Infantile hemangiomas are the most common benign tumor in children. They have 3 phases of development: a proliferative phase, an involuting phase, and involution. Although active treatment is often not required, it is necessary in some cases. Of the possible treatments for hemangiomas, lasers have been shown to be effective in all phases of development. We report our experience with dual-wavelength sequential pulses from a pulsed dye laser and an Nd:YAG laser.

Material and methodsThis was a retrospective, descriptive study of patients with infantile hemangioma in different phases of development treated with pulsed dye laser pulses followed by Nd:YAG laser pulses. Four dermatologists assessed the effectiveness of treatment on a scale of 10 to 0. Adverse effects and incidents related to treatment were recorded. The median and interquartile range were calculated as descriptive statistics. Pretreatment and posttreatment comparisons were performed using the Wilcoxon test.

ResultsTwenty-two patients with hemangiomas in different phases of development were included. A statistically significant improvement was obtained both for the entire group and for different subgroups. Posttreatment events were reported in 4 patients, and included edema and ulceration, skin atrophy, and hyperpigmentation.

ConclusionsWe believe that treatment with dual-wavelength light from a pulsed dye laser and a Nd:YAG laser is a viable treatment option for infantile hemangiomas when first-line therapies are ineffective or contraindicated.

Los hemangiomas infantiles son los tumores benignos más frecuentes en la infancia, presentando una fase proliferativa, una fase de involución y una fase residual. En muchas ocasiones no precisan de un tratamiento activo. No obstante, en algunos pacientes se impone la necesidad de un tratamiento. Entre las posibilidades terapéuticas ha demostrado utilidad, durante todas las fases evolutivas de la lesión, el tratamiento con láser. Comunicamos nuestra experiencia con el láser dual secuencial de colorante pulsado (LCP) y Nd:YAG.

Material y métodosSe efectuó un estudio retrospectivo y descriptivo de los pacientes con hemangiomas infantiles en diversas fases evolutivas tratados con el láser dual de LCP y Nd:YAG. Cuatro dermatólogos valoraron el grado de efectividad en una escala del 10 al 0. Se recogieron los efectos adversos e incidencias relativas al tratamiento. En el análisis se utilizó para los valores descriptivos la mediana y el rango intercuartílico y la prueba de Wilcoxon para la comparación pre y postratamiento.

ResultadosSe recogieron 22 pacientes con hemangiomas en distintos estadios evolutivos, obteniéndose una mejoría estadísticamente significativa tanto en el conjunto de todos los pacientes como en los distintos subgrupos. Cuatro pacientes presentaron incidencias postratamiento: edema y ulceración, atrofia cutánea e hiperpigmentación.

ConclusionesConsideramos que el láser dual de LCP y Nd:YAG puede ser una alternativa para el tratamiento de hemangiomas infantiles cuando las terapias consideradas de primera línea se muestran ineficaces o están contraindicadas.

Infantile hemangiomas are the most common benign tumor in children, and their incidence is higher in girls and premature infants.1–3 The tumors usually present as a single sporadic lesion, although multiple and familial forms are not uncommon. Infantile hemangiomas are vascular tumors, which are not usually present at birth but appear during the first weeks of life and grow rapidly over the following months (proliferative phase). The tumor then stabilizes and, after the child's first birthday, begins a slow, gradual regression that can last throughout childhood (involuting phase).4,5 Although it is possible for infantile hemangiomas to regress completely, residual lesions of various types—atrophic scars, redundant fibrofatty tissue, yellowish discoloration, and telangiectasias—persist in a significant number of patients (involuted phase).

Fortunately, because of the benign course described above, most infantile hemangiomas (especially smaller ones and those located in non–cosmetically-sensitive areas) do not require treatment and can be managed by watchful waiting. The tumors should be monitored especially closely during the proliferative phase so that any complications that would necessitate active treatment—such as ulceration, pain, functional impairment, or the possibility of abnormal scarring and disfigurement—can be detected.

The treatment of infantile hemangiomas varies depending on the phase of development, site, and characteristics of the lesion and whether or not visceral involvement or comorbidities are present. Of the treatments currently available, oral propranolol is the first-line option because of its proven efficacy and good safety profile.6–9 Other systemic treatments such as corticosteroids, bleomycin,10 and interferon alfa are also used occasionally. Topical medications such as corticosteroids, β-blockers,11,12 platelet-derived growth factor, and imiquimod13 and various medical and surgical techniques such as sclerotherapy, cryotherapy, radiotherapy, electrocautery, and conventional surgery have also been shown to be useful. Laser treatment also plays an important role.

