relatively ineffective against oils, solvents, and chemical products. Nitrile gloves protect against oils and solvents, while vinyl gloves offer protection against most chemical products.49

General Measures: Gloves.

| — Use gloves during wet work. |

| — Do not use gloves for long periods of time; wear cotton gloves under any gloves that need to be worn for more than 15minutes. |

| — Change gloves regularly for jobs that involve wearing gloves all day (have three pairs available). Remember that wet gloves lose their protective capacity. |

| — Use intact gloves that are both clean and dry inside. |

| — Use gloves suited to the type of material being handled: cotton gloves for cardboard or paper, leather gloves for solids, disposable plastic gloves for food, and vinyl, nitrile, or rubber gloves for liquids. |

The authors of a Dutch study showed that a multifaceted hand eczema prevention strategy consisting of training (targeting special working groups), workplace reminders, and leaflets produced good overall results after a period of 6 months.60,61 The strategy, however, did not appear to be cost-effective.62

Secondary PreventionThe goal of secondary prevention is the early detection, diagnosis, and treatment of hand eczema by specialists. Patient education programs should aim to bring about behavioral changes at work or at home and encourage patients to use skin protection measures and eliminate exposure to allergens and irritants. It has been suggested that this information should be given in writing.49,63 Job counseling may also be an effective approach for encouraging secondary prevention in young adults at risk of hand eczema, as found by a German study of young adults with atopic dermatitis starting in high-risk occupations.64 Another German study demonstrated the long-term effectiveness of an interdisciplinary secondary prevention programme and stressed the importance of early detection and reporting of occupational hand eczema in the initial stages of disease.65

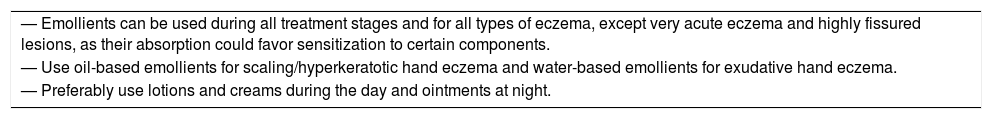

Protective creams and emollients are very important as they can prevent early disease from progressing (Table 7). Barrier creams provide a protective layer and should only be used on healthy skin, never on inflamed skin. They protect against common irritants such as water, detergents, metals, resins, oil-based materials, and UV light and they may also favor skin hygiene.49 It is important to note, however, that barrier creams may give a false sensation of security, leading to undue exposure to allergens or irritants. Under no circumstances should barrier creams replace physical measures such as gloves. A wide range of emollients can be recommended and used in clinical practice and it is widely accepted that these products can improve hydration, prevent itching, and help repair the skin barrier. Use of moisturizers can prolong disease-free periods in patients with successfully treated hand eczema.66 There is, however, limited evidence on the clinical effectiveness of specific formulations and as such no definitive recommendations can be made.3 Moisturizers should not be worn during working hours as they increase the risk of sensitization to allergens that can cause eczema. Instead, they should be used outside working hours to favor skin barrier restoration. More recent developments for the treatment of specific lesions include prescription emollient devices, which contain a complex mix of components designed to mimic the composition of the skin.67

General Measures: Emollients.

| — Emollients can be used during all treatment stages and for all types of eczema, except very acute eczema and highly fissured lesions, as their absorption could favor sensitization to certain components. |

| — Use oil-based emollients for scaling/hyperkeratotic hand eczema and water-based emollients for exudative hand eczema. |

| — Preferably use lotions and creams during the day and ointments at night. |

Tertiary prevention measures should be applied to patients who have already developed chronic hand eczema. The main goals in this case are to improve disease severity, reduce the use of corticosteroids, facilitate return to work, and improve quality of life. It may be advisable for patients with irritant contact hand eczema to temporarily stop work to prevent sensitization and favor full restoration of the skin barrier. A multidisciplinary approach involving dermatologists and occupational health specialists is recommended.3 The Osnabrück model has been proposed as an effective long-term strategy for patient rehabilitation.68,69 A recent study of the long-term effects of a tertiary individualized prevention program found that 96.9% of patients were able to return to work after participating in the program. In addition, 82.7% were still working after 3 years and 75.0% remained in the same profession.68

