A 31-year-old man with a history of epilepsy (treated with valproic acid), alcoholism, and drug addiction visited the dermatology department with a mildly pruritic skin condition that had first appeared 45 days earlier on the forehead before spreading to the rest of his body. The patient also complained of general malaise.

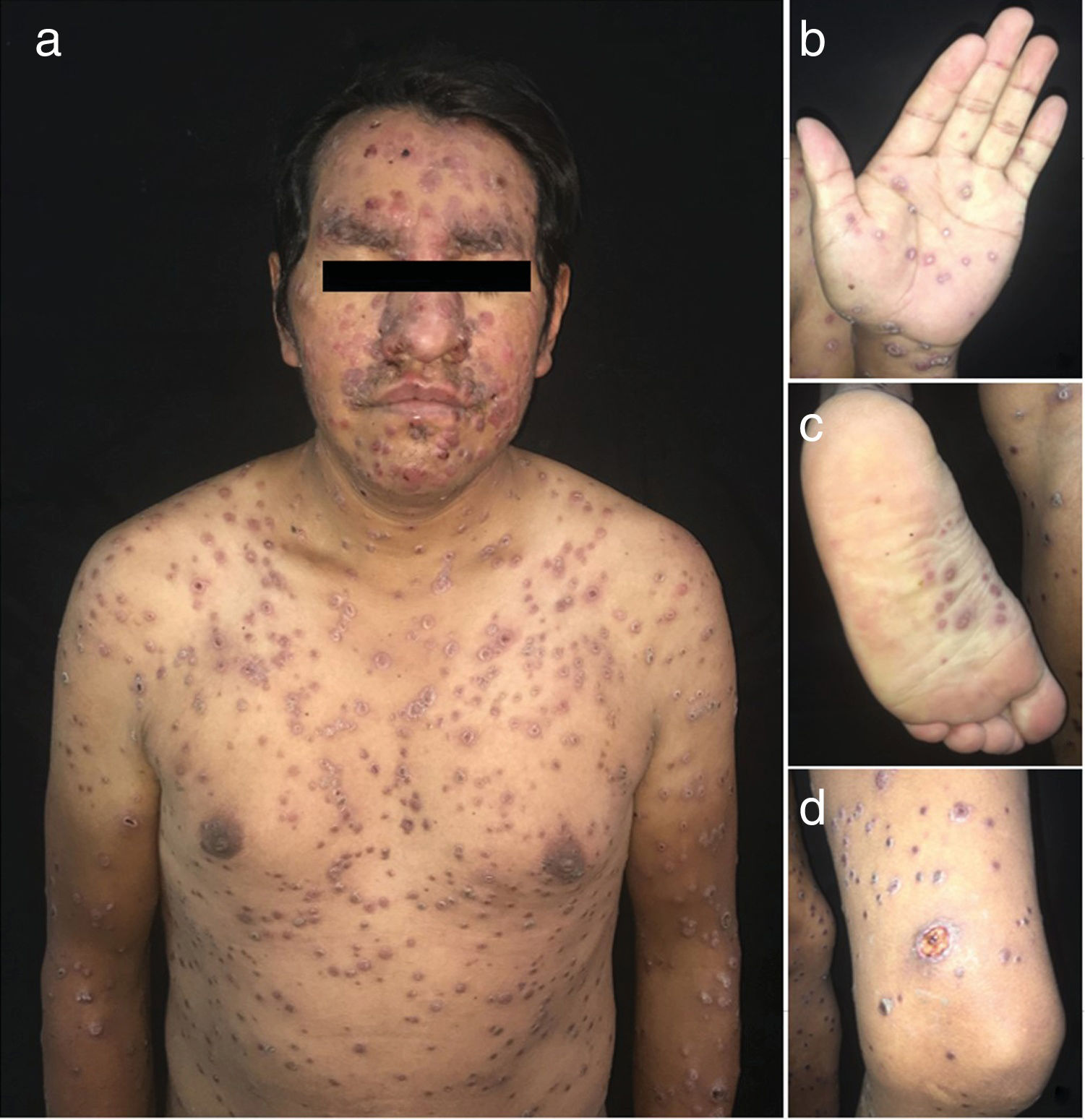

The physical examination revealed a disseminated rash characterized by smooth, well-defined, erythematous-violaceous nodules and papules with peripheral collarette scaling, some of which coalesced to form plaques. Well-defined ulcers with a violaceous border and dirty base were found on the back and left thigh. These were painful to touch (Fig. 1).

