Skin manifestations associated with chronic kidney disease are very common. Most of these conditions present in the end stages and may affect the patient's quality of life. Knowledge of these entities can contribute to establishing an accurate diagnosis and prognosis. Severe renal pruritus is associated with increased mortality and a poor prognosis. Nail exploration can provide clues about albumin and urea levels. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is a preventable disease associated with gadolinium contrast. Comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus and secondary hyperparathyroidism, can lead to acquired perforating dermatosis and calciphylaxis, respectively. Effective and innovative treatments are available for all of these conditions.

Las manifestaciones cutáneas asociadas a enfermedad renal crónica son muy comunes. La mayoría de estas enfermedades se presentan en la etapa terminal y pueden afectar la calidad de vida del paciente. El conocimiento de estas condiciones puede ser útil para establecer un diagnóstico y pronóstico preciso. El prurito renal severo está asociado a un incremento en la mortalidad y a un pobre pronóstico. La exploración ungueal puede proveer datos acerca del nivel plasmático de albumina y urea. La fibrosis sistémica nefrogénica es una enfermedad prevenible asociada a contrastes con gadolinio. Comorbilidades como la diabetes mellitus y el hiperparatiroidismo secundario, pueden causar dermatosis perforante adquirida y calcifilaxis, respectivamente. Existen tratamientos efectivos e innovadores para todos estos padecimientos.

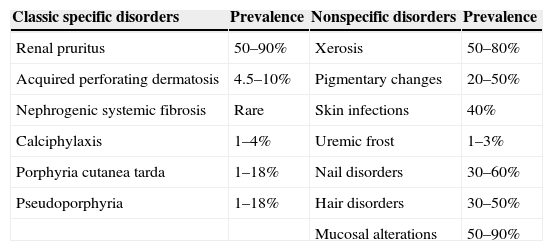

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) commonly exhibit cutaneous manifestations associated with impaired renal function (Table 1). These skin lesions may affect their quality of life, and some conditions could even be life threatening. Knowledge of these lesions is important for an accurate diagnosis and prognosis. This review focuses mainly on classic specific disorders associated with CKD (Table 2), but other common nonspecific conditions are also discussed.

Classification of skin manifestations of chronic kidney disease and prevalence.

| Classic specific disorders | Prevalence | Nonspecific disorders | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Renal pruritus | 50–90% | Xerosis | 50–80% |

| Acquired perforating dermatosis | 4.5–10% | Pigmentary changes | 20–50% |

| Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis | Rare | Skin infections | 40% |

| Calciphylaxis | 1–4% | Uremic frost | 1–3% |

| Porphyria cutanea tarda | 1–18% | Nail disorders | 30–60% |

| Pseudoporphyria | 1–18% | Hair disorders | 30–50% |

| Mucosal alterations | 50–90% |

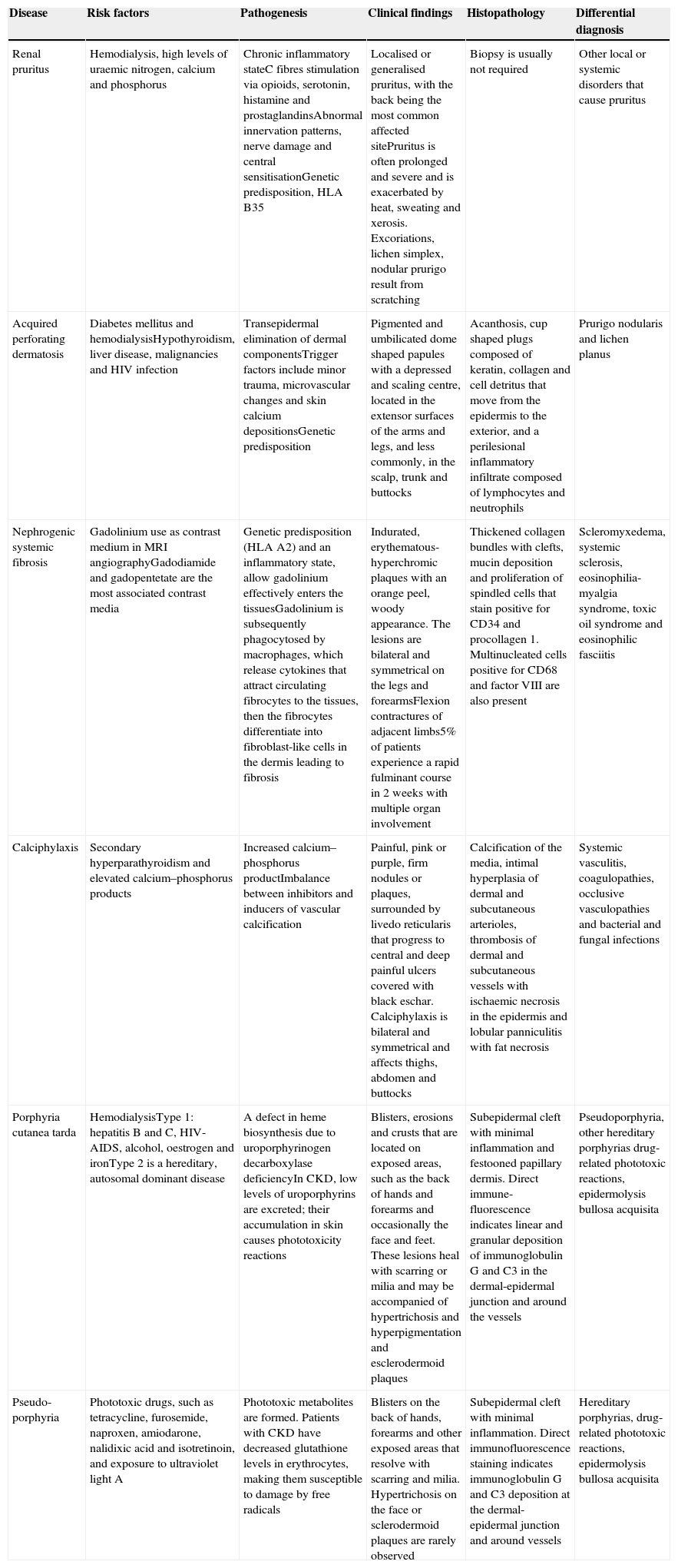

Summary of classic specific disorders.

