After the meeting held by the Spanish Contact Dermatitis and Skin Allergy Research Group (GEIDAC) back in October 2021, changes were suggested to the Spanish Standard Series patch testing. Hydroxyethyl methacrylate (2% pet.), textile dye mixt (6.6% pet.), linalool hydroperoxide (1% pet.), and limonene hydroperoxide (0.3% pet.) were, then, added to the series that agreed upon in 2016. Ethyldiamine and phenoxyethanol were excluded. Methyldibromoglutaronitrile, the mixture of sesquiterpene lactones, and hydroxyisohexyl 3-cyclohexene (Lyral) were also added to the extended Spanish series of 2022.

En la reunión de consenso celebrada por el Grupo Español de Investigación en Dermatitis de Contacto y Alergia Cutánea en octubre del 2021 se estableció la composición actualizada de la batería estándar española de pruebas epicutáneas. A la batería consensuada en 2016 se añaden hidroxi-etil-metacrilato (2% vas.), mezcla colorante textil (6,6% vas.), hidroperóxido de linalool (1% vas.) e hidroperóxido de limoneno (0,3% vas.). Se excluyen la etieldiamina y el fenoxietanol. El metildibromoglutaronitrilo, la mezcla de lactonas sesquiterpénicas y el hidroxi-isohexil 3-ciclohexeno (Lyral) pasan a la batería española ampliada 2022.

The diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is established after performing the necessary patch testing.1 All patients undergoing such testing should be patched with the Spanish Standard Series (SSS)2-4 and, based on the clinical pattern they present, relevant additional batteries should be used. Depending on the peculiarities of each center, the standard series should detect 77% up to 90% of positivities.5

AEDV Spanish Research Working Group on Contact Dermatitis and Cutaneous Immunoallergy (GEIDAC) is responsible for updating the SSB. In October 2021, GEIDAC met to agree on an update of the 2016 SSB. In the SSB review, and subsequently in the European standard review, the GEIDAC proposed that allergens should be included based on prospectively studied data.3,6,7 This means that besides the SSB, there is a group of allergens eligible to be included in the SSB, which have already been listed in the Spanish Extended Series (SES).1,3,8 The two series are dynamic proposals, with updates recommended for expanded standard batteries nearly every 2 years, and national batteries every 5 to 10 years.