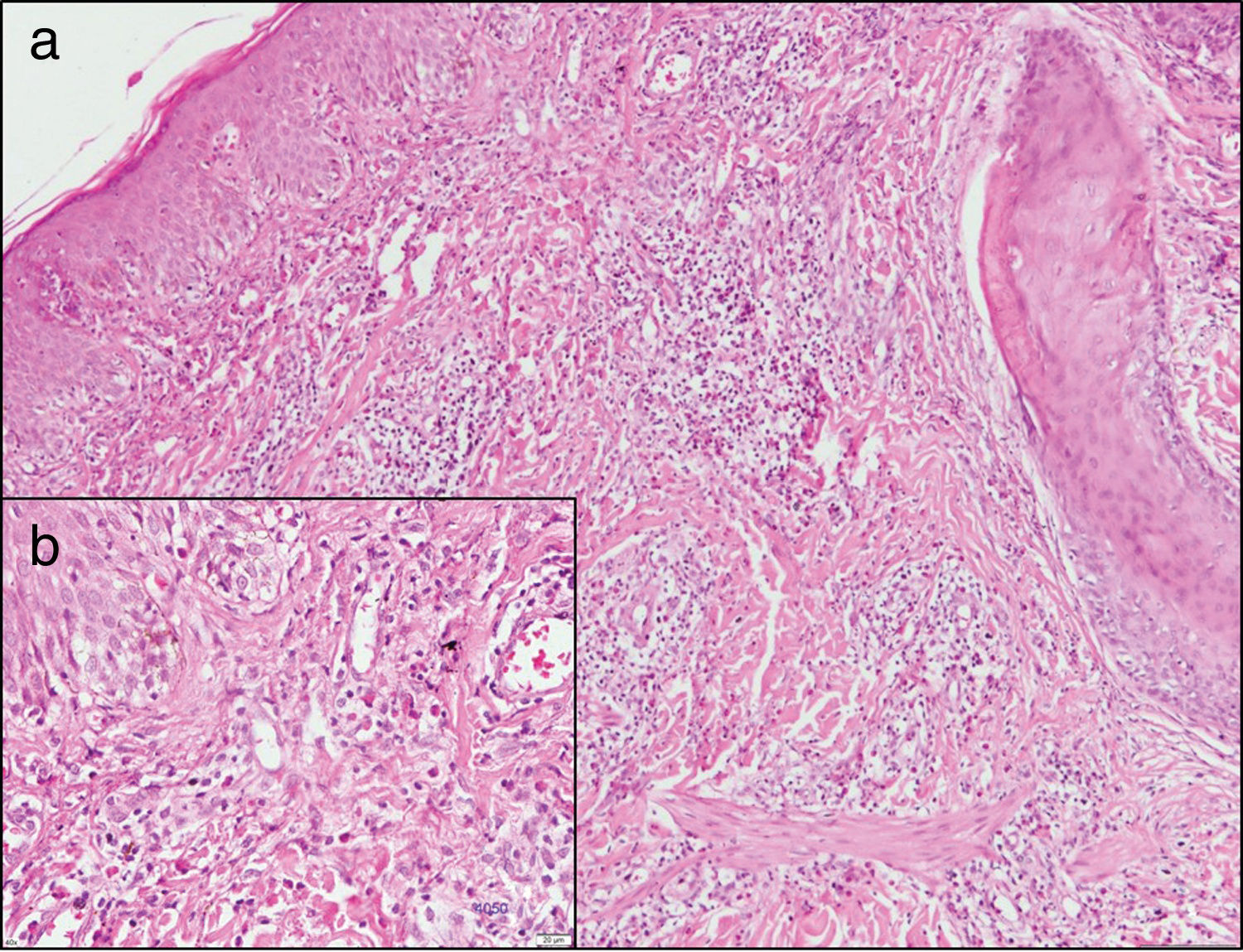

Microscopy with hematoxylin-eosin staining revealed ulceration of the epidermis, acanthosis, spongiosis, and a damaged basal layer, with microabscesses that open to the surface. A nodular, perivascular, and periadnexal inflammatory infiltrate comprising mainly plasma cells, lymphocytes, and histiocytes was observed in the superficial and deep dermis. These findings were compatible with secondary syphilis.

Warthin-Starry, May-Grünwald, and Giemsa staining did not reveal spirochetes.

The significant laboratory findings were as follows: venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test, positive (1/16 dilution); human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) p24 antigen assay, 482.80; CD4, 120 cells/µL; viral load, 2150 copies/mL; syphilis, 205.20.

The patient was diagnosed with malignant syphilis and HIV infection and prescribed benzathine penicillin 2 400 000 IU per week for 3 weeks. The treatment led to a self-limiting Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction that did not require treatment. At the end of treatment, the active lesions resolved, with multiple residual pigmented patches.