| Disease | Risk factors | Pathogenesis | Clinical findings | Histopathology | Differential diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Renal pruritus | Hemodialysis, high levels of uraemic nitrogen, calcium and phosphorus | Chronic inflammatory stateC fibres stimulation via opioids, serotonin, histamine and prostaglandinsAbnormal innervation patterns, nerve damage and central sensitisationGenetic predisposition, HLA B35 | Localised or generalised pruritus, with the back being the most common affected sitePruritus is often prolonged and severe and is exacerbated by heat, sweating and xerosis. Excoriations, lichen simplex, nodular prurigo result from scratching | Biopsy is usually not required | Other local or systemic disorders that cause pruritus |

| Acquired perforating dermatosis | Diabetes mellitus and hemodialysisHypothyroidism, liver disease, malignancies and HIV infection | Transepidermal elimination of dermal componentsTrigger factors include minor trauma, microvascular changes and skin calcium depositionsGenetic predisposition | Pigmented and umbilicated dome shaped papules with a depressed and scaling centre, located in the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs, and less commonly, in the scalp, trunk and buttocks | Acanthosis, cup shaped plugs composed of keratin, collagen and cell detritus that move from the epidermis to the exterior, and a perilesional inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and neutrophils | Prurigo nodularis and lichen planus |

| Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis | Gadolinium use as contrast medium in MRI angiographyGadodiamide and gadopentetate are the most associated contrast media | Genetic predisposition (HLA A2) and an inflammatory state, allow gadolinium effectively enters the tissuesGadolinium is subsequently phagocytosed by macrophages, which release cytokines that attract circulating fibrocytes to the tissues, then the fibrocytes differentiate into fibroblast-like cells in the dermis leading to fibrosis | Indurated, erythematous-hyperchromic plaques with an orange peel, woody appearance. The lesions are bilateral and symmetrical on the legs and forearmsFlexion contractures of adjacent limbs5% of patients experience a rapid fulminant course in 2 weeks with multiple organ involvement | Thickened collagen bundles with clefts, mucin deposition and proliferation of spindled cells that stain positive for CD34 and procollagen 1. Multinucleated cells positive for CD68 and factor VIII are also present | Scleromyxedema, systemic sclerosis, eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome, toxic oil syndrome and eosinophilic fasciitis |

| Calciphylaxis | Secondary hyperparathyroidism and elevated calcium–phosphorus products | Increased calcium–phosphorus productImbalance between inhibitors and inducers of vascular calcification | Painful, pink or purple, firm nodules or plaques, surrounded by livedo reticularis that progress to central and deep painful ulcers covered with black eschar. Calciphylaxis is bilateral and symmetrical and affects thighs, abdomen and buttocks | Calcification of the media, intimal hyperplasia of dermal and subcutaneous arterioles, thrombosis of dermal and subcutaneous vessels with ischaemic necrosis in the epidermis and lobular panniculitis with fat necrosis | Systemic vasculitis, coagulopathies, occlusive vasculopathies and bacterial and fungal infections |

| Porphyria cutanea tarda | HemodialysisType 1: hepatitis B and C, HIV-AIDS, alcohol, oestrogen and ironType 2 is a hereditary, autosomal dominant disease | A defect in heme biosynthesis due to uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase deficiencyIn CKD, low levels of uroporphyrins are excreted; their accumulation in skin causes phototoxicity reactions | Blisters, erosions and crusts that are located on exposed areas, such as the back of hands and forearms and occasionally the face and feet. These lesions heal with scarring or milia and may be accompanied of hypertrichosis and hyperpigmentation and esclerodermoid plaques | Subepidermal cleft with minimal inflammation and festooned papillary dermis. Direct immune-fluorescence indicates linear and granular deposition of immunoglobulin G and C3 in the dermal-epidermal junction and around the vessels | Pseudoporphyria, other hereditary porphyrias drug-related phototoxic reactions, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita |

| Pseudo-porphyria | Phototoxic drugs, such as tetracycline, furosemide, naproxen, amiodarone, nalidixic acid and isotretinoin, and exposure to ultraviolet light A | Phototoxic metabolites are formed. Patients with CKD have decreased glutathione levels in erythrocytes, making them susceptible to damage by free radicals | Blisters on the back of hands, forearms and other exposed areas that resolve with scarring and milia. Hypertrichosis on the face or sclerodermoid plaques are rarely observed | Subepidermal cleft with minimal inflammation. Direct immunofluorescence staining indicates immunoglobulin G and C3 deposition at the dermal-epidermal junction and around vessels | Hereditary porphyrias, drug-related phototoxic reactions, epidermolysis bullosa acquisita |

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging, CKD: chronic kidney disease.

Although the pathogenesis is not clear in the majority of cases, effective and innovative treatments are available for these conditions (Table 3).

