The main aim of this study was to identify predictors of sentinel lymph node (SN) metastasis in cutaneous melanoma.

Patients and methodsThis was a retrospective cohort study of 818 patients in 2 tertiary-level hospitals. The primary outcome variable was SN involvement. Independent predictors were identified using multiple logistic regression and a classification and regression tree (CART) analysis.

ResultsUlceration, tumor thickness, and a high mitotic rate (≥6 mitoses/mm2) were independently associated with SN metastasis in the multiple regression analysis. The most important predictor in the CART analysis was Breslow thickness. Absence of an inflammatory infiltrate, patient age, and tumor location were predictive of SN metastasis in patients with tumors thicker than 2mm. In the case of thinner melanomas, the predictors were mitotic rate (>6 mitoses/mm2), presence of ulceration, and tumor thickness. Patient age, mitotic rate, and tumor thickness and location were predictive of survival.

ConclusionsA high mitotic rate predicts a higher risk of SN involvement and worse survival. CART analysis improves the prediction of regional metastasis, resulting in better clinical management of melanoma patients. It may also help select suitable candidates for inclusion in clinical trials.

El objetivo principal de este estudio es identificar factores predictivos de la afectación metastásica del ganglio centinela (GC).

Pacientes y métodoSe trata de un estudio de cohortes retrospectivo realizado en 2 centros hospitalarios de tercer nivel. Se incluyeron un total de 818 pacientes. La medida de resultado principal fue la afectación del GC. La valoración de predictores independientes de esta afectación se realizó mediante una regresión logística múltiple y un árbol de clasificación y regresión (CART).

ResultadosEl análisis de regresión logística múltiple mostró que la ulceración, el grosor tumoral y un alto índice mitótico (IM) (≥6 mitosis/mm2) se relacionaron con la afectación metastásica del GC de forma independiente. El CART mostró que el grosor de Breslow fue el factor más importante como predictor de la afectación linfática. Para los melanomas gruesos (>2mm) las variables predictoras fueron la ausencia de infiltrado inflamatorio, la edad y la localización. Para los melanomas menores de 2mm las variables predictoras fueron el IM (>6mitosis/mm2), la ulceración y el grosor. El grosor tumoral, la edad, la localización y el IM fueron predictores de la supervivencia de estos pacientes.

ConclusiónUn alto IM se asocia con una mayor afectación metastásica del GC y una peor supervivencia. Con la metodología CART es posible una mejor predicción de la afectación metastásica regional con vistas al mejor manejo clínico de estos pacientes o su inclusión en ensayos clínicos.

Sentinel lymph node (SN) metastasis is currently the most important predictor of survival in patients with melanoma.1 Although early dissection of affected lymph nodes has not been proven to improve overall survival,2 it is accepted that knowledge of regional involvement permits a more accurate prognosis and helps in the planning of treatment.3

Breslow thickness and presence of ulceration have been systematically linked to a higher likelihood of SN involvement in melanoma.4–7

In recent years, however, mitotic rate has gained increasing recognition as both a prognostic and predictive factor for SN metastasis, particularly since the best method for calculating this rate was established.8–11 Nonetheless, in the latest version of the Cancer Staging Manual of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), mitotic rate is recognized only as a prognostic factor in thin melanomas.1

When taking decisions in medicine, it is important to consider evidence based on sound methods to resolve problems that arise when classifying or stratifying patients or assessing prognosis.12 Decision trees are being increasingly used for this purpose, and one particularly useful tool is classification and regression tree (CART) analysis.13 CART offers several advantages over logistic regression. It is simpler to use and interpret, and furthermore, the fact that it is based on a nonparametric method means that no prior assumptions need to be made regarding the distribution of predictors, the relationships between predictors and outcome, or interactions between predictors.

The main aim of this study was to identify predictors of SN metastasis in cutaneous melanoma using CART and logistic regression. A secondary goal was to evaluate the role of these factors in predicting disease-free survival and melanoma-specific survival.

Material and MethodsThis was a retrospective, observational study.

Study PopulationThe study participants were selected from the melanoma databases at Hospital Virgen de la Victoria (HVV) in Malaga, Spain and Instituto Valenciano de Oncología (IVO) in Valencia, Spain. All ethical requirements regarding the use of databases were complied with. The 2 databases have been described in detail in previous studies.14–16

For this particular study, we selected all patients with a single cutaneous melanoma, classified as clinical stage I or II, who had undergone SN biopsy and been prospectively included in the IVO database between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2012 or in the HVV database between October 1, 2001 and December 31, 2012. Patients without an identifiable SN during the SN biopsy were excluded from the study.

The study was approved by the ethics committees at the HVV and IVO.

The dependent variable was SN status, which was classified as positive in the presence of melanoma cells in the SN and negative otherwise.

SN StatusThe methods used for the pathologic examination of the SN are quite similar in both hospitals and are summarized below:

HVV. The first step is the gross identification and retrieval of the SN, with clearing of surrounding fat where necessary. The SN is then fixed in formalin 10% prior to embedding in a paraffin block. Each block is serially sectioned into 3 slices every 250μm until the whole block is cut. The first and last sections are used for hematoxylin-eosin staining, while the middle section is used for immunohistochemical staining with HMB-45.

IVO. The first stage is the same as at the HVV: identification and retrieval of the SN and clearing of fat where necessary. The specimen is also immersed in formalin 10% and embedded in a paraffin block. Serial sections are taken from the entire block every 250μm. Three cross-sections are taken from each section. One is stained with hematoxylin-eosin, and the other 2 are kept for immunohistochemical staining with S-100 protein and HMB-45. The immunohistochemical study is only performed following confirmation of the absence of metastasis in the hematoxylin-eosin section.