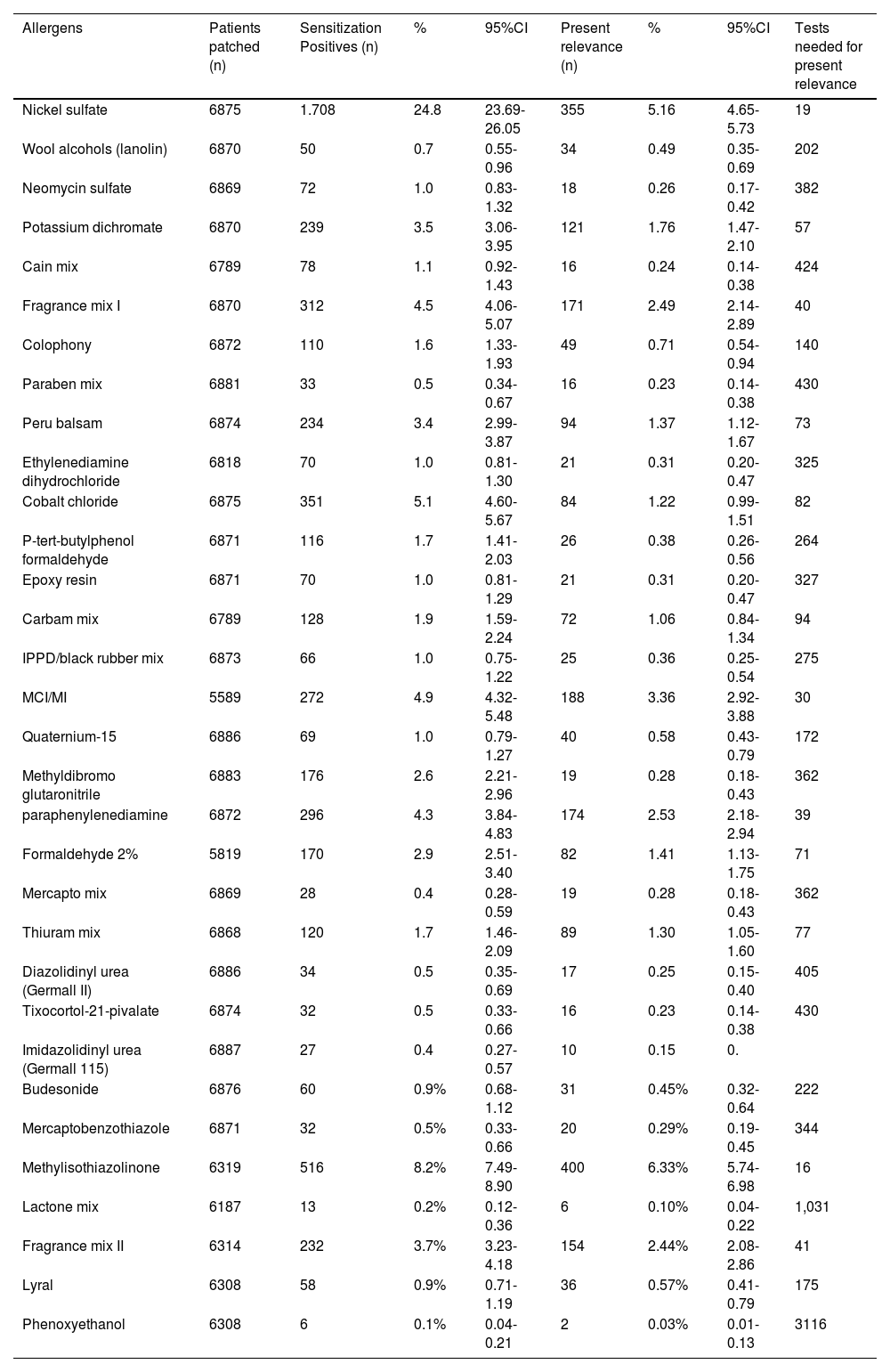

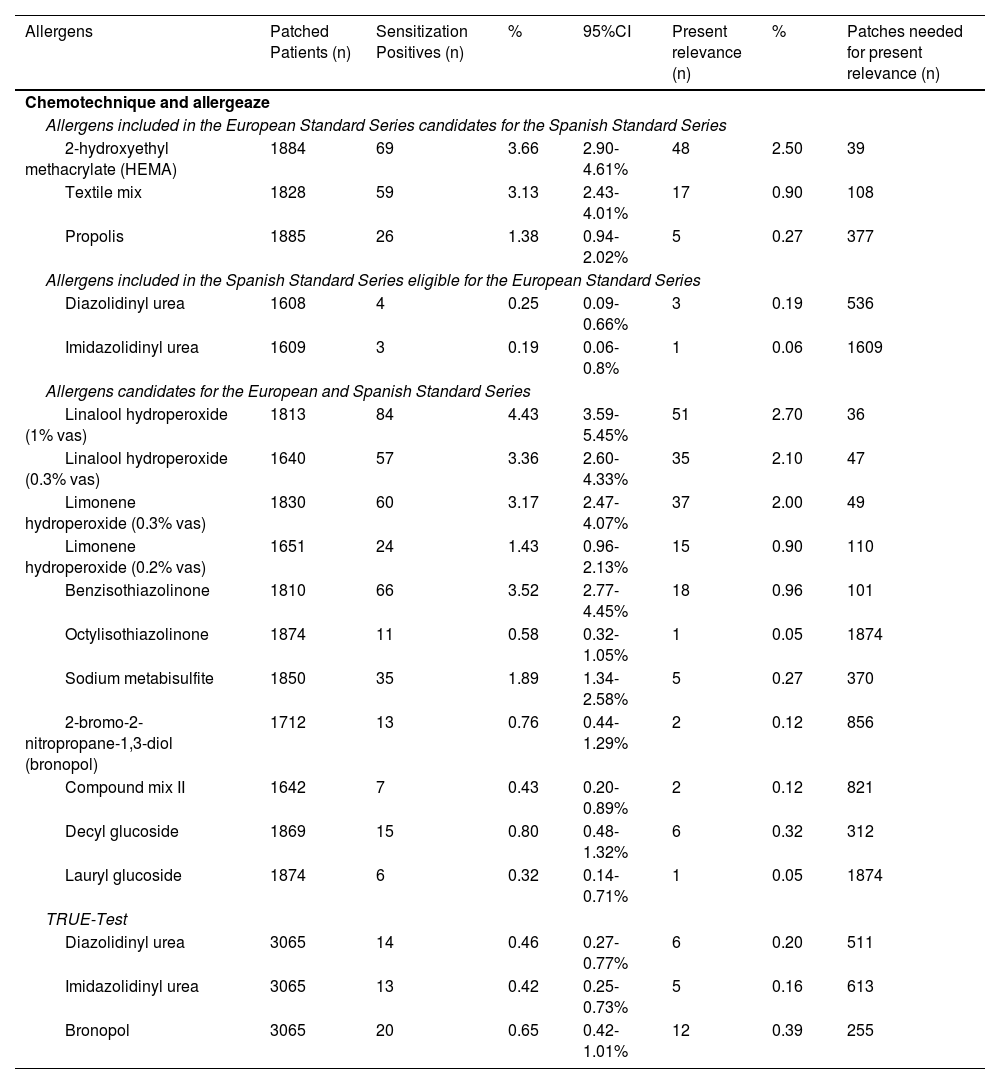

By criterion of authority, an allergen should be listed in a national standard series if it is responsible fo 0.5% to 1% sensitization of unselected patients who underwent patch testing.1 Although this is the most important criterion, its inclusion should also be evaluated based on specific clinical areas (especially occupational and geographical), if it is emerging in neighboring countries, and practical aspects should, also, be taken into consideration such as back surface limitation. Although strictly, the inclusion criterion should be relevant at the present time, subjectivity in assessing this relevance causes this parameter to be used secondarily to the overall sensitization frequency.1 The most significant piece of information regarding present relevance is the number of patched patients required to achieve this relevance,9 as shown in tables 1 and 2.