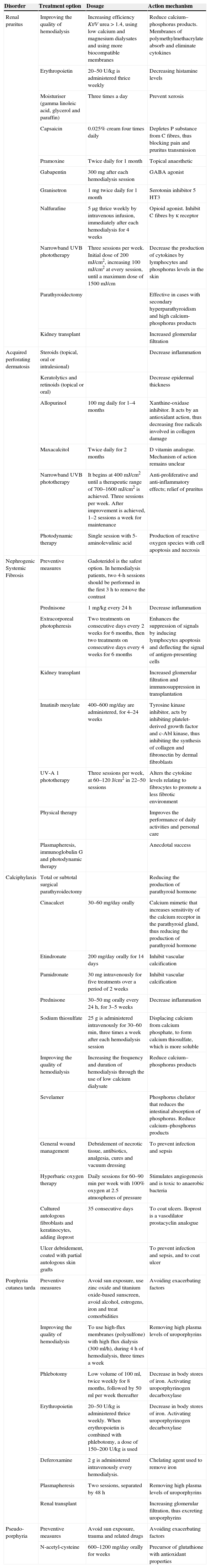

Treatment of classic specific disorders associated to chronic kidney disease.

| Disorder | Treatment option | Dosage | Action mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Renal pruritus | Improving the quality of hemodialysis | Increasing efficiency Kt/V urea>1.4, using low calcium and magnesium dialysates and using more biocompatible membranes | Reduce calcium–phosphorus products. Membranes of polymethylmethacrylate absorb and eliminate cytokines |

| Erythropoietin | 20–50U/kg is administered thrice weekly | Decreasing histamine levels | |

| Moisturiser (gamma linoleic acid, glycerol and paraffin) | Three times a day | Prevent xerosis | |

| Capsaicin | 0.025% cream four times daily | Depletes P substance from C fibres, thus blocking pain and pruritus transmission | |

| Pramoxine | Twice daily for 1 month | Topical anaesthetic | |

| Gabapentin | 300mg after each hemodialysis session | GABA agonist | |

| Granisetron | 1mg twice daily for 1 month | Serotonin inhibitor 5 HT3 | |

| Nalfurafine | 5μg thrice weekly by intravenous infusion, immediately after each hemodialysis for 4 weeks | Opioid agonist. Inhibit C fibres by κ receptor | |

| Narrowband UVB phototherapy | Three sessions per week. Initial dose of 200mJ/cm2, increasing 100mJ/cm2 at every session, until a maximum dose of 1500mJ/cm | Decrease the production of cytokines by lymphocytes and phosphorus levels in the skin | |

| Parathyroidectomy | Effective in cases with secondary hyperparathyroidism and high calcium-phosphorus products | ||

| Kidney transplant | Increased glomerular filtration | ||

| Acquired perforating dermatosis | Steroids (topical, oral or intralesional) | Decrease inflammation | |

| Keratolytics and retinoids (topical or oral) | Decrease epidermal thickness | ||

| Allopurinol | 100mg daily for 1–4 months | Xanthine-oxidase inhibitor. It acts by an antioxidant action, thus decreasing free radicals involved in collagen damage | |

| Maxacalcitol | Twice daily for 2 months | D vitamin analogue. Mechanism of action remains unclear | |

| Narrowband UVB phototherapy | It begins at 400mJ/cm2 until a therapeutic range of 700–1600mJ/cm2 is achieved. Three sessions per week. After improvement is achieved, 1–2 sessions a week for maintenance | Anti-proliferative and anti-inflammatory effects; relief of pruritus | |

| Photodynamic therapy | Single session with 5-aminolevulinic acid | Production of reactive oxygen species with cell apoptosis and necrosis | |

| Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis | Preventive measures | Gadoteridol is the safest option. In hemodialysis patients, two 4-h sessions should be performed in the first 3h to remove the contrast | |

| Prednisone | 1mg/kg every 24h | Decrease inflammation | |

| Extracorporeal photopheresis | Two treatments on consecutive days every 2 weeks for 6 months, then two treatments on consecutive days every 4 weeks for 6 months | Enhances the suppression of signals by inducing lymphocytes apoptosis and deflecting the signal of antigen-presenting cells | |

| Kidney transplant | Increased glomerular filtration and immunosuppression in transplantation | ||

| Imatinib mesylate | 400–600mg/day are administered, for 4–24 weeks | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor, acts by inhibiting platelet-derived growth factor and c-Abl kinase, thus inhibiting the synthesis of collagen and fibronectin by dermal fibroblasts | |

| UV-A 1 phototherapy | Three sessions per week, at 60–120J/cm2 in 22–50 sessions | Alters the cytokine levels relating to fibrocytes to promote a less fibrotic environment | |

| Physical therapy | Improves the performance of daily activities and personal care | ||

| Plasmapheresis, immunoglobulin G and photodynamic therapy | Anecdotal success | ||

| Calciphylaxis | Total or subtotal surgical parathyroidectomy | Reducing the production of parathyroid hormone | |

| Cinacalcet | 30–60mg/day orally | Calcium mimetic that increases sensitivity of the calcium receptor in the parathyroid gland, thus reducing the production of parathyroid hormone | |

| Etindronate | 200mg/day orally for 14 days | Inhibit vascular calcification | |

| Pamidronate | 30mg intravenously for five treatments over a period of 2 weeks | Inhibit vascular calcification | |

| Prednisone | 30–50mg orally every 24h, for 3–5 weeks | Decrease inflammation | |

| Sodium thiosulfate | 25g is administered intravenously for 30–60min, three times a week after each hemodialysis session | Displacing calcium from calcium phosphate, to form calcium thiosulfate, which is more soluble | |

| Improving the quality of hemodialysis | Increasing the frequency and duration of hemodialysis through the use of low calcium dialysate | Reduce calcium–phosphorus products | |

| Sevelamer | Phosphorus chelator that reduces the intestinal absorption of phosphorus. Reduce calcium–phosphorus products | ||

| General wound management | Debridement of necrotic tissue, antibiotics, analgesia, cures and vacuum dressing | To prevent infection and sepsis | |

| Hyperbaric oxygen therapy | Daily sessions for 60–90min per week with 100% oxygen at 2.5 atmospheres of pressure | Stimulates angiogenesis and is toxic to anaerobic bacteria | |

| Cultured autologous fibroblasts and keratinocytes, adding iloprost | 35 consecutive days | To coat ulcers. Iloprost is a vasodilator prostacyclin analogue | |