Independent VariablesThe following clinical and histologic characteristics were selected as independent variables:

Clinical characteristics. Patient sex and age (≤65 vs >65 years) and anatomic location of the primary melanoma. Anatomic location was dichotomized into axial (head, neck, trunk, and volar or subungual sites) and extremities. The system proposed by Kruper et al.8 was used to classify volar and subungual melanomas, as these are associated with a worse prognosis (possibly partly due to genetic alterations) that distinguishes them from other types of melanoma.17

Histologic characteristics. Breslow thickness (categorized according to the AJCC as ≤1.00, 1.01-2, 2.01-4, and >4mm), ulceration (present vs absent), regression (present vs absent), mitotic rate (0, 1-5, or ≥6 mitoses/mm2),10 and tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) (absent, nonbrisk, and brisk).18

Statistical AnalysisThe dependent variable was SN positivity. Independent variables were included as binary variables (sex, age, ulceration, anatomic location, and regression) or categorical variables (Breslow thickness, TILs, and mitotic rate).

In the logistic regression analysis, we first analyzed the association between SN positivity and the study variables using the χ2 test or univariate logistic regression analysis. The Wald test was used to calculate odds ratios with 95% CIs for all variables. Multiple logistic regression was used to identify independent predictors of SN positivity. All possible interactions between variables were also analyzed. Goodness of fit was assessed with the Hosmer-Lemeshow test.

The classification tree was built using the CART method,19 which is used to build decision trees through a set of rules governing decisions taken to assign an output value to each alternative through a process known as binary recursive partitioning. Each parent note is split into 2 homogeneous child nodes by asking questions with a yes and no answer. The CART process involves several stages: a) tree growing; b) application of stopping rules for the tree-growing process (a maximal tree that overadjusts the data used to generate the tree is built); c) pruning to create a simpler tree containing only the most important nodes; and d) selection of tree with the best generalization ability.20

We used the CART tree-growing process in SPSS version 20.0, with analysis of sensitivity based on the Gini criterion20 and the cross-validation system. In the final tree, each group had at least 20 cases (10 for subgroup analyses).

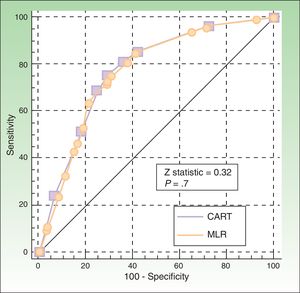

MedCalc statistical software (version 14.8.1) was used to generate receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the CART and logistic regression models and to calculate the respective areas under the curve. The curves were compared using the DeLong method.21

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to evaluate disease-free survival (DFS) and melanoma-specific survival (MSS), and the log rank rest was applied to compare groups in the univariate analysis. The Cox proportional hazards model was used for the multivariate analysis. A P value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. SSPS 20.0 was used for statistical analyses.

ResultsParticipantsIn total, 855 patients met the histologic criteria, provided informed consent, and underwent SNB. The SN was identified in 818 patients (95.6%). Of these 818 patients included in the analysis, 434 (53.1%) were women and 384 (46.9%) were men, with a median age of 53 years (interquartile range, 43-66 years). Table 1 summarizes the clinical and histologic characteristics of the study population stratified by SN status.

Clinical and Histologic Characteristics of 818 Patients According to SNB Result.

| Variable | No. (%) of Patients With Negative SNB | No. (%) of Patients With Positive SNB | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| ≤65 | 479 (75) | 130 (74.3) | NS |

| >65 | 160 (25) | 45 (25.7) | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 330 (51.5) | 104 (58.8) | NS |

| Male | 311 (48.5) | 73 (41.2) | |

| Anatomic Location | |||

| Axial | 136 (21.4) | 30 (16.9) | NS |

| Extremities | 501 (78.6) | 147 (83.1) | |

| Breslow thickness, mm | |||

| ≤1 | 184 (29) | 11 (6.2) | <.001 |

| 1.01-2 | 254 (40.1) | 41 (23.2) | |

| 2.01-4 | 119 (18.8) | 70 (39.5) | |

| >4 | 77 (12.1) | 55 (31.1) | |

| Ulceration | |||

| Present | 145 (23.2) | 85 (48.9) | <.001 |

| Absent | 479 (76.8) | 89 (51.1) | |

| Regression | |||

| Present | 91 (15.8) | 13 (8.3) | .01 |

| Absent | 486 (84.2) | 144 (91.7) | |

| Mitotic rate, No. of mitoses/mm2 | |||

| 0 | 80 (17.4) | 7 (5.3) | <.001 |

| 1-5 | 305 (66.4) | 76 (57.6) | |

| ≥6 | 54 (16.2) | 49 (37.1) | |

| Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes | |||

| Brisk | 41 (8.1) | 4 (3) | 0.057 |

| Nonbrisk | 208 (41.4) | 51 (38) | |

| Absent | 254 (50.5) | 79 (59) | |

Abbreviations: NS, not significant; SNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