In this study, we present our experience with the treatment of hemangiomas in various phases of development using dual-wavelength sequential pulses from a pulsed dye laser (PDL) and a Nd:YAG laser (Cynergy Multiplex, Cynosure, Inc., Westford, MA, United States).

Materials and MethodsStudy PopulationThis was a retrospective, descriptive, nonrandomized study of patients with infantile hemangiomas in different phases of development who were treated with dual-wavelength pulses from a PDL and a Nd:YAG laser in the laser department of Hospital Ramón y Cajal in Madrid, Spain, between May 2006 and July 2011. Patients with an incomplete clinical history or insufficient photographic documentation before or after the treatment were excluded.

ProceduresWe informed the patients in detail of the likely benefits, risks, and potential complications of the treatment and about the other therapeutic alternatives available. Written informed consent was obtained for all patients before the treatment was started.

In 16 patients, a topical anesthetic cream containing lidocaine and prilocaine (Eutectic Mixture of Local Anesthetics [EMLA], AstraZeneca, Wedel, Germany) was applied under occlusion 2hours before the start of each session in order to reduce the pain associated with the laser treatment.

The parameters for the sequential dual-wavelength pulses from a 595nm PDL and a 1064nm Nd:YAG laser were as follows: with a 10mm spot size, a 10ms pulse with a PDL at a fluence of 6-10J/cm2, a 1 second delay, followed by a 15ms pulse with a Nd:YAG laser at a fluence of 30-75J/cm2; or, with a 7mm spot size, a 10ms pulse with a PDL at a fluence of 6-10J/cm2, a 1 second delay, followed by a 15ms pulse with a Nd:YAG laser at a fluence of 50-90J/cm2. The spot size was chosen on the basis of lesion size. Patients attended treatment sessions approximately once every 6 months (more frequently if they had proliferative lesions and less frequently if they had residual lesions).

A forced-air cooling device (Cryo 5, Zimmer MedizinSysteme GmbH, Neu-Ulm, Germany) set to its highest fan speed (6) was used throughout the treatment. In addition, ice was applied immediately after the treatment in patients with larger hemangiomas with a prominent deep component.

For posttreatment care, patients were instructed to apply a topical antibiotic cream (fusidic acid, Fucidine, LEO Pharma, Barcelona, Spain) once a day for approximately 1 week and, in order to prevent postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, to avoid exposure to sunlight and use sunscreen with a sun protection factor of 50 or higher for at least 2 months after each treatment session.

AssessmentWe used a visual scale based on photographs taken before the first treatment session and at least 2 months after the last session. Taking into account skin color and texture and lesion height, 4 dermatologists evaluated the effectiveness of the treatment on a scale of 10 to 0, where 10 was the original pretreatment lesion and 0 was completely normal skin. Each patient's improvement was calculated as the mean of those 4 scores.

We also searched patient photographs and medical histories for evidence of transient adverse effects such as edema, infection, and ulceration, as well as longer-term effects such as pigmentary changes and abnormal scarring.

In addition to studying the entire group of patients, we also studied various subgroups (patients with proliferative, involuting, and involuted lesions) independently.

Statistical AnalysisData were checked for normal distribution with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov goodness-of-fit test. Normal distribution was not found for the evaluators’ individual scores or the mean scores for any of the variables. Median and interquartile range (IQR) were therefore used as descriptive statistics.