Patients evaluated with the 2016 Spanish Standard Series (SSS).

| Allergens | Patients patched (n) | Sensitization Positives (n) | % | 95%CI | Present relevance (n) | % | 95%CI | Tests needed for present relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nickel sulfate | 6875 | 1.708 | 24.8 | 23.69-26.05 | 355 | 5.16 | 4.65-5.73 | 19 |

| Wool alcohols (lanolin) | 6870 | 50 | 0.7 | 0.55-0.96 | 34 | 0.49 | 0.35-0.69 | 202 |

| Neomycin sulfate | 6869 | 72 | 1.0 | 0.83-1.32 | 18 | 0.26 | 0.17-0.42 | 382 |

| Potassium dichromate | 6870 | 239 | 3.5 | 3.06-3.95 | 121 | 1.76 | 1.47-2.10 | 57 |

| Cain mix | 6789 | 78 | 1.1 | 0.92-1.43 | 16 | 0.24 | 0.14-0.38 | 424 |

| Fragrance mix I | 6870 | 312 | 4.5 | 4.06-5.07 | 171 | 2.49 | 2.14-2.89 | 40 |

| Colophony | 6872 | 110 | 1.6 | 1.33-1.93 | 49 | 0.71 | 0.54-0.94 | 140 |

| Paraben mix | 6881 | 33 | 0.5 | 0.34-0.67 | 16 | 0.23 | 0.14-0.38 | 430 |

| Peru balsam | 6874 | 234 | 3.4 | 2.99-3.87 | 94 | 1.37 | 1.12-1.67 | 73 |

| Ethylenediamine dihydrochloride | 6818 | 70 | 1.0 | 0.81-1.30 | 21 | 0.31 | 0.20-0.47 | 325 |

| Cobalt chloride | 6875 | 351 | 5.1 | 4.60-5.67 | 84 | 1.22 | 0.99-1.51 | 82 |

| P-tert-butylphenol formaldehyde | 6871 | 116 | 1.7 | 1.41-2.03 | 26 | 0.38 | 0.26-0.56 | 264 |

| Epoxy resin | 6871 | 70 | 1.0 | 0.81-1.29 | 21 | 0.31 | 0.20-0.47 | 327 |

| Carbam mix | 6789 | 128 | 1.9 | 1.59-2.24 | 72 | 1.06 | 0.84-1.34 | 94 |

| IPPD/black rubber mix | 6873 | 66 | 1.0 | 0.75-1.22 | 25 | 0.36 | 0.25-0.54 | 275 |

| MCI/MI | 5589 | 272 | 4.9 | 4.32-5.48 | 188 | 3.36 | 2.92-3.88 | 30 |

| Quaternium-15 | 6886 | 69 | 1.0 | 0.79-1.27 | 40 | 0.58 | 0.43-0.79 | 172 |

| Methyldibromo glutaronitrile | 6883 | 176 | 2.6 | 2.21-2.96 | 19 | 0.28 | 0.18-0.43 | 362 |

| paraphenylenediamine | 6872 | 296 | 4.3 | 3.84-4.83 | 174 | 2.53 | 2.18-2.94 | 39 |

| Formaldehyde 2% | 5819 | 170 | 2.9 | 2.51-3.40 | 82 | 1.41 | 1.13-1.75 | 71 |

| Mercapto mix | 6869 | 28 | 0.4 | 0.28-0.59 | 19 | 0.28 | 0.18-0.43 | 362 |

| Thiuram mix | 6868 | 120 | 1.7 | 1.46-2.09 | 89 | 1.30 | 1.05-1.60 | 77 |

| Diazolidinyl urea (Germall II) | 6886 | 34 | 0.5 | 0.35-0.69 | 17 | 0.25 | 0.15-0.40 | 405 |

| Tixocortol-21-pivalate | 6874 | 32 | 0.5 | 0.33-0.66 | 16 | 0.23 | 0.14-0.38 | 430 |

| Imidazolidinyl urea (Germall 115) | 6887 | 27 | 0.4 | 0.27-0.57 | 10 | 0.15 | 0. | |

| Budesonide | 6876 | 60 | 0.9% | 0.68-1.12 | 31 | 0.45% | 0.32-0.64 | 222 |

| Mercaptobenzothiazole | 6871 | 32 | 0.5% | 0.33-0.66 | 20 | 0.29% | 0.19-0.45 | 344 |

| Methylisothiazolinone | 6319 | 516 | 8.2% | 7.49-8.90 | 400 | 6.33% | 5.74-6.98 | 16 |

| Lactone mix | 6187 | 13 | 0.2% | 0.12-0.36 | 6 | 0.10% | 0.04-0.22 | 1,031 |

| Fragrance mix II | 6314 | 232 | 3.7% | 3.23-4.18 | 154 | 2.44% | 2.08-2.86 | 41 |

| Lyral | 6308 | 58 | 0.9% | 0.71-1.19 | 36 | 0.57% | 0.41-0.79 | 175 |

| Phenoxyethanol | 6308 | 6 | 0.1% | 0.04-0.21 | 2 | 0.03% | 0.01-0.13 | 3116 |

Consensus document on the 2022 Spanish Standard Series (SSS).

