Several years ago when we began our quest to locate the Olavide Museum wax models, many dermatologists knew that the museum had initially been set up in the former Hospital de San Juan de Dios (on Plaza de Antón Martín) and subsequently transferred to a new location (Calle del Dr Esquerdo, today, Calle de Gregorio Marañón), that the number of figures was unknown (some suggested 1500, others 400), and that the museum had been closed down in the 1960s, after which time it slipped slowly into a period of administrative and dermatological oblivion. We also knew that Dr José Eugenio de Olavide y Landazabal had championed the creation of the museum and that most figures had been produced by sculptor Enrique Zofío Dávila and others by José Barta y Bernadotta. This rough sketch describes most of the historical knowledge generally spread by word of mouth among dermatologists in the absence of documented evidence.1

On December 27, 2005, after years of research, we located many of the figures from the collection packed away in wooden boxes at the Hospital del Niño Jesús. To our surprise, several boxes contained no figures but abundant documentation. When we analyzed the documents, we began to wonder about the origin and creators of these figures. We then contacted Zofío and Barta's families, who provided us with a great deal of information and more documents. However, about a third sculptor, Rafael López Álvarez, we were only able to locate a small newspaper reference indicating that he had been responsible for closing down the museum and packing away the figures in 19661 (Fig. 1).

Then began the arduous task of poring over scholarly studies of various types, visiting official bodies, and collecting all kinds of information about the Hospital San Juan de Dios, the Olavide Museum, Dr Olavide, Zofío, and possibly other sculptors. With that in mind, we consulted the doctoral theses of Drs J. J. Padrón LLeo, E. Del Río de la Torre, J. García Cubillana, and F. Heras Mendaza2–5; all these magnificent studies concerned the Hospital San Juan de Dios and Olavide Museum.

We also used Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas to guide us, as our journal had published excellent, detailed studies by Drs Del Río and A. García Pérez,6–10 and we located other publications by Drs X. Sierra Valentí and J. Calap Calatayud.11–14 Each provided us with fresh references to studies that had preceded them, enabling us to gradually add details, dates, and characters to this story, despite frequent contradictions in the record.

From the papers consulted we know that the Olavide Museum was inaugurated on December 26, 1882, and that it was closed in 1966 by the last restorer-sculptor López Álvarez (Fig. 2), about whom very little is known, though he was closest to us in time. We also confirmed that numerous figures were produced by Barta, who was possibly a pupil of Zofío's, although curiously enough the two sculptors signed none together. Barta produced several with López Álvarez, however.

The information about Dr Olavide and his life is quite extensive and complete, and for this reason we will focus on the museum's sculptors in this paper.

