The first evidence of radioactivity was detected by Henri Becquerel. After Marie and Pierre Curie later discovered the first radioactive element, radium, all 3 received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903.1

Although radioactivity has led to great advances in medicine — in our own specialty alone, for example, it has enabled the treatment of certain skin cancers — adequate protection against rays must be provided if adverse effects are to be avoided.2

Modern societies seem to fully grasp the need for protection against the harmful effects of radiation, but that was not the case in the years immediately following the discoveries of Becquerel and the Curies.

ObjectiveThis article aims to illustrate the lack of understanding of radioactivity’s dangers in the early years. To that end, we recount two stories that reveal the consequences of societal ignorance of health threats coupled with an unscrupulous rush to profit from the use of radioactive elements in products sold in the first third of the 20th century.

CommentThe first story unfolded at the beginning of the century, when several companies began to manufacture watches with luminous dials that were highly useful for combatants in World War I. Luminescence was achieved by applying radium paint, but since workers would first lick the bristles of their brushes to point them, they absorbed small amounts of radium each time. After about 5 years on average, some of the workers began to suffer nontraumatic bone fractures and highly aggressive sarcomas on various parts of their bodies. That these adverse events were caused by the radioactive material in radium paint was finally demonstrated only after considerable study.3

The second story involves the use of radium in many products, but mainly cosmetics used during the 1930s. This application was based on the supposed curative properties of radioactive elements and their purported ability to lend a luminescent quality to skin.4,5

Some of the cosmetics companies that used radioactive materials promised their formulations would afford a nearly miraculous “radiant” beauty, a claim supported with falsified data.

Companies such as Tho-Radia, Radior, Artes, and Ramey were created around these products:

- 1

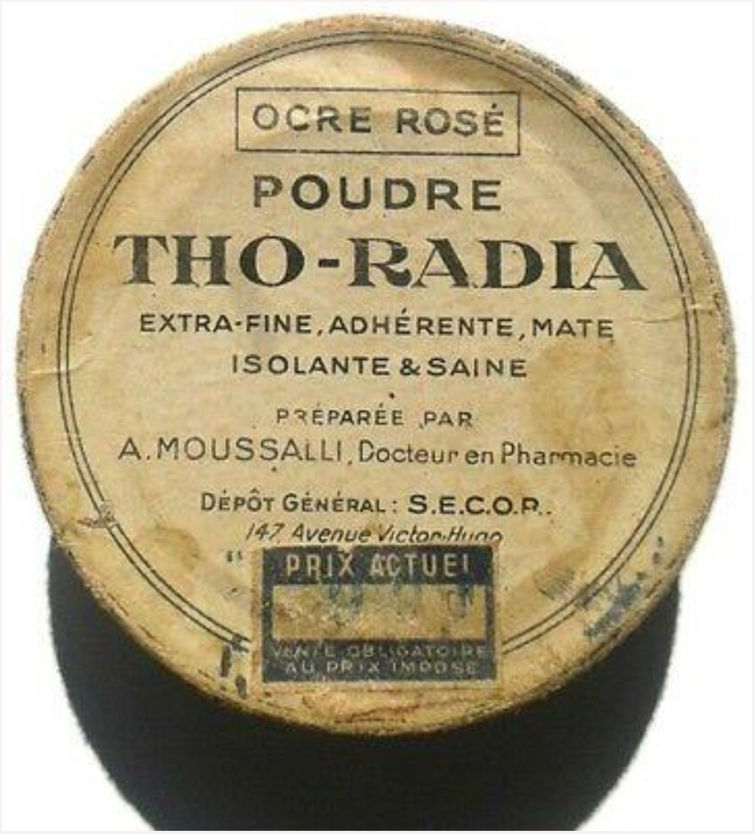

THO-RADIA, the best known manufacturer of the group, was founded in 1932 by Alexis Moussalli, a pharmacist, and Alfred Curie — a doctor who bore no relation to the discoverers of radium in spite of his name.6,7 Their laboratory formulated a range of cosmetics that included lipsticks, creams, powders, toothpastes, and brillantine. Their packaging stated that the products contained radium and thorium (Fig. 1). Even so, the company managed to stay in business until 1962.