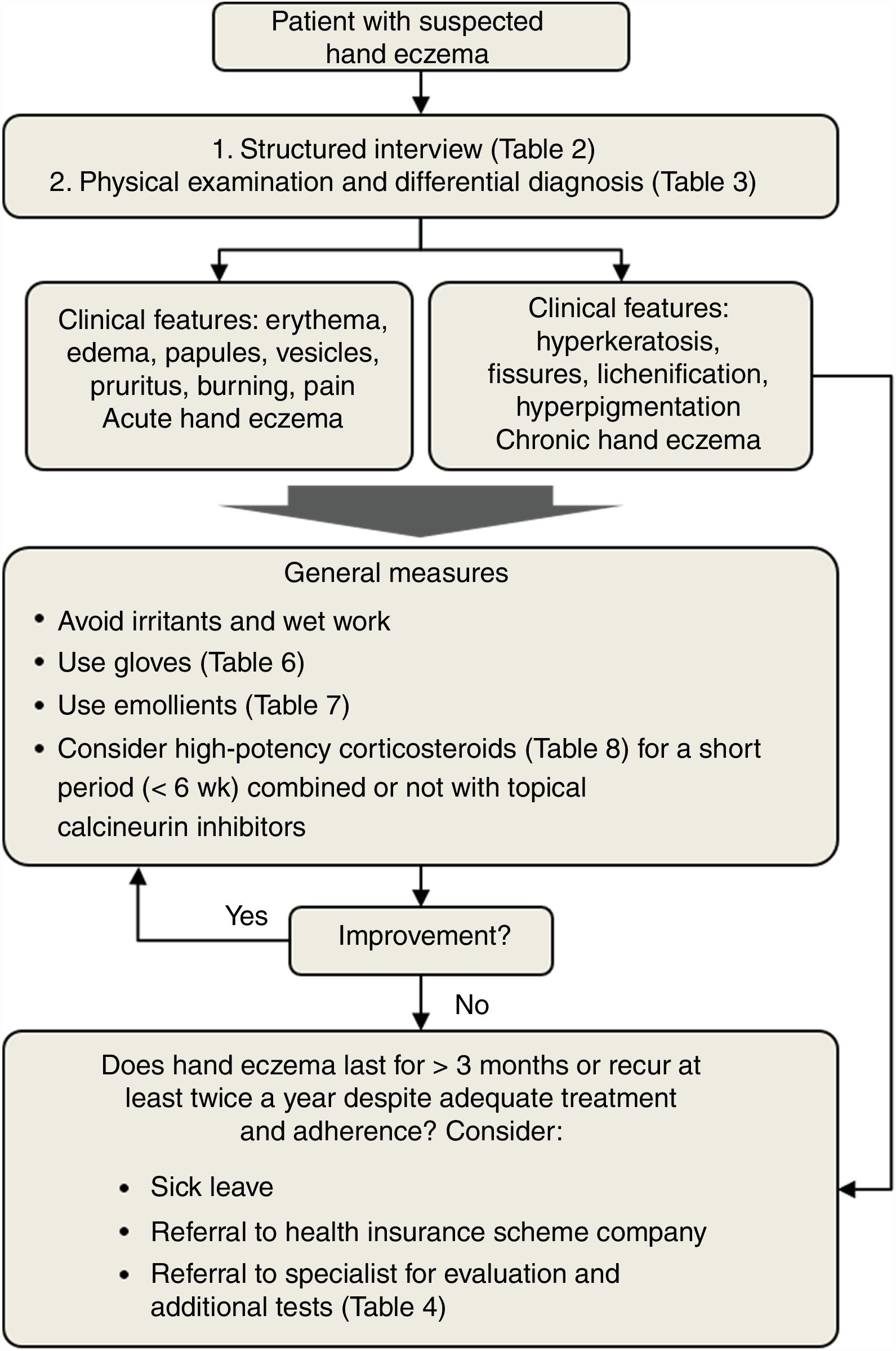

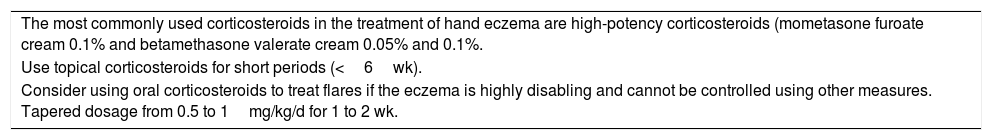

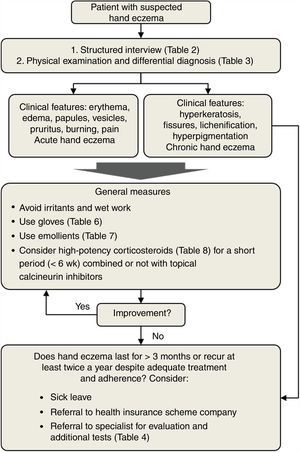

TreatmentTreatment of hand eczema should be individualized based on numerous factors, including age, clinical history, and profession. Treatment recommendations should be tailored to the cause of the hand eczema and the morphology and location of the lesions. Fig. 2 shows an algorithm for managing hand eczema in primary care. The first step is to conduct a structured patient interview and a full physical examination. This will guide the differential diagnosis and help decide on initial treatment. General measures include avoidance of irritants and wet work and use of gloves and emollients (Tables 6 and 7). If necessary, high-potency topical corticosteroids may be considered (Table 8). Patients with chronic hand eczema must always be referred to a dermatologist for additional tests and a definitive etiologic diagnosis. GPs should also consider granting the patient sick leave to enable full recovery.

Use of Corticosteroids.

| The most commonly used corticosteroids in the treatment of hand eczema are high-potency corticosteroids (mometasone furoate cream 0.1% and betamethasone valerate cream 0.05% and 0.1%. |

| Use topical corticosteroids for short periods (<6wk). |

| Consider using oral corticosteroids to treat flares if the eczema is highly disabling and cannot be controlled using other measures. Tapered dosage from 0.5 to 1mg/kg/d for 1 to 2 wk. |