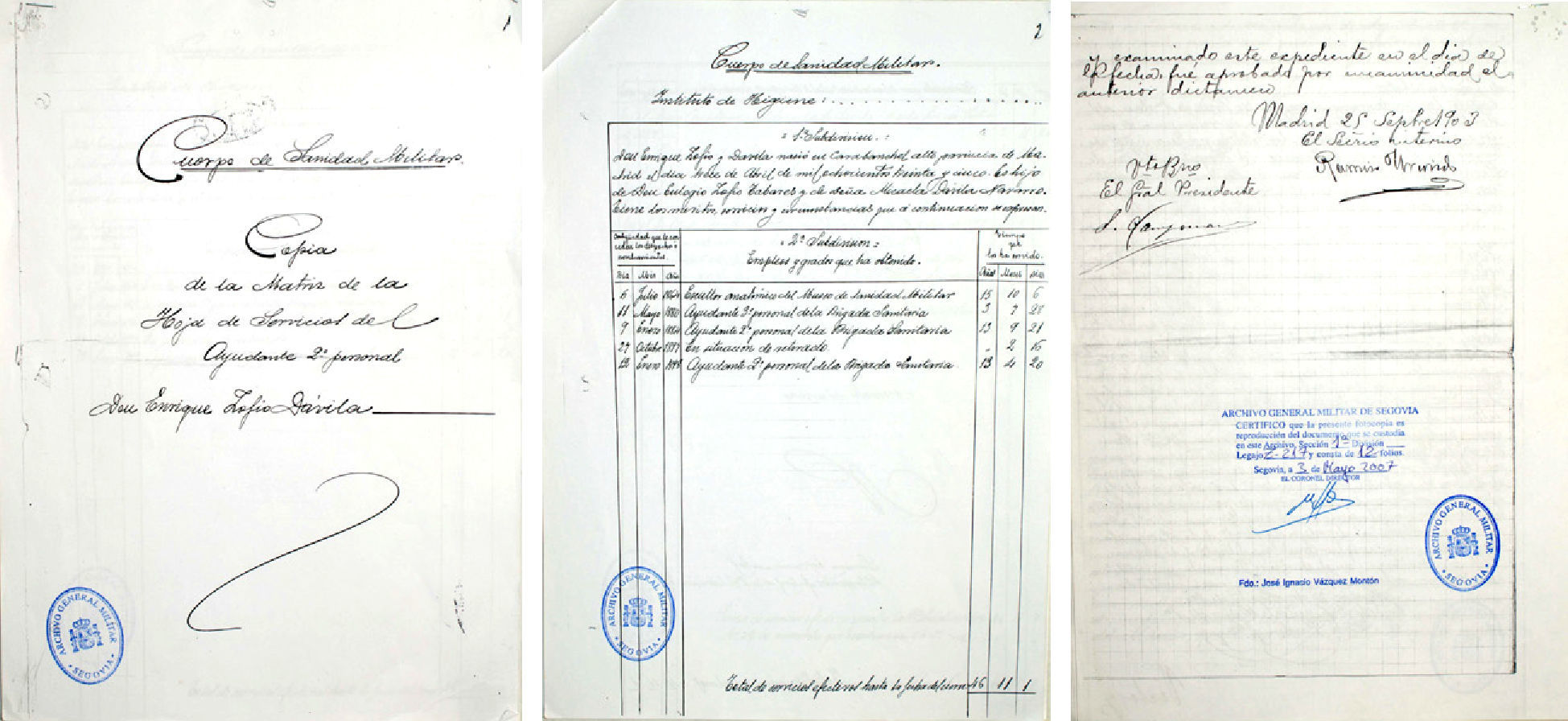

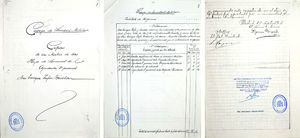

Zofío and Barta are not common surnames, so we first turned to such sources as the telephone directory, registry office and burial records, and successfully located direct descendents: a great-granddaughter and a grandson, respectively. They shed considerable light on the sculptors’ family backgrounds but very little on their professional lives. Zofío's kin passionately recalled his dedication and military career (the family owns a portrait in oil depicting him in uniform). Armed with these details, we set off for the military record office (Archivo Militar) in Segovia, where we found his record of service with the Spanish army's medical corps from July 6, 1864 to May 31, 1911. We discovered that he was a civilian under contract and not a professional soldier—as his portrait in military dress, decorated with three medals, had originally led us to believe (Fig. 3).15

This document proved vital for unearthing information about Zofío's life and, as we shall see later, many questions about the origin of the figures and the relationship between Zofío, the Hospital San Juan de Dios, and Dr Olavide emerged in consequence.

The military's file for Zofío also led us to research publications on the history of the Spanish medical corps and military hospitals and museums, particularly the Hospital Militar de Madrid-Carabanchel, where Zofío worked for much of his career and where he created numerous anatomical figures, among them the dermatologic wax models.16,17

Thanks to these documents we now have an accurate picture of Zofío's professional activities, including various promotions, awards, and 2 trips to Paris. In 1878, he visited the universal exhibition as advisor on designs and sketches (possibly for anatomical models), with Dr Cesáreo Fernández Losada (who would subsequently also work on the wax models) and Dr Nicasio Landa. The work they presented was much admired by visitors to the Paris exhibition.