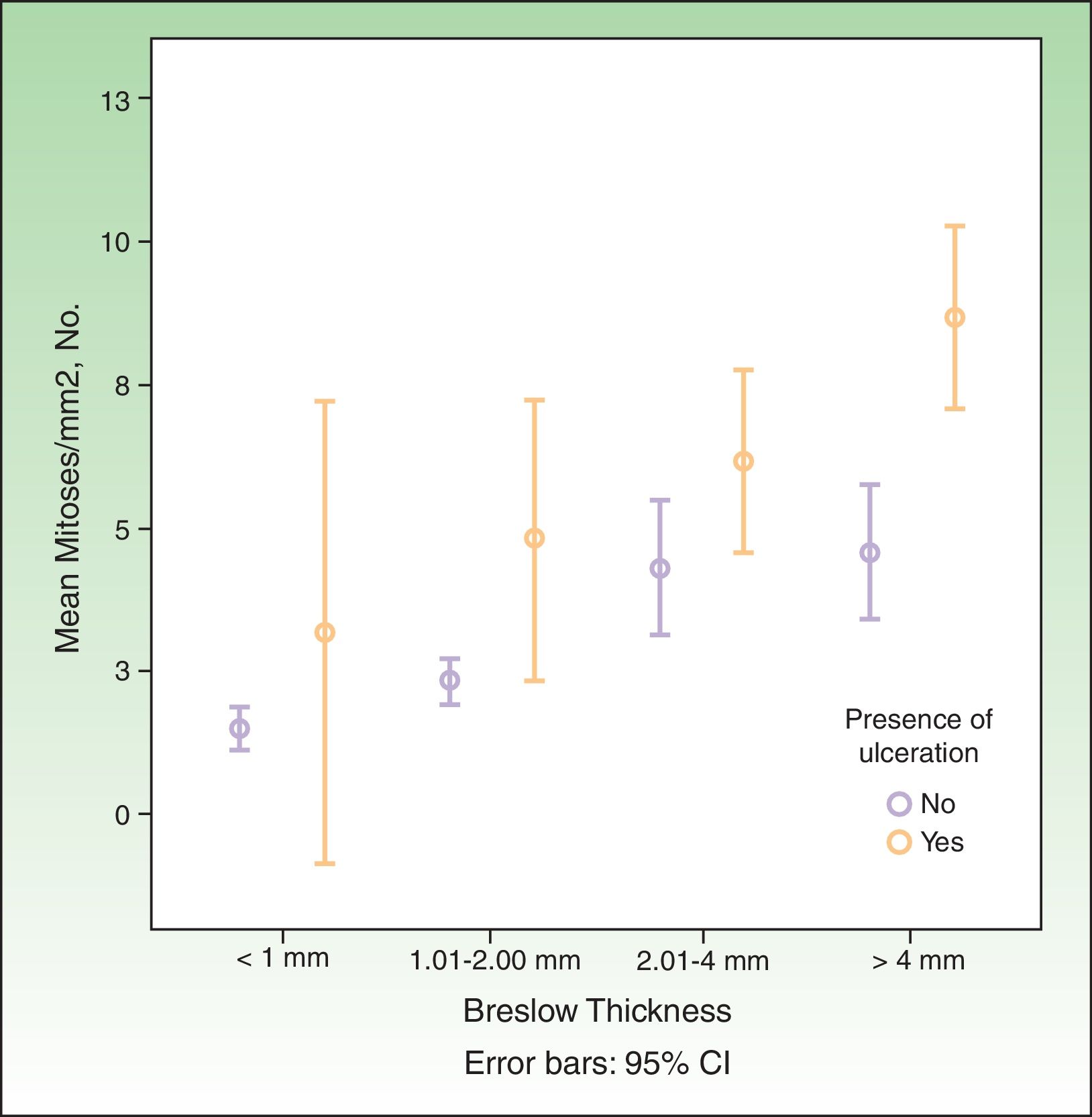

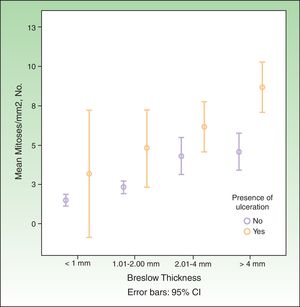

SN metastasis was associated with increased Breslow thickness, presence of ulceration, absence of regression, a high mitotic rate, and absence of TILs. It was not associated with sex, age, or anatomic location. The association between mitotic rate, increased Breslow thickness, and presence of ulceration is shown graphically in Fig. 1.

SN StatusThe following variables were associated with SN metastasis in the univariate analysis: Breslow thickness, presence of ulceration, absence of regression, high mitotic rate, and absence of TILs (Table 2). In the multiple logistic regression model, only ulceration, Breslow thickness, and high mitotic rate (≥6 mitoses/mm2) were independently associated with SN metastasis.

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of Predictors of Positive Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy Result in 818 Patients With Localized Cutaneous Melanoma.

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable | P Value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

| Age, y | ||||

| ≤65 | 1 | … | … | |

| >65 | NS | 1.1 (0,6-1,5) | … | … |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 1 | … | … | |

| Male | NS | 1.3 (0.9-1.9) | … | … |

| Anatomic location | ||||

| Axial | NS | 0.7 (0.5-1.2) | … | … |

| Extremities | 1 | … | … | |

| Breslow thickness, mm | ||||

| ≤1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1.01-2 | .005 | 2.7 (1.1-4.9) | .029 | 18 (1.4-240) |

| 2.01-4 | <.001 | 9.8 (3.9-16.5) | .001 | 66.2 (5.3-830) |

| >4 | <.001 | 12.4 (6-26) | <.001 | 247.7 (17.4-35.34) |

| Ulceration | ||||

| Present | <.001 | 3.2 (2.1-4.7) | .003 | 12.3 (2.3-65) |

| Absent | 1 | 1 | ||

| Regression | ||||

| Present | .01 | 2.1 (1.1-3.8) | … | … |

| Absent | 1 | … | … | |

| Mitotic rate, No. of mitoses/mm2 | ||||

| 0 | 1 | … | … | |

| 1-5 | .01 | 2.8 (1.2-6.3) | … | … |

| ≥6 | <.001 | 7.5 (3.2-17.5) | .046 | 2.6 (1.1-6.6) |

| Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes | ||||

| Brisk | 1 | |||

| Nonbrisk | NS | 2.5(0.8-7.3) | … | … |

| Absent | .03 | 3.2 (1.1-9.2) | … | … |

| Breslow thickness, mm*ulceration | ||||

| 1.01-2* ulceration | .06 | 0.16 (0.02-1.05) | ||

| 2.01-4* ulceration | .03 | 0.15 (0.02-0.9) | ||

| >4* ulceration | .005 | 0.07 (0.01-0.5) | ||

Abbreviations: NS, not significant.