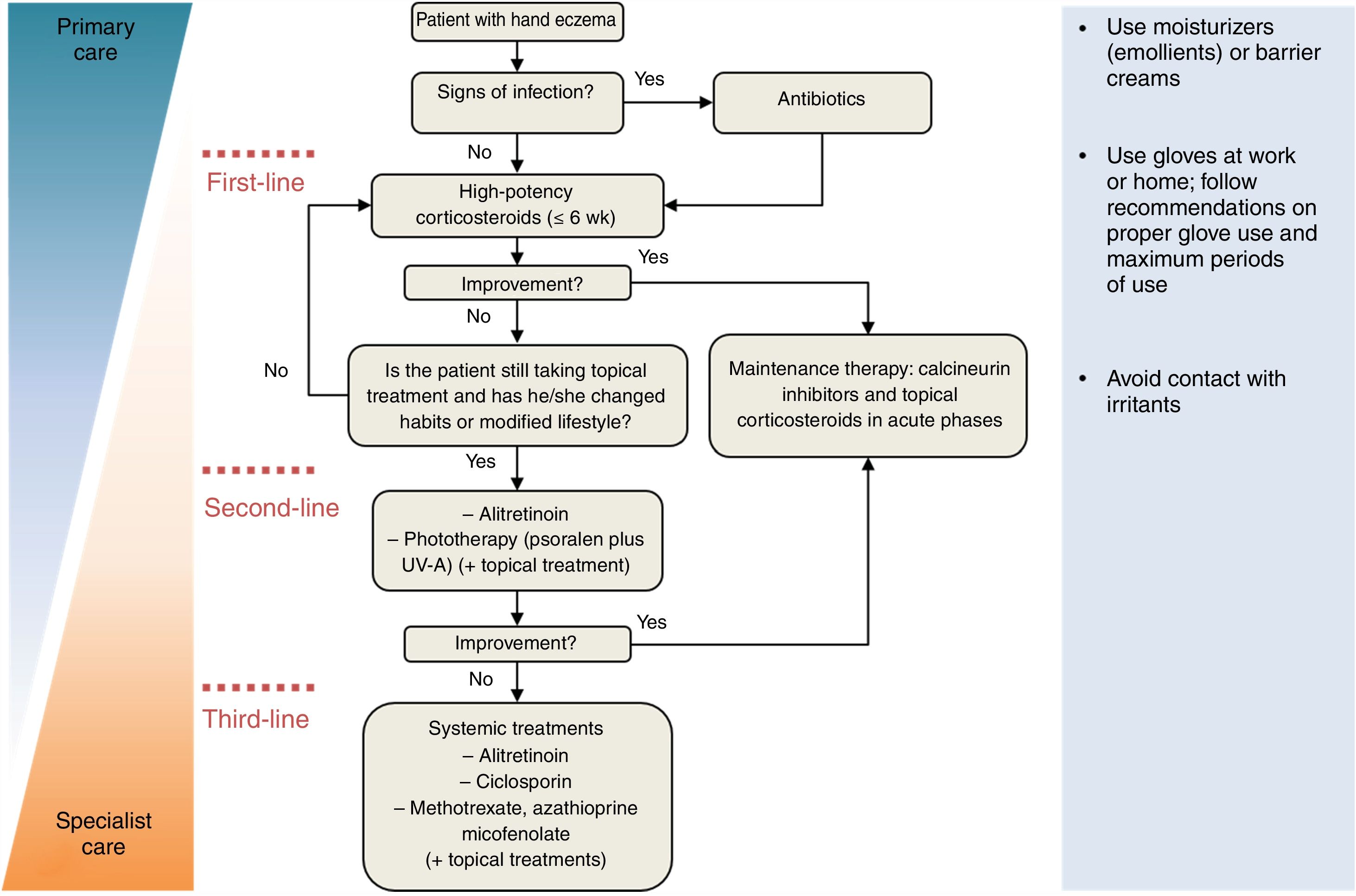

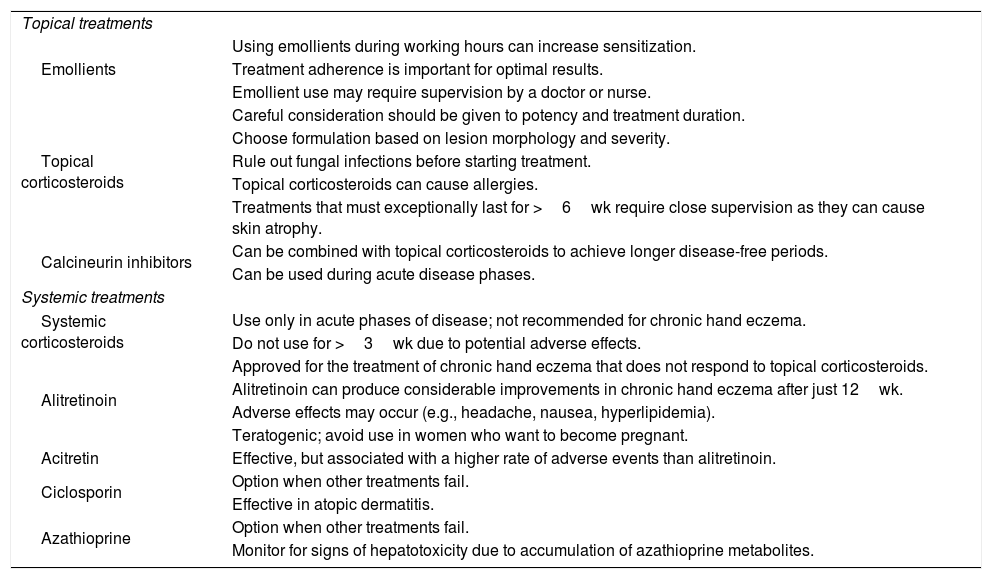

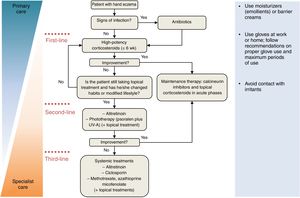

Table 9 summarizes the treatments available for hand eczema and Fig. 3 shows an algorithm for managing hand eczema in specialist care settings. Personalized follow-up is essential as long-term treatment effectiveness is often difficult to predict due to the lack of definitive randomized controlled trials evaluating and comparing the efficacy of different treatments. In many cases, it is also impossible to compare treatments across clinical studies because of variations in patient populations and a lack of standardized outcome measures.