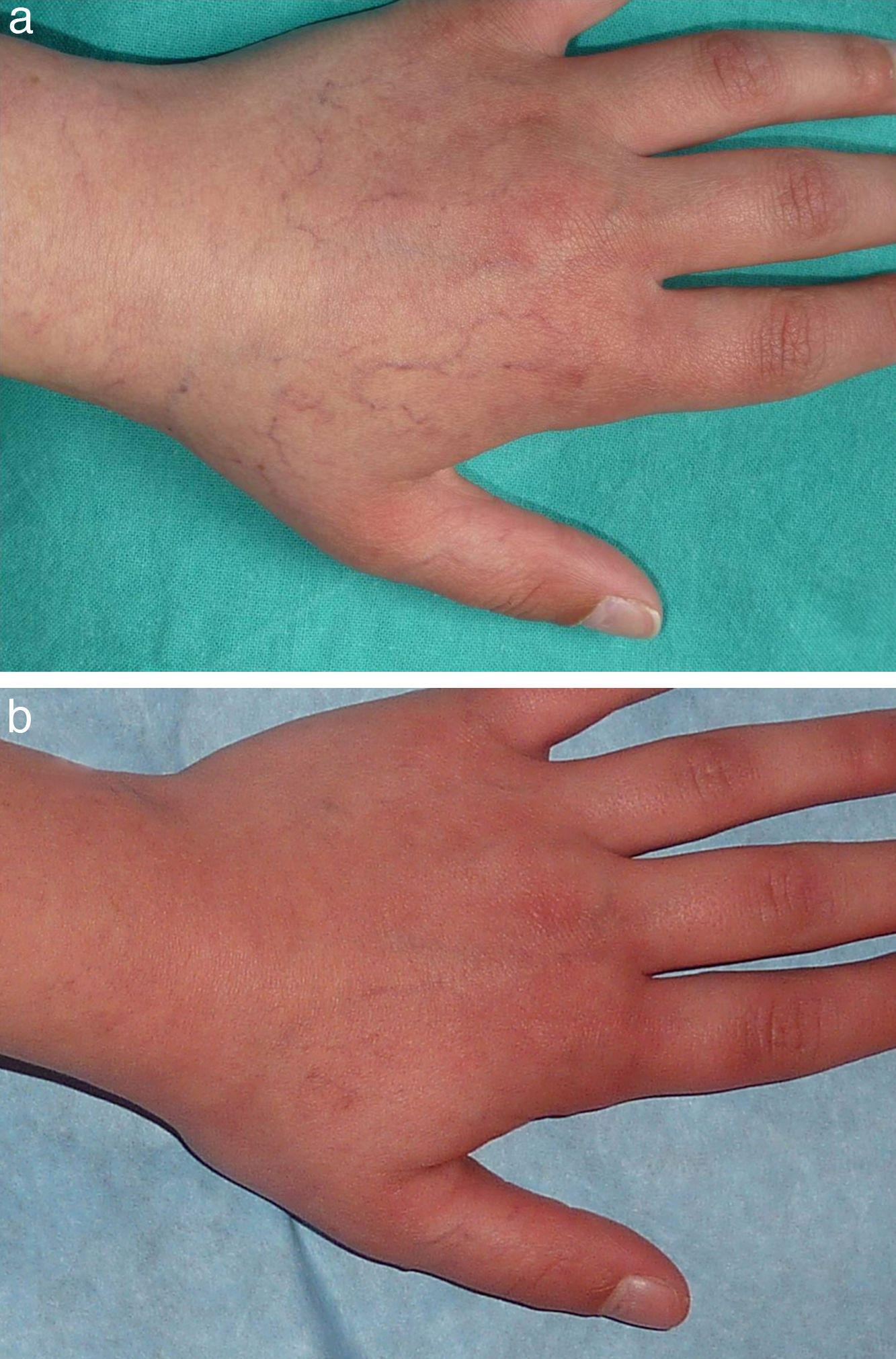

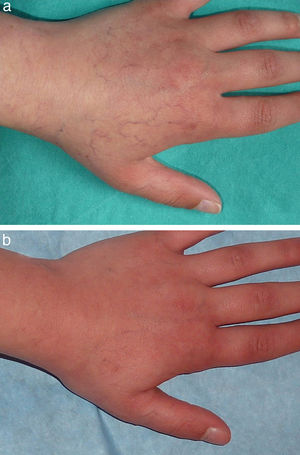

The Wilcoxon test was used to evaluate the difference between the initial and final values; statistical significance was set at P<.05.

Agreement between observers was assessed with the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).

