Teledermatology is now fully incorporated into our clinical practice. However, after reviewing current legislation on the ethical aspects of teledermatology (data confidentiality, quality of care, patient autonomy, and privacy) as well as insurance and professional responsibility, we observed that a specific regulatory framework is still lacking and related legal aspects are still at a preliminary stage of development. Safeguarding confidentiality and patient autonomy and ensuring secure storage and transfer of data are essential aspects of telemedicine. One of the main topics of debate has been the responsibilities of the physicians involved in the process, with the concept of designating a single responsible clinician emerging as a determining factor in the allocation of responsibility in this setting. A specific legal and regulatory framework must be put in place to ensure the safe practice of teledermatology for medical professionals and their patients.

El ejercicio de la teledermatología ya se encuentra plenamente incorporado a nuestra práctica clínica. Sin embargo, tras revisar aspectos legislativos y éticos sobre confidencialidad, calidad asistencial, autonomía del paciente, privacidad, responsabilidad profesional y seguros en relación con la teledermatología constatamos que aún carece de regulación específica, estando los aspectos legales de la misma poco desarrollados. Garantizar la confidencialidad, la autonomía del paciente y la seguridad en el almacenamiento y envío de los datos son cuestiones imprescindibles para su práctica. La responsabilidad de los facultativos que intervienen en el proceso es uno de los principales motivos de controversia, siendo la figura del médico responsable determinante para decidir sobre la atribución de la misma. Es necesario el desarrollo de una regulación concreta para ejercer la teledermatología de forma segura para los profesionales y los pacientes.

Many doubts and questions still arise concerning the legal, ethical, and regulatory aspects of the practice of teledermatology. Moreover, many of them are still not addressed or regulated by the existing legal framework, where only very brief generic references are made to this practice. Key issues, including professional responsibility, data protection, and the ethics of care, need to be properly analyzed and formulated to ensure the safe practice of teledermatology with maximum guarantees for both patients and medical professionals. In this article, we offer a general overview of the medical and legal aspects of the practice of teledermatology.

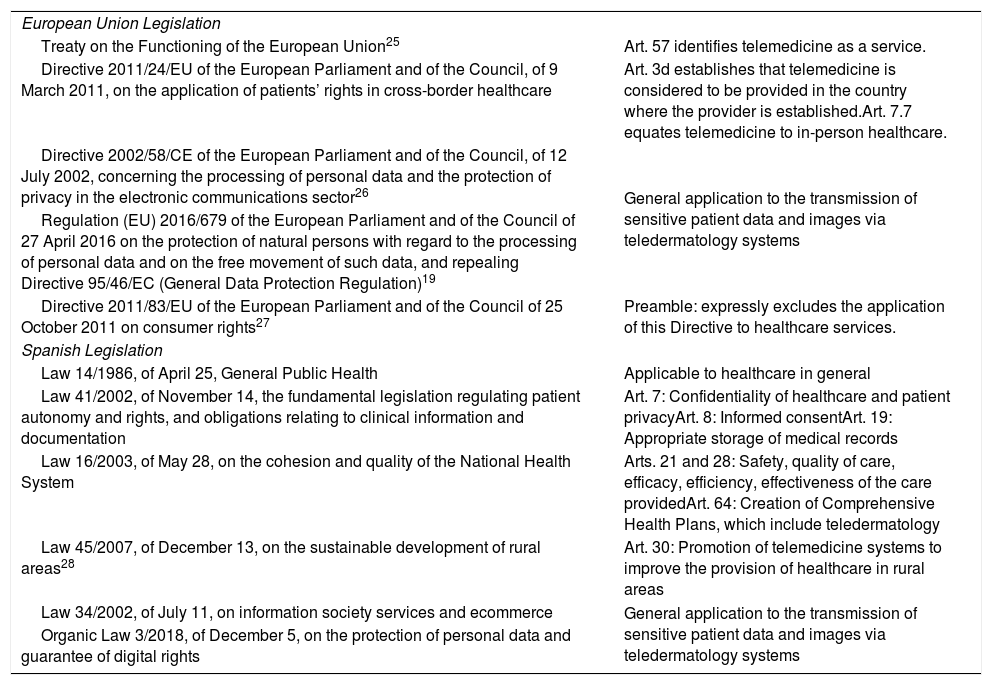

Regulation of TeledermatologyA review of European legislation and the current national and regional framework in Spain revealed no specific references to the practice of teledermatology. However, legislation relating to the practice of telemedicine in general applies, by extension, to teledermatology.