Patients patch tested with the candidate allergen series or 2019 Spanish Extended Series (SES).

| Allergens | Patched Patients (n) | Sensitization Positives (n) | % | 95%CI | Present relevance (n) | % | Patches needed for present relevance (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotechnique and allergeaze | |||||||

| Allergens included in the European Standard Series candidates for the Spanish Standard Series | |||||||

| 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA) | 1884 | 69 | 3.66 | 2.90-4.61% | 48 | 2.50 | 39 |

| Textile mix | 1828 | 59 | 3.13 | 2.43-4.01% | 17 | 0.90 | 108 |

| Propolis | 1885 | 26 | 1.38 | 0.94-2.02% | 5 | 0.27 | 377 |

| Allergens included in the Spanish Standard Series eligible for the European Standard Series | |||||||

| Diazolidinyl urea | 1608 | 4 | 0.25 | 0.09-0.66% | 3 | 0.19 | 536 |

| Imidazolidinyl urea | 1609 | 3 | 0.19 | 0.06-0.8% | 1 | 0.06 | 1609 |

| Allergens candidates for the European and Spanish Standard Series | |||||||

| Linalool hydroperoxide (1% vas) | 1813 | 84 | 4.43 | 3.59-5.45% | 51 | 2.70 | 36 |

| Linalool hydroperoxide (0.3% vas) | 1640 | 57 | 3.36 | 2.60-4.33% | 35 | 2.10 | 47 |

| Limonene hydroperoxide (0.3% vas) | 1830 | 60 | 3.17 | 2.47-4.07% | 37 | 2.00 | 49 |

| Limonene hydroperoxide (0.2% vas) | 1651 | 24 | 1.43 | 0.96-2.13% | 15 | 0.90 | 110 |

| Benzisothiazolinone | 1810 | 66 | 3.52 | 2.77-4.45% | 18 | 0.96 | 101 |

| Octylisothiazolinone | 1874 | 11 | 0.58 | 0.32-1.05% | 1 | 0.05 | 1874 |

| Sodium metabisulfite | 1850 | 35 | 1.89 | 1.34-2.58% | 5 | 0.27 | 370 |

| 2-bromo-2-nitropropane-1,3-diol (bronopol) | 1712 | 13 | 0.76 | 0.44-1.29% | 2 | 0.12 | 856 |

| Compound mix II | 1642 | 7 | 0.43 | 0.20-0.89% | 2 | 0.12 | 821 |

| Decyl glucoside | 1869 | 15 | 0.80 | 0.48-1.32% | 6 | 0.32 | 312 |

| Lauryl glucoside | 1874 | 6 | 0.32 | 0.14-0.71% | 1 | 0.05 | 1874 |

| TRUE-Test | |||||||

| Diazolidinyl urea | 3065 | 14 | 0.46 | 0.27-0.77% | 6 | 0.20 | 511 |

| Imidazolidinyl urea | 3065 | 13 | 0.42 | 0.25-0.73% | 5 | 0.16 | 613 |

| Bronopol | 3065 | 20 | 0.65 | 0.42-1.01% | 12 | 0.39 | 255 |

Data already published. Obtained from Hernández-Fernández et al.8.

Progress in digital technology has had an impact on ACD. In 2018, a multicenter registry supported by AEDV Research Unit was created by GEIDAC members, and is the data source in this document.10

Material and methodsThe structure of the Spanish Registry of Research in Allergic and Contact Dermatitis (REIDAC) has been previously described.10 Data from the SSB were obtained from the general form (table 1). Afterwards, a form was created for candidate allergens of the ESB (table 2). Data from the SSB were obtained from the beginning of the registry (June 1st, 2018) through December 2020. Data from the ESB were collected from January 1st, 2019 through December 31st, 2020. In October 2021, a meeting was held to establish the new SSB and ESB. Previously, the working group completed an online survey for the initial assessment of permanence, exclusion, or inclusion of each allergen in the proposed series.

ResultsA total of 6870 patients were evaluated with the 2016 SSB and 1890 with the ESB. The results are shown in tables 1 and 2.