ResultsTwenty-two patients (20 girls and 2 boys) with infantile hemangiomas, between the ages of 5 months and 13 years, were included in the study. At the time of treatment, the lesions were in different phases of development: proliferative in 2 patients, involuting in 9 patients, and involuted in 11 patients. Five patients had received no prior treatment; the others had received at least 1 of the following: propranolol (n=8), systemic corticosteroids (n=3), surgery (n=4), and PDL (n=9). None of the patients received concomitant treatment while undergoing PDL and Nd:YAG laser treatment. The data are presented by individual patient in Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics, Prior Treatments, and Number of PDL-Nd:YAG Laser Treatment Sessions for Each Patient.

| Patient No. | Sex | Age | Phase of Development | Site | Prior Treatments | No. of PDL-Nd:YAG Laser Treatment Sessions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 8 mo | Proliferative | Lower back | Propranolol, PDL | 2 |

| 2 | Male | 5 mo | Proliferative | Left cheek | None | 2 |

| 3 | Female | 2 y | Involuting | Nose | Propranolol | 3 |

| 4 | Female | 6 y | Involuting | Upper lip | PDL | 1 |

| 5 | Male | 15 mo | Involuting | Right mandibular area | None | 3 |

| 6 | Female | 2 y | Involuting | Right cheek | None | 2 |

| 7 | Female | 12 mo | Involuting | Nose | Propranolol | 5 |

| 8 | Female | 18 mo | Involuting | Right cheek | None | 1 |

| 9 | Female | 3 y | Involuting | Left cheek | Oral corticosteroids | 3 |

| 10 | Female | 17 mo | Involuting | Left cheek | Oral corticosteroids, propranolol | 1 |

| 11 | Female | 12 mo | Involuting | Upper lip | Oral corticosteroids, propranolol | 2 |