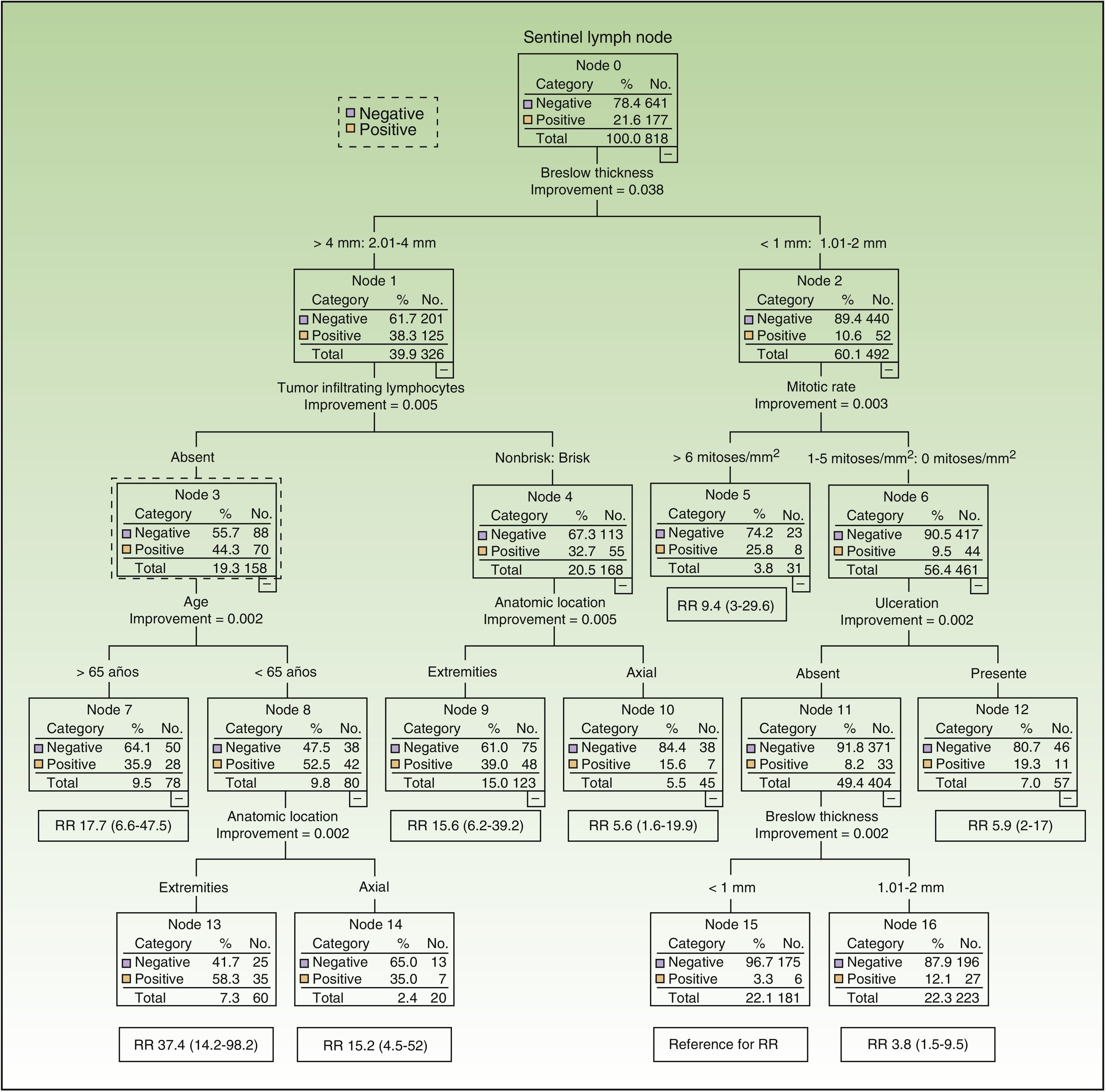

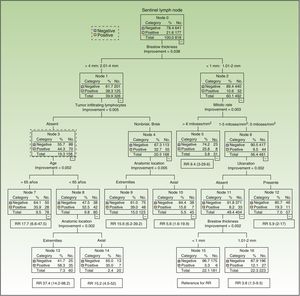

Six of the 8 variables included initially in the CART analysis were used. Breslow thickness (>2mm vs all other thicknesses) was the most important factor. The variables used for melanomas with a thickness of over 2mm were, by order of importance, inflammatory infiltrate (absent vs brisk/nonbrisk), age, and anatomic location. For thinner melanomas, they were, also in order of importance, mitotic rate (≤6 vs <6 mitoses/mm2), ulceration, and Breslow thickness (Fig. 2). Accordingly, patients with the greatest risk of SN involvement were those aged 65 years or younger with melanomas thicker than 2mm located on the extremities, without TILs (SN positivity 58%, n=60). By contrast, patients with the least risk of SN involvement were those with ulcerated melanomas with a Breslow thickness of 1mm or less and a mitotic rate of under 6 mitoses/mm2 (SN positivity 3.3%, n=181).