Figure 1.Container for a cosmetic powder from the Tho-Radia laboratory. The label emphasizes that the product has excellent cosmetic properties. The word healthy (saine) is used in the description. https://www.picclickimg.com/d/l400/pict/222857405424_/THO-RADIA-POUDRE-exceptionally-rare-French-compact-powder-Ocre.jpg.

(0.1MB). - 2

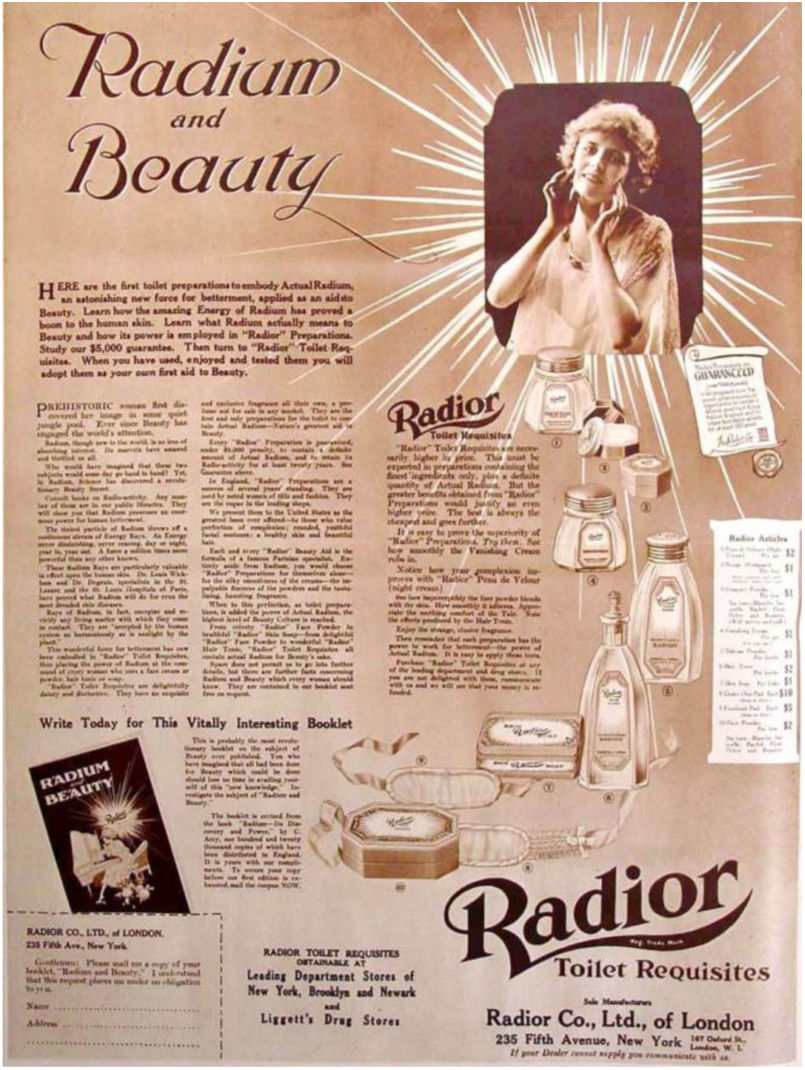

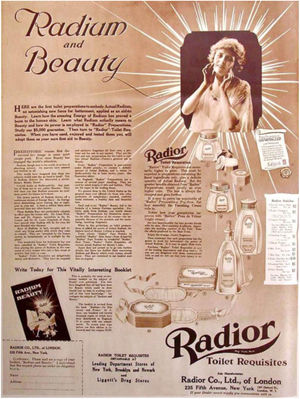

RADIOR was a London enterprise whose advertisements emphasized that users would need no surgical treatments to bring out their beauty (Fig. 2).

- 3

ARTES was another English laboratory that claimed their hydrating cream ensured radiant youth and beauty.