| Ulcer debridement, coated with partial autologous skin grafts | To prevent infection and sepsis, and to coat ulcer | ||

| Porphyria cutanea tarda | Preventive measures | Avoid sun exposure, use zinc oxide and titanium oxide-based sunscreen, avoid alcohol, estrogens, iron and treat comorbidities | Avoiding exacerbating factors |

| Improving the quality of hemodialysis | To use high-flux membranes (polysulfone) with high flux dialysis (300ml/h), during 4h of hemodialysis, three times a week | Removing high plasma levels of uroporphyrins | |

| Phlebotomy | Low volume of 100ml, twice weekly for 8 months, followed by 50ml per week thereafter | Decrease in body stores of iron. Activating uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase | |

| Erythropoietin | 20–50U/kg is administered thrice weekly. When erythropoietin is combined with phlebotomy, a dose of 150–200U/kg is used | Decrease in body stores of iron. Activating uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase | |

| Deferoxamine | 2g is administered intravenously every hemodialysis. | Chelating agent used to remove iron | |

| Plasmapheresis | Two sessions, separated by 48h | Removing high plasma levels of uroporphyrins | |

| Renal transplant | Increasing glomerular filtration, thus excreting uroporphyrins | ||

| Pseudo-porphyria | Preventive measures | Avoid sun exposure, trauma and related drugs | Avoiding exacerbating factors |

| N-acetyl-cysteine | 600–1200mg/day orally for weeks | Precursor of glutathione with antioxidant properties |

By definition, CKD comprises a structural renal injury (which may be evident in urine, blood, imaging studies or tissue biopsies) or a functional impairment (manifested as a decreased glomerular filtration rate of less than 60ml/min/1.73m2) over a period of 3 months. Most skin manifestations of renal impairment occur in patients with end-stage CKD (stage 5) with a glomerular filtration rate less than 15ml/min/1.73m2.1,2

Renal pruritusRenal pruritus is observed in 50–90% of patients with end-stage CKD, primarily in individuals who have been on hemodialysis.3 The severity rating scales typically used in renal pruritus include the visual analogue scale and the Yospovitch validated questionnaire.4 Pruritus causes anxiety, depression and sleep disorders, and severe pruritus has been described as an independent risk factor for increased mortality and a poor prognosis.5

The cause of renal pruritus is multifactorial. Risk factors such as male sex and high levels of uraemic nitrogen, calcium, phosphorus, β2 microglobulin, magnesium, aluminium, vitamin A, histamine and mast cells, have been reported.6,7

Renal pruritus is considered to be a manifestation of a chronic inflammatory state, which involves cytokines such as TNF, IFN-γ, and IL2 and acute phase reactants such as C-reactive protein. Pruritus is transmitted by C fibres. Opioids stimulate C fibres through μ receptors and inhibit C fibres through κ receptors. C fibre stimulation via serotonin, histamine and prostaglandins might also play an important role. Abnormal innervation patterns, nerve damage and central sensitisation are additional proposed mechanisms. A genetic predisposition particularly associated with HLA B35 has been described.6,7

Clinical manifestations include localised or generalised pruritus, with the back being the most commonly affected site. Pruritus is often prolonged and severe and is exacerbated by heat, sweating and xerosis. Skin lesions, such as excoriations, lichen simplex, nodular prurigo and keratotic papules, may result from scratching (Fig. 1).6,7

In terms of treatment, the main objective is to relieve itching and improve the quality of life. Definitive treatment involves kidney transplantation. It is important to mention that antihistamines are not effective, and the majority of available treatments are only empirical and lack strong evidence.6,7

General treatment consists of improving the quality of haemodialysis, increasing efficiency Kt/V urea>1.4 (Kt/V=dialysis adequacy. K, clearance. t, time. V, volume of distribution) using low calcium and magnesium dialysates, reducing calcium–phosphorus products and using more biocompatible membranes, such as those made of polymethylmethacrylate.8

Erythropoietin efficiently relieves itching by decreasing histamine levels. Its effect is not associated with haemoglobin levels and it is lost when administration is discontinued.9 It is important to avoid xerosis, sweating and heat. Moisturisers constitute the first line of therapy, especially those containing gamma linoleic acid, glycerol and paraffin.10 The addition of endocannabinoids to moisturisers has been proven effective.11

Topical treatment is preferred for localised pruritus. Studies have reported the efficacy of capsaicin and pramoxine. Capsaicin depletes P substance from C fibres, thus blocking pain and pruritus transmission; it is used as 0.025% cream four times daily.12 Pramoxine lotion, a topical anaesthetic, used twice daily for 1 month has been proven effective.13 The use of calcineurin inhibitors is controversial and is not recommended.14,15

Systemic treatment with gabapentin, a GABA agonist, is effective and safe. Due to its renal clearance, gabapentin is administered at low doses of 300mg after each haemodialysis session.16–18 The serotonin inhibitor 5 HT3 granisetron (1mg twice daily for 1 month) is also effective.19,20 The opioid agonist nalfurafine has proven to be effective.21 Phototherapy with narrowband UVB has been used to decrease the production of cytokines by lymphocytes and to reduce phosphorus levels in the skin.22 Among surgical treatments, parathyroidectomy can be effective in cases with secondary hyperparathyroidism and high calcium–phosphorus products.23 However, kidney transplantation is the definitive treatment.