| 12 | Female | 10 y | Involuted | Left side of face | Surgery, PDL | 2 |

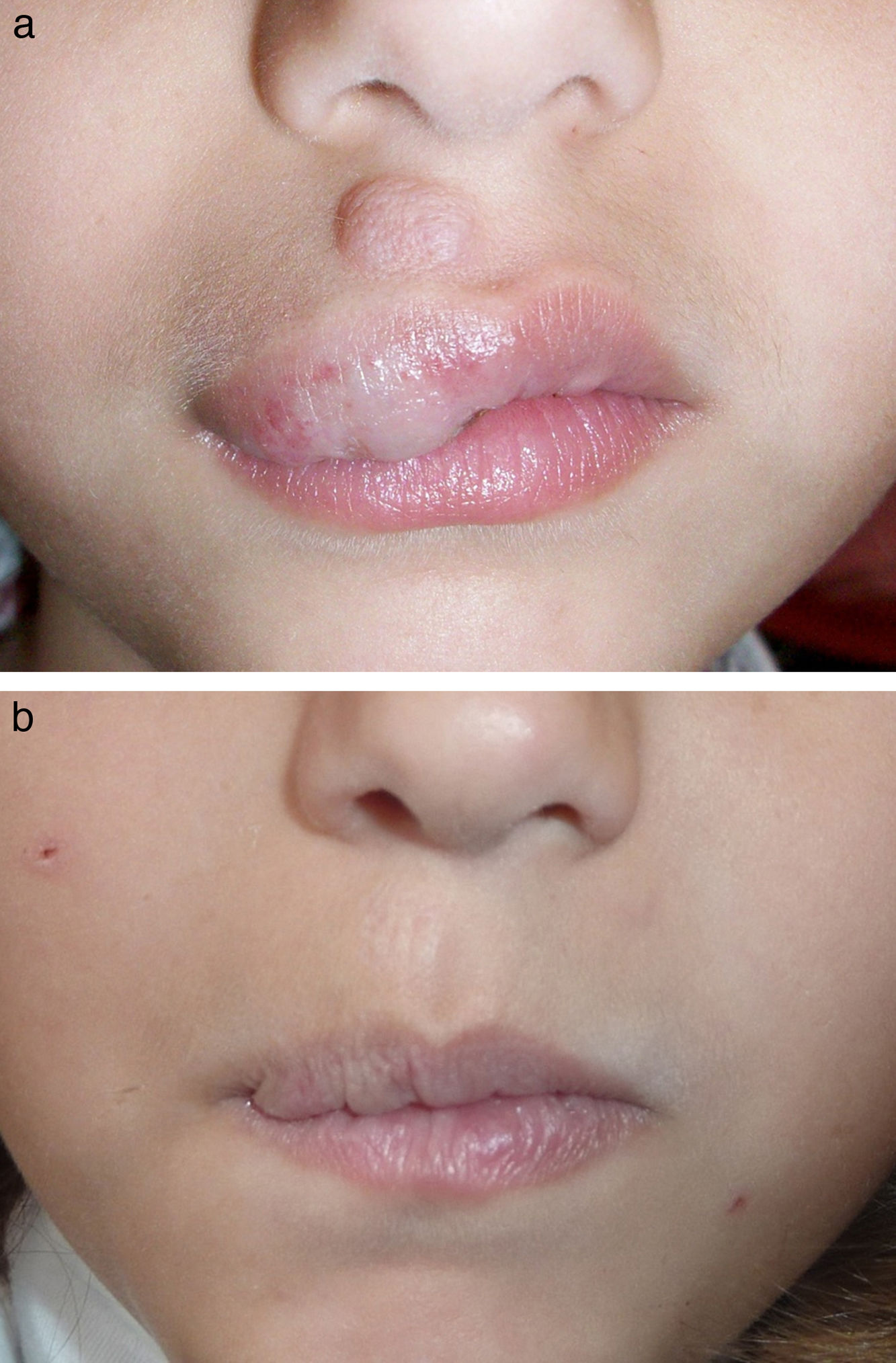

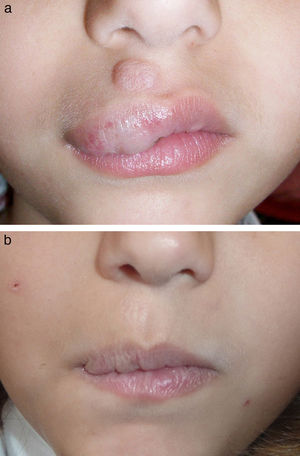

| 13 | Female | 7 y | Involuted | Upper lip | Surgery | 3 |

| 14 | Female | 13 y | Involuted | Left mandibular area | PDL | 1 |

| 15 | Female | 2 y | Involuted | Left cheek | Surgery, PDL | 2 |

| 16 | Female | 4 y | Involuted | Nose | PDL | 3 |

| 17 | Female | 8 y | Involuted | Neck | Surgery, PDL | 1 |

| 18 | Female | 5 y | Involuted | Left cheek | Propranolol, surgery | 1 |

| 19 | Female | 3 y | Involuted | Nose | Propranolol | 3 |

| 20 | Female | 2 y | Involuted | Forehead | Propranolol, PDL | 1 |

| 21 | Female | 6 y | Involuted | Upper lip | PDL | 1 |

| 22 | Female | 8 y | Involuted | Left arm | None | 1 |

The number of laser treatment sessions per patient ranged from 1 to 5 (mean, 2.04 sessions).

Adverse effects were seen in 4 patients (18.18%): mild atrophy (n=2), marked edema and ulceration in a hemangioma on the oral mucosa without subsequent residual scarring (n=1), and hyperpigmentation (n=1). Posttreatment transient purpura and mild edema, which occurred in most patients, were not considered adverse effects but rather expected responses to effective treatment. Table 2 summarizes the complications and improvement observed in each patient.

Degree of Improvement and Adverse Effects in Each Patient.

| Patient No. | Degree of Improvement | Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.5 | None |

| 2 | 1 | Mild atrophy |

| 3 | 5.5 | None |

| 4 | 1 | Mucosal ulceration (no residual scarring) |

| 5 | 1.5 | Mild atrophy |

| 6 | 1.75 | None |

| 7 | 4.5 | None |

| 8 | 2.25 | None |

| 9 | 1 | None |

| 10 | 2.5 | Hyperpigmentation |

| 11 | 1.75 | None |

| 12 | 9.75 | None |

| 13 | 3.75 | None |

| 14 | 3.75 | None |

| 15 | 4.25 | None |

| 16 | 7.75 | None |

| 17 | 7.5 | None |

| 18 | 6.75 | None |

| 19 | 5.75 | None |

| 20 | 4.75 | None |

| 21 | 3 | None |

| 22 | 2.5 | None |

Table 3 shows the improvement achieved with treatment in the entire group of 22 patients and in the various subgroups (patients with proliferative, involuting, and involuted hemangiomas). Values are expressed as median and IQR.