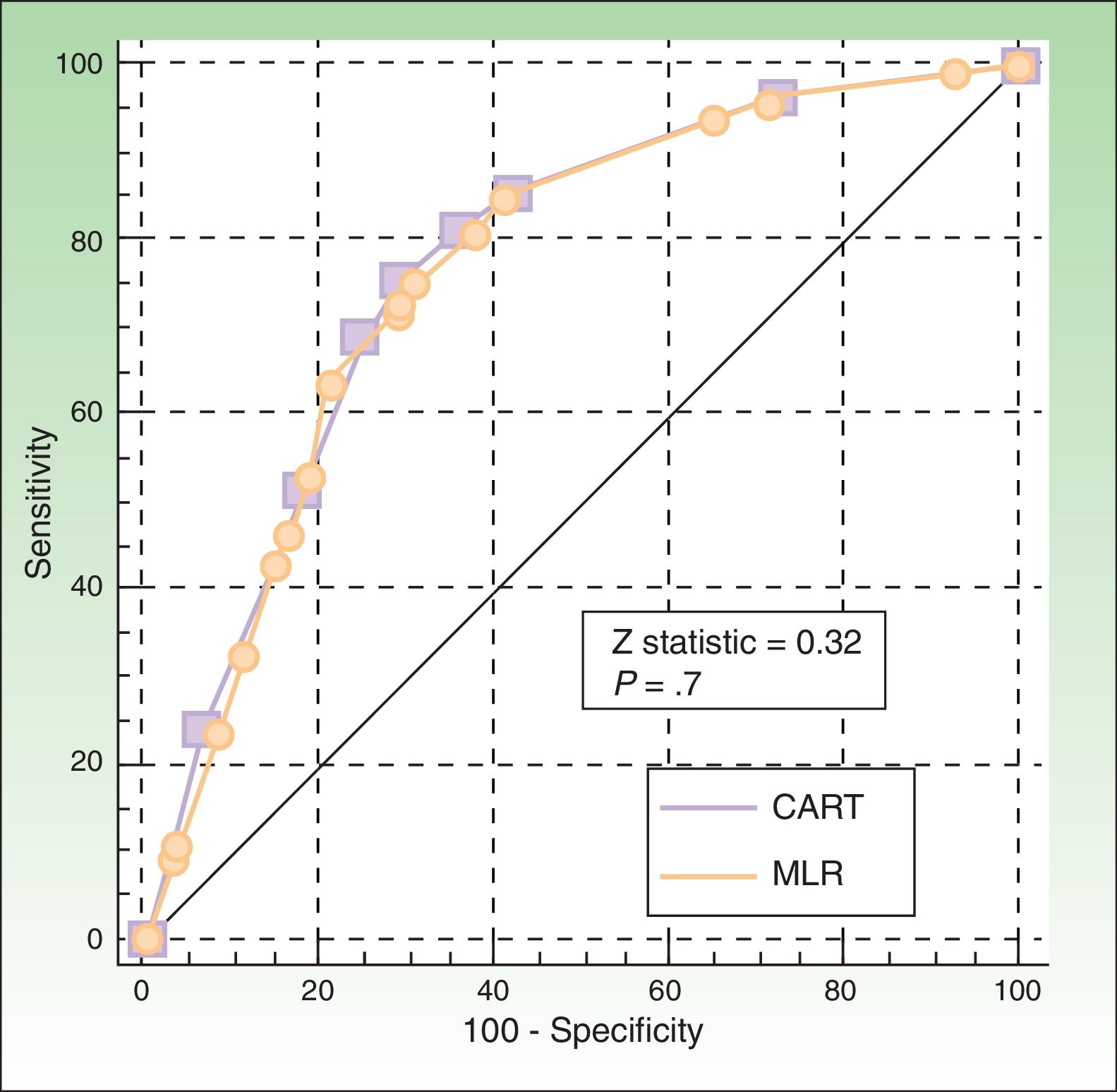

The ROC curves for the CART and logistic regression models were similar (P=.7), with an area under the curve of 0.77 (95% CI, 0.73-0.81) and 0.78 (0.74-0.82), respectively (Fig. 3).

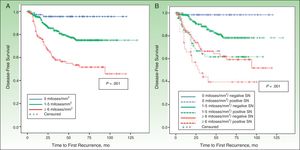

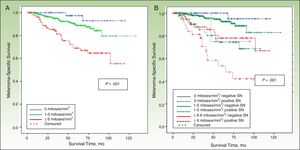

DFS and MSSIn a median follow-up period of 58 months (range, 1-157 months), 104 patients died of melanoma and 172 experienced some form of recurrence (uncensured data in the Cox proportional hazards model). The most important predictor of both DFS and MSS was SN metastasis.

MSS was 68.1% for patients with SN involvement and 93.1% for those without. The Cox proportional hazards model was adjusted for significant variables in the univariate analysis. SN metastasis was the most important prognostic factor for both DFS (hazard ratio, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.5-3.6) and MSS (hazard ratio, 3.5; 95% CI, 1.9-6.3).