Acquired perforating dermatosis (APD)APD is commonly observed in patients with end-stage CKD, especially in individuals with diabetes mellitus and individuals receiving haemodialysis.24–26

The pathogenesis of APD is unclear. APD is associated with diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, liver disease, malignancies and HIV infection. The mechanism involves transepidermal elimination of dermal components (collagen, elastin and cell detritus). Proposed trigger factors include minor trauma, such as scratching, microvascular changes associated with diabetes mellitus, skin calcium depositions with foreign body inflammatory response and genetic predisposition.24,26

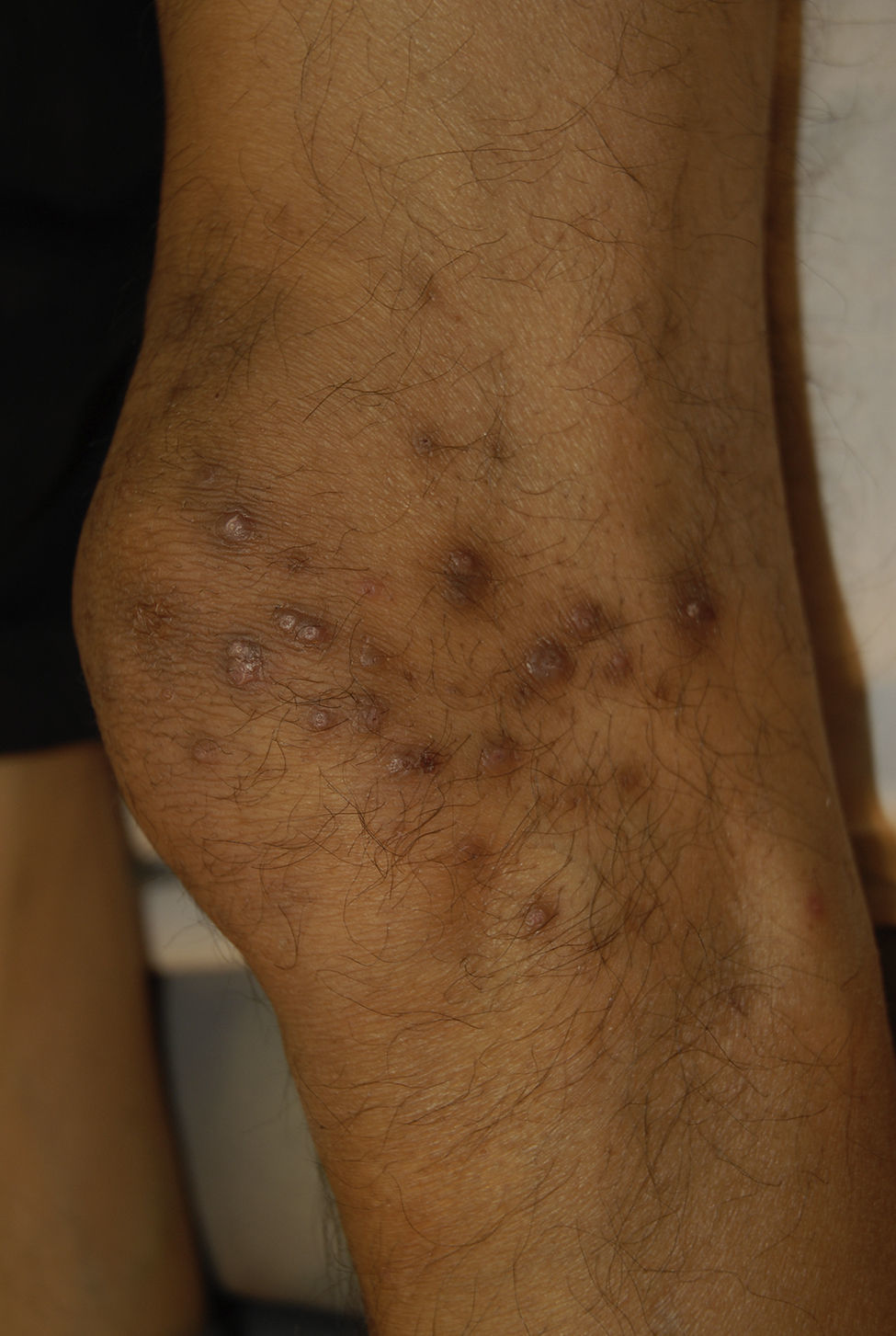

Clinical manifestations include pigmented and umbilicated dome shaped papules with a depressed and scaling centre, located on the extensor surfaces of the arms and legs and less commonly, on the scalp, trunk and buttocks (Fig. 2). Koebner phenomenon may be present. This condition appears in outbreaks and typically resolves in 6–8 weeks with residual pigmentation and scarring. Differential diagnoses include prurigo nodularis and lichen planus.24,26

Histopathology findings include an excavated epidermis, acanthosis, cup shaped plugs composed of keratin, collagen and cell detritus that move from the epidermis to the exterior, and a perilesional inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and neutrophils.24

Steroids (topical, oral or intralesional) are used to decrease inflammation and keratolytics and retinoids (topical or oral) are used to decrease epidermal thickness.27

Allopurinol, a xanthine-oxidase inhibitor, is used at a dose of 100mg daily for 1–4 months; it has been proven effective in a series of cases. Allopurinol is thought to have antioxidant activity, thus decreasing free radicals involved in collagen damage.28 Maxacalcitol (0.0025% ointment), a D vitamin analogue, was reported successful in four treated cases. It is applied twice daily for 2 months. Its mechanism of action remains unclear.29

UVB narrowband phototherapy has been used with success in a series of cases. Benefits are noted in 10–15 weeks.30 Photodynamic therapy has also been reported to be effective.31

Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF)Formerly called nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy, 380 cases of this rare disease have been registered at Yale University, and the first cases were recorded in 1997. No differences in gender and ethnicity were noted. NFS occurs in all ages, but predominantly in middle age.2,32

Ninety-five percent of the cases are associated with gadolinium, a contrast medium, which is used in MRI angiography in patients with low glomerular filtration rates.2,32

Gadodiamide and gadopentetate are the most common causes of contrast media associated with NSF. The poorer the glomerular filtration rate, the longer the half-life of gadolinium. In addition, 73.8% and 92.4% of gadolinium is excreted in a single haemodialysis session or two sessions, respectively, but gadolinium is not properly excreted in peritoneal dialysis.2,32