Treatment Recommendations for Hand Eczema.

| Topical treatments | |

| Emollients | Using emollients during working hours can increase sensitization. |

| Treatment adherence is important for optimal results. | |

| Emollient use may require supervision by a doctor or nurse. | |

| Topical corticosteroids | Careful consideration should be given to potency and treatment duration. |

| Choose formulation based on lesion morphology and severity. | |

| Rule out fungal infections before starting treatment. | |

| Topical corticosteroids can cause allergies. | |

| Treatments that must exceptionally last for >6wk require close supervision as they can cause skin atrophy. | |

| Calcineurin inhibitors | Can be combined with topical corticosteroids to achieve longer disease-free periods. |

| Can be used during acute disease phases. | |

| Systemic treatments | |

| Systemic corticosteroids | Use only in acute phases of disease; not recommended for chronic hand eczema. |

| Do not use for >3wk due to potential adverse effects. | |

| Alitretinoin | Approved for the treatment of chronic hand eczema that does not respond to topical corticosteroids. |

| Alitretinoin can produce considerable improvements in chronic hand eczema after just 12wk. | |

| Adverse effects may occur (e.g., headache, nausea, hyperlipidemia). | |

| Teratogenic; avoid use in women who want to become pregnant. | |

| Acitretin | Effective, but associated with a higher rate of adverse events than alitretinoin. |

| Ciclosporin | Option when other treatments fail. |

| Effective in atopic dermatitis. | |

| Azathioprine | Option when other treatments fail. |

| Monitor for signs of hepatotoxicity due to accumulation of azathioprine metabolites. | |

Treatment algorithm for hand eczema. Education and lifestyle changes, such as the use of emollients and protective gloves and avoidance of irritants and allergens are obligatory throughout all treatment phases. Oral corticosteroids can be considered for flares. Adapted from De León et al.49.

It is highly recommendable that acute hand eczema be treated as early as possible to prevent it from becoming chronic, as chronic disease can be much more difficult to treat. As widely known, it is also essential to prevent re-exposure to irritants and allergens and to allow sufficient time for the skin barrier to regenerate. One of the main goals of any treatment strategy should therefore be to identify exogenous causes and recommend lifestyle changes and preventive measures.3

Topical TreatmentsMost cases of acute hand eczema can be adequately managed with a combination of preventive measures and topical treatments. These include corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus, pimecrolimus), iontophoresis, tar, and astringent and antiseptic solutions such as potassium permanganate and aluminium acetate.3

Topical CorticosteroidsTopical corticosteroids are the first-line treatment for hand eczema and can be highly effective in the short term (Table 5).3,49,63 Long-term use, however, can inhibit repair of the stratum corneum and cause skin atrophy (Table 8). Topical corticosteroids should only be used for longer than 6weeks in exceptional circumstances and always under medical supervision.3 The risk of immediate and delayed hypersensitivity reactions should also be considered. Any reactions should be investigated by patch testing.70 As a general rule, hand eczema should be treated with high-potency corticosteroids (betamethasone valerate cream 0.05% or 0.1% or mometasone furoate cream 0.1%) administered once a day. A clinical trial involving 44 patients with hand eczema showed that once-daily application of a potent corticosteroid cream (betamethasone valerate 0.1%) was superior to twice-daily application, especially in patients with moderate eczema.71 According to a recent study, approximately 50% of patients with chronic hand eczema do not respond to corticosteroids.39