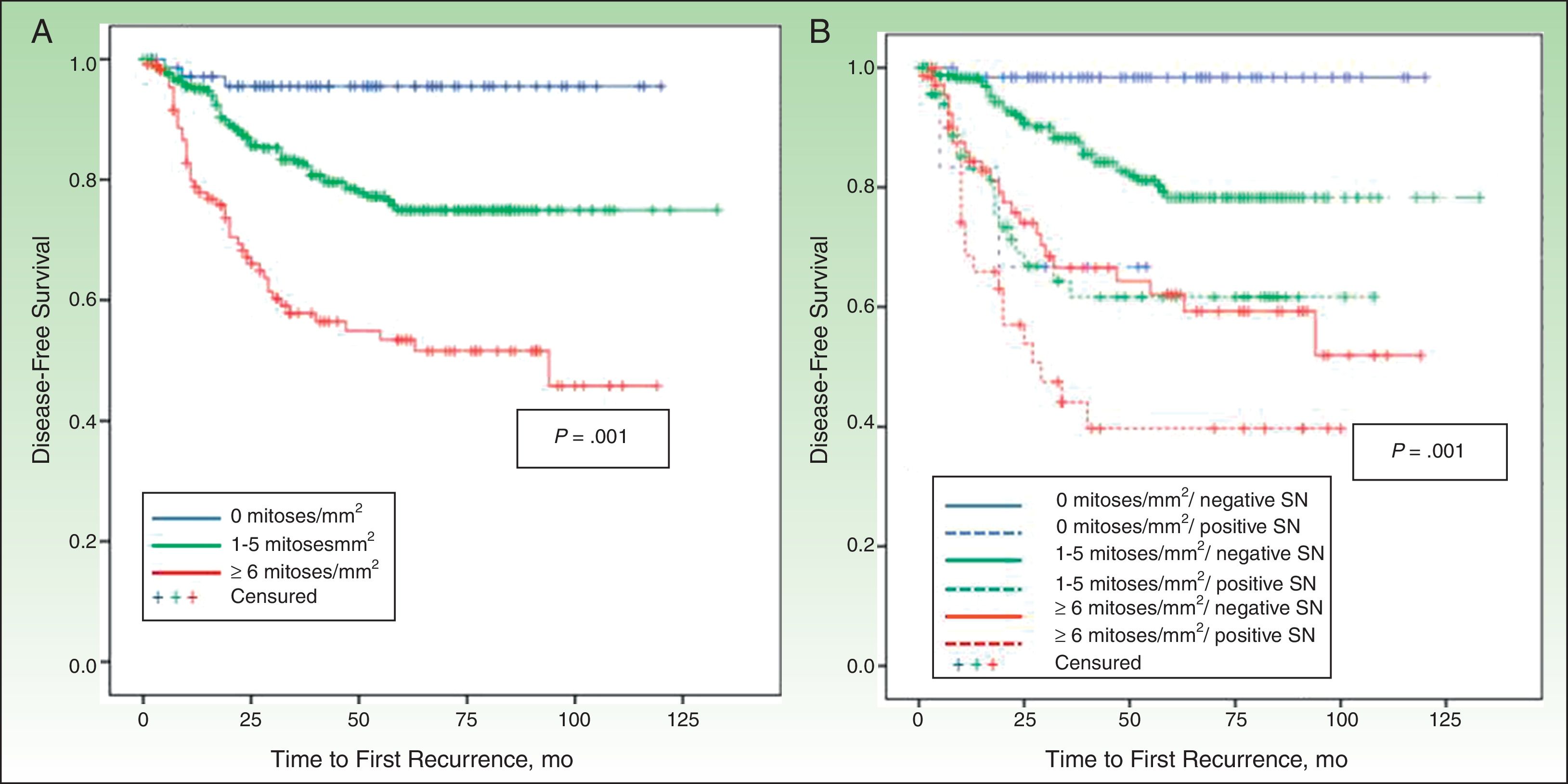

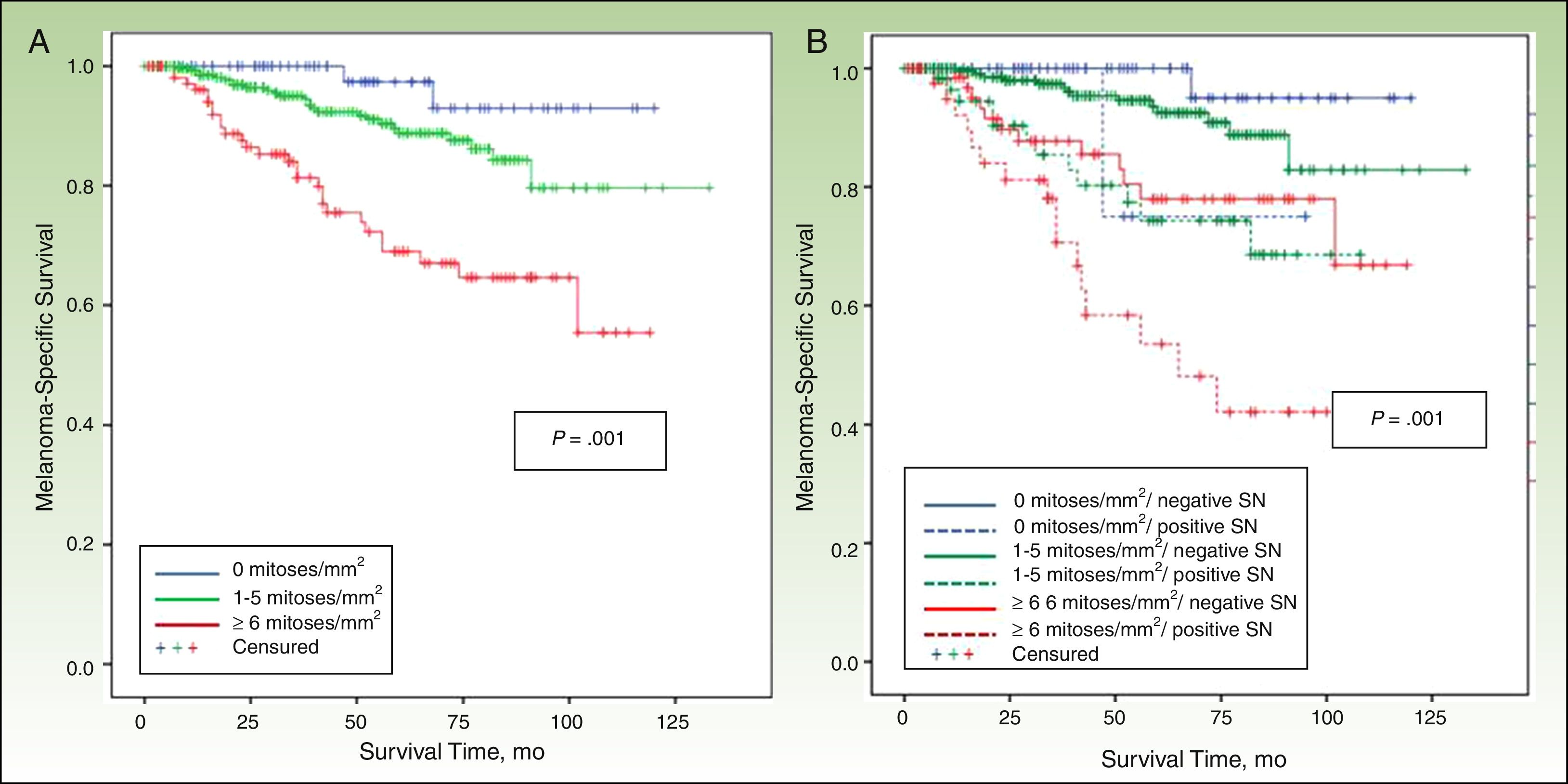

Other significant predictors of DFS (shown in detail in Table 3) were Breslow thickness, age, anatomic location, and mitotic rate (Fig. 4). In the case of MSS (Table 4), mitotic rate was an independent prognostic factor, together with age, anatomic location, and Breslow thickness (Fig. 5).

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis for Disease-Free Survival in 818 Patients With Cutaneous Melanoma.

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable | P Value | Proportional Hazard (95% CI) | P Value | Proportional Hazard (95% CI) |

| Age. y | ||||

| ≤65 | 1 | … | 1 | |

| >65 | .001 | 1.5 (1.1-2.2) | .032 | 1.5 (1.1-2.2) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 0.8 (0.6-1.1) | … | … | |

| Male | NS | 1 | … | … |

| Anatomic location | ||||

| Axial | <.001 | 1.5 (1.2-1.8) | .001 | 1.4 (1.2-1.7) |

| Extremities | 1 | … | 1 | |

| Breslow thickness. mm | ||||

| ≤1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1.01-2 | .01 | 3.2 (1.3-7.7) | .006 | 5.1 (1.2-22) |

| 2.01-4 | <.001 | 9.9 (4.2-23.1) | <.001 | 10.4 (2.4-44.1) |

| >4 | <.001 | 15.4 (6.6-36.1)) | <.001 | 9.5 (2.2-41.7) |

| Ulceration | ||||

| Present | <.001 | 3.6 (2.6-5.2) | … | … |

| Absent | 1 | … | … | |

| Regression | ||||

| Present | 1 | … | … | |

| Absent | .007 | 2.3 (1.3-4.3) | … | … |

| Mitotic rate. No. of mitoses/mm2 | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1-5 | .007 | 4.9 (1.5-15.6) | … | … |

| ≥6 | <.001 | 12.5 (3.9-40.2) | .03 | 2.7 (1.1-6.7) |

| Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes | ||||

| Brisk | 1 | |||

| Nonbrisk | NS | 1.7 (0.7-4) | … | … |