Zofío's second trip, in 1882, was taken to hone his skills in workshops where anatomical figures were produced. Neither of these visits coincided with the 1889 journey the 2 Castelos (Drs Eusebio Castelo Serra and Fernando Castelo Canales) and the 2 Olavides (José Eugenio and José) made to the 1889 First International Congress of Dermatology and Syphilology in Paris, where 90 figures from the Olavide Museum (almost certainly by Zofío) were displayed and received high praise.

This information has led us to believe that Zofío started out as a sculptor for the military, working with or under the orders of Fernández Losada to produce anatomical figures for several military hospitals. There is also a veiled reference to wax models in dermatology. Subsequent inventories, including such details as numbers and titles, were made in 1908, 1909, and 1910, and again on Zofío's retirement in 1911.17

Zofío carried out most of his work on the sculptures from 1880 to 1897, during the period when the Hospital San Juan de Dios moved (to Calle del Dr Esquerdo). Fortunately for us, all are accompanied by a wealth of clinical data (medical history, treatment, and patient provenance, year, bed number, name of the doctor who wrote the clinical notes, etc.). Two questions now emerge: Where did Zofío make the figures and how was he connected to the Hospital San Juan de Dios?

The absence of details or documents associating Zofío with the hospital in any professional capacity is certainly curious. Where the figures were made is another mystery, as there is no indication that he had a space for working on them at the first location of Hospital San Juan de Dios (Plaza de Antón Martín). The photographs we found of the Olavide Museum workshop seem to correspond to the second location (Calle del Dr Esquerdo, 1901-1967). This theory is supported by Dr Juan de Azúa Suárez's autobiography, when he says: “In 1887 I was working at San Juan de Dios as a locum tenens, and in 1889 I took great interest in seeing dermatology patients in a manner of coal shed (the ceiling was 1.70 m high) with a waiting room in the water closet.”12 This then leads us to question whether a hospital would give a sculptor and outsider like Zofío a space larger than that of a department head of Azúa's temperament. So we must also ask how, if the sculptor was working for the military, he gained access to the patient's bedside for the purpose of creating his models?

The fact is that the figures Zofío produced at that time are all associated with doctors on staff at the Hospital San Juan de Dios (Drs M Sanz Bombín, Olavide, Azúa, and 1 of the Castelos) and all accompanying information: a clinical history that includes a bed number, name of the physician writing the notes, date of admission, discharge, and treatment. It is also interesting that some models relate to cases in the private practices of Drs Olavide, Azúa, Fernández Losada, and so forth, and it is curious that in some cases a label from the Olavide Museum was placed over one naming Fernández Losada.