In patients with a genetic predisposition (HLA A2) or an inflammatory state, a hypercoagulable state or endothelial damage, gadolinium enters the tissues, 35–150-fold more effectively compared with healthy patients. Gadolinium is subsequently phagocytosed by macrophages, which release cytokines that attract circulating fibrocytes (CD34/procollagen I+) to the tissues. Once in the tissue, the fibrocytes differentiate into fibroblast-like cells in the dermis, leading to fibrosis.2,32

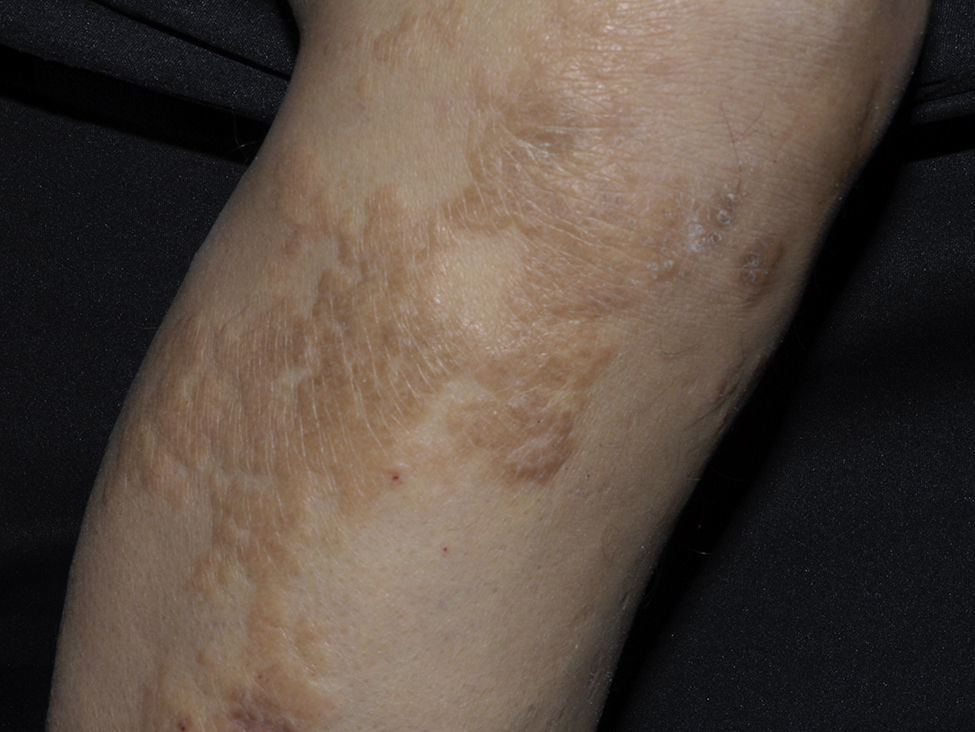

Clinical manifestations include indurated, erythematous-hyperchromic plaques with an orange peel, woody or cobblestone appearance. Nodules and bullae may be present on the hands and feet, or yellowish edematous plaques are noted on the sclera (Fig. 3). The lesions are bilateral and symmetrical on the legs and forearms. The condition is occasionally observed on the trunk and buttocks and generally spares the face.2,32

A burning, itching, and stinging pain occurs. Flexion contractures of adjacent limbs are noted, days to weeks after exposure to the contrast, and the condition tends to be chronic. Remission is achieved in a few cases, leaving atrophic and hypopigmented lesions; 5% of patients experience a rapid fulminant course in 2 weeks with multiple organ involvement (lungs, heart and oesophagus). Differential diagnoses include scleromyxedema, systemic sclerosis, eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome, toxic oil syndrome and eosinophilic fasciitis.2,32

The histopathology is characterised by thickened collagen bundles with clefts, mucin deposition and proliferation of spindled cells that stain positive for CD34 and procollagen 1. Multinucleated cells positive for CD68 and factor VIII are also present.2,24,32

For prevention, if a macrocyclic contrast medium must be used, gadoteridol is the safest option. In haemodialysis patients, two 4-h sessions are required to remove the contrast; these sessions should be performed in the first 3h.33

Most treatments demonstrate efficacy in anecdotal and cases reports. Steroids and immunosuppressants are generally ineffective. Oral prednisone may be used with some efficacy, but many adverse effects are observed.33

Extracorporeal photopheresis is available in a few centres, but is prohibitively expensive. It has been proven to be effective in all patients, increasing softening of injuries and mobility ranges. Extracorporeal photopheresis enhances the suppression of signals by inducing lymphocyte apoptosis and deflecting the signal of antigen-presenting cells.34

Kidney transplantation offers improvement in 54% of patients and full remission has been achieved in some cases. It improves mobility ranges of flexion contracture, likely due to increased glomerular filtration and immunosuppression after transplantation.35,36

Imatinib mesylate, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, acts by inhibiting platelet-derived growth factor and c-Abl kinase, thus inhibiting the synthesis of collagen and fibronectin by dermal fibroblasts. Doses of 400–600mg/day are administered for 4–24 weeks, achieving mild to moderate success. The lesions are softened, but little improvement is noted in the range of motion.37

UV-A 1 phototherapy has been proven effective in smoothing skin lesions, with little improvement in range of motion. It is used at 60–120J/cm2 in 22–50 sessions.38

Plasmapheresis and immunoglobulin G exhibit anecdotal success.39 Physical therapy improves the performance of daily activities and personal care, with little improvement in the range of motion.40 In a case report, photodynamic therapy was effective along with kidney transplantation.41

CalciphylaxisCalciphylaxis occurs in patients with CKD on hemodialysis; it is associated with secondary hyperparathyroidism and elevated calcium-phosphorus products. Calciphylaxis is an obliterative vasculopathy caused by the deposition of calcium in the arterioles of the skin, leading to thrombosis and ischaemic necrosis with ulceration.2