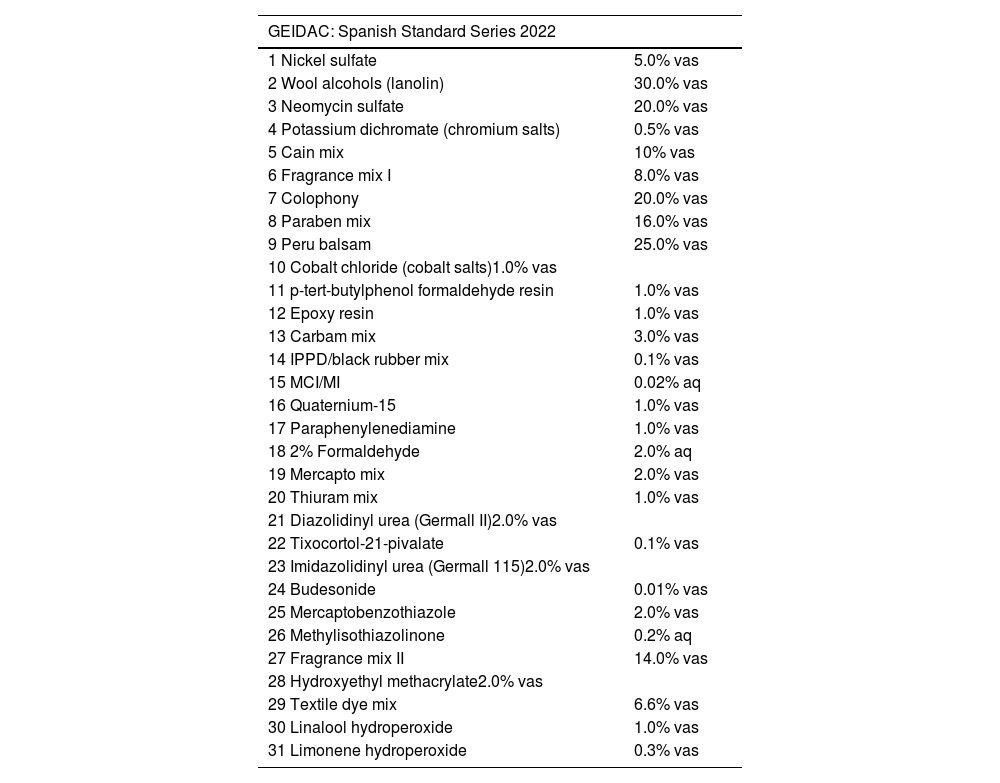

Consensus meetingFor consistency with the European standard and expanded series, allergens from the Spanish batteries must include allergens from both European batteries. For operational criteria, it was agreed that the SSB should list nearly 30 allergens. Similarly, the concentration of cain mix was updated according to the European standard series, including 5% benzocaine11 (tables 3 and 4).