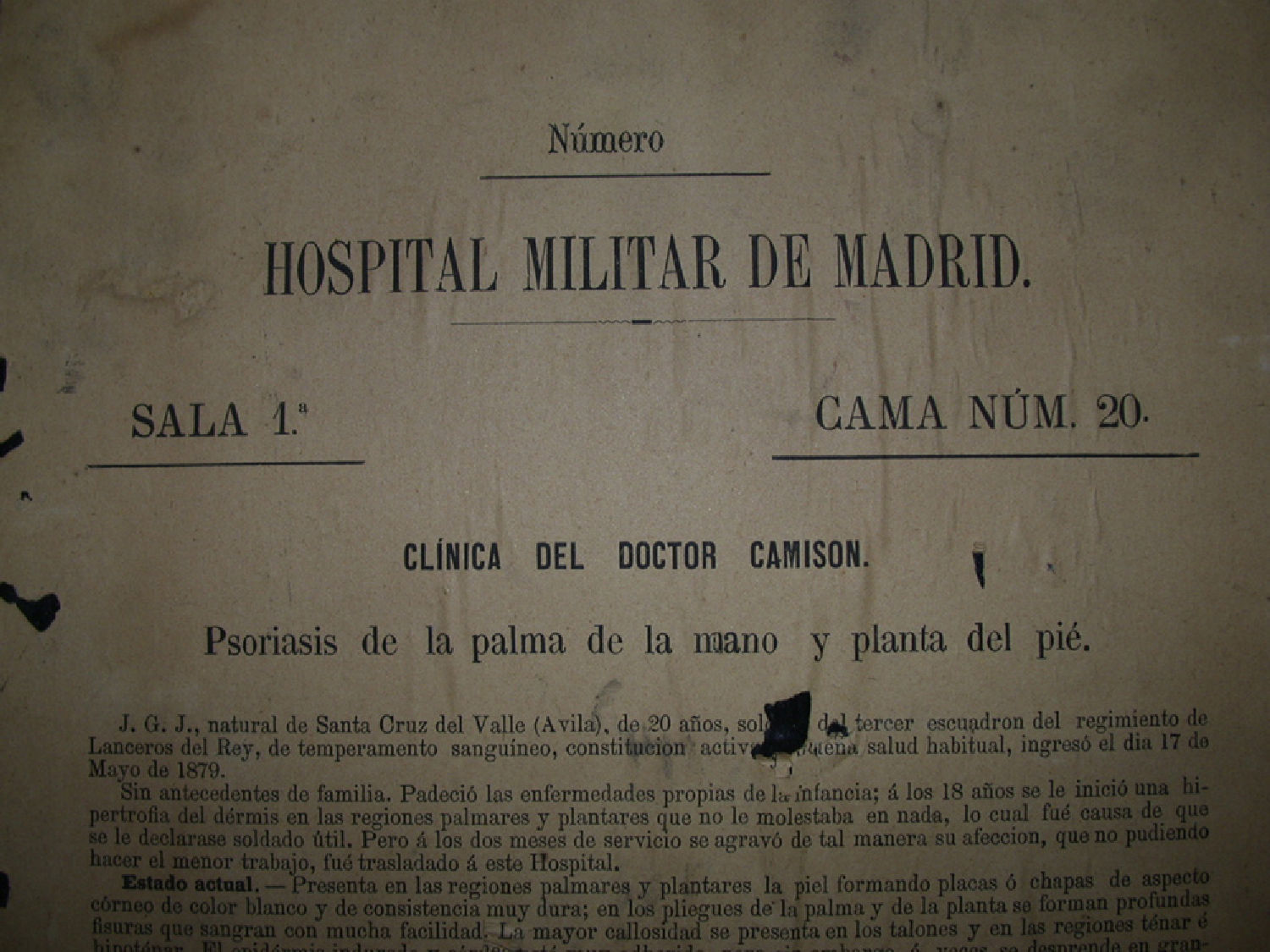

A further degree of complexity was introduced when we discovered that Granada had faithful copies of some of the models found in Madrid, some bearing a label referring to a Losada Anatomic Musem and giving a Madrid street address (“Progreso 5”), while others were labeled “Enrique Zofío, sculptor, Madrid” (Fig. 4).

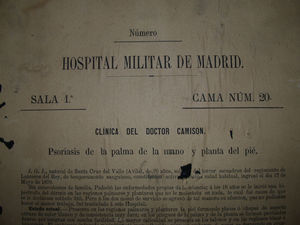

The accompanying information in the second case matches that of the Granada model (in that the same paper and writing is used), even though the label gives the provenance as the Hospital Militar de Madrid, with indication of the ward, bed, and the fact that the clinician is in some cases a Dr Camisón, who we believe was not attached to the military Hospital San Juan de Dios (Fig. 5).