European Union LegislationThe European directive that deals most comprehensively with the regulation of telemedicine is Directive 2011/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council, of 9 March 2011, on the application of patients’ rights in cross-border healthcare.1 That directive indicates that in the case of telemedicine, healthcare is considered to be provided in the Member State where the healthcare provider is established (Art. 3d). It also equates remote practice with in-person care: “the Member State of affiliation may impose on an insured person […] including healthcare received through means of telemedicine, the same conditions, criteria of eligibility and regulatory and administrative formalities […] as it would impose if this healthcare were provided in its territory” (Art. 7.7).

Spanish LegislationSince teledermatology is a form of healthcare, it is, by default, subject to all the laws regulating the general aspects of the provision of healthcare services (Table 1).

Legislation Applicable, by Default, to the Practice of Teledermatology in Spain.

| European Union Legislation | |

| Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union25 | Art. 57 identifies telemedicine as a service. |

| Directive 2011/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council, of 9 March 2011, on the application of patients’ rights in cross-border healthcare | Art. 3d establishes that telemedicine is considered to be provided in the country where the provider is established.Art. 7.7 equates telemedicine to in-person healthcare. |

| Directive 2002/58/CE of the European Parliament and of the Council, of 12 July 2002, concerning the processing of personal data and the protection of privacy in the electronic communications sector26 | General application to the transmission of sensitive patient data and images via teledermatology systems |

| Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation)19 | |

| Directive 2011/83/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on consumer rights27 | Preamble: expressly excludes the application of this Directive to healthcare services. |

| Spanish Legislation | |

| Law 14/1986, of April 25, General Public Health | Applicable to healthcare in general |

| Law 41/2002, of November 14, the fundamental legislation regulating patient autonomy and rights, and obligations relating to clinical information and documentation | Art. 7: Confidentiality of healthcare and patient privacyArt. 8: Informed consentArt. 19: Appropriate storage of medical records |

| Law 16/2003, of May 28, on the cohesion and quality of the National Health System | Arts. 21 and 28: Safety, quality of care, efficacy, efficiency, effectiveness of the care providedArt. 64: Creation of Comprehensive Health Plans, which include teledermatology |

| Law 45/2007, of December 13, on the sustainable development of rural areas28 | Art. 30: Promotion of telemedicine systems to improve the provision of healthcare in rural areas |

| Law 34/2002, of July 11, on information society services and ecommerce | General application to the transmission of sensitive patient data and images via teledermatology systems |

| Organic Law 3/2018, of December 5, on the protection of personal data and guarantee of digital rights | |

No specific references to telemedicine were found in Law 14/1986, of April 25, on General Public Health2 or in Law 41/2002, of November 14, the fundamental legislation regulating patient autonomy and rights and obligations relating to clinical information and documentation in Spain.3 All the provisions of this act relating to patient privacy and the confidential nature of healthcare (Art. 7), informed consent, (Art. 8) and the appropriate storage of medical records (Art. 19), as well as other issues, also apply to telemedicine.

In addition, Law 16/2003, of May 28, on the cohesion and quality of the National Health System4 includes provisions regarding new healthcare technologies, which are subject to an evaluation with particular attention to their safety, quality, efficacy, efficiency, and effectiveness (arts. 21 and 28). The same act also provides for the creation of Comprehensive Health Plans, which could include teledermatology services (Art. 64).

Finally, given that teledermatology uses new information and communication technologies to store and transmit personal patient data, the practice is also subject to the provisions of Law 34/2002, of July 11, on information society services and ecommerce5 and Organic Law 3/2018, of December 5, on the protection of personal data and guarantee of digital rights.6,7

Ethics in the Practice of TeledermatologyThe Code of Medical Ethics of the General Council of Official Spanish Medical Associations approved in 20118 includes specific provisions on the practice of telemedicine:

“The clinical practice of medicine through consultations exclusively by letter, telephone, radio, newspapers or the Internet is contrary to the ethical standards. Correct practice must of necessity involve personal and direct contact […]. In the case of a second opinion or medical follow-up, […] the practice is ethically acceptable provided that both parties are clearly identified to each other and the patient’s privacy is guaranteed. The use of such remote technologies to provide patient guidance […] is consistent with medical ethics provided it is used solely as an aid to decision making. The rules of confidentiality, security, and secrecy shall apply equally to telemedicine […] (Art. 26).