Calciphylaxis is commonly observed in women, in patients with diabetes mellitus, obesity, hypoalbuminemia, liver cirrhosis, those who use warfarin, and those with systemic inflammation and malignancy. Sepsis can cause up to 80% mortality via skin ulcer infection.2

Its ethiopathogenic mechanism is unclear. Predisposition plus a causal factor are necessary. Calcium–phosphorus products are increased in the majority of patients, but this increase is not sufficient alone to cause the condition. An imbalance between inhibitors and inducers of vascular calcification is noted. Osteopontin and bone morphogenic protein 2 serve as inducers, whereas GI protein matrix, fetuin and pyrophosphate act as inhibitors. Aluminium deposition may also be an inductor.2

Clinical manifestations include painful, pink or purple, firm nodules or plaques, surrounded by livedo reticularis that progress to central and deep, painful ulcers covered with black eschar and a reticulated depigmentation in the periphery (Fig. 4). Calciphylaxis is bilateral and symmetrical and affects adipose tissue areas, such as the thighs, abdomen and buttocks.42,43

Histopathologic findings include calcification of the media, intimal hyperplasia of dermal and subcutaneous arterioles, thrombosis of dermal and subcutaneous vessels with ischaemic necrosis in the epidermis and lobular panniculitis with fat necrosis. On radiography, linear calcium deposits are observed. The involvement of small blood vessels (0.5mm) is the most specific sign; however, many patients exhibit vascular calcification without calciphylaxis.42,43

For therapy, early total or subtotal surgical parathyroidectomy increases survival. Cinacalcet is a calcium mimetic that increases sensitivity of the calcium receptor in the parathyroid gland, thus reducing the production of parathyroid hormone. Cinacalcet is used in cases where parathyroidectomy is delayed or contraindicated. Treatment is discontinued once PTH reaches a normal level of 1.5 to prevent renal osteodystrophy.44

Among bisphosphonates, etindronate and pamidronate have proven to be effective. Prednisone is used in early unulcerated plaques.44

Sodium thiosulfate is administered either orally daily or intravenously at the end of haemodialysis for 3–5 months. Sodium thiosulfate offers symptomatic and radiological relief of tissue calcification, displacing calcium from calcium phosphate, to form calcium thiosulfate, which is more soluble than other salts and is excreted either by haemodialysis or by the kidneys. Sodium thiosulfate (25g) is administered intravenously for 30–60min, three times a week after each haemodialysis session. Metabolic acidosis is an important side effect of this drug.44

Dialysis improves this condition through using low calcium dialysate and increasing the frecuency and duration of hemodialysis sessions. Sevelamer is a phosphorus chelator that reduces the intestinal absorption of phosphorus. Calcium–phosphorus product levels below 55mg/dl are the objective.44

In wound management, debridement of necrotic tissue, antibiotics, analgesia, and vacuum dressing are important. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy stimulates angiogenesis and is toxic to anaerobic bacteria. It is used in daily sessions for 60–90min per week with 100% oxygen at 2.5 atmospheres of pressure. Ulcer debridement is coated with partial autologous skin grafts. Successful attempts have been made to coat ulcers with cultured autologous fibroblasts and keratinocytes by adding iloprost infusion (vasodilator prostacyclin analogue) for 35 consecutive days.44

Porphyria cutanea tardaPorphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) occurs in 1.2–18% of patients with CKD and is more frequently observed in patients on haemodialysis. It is a bullous dermatosis caused by phototoxicity due to uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase deficiency, thus causing elevated levels of uroporphyrin and isocoproporphyrin.42,45,46

PCT is classified as Type 1 when it is sporadic and acquired, and is caused by a liver enzyme deficiency. It is associated with hepatitis B and C, HIV-AIDS, alcohol consumption, oestrogen and iron. Type 2 is a hereditary, autosomal dominant disease caused by enzyme deficiency in all tissues. A defect in heme biosynthesis is due to uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase deficiency. It requires less than 30% activity of the enzyme to induce clinical manifestations.42 In CKD, low levels of uroporphyrins are excreted and accumulate, causing phototoxicity reactions. Uroporphyrins cannot be removed by haemodialysis, but high-flux membranes improve elimination.42,45,46

Clinical manifestations include blisters, erosions and crusts that are located on exposed areas, such as the back of hands and forearms and occasionally the face and feet (Fig. 5). These lesions heal with scarring or milia and may be accompanied by hypertrichosis and hyperpigmentation of the face and by esclerodermoid plaques on the hands and face.42,45,46

Laboratory findings include increased serum iron and ferritin, high urine levels of uroporphyrins I and III, and 7–8-carboxyl uroporphyrins, high plasma levels of uroporphyrin and increased levels of isocoproporphyrin III in the faeces.42,45

Histopathology reveals a subepidermal cleft with minimal inflammation and festooned papillary dermis in the base of the cleft. The vessel wall is thickened. Direct immunofluorescence staining indicates linear and granular deposition of immunoglobulin G and C3 in the dermal-epidermal junction and around the vessels.42,45

For the treatment of PCT, sun exposure should be avoided; the use of zinc oxide and titanium oxide-based sunscreen is recommended. Treatment of comorbidities and to avoid exacerbating factors (iron and alcohol consumption, and estrogen using) are also important. Furthermore, it is important to use high-flux membranes (polysulfone) with high-flux dialysis (300ml/h), during 4h of haemodialysis, three times a week.47

Reduce body stores of iron in body stores of iron. Iron induces the enzyme 5-aminolevulinate synthase, which suppresses uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase. Further, it increases conversion of uroporphyrinogen into porphyrins. Phlebotomy is used at a low volume of 100ml, twice weekly for 8 months, followed by 50ml per week thereafter; normal phlebotomy is not tolerated due to anaemia.47 Erythropoietin (20–50U/kg) is administered thrice weekly. When erythropoietin is combined with phlebotomy, a dose of 150–200U/kg, three times per week is used. Deferoxamine (2g) is administered intravenously every haemodialysis session and is associated with long-term adverse effects.47 In refractory cases, two plasma exchange treatments, separated by 48h, are applied. Renal transplantation is the definitive treatment.47