Another very important but complicating detail is that on February 8, 1889, a former university preparatory facility (Seminario de Nobles) whose premises housed the Hospital Militar de Madrid and the pathology museum (Museo Anatomopatológico), went up in flames. According to the studies we reviewed, virtually the entire content of the museum was destroyed. Around 1151 pieces were lost but the type—whether they were general anatomical figures or the wax models of dermatologic conditions—is not recorded. The figures that were saved remained for a time at the military's preventive medicine facility (Instituto de Higiene Militar), part of the Hospital Militar de Madrid, but were then moved in 1898 to a private house in the city (at Paseo de Rosales, number 12). In 1901, they eventually reached the new Hospital Militar de Madrid-Carabanchel, where painter-sculptor Zofío was curator and entrusted with organizing a new pathology museum.15,16

For a time, the museum grew as it acquired material, including collections from other military museums. Interestingly, annual reports mention wax models by Zofío and the possible addition of museum sections on dermatology, syphilography, normal anatomy, pathology, and others.

However, the newly established military medical school (Academia Médico Militar) began to press for the creation of a history section and so the models were initially transferred there but were later moved to the medical equipment and preventive medicine section (Higiene y Material Sanitario). In 1917 there was a military medicine museum (Museo de Sanidad Militar) in Carabanchel, and the pathology museum there was in evident decline in the absence of a curator after Zofío's retirement. The history section, however, was in full expansion and supported by the military authorities, who took over the medical equipment and preventive medicine museum and eventually established the military medicine museum in 1918. It is not known whether the pathology exhibits were transferred to the military's medical school, but certainly nothing more was ever heard of that collection.

According to the family of Barta y Bernadotta (1875-1955), this sculptor came from an artistic family of actors and musicians, was a fairly well-established painter, and was awarded a medal by the Madrid fine arts circle (Círculo de Bellas Artes). However, we have no knowledge of when he began to work at the museum, as the figures he produced are unaccompanied by a patient's medical history or details other than the title. We do know, however, that he created models with López Álvarez, but not with Zofío, and that he was already at the museum in 1927 because of scenes from a film about venereal disease (La terrible lección, 1927), in which he appears guiding several people, including Drs Julio Bejarano and José Sánchez Covisa, through the museum.18

The material we have been able to study allows us to be fairly confident of the following statements and raise corresponding questions:

- 1

Most if not all of the models belonged to the Hospital San Juan de Dios.

- 2

Zofío was the linchpin that connected the military medicine museum to the Olavide Museum.

- 3

Zofío was under contract to the army for his entire career, but his working relationship with the Hospital San Juan de Dios and the museum remains to be clarified.

- 4

Zofío was an anatomical sculptor who went on to make wax figures in dermatology and, like many sculptors of the time, produced and sold copies to other museums or medical centers.

- 5

Some figures bear Fernández Losada's stamp but were made by Zofío. What was the working relationship between the two? We know that Fernández Losada was a physician and founder of the military medical school, the pathology museum, and the bacteriology institute (Instituto Bacteriológico). However, in his early years, he was also a reputable anatomical sculptor and invented a ceramic paste that bears his name.

- 6

According to the documents reviewed, it is not clear whether all the wax models were destroyed in the 1889 fire at the Hospital Militar de Madrid. If not, what happened to them en route to the Hospital de Madrid-Carabanchel in 1901 remains a mystery.

- 7

The question of what happened to the figures from the museum of the Hospital Militar de Madrid-Carabanchel until they were transferred to the Military Hospital of the military medical school in 1917 also still remains to be answered.

- 8

Did some of the figures found in Granada come from the museum of the Hospital Militar de Madrid-Carabanchel?

Perhaps this is also true for some figures at the Olavide Museum. Supporting this hypothesis is the discovery of 2 loose records bearing the same numbers as other bound records stating that figures came from the Hospital Militar Clínica of Drs Camisón and Pérez de la Fanosa. We have not found the 2 figures implied in the records.

The above statements and hypotheses are based on our research to date. It is important to point out, however, that 60 boxes from the Olavide Museum have yet to be opened. Many contain documents and we may unearth clues or details that will require us to correct some of the information outlined above.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors thank Amaya Maruri and David Aranda, restorers of the Olavide Museum models, for their assistance.

Please cite this article as: Conde-Salazar Gomez L, Heras-Mendaza F. Nuevas aportaciones a la historia del Museo Olavide y sus figuras. Actas Dermosifiliogr.2012;103:561-566.