However, the draft of the new Code of Medical Ethics of the General Council of Official Spanish Medical Associations,9 a document already at an advanced stage, which has been going through the approval process since 2018, recognizes the incorporation into routine practice of new technologies and the need for adequate training in their use: “The physician must recognize the transformative impact of […] the available health technologies and health applications. It is the duty of physicians to continually improve their knowledge of and proficiency in the skills that will enable them to use new technologies that have been shown to be of use and of benefit to patients” (Art. 102). The use of these systems will be considered ethical when such use complies with all the requirements that apply to any medical act: “[…] such use is in accordance with medical ethics provided that all the parties involved are clearly identified, confidentiality is guaranteed, and the means of communication used ensures the highest level of security available” (Art. 103): “[…] all the ethical precepts established in this Code relating to the doctor-patient relationship, the defense of the patient’s rights and safety, and respect for health professionals also apply” (Art. 104). Healthcare professionals must also assume liability for any harm resulting from healthcare services delivered via teledermatology systems just as they do for services delivered in person and face-to-face: “When physicians use communication systems, they must be aware of the implications of their actions and of the direct or indirect damages that may result from the service and they must accept legal and ethical responsibility for any such damage” (Art. 105).

The Clinical Practice of TeledermatologyProfessional Responsibility: InsuranceIn certain circumstances, it has been considered that in the case of a teleconsultation between two healthcare professionals, responsibility for the final clinical decision lies with the physician who requests the consultation.10 In such cases, the dermatologist is deemed to be providing clinical advice at the request of the primary care physician,11 and it is the latter who is ultimately deemed to be the responsible physician. The term responsible physician (médico responsable) is defined in Law 41/2002, of November 14,3 as follows: “the professional who is responsible for coordinating the information and healthcare of the patient or user and is the principal interlocutor […] during the care process, without prejudice to the obligations of other professionals involved in the patient’s care” (Art. 3).

In other circumstances, teleconsultation has been considered to be just one more exploration in the care process, recognizing the responsible physician’s duty to consult a dermatologist if diagnostic doubts arise during the process.12

Other authors have made the point that a failure to use rapid means, such as teledermatology, could constitute a breach of professional responsibility if such means were not used when available and when failure to use them might lead to a delay in diagnosis or therapy to the detriment of the patient’s health.13

It is also important for health professionals to ascertain whether the liability or malpractice insurance covering their work includes coverage for the remote provision of healthcare services.12,14

It is generally understood that teledermatology is covered by such policies in the same way as any other healthcare activity. In the case of remote consultations, however, it is important to take into account the geographical limits of the coverage. Healthcare provided in Spain and claims made before Spanish courts may be covered by the policy while care provided to a patient located in another country or to a foreign patient who subsequently makes a claim before a foreign court would be excluded from the coverage of the policy, unless the insurance company expressly accepts such claims.

Security, Quality of Care, and Clinical Data ProtectionSeveral authors have highlighted the need for teledermatology to be integrated into a care process that includes a protocol for periodic assessment and validation to guarantee clinical safety and quality control15–17 and requires a dermatologist to be available to provide in-person care when needed. Nevertheless, given that remote care may possibly reduce diagnostic certainty, giving rise to more diagnostic errors, caution is recommended in the use of this modality.15

One fundamental aspect of remote healthcare is ensuring the confidential transfer of images and personal patient data (particularly when this contains identifying information) through the use of encryption systems, access limitations,12 and secure delivery methods15 in accordance with Spanish and European legislation on patients’ rights. All electronic equipment and imaging systems used must be properly maintained to minimize, as far as possible, any medical error that could arise from their malfunction.18

Patient Autonomy and Informed consentIn teledermatology, as in any other form of medical care, patient autonomy must be respected; informed consent is the basic, indispensable instrument through which this principle is applied. Since telemedicine involves the transfer of digital images and data that may include identifying information, the patient must also be informed how the care model works and be properly informed by the consulting doctor. Written informed consent is not required for the practice of teledermatology because it is not one of the cases specified in Law 41/2002, of November 143: “surgical intervention, invasive diagnostic and therapeutic procedures and […] procedures that involve risks or inconveniences that may have a foreseeable and well known negative impact on the patient’s health” (Art. 8.2). However, under current European and Spanish data protection legislation,6,19,20 patients must be informed if an image that could identify them is to be used for teaching or scientific purposes and they must explicitly authorize any such usage. Clinical photographs are treated in the same way and subject to the same restrictions as any other component of the patient’s medical record.20

Teledermatology in Emergency Situations: Use During the COVID-19 PandemicThe rapid worldwide spread of SARS-CoV-2 and the emergency measures taken to control the pandemic have greatly limited the provision of in-person healthcare.