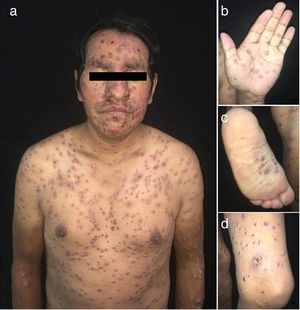

The patient did not attend the scheduled appointments for 11 months. He visited again with pruritic lesions on the arms and face that had first appeared 1 month earlier. The physical examination revealed localized dermatosis on the face and distal areas of the upper limbs. This was characterized by the presence of violaceous, infiltrated papules, some of which were excoriated and crusted (Fig. 2).

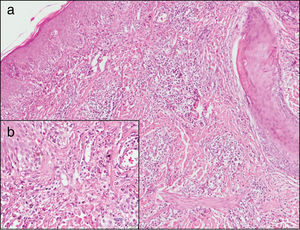

Laboratory testing revealed the following relevant findings: CD4, 151 cells/µL; viral load, 2315 copies/mL, and positive VDRL (1/2 dilution). A new biopsy revealed a hyperplastic and acanthotic epidermis, with focal vacuolization of the basal layer and abundant lymphohistiocytic infiltrate, as well as multiple eosinophils around the superficial and deep dermal vessels and hair and eccrine follicles, extending to the epithelium and to the subcutaneous tissue. These findings were compatible with pruritic papular eruption (PPE) (Fig. 3).

Skin biopsy of the new lesions. Hematoxylin-eosin. A, ×10. Note acanthosis, network hyperplasia, and focal vacuolization of the basal layer. Superficial and deep dermis, showing a perivascular and periadnexal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with exocytosis of numerous eosinophils into the epithelium that extends to the subcutaneous tissue. B, ×40. Detail of cellular infiltrate. Data compatible with pruritic papular eruption.

The correlation between the clinical and laboratory findings pointed to a diagnosis of HIV-associated PPE. Antiretroviral therapy was restarted, and symptoms were treated with oral antihistamines and topical corticosteroids. The patient’s condition improved markedly.

DiscussionSyphilis is a sexually transmitted infection that can present as primary, secondary, or tertiary disease.1 Secondary syphilis is characterized by generalized nummular erythematous macules mainly affecting the trunk, the proximal part of the limbs, the palms, the soles, and the mucous membranes. Also typical are patchy alopecia, fever, dysphagia, arthralgia, general malaise, weight loss, headache, and meningism. During this phase, the patient is highly contagious.2,3

Malignant syphilis is an ulcerative variant of secondary syphilis. It was first described in 1859 by Bazin. The word “malignant” stems from the clinical similarity between this disease and skin cancer, although it is not a cancer. Its incidence is unknown, and it is associated with immunodepression (HIV, diabetes), although not exclusively.1

Onset is at between 6 weeks and 1 year after the primary infection, or even earlier in immunodepressed patients. It is characterized by the presence of papules or pustules that easily become ulcerated. The ulcers are round or oval, with raised, well-defined borders and a necrotic or rupioid center. The rash may be associated with other symptoms, such as diarrhea, vomiting, and hepatosplenomegaly.4

While uncommon, malignant syphilis could be an early manifestation in HIV-infected patients with a CD4 T-lymphocyte count < 200 cells/µL.3,5

The diagnosis is usually confirmed based on the Fisher criteria, as follows: (1) compatible morphology; (2) positive serology test result for syphilis; (3) Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction to treatment; and (4) dramatic response to antibiotic therapy.6

Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is characterized by general malaise and fever associated with initiation of therapy. Pathophysiology is controversial, although it is thought to result from the inflammatory response that arises after the destruction of spirochetes, which is usually severe in HIV-infected patients. The reaction often occurs in patients receiving treatment for syphilis; nevertheless, it can also occur in other diseases, such as Lyme disease and leptospirosis.7

The recommended treatment is 3 doses of intramuscular benzathine penicillin 2 400 000 IU per week. Administration of systemic corticosteroids to prevent Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction has not been standardized, although several studies report use of methylprednisolone, hydrocortisone, and prednisone before the first dose of penicillin in order to prevent or relieve symptoms.2,7,8

Furthermore, PPE is associated with HIV infection. Its etiology is under study, and some studies indicate that in HIV-infected patients, it could be due to an altered immune response to insect bites.9 Farsani et al.10 reported the association between this disease and a CD4 T-lymphocyte count < 200 cells/µL, which is consistent with our findings.11

In summary, we report the case of a patient with malignant syphilis, an uncommon condition that may be the initial manifestation of immunosuppressive systemic diseases. We also highlight the need for follow-up of HIV-infected patients by the dermatology department, since this population is susceptible to developing skin conditions associated with inadequate control of the underlying disease, such as PPE.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Granizo-Rubio J, Caviedes-Vallejo C, Chávez-Dávila N, Pinos-León V. Sífilis maligna y erupción papular pruriginosa en un paciente VIH positivo. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;111:269–271.