Degree of Improvement After Treatment in Entire Group and Subgroups of Patients.

| Total | Proliferative | Involuting | Involuted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR)a | 3.63 (1.75-5.56) | 1.0 and 3.5b | 1.75 (1.25-3.5) | 4.75 (3.75-7.5) |

aDegree of improvement was evaluated on a scale of 10 to 0.

bThe proliferative subgroup consisted of just 2 patients; the values shown correspond to one patient each.

The difference between the pretreatment and posttreatment values for the entire group of patients was statistically significant (P<.001). The variation was also statistically significant (P<.001) in each of the 3 subgroups.

The ICC among the 4 evaluators was 0.588 (95% CI, 0.385-0.773), indicating moderate, statistically significant agreement.

Figs. 1-4 show patients before and after treatment.

Treatment of infantile hemangiomas should be tailored to each patient on the basis of factors such as site, functional impairment associated with the lesion, likely future cosmetic impact, phase of development of the hemangioma, and request for active treatment by the patient's family. Accordingly, many infantile hemangiomas do not require pharmacological treatment or surgery and can be managed by watchful waiting, but some eventually do require some sort of intervention. As mentioned above, it is important to consider the phase of development of the hemangioma because not all current treatments are effective in all phases.

In recent years, the treatment of proliferative infantile hemangiomas has been revolutionized by propranolol, which is now considered the drug of choice.6–9 Previously, systemic or intralesional corticosteroids were considered the first-line treatment and other drugs such as bleomycin and interferon alfa were used to treat severe, recalcitrant lesions. Today, these medications are used only in exceptional cases to treat infantile hemangiomas. In some patients—for example, those with hemangiomas of the nasal tip—surgery remains an appropriate option.14

Laser treatment, especially with PDL, has also been used to treat hemangiomas in the proliferative phase. Numerous studies have confirmed the efficacy of PDL, especially for treating superficial hemangiomas, but its usefulness in the treatment of hemangiomas with a prominent deep component is more limited.15–19 Treatment with PDL may cause some adverse effects, including pigmentary changes and, more importantly, the possibility of ulceration and abnormal scarring.20 These complications seem to occur more frequently when PDL is used without a cooling system or to treat segmental hemangiomas. We therefore believe that PDL treatment should be administered by properly trained personnel in order to minimize these complications, especially in patients with segmental hemangiomas. Because of their longer wavelength (1064nm) and, therefore, greater depth of penetration, Nd:YAG lasers are also effective at treating proliferative hemangiomas with a prominent deep component, but their safety margin is smaller than that of PDL.21

In our series, we used dual-wavelength pulses from a PDL and a Nd:YAG laser to treat 2 patients with proliferative infantile hemangiomas with a prominent deep component; marked improvement was observed in both cases. Sequential application of a 595nm PDL followed by a 1064nm Nd:YAG laser has been shown to be effective at treating some capillary malformations resistant to conventional PDL treatment,22,23 cutaneous and mucosal venous malformations,24 angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia,25 and infantile hemangiomas.26 The response obtained with sequential application is due to the fact that PDL and Nd:YAG lasers have a depth of penetration of approximately 1mm and 5-6mm, respectively, and therefore reach structures at different dermal layers. Furthermore, PDL is used first. This reduces the oxygenated hemoglobin in the red blood cells to methemoglobin, causing a 3-fold to 5-fold increase in hemoglobin absorption by the Nd:YAG laser and making it possible to set the Nd:YAG laser at a lower fluence, thereby reducing the associated pain and edema.23,27,28 This approach can theoretically reduce the adverse effects associated with the use of Nd:YAG lasers as monotherapy because higher fluences increase the risk of atrophy and unattractive scarring associated with the loss of vascular selectivity.

Sequential PDL and Nd:YAG laser treatment is more painful than PDL as monotherapy. Local anesthesia is required in most patients, and general anesthesia may be indicated in patients with lesions that cover a large area. Topical local anesthetic was used in most of our patients, but a few patients aged less than 1 or 2 years with small infantile hemangiomas required no anesthetic.