Calcineurin InhibitorsTopical calcineurin inhibitors (tacrolimus ointment 0.1% in patients ≥16 years or 0.03% in patients <16 years; pimecrolimus cream 1%) can be used in patients who do not respond or are allergic to topical corticosteroids. One study comparing betamethasone and tacrolimus with an emollient showed that betamethasone and tacrolimus resulted in a higher ceramide/cholesterol ratio and a lower inflammatory response.72 It has been suggested that a combination of calcineurin inhibitors and corticosteroids could be a useful option for longer-term treatments.49

PhototherapyPhototherapy is a standard treatment option for chronic hand eczema refractory to corticosteroids, although the general opinion is that long-term treatment can increase the risk of skin cancer.3 The treatment of choice is PUVA (topical psoralen and UV-A light), although potential adverse effects include erythema and skin burns.

A recent study showed the potential benefits of using a 308nm excimer laser to treat chronic hand eczema; the treatment produced a 69% reduction in physician global assessment scores and a 70% reduction in lesion and symptom scores.73 One advantage of excimer laser therapy is that by targeting specific sites, it results in a lower cumulative dose of UV radiation than other UV treatments.73

Systemic TreatmentsAlitretinoinAlitretinoin (9-cis retinoic acid) has immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects and is authorized for use in the treatment of severe chronic hand eczema that does not respond to or responds inadequately to topical corticosteroids.3,49,74,75 It is therefore recommended as a second-line treatment in patients with chronic hand eczema refractory to topical corticosteroids.3

Several clinical trials and studies have provided strong evidence for the safety and efficacy of alitretinoin in the treatment of severe, refractory chronic hand eczema.76–78 In a large phase III trial involving patients with severe, refractory chronic hand eczema, 48% of patients responded well to oral alitretinoin compared with 17% for placebo at 24 weeks (P<.001).79 A second phase III study involving 596 patients with severe chronic hand eczema showed similar results, with a response rate of 40% for alitretinoin versus 15% for placebo.80

Another study analyzing the effectiveness of alitretinoin in patients with recurrent chronic hand eczema showed a response rate of 80% compared with 8% for placebo, suggesting that intermittent treatment with alitretinoin is suitable for the long-term management of chronic hand eczema.81 An observational study of 680 German adults with chronic hand eczema found that alitretinoin was effective in 56.7% of patients with different morphologic forms (hyperkeratotic-fissured, fingertip, and vesicular) and also showed that alitretinoin was both effective and well tolerated in routine clinical practice.82

Although the standard treatment duration for alitretinoin is 24 weeks, good tolerance has been observed up to 48 weeks.83 A small Korean study showed that alitretinoin administered for just 12weeks led to considerable improvement in 44.4% of patients with chronic hand eczema.84 Recent evidence from clinical practice in Spain also showed that alitretinoin is effective in the treatment of chronic hand eczema, and often produces satisfactory results after just 1 cycle.85

Although treatment with alitretinoin is well tolerated, dose-dependent adverse effects have been observed. These include headache (20% of patients on 30mg/d), mucocutaneous events, hyperlipidemia, and altered thyroid function.79,80 Based on data from postmarketing studies spanning 6 years, additional adverse effects include nausea, hypertriglyceridemia, increased creatinine phosphokinase, and depression.86 Long-term effects must also be considered as alitretinoin is teratogenic. As such, it should not be used during pregnancy or in the month preceding conception.

A recent study showed that treatment with alitretinoin normalized the expression of several skin barrier genes, such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin, claudin 1, loricrin, filaggrin and cytokeratin 10.87 These changes were correlated with general clinical effectiveness, suggesting that alitretinoin has a disease-modifying effect.87 It has been hypothesized that alitretinoin may benefit patients with dyshidrotic eczema by regulating aquaporin 3 and 10.88

Observational studies of German patients with severe chronic hand eczema have shown that alitretinoin produces rapid and significant improvements in quality of life and work productivity measured by physician global assessment scores and various quality-of-life markers.89,90 An Italian study of patients with chronic hand eczema also found that alitretinoin considerably improved patient quality of life.91

AcitretinA retrospective study of acitretin in the treatment of chronic hand eczema showed that while the drug was effective, it was associated with a higher incidence of adverse events than alitretinoin (43.1% vs. 29.5%).92 Nevertheless, the results of a recent study showed that low-dose acitretin induced clinical improvement in patients with various types of hand eczema.93 Patients with hyperkeratotic hand eczema have been found to be more responsive.92 A pilot study conducted in Canada showed that acitretin was effective in 33.3% of patients with severe chronic hand eczema.94 Acitretin, like alitretinoin, is a retinoid drug and as such has teratogenic potential. It should not be used in women who might want to become pregnant within 3 years of stopping treatment.