| Absent | NS | 1.8 (0.8-4) | … | … |

| SNB result | ||||

| Positive | <.001 | 3.5 (2.5-5) | .001 | 2.3 (1.5-3.6) |

| Negative | 1 | 1 | ||

Abbreviations: NS, not significant; SNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis for Melanoma-Specific Survival in 818 Patients With Cutaneous Melanoma.

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variable | P Value | Proportional Hazard (95% CI) | P Value | Proportional Hazard (95% CI) |

| Age, y | ||||

| ≤65 | 1 | 1 | ||

| >65 | <.001 | 2.2 (1.3-3.4) | <.001 | 2.9 (1.6-5.1) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 1 | … | … | |

| Male | NS | 0.7 (0.6-1.5) | … | … |

| Tumor site | ||||

| Axial | <.001 | 1.5 (1.2-1.8) | 2.6 (1.6-4.4) | |

| Extremities | 1 | <.001 | 1 | |

| Breslow thickness, mm | ||||

| ≤1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1.01-2 | .027 | 3.5(1.1-12) | … | … |

| 2.01-4 | <.001 | 9.9 (4.2-37.7) | .039 | 4.9 (1.1-21.8) |

| >4 | <.001 | 15.1 (4.5-50) | .024 | 5.8 (1.3-26) |

| Ulceration | ||||

| Present | <.001 | 3.5 (2.2-5.6) | … | … |

| Absent | 1 | … | … | |

| Regression | ||||

| Present | NS | 1 | … | … |

| Absent | 1.5 (0.8-3) | … | … | |

| Mitotic rate, No. of mitoses/mm2 | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1-5 | .032 | 4.8 (1.2-17.8) | .029 | 4.2 (0.9-18.7) |

| ≥6 | <.001 | 14.3 (3.5-59) | .004 | 9.1 (2.1-41.6) |

| Inflammatory infiltrate | ||||

| Brisk | 1 | |||

| Nonbrisk | NS | 1.2 (0.5-4) | … | … |

| Absent | NS | 1.5 (0.4-3.3) | … | … |

| SNB result | ||||

| Positive | <.001 | 4.6 (2.9-7.3) | <.001 | 3.5 (1.9-6.3) |

| Negative | 1 | 1 | ||

Abbreviations: SNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy; NS, not significant.