- 4

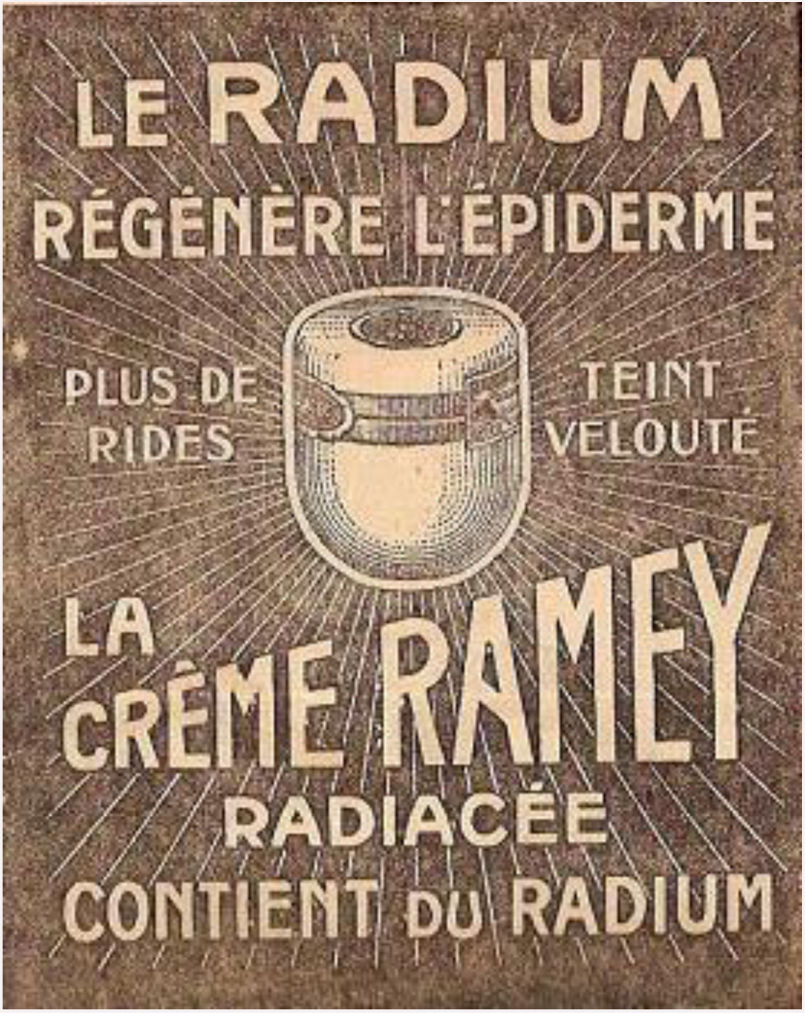

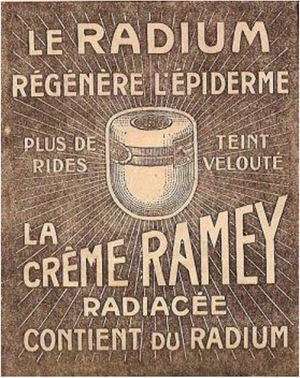

RAMEY was the French manufacturer of a cream that promised an antiaging effect and regeneration of the epidermis (Fig. 3).

We have found no evidence that similar products were manufactured or sold in Spain, but we cannot rule out that some were imported from manufacturers abroad.

Whether the advertised cosmetics truly contained the radioactive ingredients they claimed to have is unknown. Some authors have even questioned the legality of the certificates the manufacturers provided.7

It is also difficult to imagine how the cosmetics industry might have handled radioactive products in an era before today’s safety regulations were in place.8,9

ConclusionsThe story of these products can encourage us to reflect on the lengths our society has gone to in the name of ideal beauty. They also show the importance of laws regulating the manufacture of cosmetics. Regulations have made current manufacturing processes considerably safer than those used in the past.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Díaz Díaz RM, Garrido Gutiérrez C, Maldonado Cid P. Cosméticos radioactivos. La belleza «radiante». Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020;111:863–865.