The only study that has examined the use of sequential PDL and Nd:YAG laser treatment for infantile hemangiomas yielded promising results.26 The study describes the treatment of hemangiomas in 25 patients. Complete resolution without adverse effects was obtained in 18 patients, complete resolution with slight changes in skin texture or color in 4 patients, and incomplete resolution with possible associated scarring in 3 patients. It is important to note that the patients ranged in age from 3 months to 5 years and that their lesions were in different phases of development. We believe that the results of the treatment of proliferative hemangiomas cannot be considered comparable to the results of, for example, the treatment of telangiectasias in the involuted phase.

Beyond the proliferative phase, the treatment of hemangiomas is somewhat less standardized. Because infantile hemangiomas generally follow a course of progressive involution, a watchful-waiting approach is sufficient, although it should be noted that involution can take several years. Fifty percent of infantile hemangiomas have reached the involuted phase by the time the patient reaches age 5 years. However, residual lesions—ranging from nearly imperceptible alterations to severe disfigurement, plus the associated psychological impact—often persist beyond the involuting phase. Active treatment is therefore required in some cases.

Recent studies support the hypothesis that the use of propranolol beyond the proliferative phase can accelerate the involution of infantile hemangiomas.29 Treatment with PDL or Nd:YAG lasers has also been shown to be useful during the involuting phase. Unfortunately, because most studies on laser treatment for infantile hemangiomas have included patients ranging in age from a few weeks to several years, the real efficacy of laser treatment in patients with lesions in the involuting phase has not been well established. Our series included 9 patients with involuting hemangiomas, all of whom responded well to the treatment. It should be noted that the effectiveness of any therapeutic measure in patients with involuting hemangiomas is difficult to assess. Because the lesions always follow a natural course of spontaneous involution, it can be difficult to determine whether the treatment was responsible for the observed improvement. We believe that, in most of our patients, treatment with dual-wavelength pulses from a PDL and a Nd:YAG laser played a role in the improvement of the lesions because, in many cases, results were evident after only 1 or 2 sessions. Such improvement is unlikely to occur spontaneously in such a short time. Possibly even more difficult to predict is whether the improvement achieved with laser treatment would have eventually been obtained in the long term by spontaneous involution or if residual lesions would have persisted.

Treatment of residual hemangiomas varies according to the predominant component. Surgery may be indicated in cases where redundant fibrofatty tissue persists. In residual lesions characterized by skin texture changes and atrophic scarring, a therapeutic approach similar to that used to treat postacne atrophic scarring may be indicated. In several recent studies, fractional laser treatment has been shown to be effective in the treatment of such lesions.30 However, vascular laser treatment is clearly the first-line treatment in hemangiomas with a predominant vascular component. Lesions of this sort can be effectively treated with PDL, potassium-titanyl-phosphate lasers, or Nd:YAG lasers, all of which are effective in the treatment of telangiectasias secondary to various processes. The selection of one type of laser over the others may be influenced by factors such as vessel thickness and depth, the patient's skin phototype, and the clinician's experience with the various devices.

In our series, involuted hemangiomas were treated in 11 patients, 7 of whom had previously received PDL treatment for the residual vascular component. Because of its good safety profile, we consider PDL to be the first-line treatment for this type of lesion. However, for some lesions, particularly those consisting of large or deep vessels, the response to PDL treatment may be inadequate. We believe that dual-wavelength PDL and Nd:YAG laser treatment is a good alternative in these situations, as the results of this study show.

Despite the promising results, this study had some limitations that should be noted, such as the lack of a control group and the relatively small number of patients treated. Future research should include randomized trials to confirm the effectiveness and safety of the treatment. Another line of future research should explore the possibility of using lasers in combination with other treatments, such as propranolol, to determine whether the results obtained separately with each treatment can be optimized.

In conclusion, we believe that treatment with dual-wavelength pulses from a PDL and a Nd:YAG laser is a good treatment option for infantile hemangiomas in any phase of development when first-line therapies are ineffective or contraindicated.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed their hospital's protocol on the publication of data concerning patients and that all patients included in the study have received sufficient information and have given their written informed consent to participate in the study.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no private patient data are disclosed in this article.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors thank Abbott Laboratories for helping with calculations for the statistical analysis.

Please cite this article as: Alcántara-González J, et al. Hemangiomas infantiles tratados con aplicación secuencial de láser de colorante pulsado y Nd:YAG: estudio retrospectivo. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:504–11.