We have shown in a series of 818 patients with melanoma that mitotic rate, in addition to Breslow thickness and presence of ulceration, is a significant predictor of SN metastasis. Furthermore, mitotic rate was found to be an independent predictor of survival.

Mitotic rate has not been consistently observed to predict SN metastasis in melanoma, unlike ulceration and, even more so, Breslow thickness.14

In our series, a mitotic rate of 6 mitoses/mm2 or more was predictive in the logistic regression model. In the CART analysis, mitotic rate, split into ≥6 mitoses/mm2 versus all other rates, was the most important factor after Breslow thickness, but only in tumors 2mm or thinner.

Different classifications and models can be built using the same variables. CART, however, is much more intuitive and offers easier-to-interpret results than logistic regression, as it can identify predictors that exert different influences on specific groups of patients.20 It is not, however a question of choosing one model or the other, as different methods should be employed to find an optimal solution for any given problem.22

Breslow thickness is considered the most important predictor of SN metastasis.23 In our series, we used a cutoff of 2mm in the CART analysis, as this thickness appears to best value for differentiating between different risks of lymph node metastasis.24

Ulceration has also been highlighted as an important predictor in several studies.14 In our series, it was an independent predictor of SN involvement, but in the CART model it was relevant only for melanomas with a thickness of 2mm or less and a mitotic rate of under 6 mitoses/mm2.

The results of the CART analysis suggest that neither mitotic rate nor presence of ulceration can predict an increased risk of SN involvement in patients with melanomas with a thickness of over 2mm. Absence of TILs, by contrast, was associated with a greater likelihood of SN metastasis. Taylor et al.7 were the first authors to describe a significant association between absence of TILs and presence of regional metastasis. Like us, they found no differences in survival with respect to inflammatory infiltrate. They did find that patients without TILs had a higher frequency of regional lymph node recurrence, but the same patients had a similar frequency of distant recurrences to patients with TILs, offering at least a partial explanation for this discrepancy.

Patient age and anatomic location were also among the deeper nodes in the CART model, but they were not statistically significant in the logistic regression analysis.

Compared with melanomas on the extremities, axial melanomas were associated with a lower relative risk of SN involvement in patients with thick tumors or thin tumors (≤2mm) with ulceration. Axial location, however, has been associated with worse DSF and overall survival in some studies. This observation, which has been corroborated by other authors, is intriguing.25 One explanation is that the increased vascularization in axial tumors, and particularly those located on the head and neck, would result in an increased likelihood of hematogenous metastasis. Alternatively, it is possible that the complexity of the lymph system at this level would make it difficult to identify affected SNs.26

For thick melanomas located on the extremities, we also found that an age of 65 years or younger was associated with greater SN involvement, and paradoxically, better survival.

In the case of melanomas measuring 1mm or less, the frequency of SN involvement was 5.6%, but this dropped to 3.3% in the absence of ulceration and a mitotic rate of under 6 mitoses/mm2. Venna et al.27 reviewed a large body of literature aimed at identifying subgroups of patients with thin melanomas and an increased risk of SN involvement and worse prognosis. More recent studies have identified ulceration as an important predictor in this setting,28,29 but the predictors that are most commonly associated with SN involvement in thin melanomas are Breslow thickness, mitotic rate, Clark level, and absence of TILs. Other, less frequently reported factors are age, sex, vertical growth phase, and lymphovascular invasion.27

In our series, mitotic rate, after SN involvement and Breslow thickness, proved to be an important prognostic factor in both DFS and MSS. This finding is consistent with reports by Azzola et al.,10 whose group in a recent study including more cases confirmed that mitotic rate was a clearly more powerful prognostic indicator than ulceration in primary cutaneous melanoma.30

In conclusion, mitotic rate was associated with a higher frequency of SN involvement in melanomas with a thickness of 2mm or less, although its most important role was as a predictor of survival in this group. After regional lymph node involvement and Breslow thickness, it was the most important prognostic factor, ahead even of ulceration. Finally, inflammatory infiltrate was a predictor of SN metastasis in patients with melanomas measuring over 2mm, but it had no role as a prognostic factor in these patients.

The practical implications of this study are that CART analysis offers a practical and intuitive method for predicting SN metastasis in melanoma and may contribute to improved clinical management in these patients and guide decisions regarding inclusion in clinical trials.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of humans and animalsThe authors declare that no tests were carried out in humans or animals for the purpose of this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed their hospital's protocol on the publication of data concerning patients.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no private patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Tejera-Vaquerizo A, Martín-Cuevas P, Gallego E, Herrera-Acosta E, Traves V, Herrera-Ceballos E, et al. Factores predictivos del estado del ganglio centinela en el melanoma cutáneo: análisis mediante un árbol de clasificación y regresión. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:208–218.