In these circumstances, teledermatology is a very useful tool for facilitating the continuity of care while avoiding in-person contact and patient travel.21 Royal Decree-Law 8/2020, of 17 March, on urgent extraordinary measures to address the economic and social impact of COVID-19,22 establishes a legal framework for the provision of services and the continuation of work activity by means of teleworking (Art. 7). The practice of teledermatology falls into this category.

Given the growth in the use of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Central Commission of Medical Ethics of the Spanish Medical Association issued a communiqué23 with a series of recommendations on the use of telemedicine; that statement considers it to be an effective and accessible model that takes advantage of new technologies for the benefit of patients at a time when face-to-face care is either not possible or the risks involved outweigh the benefits. To ensure proper remote care, all teleconsultations should be agreed with the patient, the professionals involved should be properly identified, and the consultations should be recorded in the patient’s clinical history. Ensuring patient privacy and confidentiality at all times is a priority. When, for clinical reasons, the medical professional considers an in-person visit to be necessary, they shall make an appointment to see the patient for a face-to-face assessment. It is, nonetheless, clear that many ethical and legal questions still need to be answered.

Furthermore, to date no European standards in the form of regulations, instructions, or recommendations, have been approved regarding the use of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In the United States, the Office of Civil Rights (OCR) has indicated that restrictive criteria will apply to the admission of data protection and privacy claims if a telemedicine system has been used in good faith to treat Medicare patients during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Furthermore the OCR has stated that it will not consider the practice of telemedicine using communication applications (Apple FaceTime, Facebook Messenger, Google Hangouts, or Skype) to contravene existing U.S. data protection legislation—that is, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Finally, the OCR has recommended that healthcare professionals should, however, advise their patients that these systems may not be suitable for the secure transmission of data and images, although it is not mandatory to communicate this risk.24

DiscussionIn short, the practice of teledermatology has advanced and moved beyond its specific legal framework, giving rise to numerous ethical and legal issues that continue to give rise to controversy.

Some authors consider the restrictive view of telemedicine enshrined in the codes of ethics to be too strict and advocate for the broader use of this modality to complement in-person care, for planning and prioritization and any other purpose that can improve the delivery of care.7 This is the prevailing view in our country’s public health systems. The new draft Code of Medical Ethics and Deontology is sensitive to this shift and introduces new provisions for the ethical regulation of teledermatology appropriate to the current situation.

In teledermatology, the prevailing opinion regarding professional liability is that the consulting physician is the professional ultimately responsible for decisions on the management of the case; however, this should not lead us to overlook the fact that Law 41/2002, of November 14,3 states that these actions are carried out without prejudice to the obligations of the other professionals who participate in the care of the patient, (Art. 3), which means that a dermatologist responsible for an erroneous recommendation in the context of a teleconsultation could be found responsible and be obliged to accept liability for the complaint, depending on the circumstances of the case.

Clear and specific legal guidelines are needed to ensure that specialists can practice teledermatology in a setting that is safe for both the patient and the clinician, with clear delimitation of the responsibilities of the professionals involved and respect for both patient rights and the value of the in-person doctor-patient relationship as the cornerstone of medical practice.