PseudoporphyriaPseudoporphyria is a bullous dermatosis induced by phototoxicity that exhibits the clinical and histopathologic features of PCT; however, normal uroporphyrin levels are observed. The condition is associated with the use of phototoxic drugs such as tetracycline, furosemide, naproxen, amiodarone, nalidixic acid and isotretinoin, and exposure to ultraviolet light A.42,45

Regarding pathogenesis, phototoxic metabolites are formed. Patients with CKD have decreased glutathione levels in erythrocytes, making them susceptible to damage by free radicals. N acetyl-cysteine, a precursor of glutathione with antioxidant properties, is used to effectively treat these patients.42,45

Clinical manifestations include blisters on the back of the hands, forearms and other exposed areas that resolve with scarring and milia. Hypertrichosis on the face or sclerodermoid plaques is rarely observed. Uroporphyrin levels in plasma or urine are normal or slightly elevated.42,45

Histopathology reveals a subepidermal cleft with minimal inflammation and a thick vessel wall. Direct immunofluorescence staining indicates immunoglobulin G and C3 deposition at the dermal-epidermal junction and around vessels.42,45

N-acetyl-cysteine, a precursor of glutathione with antioxidant properties, has been effective therapy in several case reports. An oral dose of 600–1200mg/day offers relief in 4-8 of weeks. Recurrence has been reported after discontinuing medication. It is recommendable to avoid exacerbating factors such as sun exposure, trauma and related drugs.48

Benign nodular calcificationFirm papules, plaques and nodules appear in the joints and fingertips due to metastatic calcification affecting skin. Von Kossa stains calcium deposits black. Treatment is based on reducing calcium–phosphorus products and surgical removal.42

XerosisXerosis is the most common skin manifestation of CKD, occurring in 80% of patients. Etiopathogenic mechanisms include: Decreased hydration of the stratum corneum; decreased sweat gland and sebaceous gland size along with abnormal function related to hypervitaminosis A in dialysis patients, and the use of diuretics. Treatment is based on skin hydration and treatment of pruritus. Repetitive bathing must be avoided and the use of soft, neutral soaps is recommended.45

Pigmentary changesDark brown pigmentation is caused by increased melanin production due to β-melanocyte stimulating hormone accumulation, which is caused by decreased excretion due to kidney failure. The yellowish tinge is caused by the accumulation of carotenoids and urochrome in the skin. Pallor is caused by anaemia due to ineffective erythropoiesis and increased haemolysis. Treatment is based on avoiding sun exposure and involves sunscreen use for hyperpigmentation as well as erythropoietin for anaemia associated with pallor.49,50

Skin infectionsSkin infections are caused by impaired cellular and humoural immunity. They are more common when diabetic nephropathy is the origin. The most common fungal infection is onychomycosis. The most frequent viral infections are common warts, herpes simplex and herpes zoster.49,50

Uremic frostUremic frost is currently a rare manifestation. However when observed, the condition is often accompanied with increased BUN, ranging from 250 to 300mg/dl. It is caused by the accumulation of urea in sweat. When the sweat evaporates, a crystal deposit remains on the skin that appears as a yellowish-white coating on the beard area, neck and trunk.49,50

Nail disordersMees lines. These transverse bands of leukonychia are an alteration of the nail plate that occurs during periods of stress. In addition to its association with CKD, this condition appears in cases of poisoning by arsenic, thallium, and fluorine as well as severe infections, heart disease and malignancy.51

Muehrcke's lines. Double white transverse lines are caused by hypoalbuminemia related to nephrotic syndrome; Muehrcke lines are associated with serum albumin levels less than 2.2g/dl. It originates by vascular compression through local oedema, which causes bleaching of the nail bed. Therefore, no change in position occurs as the nail grows. It has also been observed in cases of cirrhosis, malnutrition and chemotherapy use.52

Lindsay nails (half and half). This condition is related to azotaemia. A white proximal area and a distal pink red-brown area that does not fade under pressure are observed (Fig. 6). No changes are noted with nail growth because the lesion is located in the nail bed. An increase in the number of capillaries in the distal nail plate and a deposit of melanin pigmentation in the distal area are observed. This condition resolves with renal transplantation.53

Other nail changes observed include leukonychia, koilonychia and splinter haemorrhages.49,50

Hair disordersDiffuse alopecia, the most common manifestation, is caused by telogen effluvium; xerosis, pruritus and medication use (Fig. 7). Sparse body hair is also present. Discoloration and dryness of the hair are attributed to a decreased sebum production. Treatment for hair loss is based on meeting nutritional requirements, which are increased in these patients.49,50

Mucosal alterationsXerostomia is the most common abnormality and is caused by oral breathing and dehydration. Macroglossia is also often observed (Fig. 8). Ulcerative stomatitis is observed with urea serum levels greater 150mg/dl and is associated with poor hygiene. Uraemic breath is due to increased urea concentrations in saliva and its transformation into ammonium. The condition is associated with urea levels >200mg/dl. Treatment is based on maintaining good oral hygiene and meeting nutritional requirements.49,50

ConclusionsSkin manifestations are very common in end-stage CKD. Severe renal pruritus is associated with increased mortality and a poor prognosis. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is a relatively new preventable disease associated with gadolinium. In a simple exploration of the nails, some findings indicate alterations in albumin and urea levels. Comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus and secondary hyperparathyroidism can lead to acquired perforating dermatosis and calciphylaxis, respectively. Effective and innovative treatments are available for all of these conditions.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors must have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects mentioned in the article. The author for correspondence must be in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.