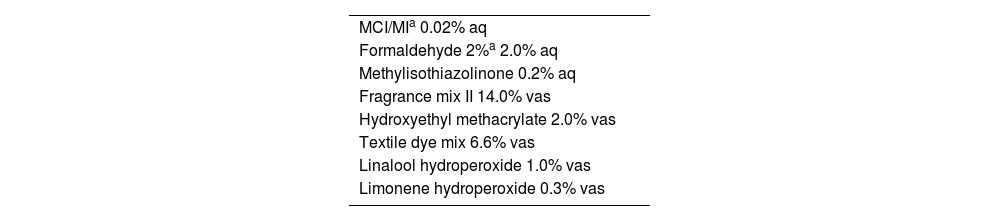

2022 Spanish Standard Series (SSS).

| GEIDAC: Spanish Standard Series 2022 | |

|---|---|

| 1 Nickel sulfate | 5.0% vas |

| 2 Wool alcohols (lanolin) | 30.0% vas |

| 3 Neomycin sulfate | 20.0% vas |

| 4 Potassium dichromate (chromium salts) | 0.5% vas |

| 5 Cain mix | 10% vas |

| 6 Fragrance mix I | 8.0% vas |

| 7 Colophony | 20.0% vas |

| 8 Paraben mix | 16.0% vas |

| 9 Peru balsam | 25.0% vas |

| 10 Cobalt chloride (cobalt salts)1.0% vas | |

| 11 p-tert-butylphenol formaldehyde resin | 1.0% vas |

| 12 Epoxy resin | 1.0% vas |

| 13 Carbam mix | 3.0% vas |

| 14 IPPD/black rubber mix | 0.1% vas |

| 15 MCI/MI | 0.02% aq |

| 16 Quaternium-15 | 1.0% vas |

| 17 Paraphenylenediamine | 1.0% vas |

| 18 2% Formaldehyde | 2.0% aq |

| 19 Mercapto mix | 2.0% vas |

| 20 Thiuram mix | 1.0% vas |

| 21 Diazolidinyl urea (Germall II)2.0% vas | |

| 22 Tixocortol-21-pivalate | 0.1% vas |

| 23 Imidazolidinyl urea (Germall 115)2.0% vas | |

| 24 Budesonide | 0.01% vas |

| 25 Mercaptobenzothiazole | 2.0% vas |

| 26 Methylisothiazolinone | 0.2% aq |

| 27 Fragrance mix II | 14.0% vas |

| 28 Hydroxyethyl methacrylate2.0% vas | |

| 29 Textile dye mix | 6.6% vas |

| 30 Linalool hydroperoxide | 1.0% vas |

| 31 Limonene hydroperoxide | 0.3% vas |

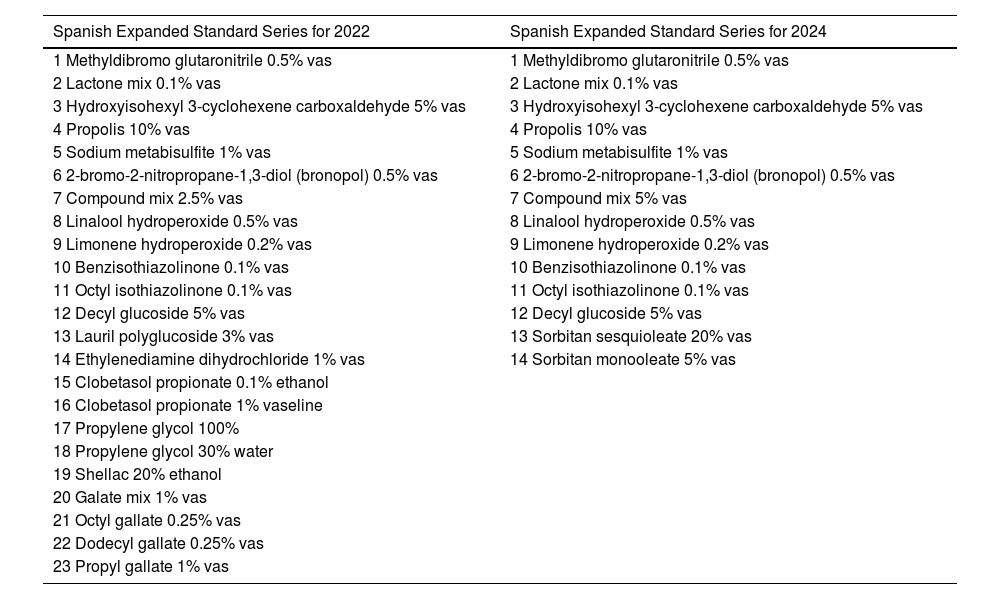

Proposals for Spanish Extended Series for 2022 and 2024.

| Spanish Expanded Standard Series for 2022 | Spanish Expanded Standard Series for 2024 |

|---|---|

| 1 Methyldibromo glutaronitrile 0.5% vas | 1 Methyldibromo glutaronitrile 0.5% vas |

| 2 Lactone mix 0.1% vas | 2 Lactone mix 0.1% vas |

| 3 Hydroxyisohexyl 3-cyclohexene carboxaldehyde 5% vas | 3 Hydroxyisohexyl 3-cyclohexene carboxaldehyde 5% vas |

| 4 Propolis 10% vas | 4 Propolis 10% vas |

| 5 Sodium metabisulfite 1% vas | 5 Sodium metabisulfite 1% vas |

| 6 2-bromo-2-nitropropane-1,3-diol (bronopol) 0.5% vas | 6 2-bromo-2-nitropropane-1,3-diol (bronopol) 0.5% vas |

| 7 Compound mix 2.5% vas | 7 Compound mix 5% vas |

| 8 Linalool hydroperoxide 0.5% vas | 8 Linalool hydroperoxide 0.5% vas |

| 9 Limonene hydroperoxide 0.2% vas | 9 Limonene hydroperoxide 0.2% vas |

| 10 Benzisothiazolinone 0.1% vas | 10 Benzisothiazolinone 0.1% vas |

| 11 Octyl isothiazolinone 0.1% vas | 11 Octyl isothiazolinone 0.1% vas |

| 12 Decyl glucoside 5% vas | 12 Decyl glucoside 5% vas |

| 13 Lauril polyglucoside 3% vas | 13 Sorbitan sesquioleate 20% vas |

| 14 Ethylenediamine dihydrochloride 1% vas | 14 Sorbitan monooleate 5% vas |

| 15 Clobetasol propionate 0.1% ethanol | |

| 16 Clobetasol propionate 1% vaseline | |

| 17 Propylene glycol 100% | |

| 18 Propylene glycol 30% water | |

| 19 Shellac 20% ethanol | |

| 20 Galate mix 1% vas | |

| 21 Octyl gallate 0.25% vas | |

| 22 Dodecyl gallate 0.25% vas | |

| 23 Propyl gallate 1% vas |

Considering that the dilution support of the allergens is expressed in table 3, the criterion for allowing the TRUE-Test® (Thin-layer Rapid Use Epicutaneous-Test, SmartPractice Denmark ApS, Hillerød, Denmark) as support for the ESB was kept except for the concentrations of chloromethylisothiazolinone-methylisothiazolinone and formaldehyde.12 For clinicians still using the TRUE Test®, it is essential to expand the patches studied according to Table 5.

Allergens that need to be added to the TRUE-Test® to complete the 2022 Spanish Standard Series (SSS).

The most controversial allergen was methyldibromo glutaronitrile because, although the sensitization rate justified that it should stay, the relevance of positivity is quite questionable.13,14 Given the need to maintain active surveillance on the molecule, it was decided to exclude it from the SSB and list it in the ESB.15,16 Lyral—individually patched and included in fragrance mix II—presents very low sensitization rates and most likely covered by fragrance mix II, and has been banned by the European legislation. Although lyral has been removed from the SSB it temporarily remains in the ESB17,18 for consistency with the European series. Ethylenediamine3,4,19–22 and phenoxyethanol—already controversial in the 2012 meeting—were removed from the SSB.3,23

In GEIDAC administrative meeting of September 2023, a new ESB was approved for use in centers starting January 1st, 2024 (table 4).