Conclusions- 1

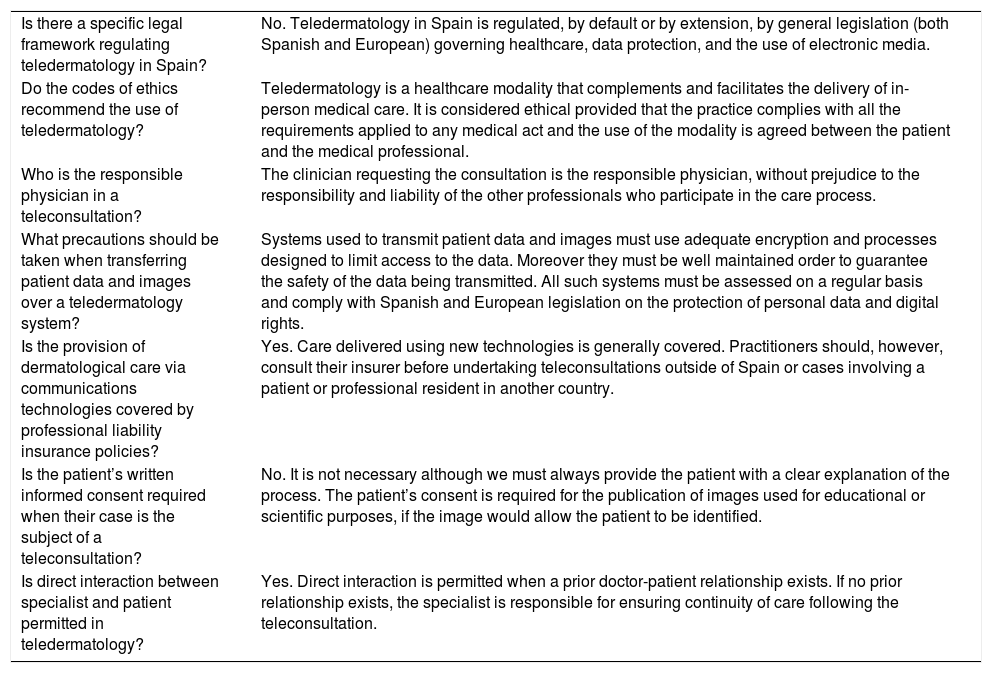

At present, despite the growth in various forms of telemedicine, there is no specific legislation regulating these healthcare services in Spain, with the result that remote modalities are at present regulated by the provisions of non-specific legislation applied subsidiarily (Table 2).

Table 2.Frequently Asked Questions About the Medical and Legal Aspects of Teledermatology in Spain.

Is there a specific legal framework regulating teledermatology in Spain? No. Teledermatology in Spain is regulated, by default or by extension, by general legislation (both Spanish and European) governing healthcare, data protection, and the use of electronic media. Do the codes of ethics recommend the use of teledermatology? Teledermatology is a healthcare modality that complements and facilitates the delivery of in-person medical care. It is considered ethical provided that the practice complies with all the requirements applied to any medical act and the use of the modality is agreed between the patient and the medical professional. Who is the responsible physician in a teleconsultation? The clinician requesting the consultation is the responsible physician, without prejudice to the responsibility and liability of the other professionals who participate in the care process. What precautions should be taken when transferring patient data and images over a teledermatology system? Systems used to transmit patient data and images must use adequate encryption and processes designed to limit access to the data. Moreover they must be well maintained order to guarantee the safety of the data being transmitted. All such systems must be assessed on a regular basis and comply with Spanish and European legislation on the protection of personal data and digital rights. Is the provision of dermatological care via communications technologies covered by professional liability insurance policies? Yes. Care delivered using new technologies is generally covered. Practitioners should, however, consult their insurer before undertaking teleconsultations outside of Spain or cases involving a patient or professional resident in another country. Is the patient’s written informed consent required when their case is the subject of a teleconsultation? No. It is not necessary although we must always provide the patient with a clear explanation of the process. The patient’s consent is required for the publication of images used for educational or scientific purposes, if the image would allow the patient to be identified. Is direct interaction between specialist and patient permitted in teledermatology? Yes. Direct interaction is permitted when a prior doctor-patient relationship exists. If no prior relationship exists, the specialist is responsible for ensuring continuity of care following the teleconsultation. - 2

The codes of ethics have evolved from a restrictive approach to the use of teledermatology to accepting its incorporation as an accessible, efficient, and safe tool that complements face-to-face care. Its use is now deemed ethical provided the patient is informed and agrees and his or her confidentiality and privacy are guaranteed.

- 3

The concepts of informed consent and respect for patient autonomy apply to teledermatology in the same way as they do to any other form of care. The importance of protecting the confidentiality and privacy of patient data and images sent through computer systems is recognized as a requirement for the safe practice of teledermatology.

- 4

The consulting physician, in accordance with the concept of responsible physician, is the professional ultimately responsible for the care provided through a teledermatology system.

- 5

It is recommended that all professionals who participate in teledermatology systems should ensure that their liability or malpractice insurance covers healthcare services provided remotely.

- 6

Teledermatology must be integrated into a health service delivery system that guarantees continuity of care after a teleconsultation. This issue is particularly relevant in the case of direct doctor-patient teledermatology consultations in private healthcare settings.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to acknowledge the help of the professional liability section of the Illustrious College of Physicians of Cordoba for their help on the question of insurance coverage.

Please cite this article as: Gómez Arias PJ, Abad Arenas E, Arias Blanco MC, Redondo Sánchez J, Galán Gutiérrez M, Vélez García-Nieto AJ. Aspectos medicolegales de la práctica de la teledermatología en España. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021;112:127–133.