Systemic CorticosteroidsCurrent clinical practice guidelines suggest that systemic corticosteroids should not be used to treat severe chronic hand eczema for longer than 3 weeks. Long-term use is not recommended due to the risk of potentially dangerous adverse effects.3

CiclosporinCiclosporin has been used in patients with psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, and chronic hand eczema who have failed to respond to other treatments.3 The earliest studies of the use of ciclosporin in the treatment of hand eczema showed that oral ciclosporin was as effective as a topical corticosteroid (beta-methasone-17,21-dipropionate) and offered equivalent improvements in quality of life.95,96 The drug also exhibited good long-term effectiveness, even after short treatment periods.97 A recent retrospective study showed that 62.9% of patients responded well to ciclosporin after 3 months of treatment and that response was particularly good in patients with recurrent vesicular hand eczema. The median drug survival rate in patients with chronic hand eczema was 10.3 months. The main reasons for treatment interruption were adverse events, particularly at the start of treatment, and ineffectiveness.98 Patients on ciclosporin should be carefully monitored as there is a risk of serious adverse events such as nephrotoxicity and an increased risk of cancer, a rise in blood pressure, and infections.3

AzathioprineThere is limited evidence on the efficacy of azathioprine for the treatment of hand eczema, but it is an option for patients in whom other treatments have failed or been insufficient.3 In certain cases, measurement of circulating 6-thioguanine nucleotide TGN) and methylated 6-methylmercaptopurine levels at baseline and thereafter at regular intervals can help optimize dosage regimens, improve clinical effectiveness, and prevent adverse effects, as azathioprine metabolites can cause hepatotoxicity.99 Azathioprine has been approved for the treatment of Parthenium dermatitis in India, where this condition is very common.100

Other TreatmentsMethotrexate and mycophenolate can be used off-label as second- or third-line treatments for hand eczema, but their use in this setting is supported by a low level of evidence.49,101 In one study, methotrexate administered over 8 to 12 weeks proved effective, but subsequent loss of effectiveness and onset of adverse events led to its interruption.102 The drug also appears to be less effective than other systemic treatments such as acitretin.103 Methotrexate has been used successfully in children with nummular eczema.104 Oxybutynin, an alternative treatment for hyperhidrosis, has been found to improve coexistent dyshidrotic eczema.105

Hand Eczema: Key Concepts

- •

Hand eczema is a multifactorial disease that is very common in the general population.

- •

Early diagnosis and treatment is essential for preventing chronic disease.

- •

Chronic hand eczema is eczema that persists for at least 3 months or recurs at least twice a year despite adequate treatment and treatment adherence.

- •

There is no universally accepted classification of hand eczema, but diagnostic subgroups can be established based on morphologic and etiologic criteria.

- •

Hand eczema is diagnosed clinically based on history taking and physical examination. Patch tests, prick tests, microbiological tests, and skin biopsies are useful for ruling out other diseases or establishing an etiologic diagnosis.

- •

When faced with a case of hand eczema, GPs should recommend adequate protection against irritants and moisture and correct usage of gloves and emollients.

- •

GPs should assess the need for sick leave in patients with chronic hand eczema and refer the patient to a specialist for additional tests.

- •

As hand eczema is often work related, risk prevention is essential in certain occupations.

This document was funded by an unconditional grant from GlaxoSmithKline.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank Francisco López de Saro for his support in writing and revising this manuscript.

*Please cite this article as: Silvestre Salvador JF, et al. Guía para el diagnóstico, el tratamiento y la prevención del eccema de manos. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;111:26–40.