DiscussionIf we compare the results of the SSB with those previously published,2,34 it is surprising that, except for the exchange of methylchloroisothiazolinone/methylisothiazolinone (MCI/MI) for methylisothiazolinone (MI), very few changes have been reported regarding the sensitization frequency of allergens.8,24

MetalThe group of metals are the most frequent sensitizers in all published series.25 Nickel sulfate has a high sensitization rate (24.8%). Nonetheless, a slight decrease has been reported in other European countries.26 Cobalt chloride continues to show sensitization rates of up to 4.87%.24 Contact sources justify both the high sensitization rates reported and the possibility of co-sensitization due to common exposure in the workplace, jewelry, or tattoos.27,28 Potassium dichromate has undergone some nonsignificant variation in its frequency, possibly due to legislative changes in its main contact source, cement.24,29

BiocidesDue to exposure risk, biocides form one of the most important groups since they are present in both industrial and cosmetic products. The latest sensitization data to MI from 2022 provide sensitization rates of 7.08% vs 4.49% for the MCI/MI mixture.24 In 2018, MI showed a sensitization rate of up to 8.55%, indicating that, although high, there is a downward trend in sensitization rates.24

There are two other 2-isothiazolinones under study: benzothiazolinone (BIT) and octylisothiazolinone (OIT). Both are prohibited in cosmetics. The main exposure source is industrial products, detergents, and paints.29,30-33 BIT sensitization data in 2022 was 3.5%,8 which justifies its possible inclusion in the SSB. Due to the low relevance of positive tests, it was decided to keep it in the ESB. The OIT sensitization rate to was very low, remaining in the ESB for consistency with the European battery only8 (tables 3 and 4).

Formaldehyde and formaldehyde releasers represent the second most important group of biocides.31 After changing patch concentration to 2% formaldehyde in water in 2014, many more cases of ACD can be established.12,32,33 Recent positivity data to formaldehyde reached 2.9% in the latest REIDAC analysis. Compared with the TRUE-Test, the latter detects only one-third of sensitization cases.34 Of note that formaldehyde is not a good marker for sensitization to formaldehyde releasers.35 Although quaternium-15 (formaldehyde releaser) has been removed from the European series, it is still in the SSB with a positivity rate of 1%.36 More for historical reasons than justified by its sensitization rates, the SSB still lists imidazolidinyl urea (0.4% positivity) and diazolidinyl urea (0.5% positivity), while bronopol can be found in the ESB8 even though the prevalence of positives is similar vs the other 2 above-mentioned formaldehyde releasers.37

Parabens are esters of p-hydroxybenzoic acid used as preservatives in cosmetic products and drugs. Although they have been identified as responsible for certain carcinogenic risk,38 they are still unrestrictidely being used. The mixture consists of 4 parabens (methyl p-hydroxybenzoate 4%, propyl p-hydroxybenzoate 4%, butyl p-hydroxybenzoate 4%, and ethyl p-hydroxybenzoate 4%). One of the SSB suppliers only lists ethylparaben. Although positivity rate is only 0.5%, parabens are being kept in the SSB.

During the study period, the sensitization rate of sodium metabisulfite was monitored. In Europe, a 3.75% sensitization rate has been reported,6 while in Spain it has dropped down to 2.1%.39 The percentage of present relevance according to European data is 50% (25% in the Spanish series), indicating the need to better understand the sources of sensitization, remaining in the ESB.40-42

FragrancesSensitization rates to the main fragrance markers (fragrance mix I and II), and Peru balsam (Myroxylon pereirae resin), continue to be high. Sensitization rates to fragrance mix I, fragrance mix II, and Peru balsam were 4.1%, 3.41%, and 3.22%, respectively.24 In 2021, the sensitization rate to specific allergens in the fragrance series was published, with geraniol, isoeugenol, and Evernia prunastri being the most common allergens of all.43 Citral and lyral were more common in cases of professional origin.43

None of the 3 above-mentioned fragrance markers lists the terpenoids linalool and limonene or their hydroperoxides (considered responsible for sensitization).44 Given the high positivity rate (4.6% for linalool and 3.3% for limonene) and the established positive relevance to both allergens (61.4% for linalool and 61.7% for limonene), they have been added to the SSB.8 Interpreting the reactions to these 2 allergens can be difficult as they can be considered irritants,45,46 which is why the 0.5% concentration for linalool hydroperoxide and the 0.2% for limonene hydroperoxide in the ESB is still under consideration.

Dyes/paraphenylenediamineNationwide, paraphenylenediamine (PPD) continues to be the go-to sensitizer in dyes.24 The cause of sensitization mainly depends on the patient's age.47 In children, it is associated with contact with adulterated henna tattoos,48 while middle-aged individuals, it has been associated with the hairdressing career, and subsequently with hair dye users.46

The textile mixture was listed as a candidate allergen back in the 2019 ESB with a sensitization rate in 2022 of up to 3.1%,8,24 which justifies its addition to the SSB8. This mix allows for the study of generalized or flexural ACD of clothing origin, which should be taken into consideration in the differential diagnosis with atopic dermatitis.32,49

PlantsThis is a very heterogeneous and difficult group to manage. The mix of sesquiterpene lactones and composite mixture are internationally recognized markers. For consistency with the European series, the two mixtures have been included in the ESB. The composite mixture (Tanacetum vulgare, Arnica montana, Parthenolide, Chamomilla romana, Chamomilla recutita, and Tanacetum millefolium) has a 2.31% sensitization rate in Europe26 and a 0.43% sensitization rate in Spain.8 In the last European review, it was decided to increase its concentration from 2.5% up to 5%.7,50,51

Other allergens in the SSB, such as colophony, propolis, or fragrances, could be less specific markers of plant sensitization.

Adhesives/gluesEpoxy resin continues to be considered an occupational sensitization marker,52 although there has been an increase in recreational cases,53-55 remaining in the SSB. The 4-tert-butylphenol formaldehyde resin is a good marker,56 especially for foot dermatitis.57 In recent years, and in relation to the sensitization epidemic to acrylates in users and professionals of nail cosmetics, hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA) has been added to both the European standard series and the SSB. Other sources of sensitization are inks, lacquers, adhesives, and dental and medical materials. The sensitization rate for HEMA was 3.66%, which justifies its inclusion in the SSB, although the most recent data reveal a higher sensitization rate.24

Vulcanization acceleratorsConsidering chronic hand eczema as the main reason for patient referral to Contact Dermatitis units, this group of allergens is a must in the SSB to rule out sensitization to gloves used as a protective measure. The thiuram mixture remains in the European series, but unlike these, in Spain, carbamate mixture remains (relevant sensitization rate at 1.9%).24 The positivity rate for the mercapto mixture is 0.4%, and for mercaptobenzothiazole, 0.5%. The important thing is that the two of them associate a positive relevance > 60%, which keeps them in the SSB.

Vehicles and emulsifiersGlucosides are non-ionic surfactants that show high sensitization in studies conducted in the United States.58 This rate is lower in Europe and even lower in the Spanish population.59 Decyl glucoside remains in the ESB for consistency with the European battery.

The rise of biocosmetics has justified interest in propolis. This hapten remains listed in the European standard series since 2019.60 The sensitization rate in Central Europe from 2015 through 2018 was 3.94%,61 while in Spain it stands at 1.38%.8 Due to geographical heterogeneity in its sensitization,62 ands its low—though non-negligible—sensitization rate in Spain, its presence in the ESB is justified to determine the areas where it is truly relevant.

Propylene glycol is an aliphatic alcohol, which is widely used in the industrial, agri-food, health care, and cosmetic fields. It presents both irritative and allergic reactions, with the optimal concentration for use in patches still to be elucidated. Due to its ubiquity, it was listed as a candidate allergen back in the 2022 ESB at concentrations of 30% and 100%.

The use of shellac, or shellac gum, has increased in the context of “natural” molecules. It is the purified form of the resin produced by the female bug of the kerria lacca. It is used in the wood industry, advanced technology, printing, cosmetics, food, and pharmaceuticals. The publication of cases in Spain related to the food industry and the use of cosmetics suggested its study in the 2023 ESB.63-65

Sorbitan oleate and sorbitan sesquioleate were listed in the expanded European series in July 2023.7 These haptens are part of the vehicles used in other allergens, such as fragrances, Peru balsam, HEMA, and sunscreens at wholesale purchasing level.66 The need for discriminating allergen sensitization or their vehicle has motivated their addition to the 2024 ESB.

DrugsIn drug-induced contact dermatitis, the first diagnostic suspicion should be directed towards excipients, including fragrances and Peru balsam. As active ingredients, neomycin stands out, which, although with low sensitization rates, is still considered an allergen used in creams for the management of wounds, ulcers, and burns.

Within the European and Spanish Standard Series, topical corticosteroids are represented by tixocortol pivalate and budesonide. At the meeting, the need for a marker of Group III corticosteroids, from Baeck's classification, was reported, so clobetasol propionate was proposted to be listed in the 2022 ESB.67

Hand dermatitis and intolerance to cosmetics are the 2 most important reasons to seek medical attention in Contact Dermatitis unit, and without detriment to the need for specific batteries, the SSB must cover the higher number of patients treated.5 Since both the hands and the facial region are the main affected areas, the SSB must include the main allergens involved in these locations. Considering the above-mentioned premise, metals, biocides, fragrances, and vulcanization accelerators lead the SSB list.

ConclusionsThe SSB is updated and should be used in all patients undergoing contact patch testing nationwide from January 2022 (Table 3).

FundingThe REIDAC is sponsored by the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (Fundación Piel Sana), and has received funding from the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2022/04/11/pdfs/BOE-A-2022-5975.pdf) and Sanofi®. REIDAC sponsors did not intervene in the proposal for preparation, design, data mining, analysis and interpretation, drafting, revision, approval, or logistical support associated with the present manuscript.

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Dr. Ignacio Garcia, Dr. Miguel Angel Descalzo, and Dr. Marina de Vega from AEDV Research Unit for their invaluable contribution to the meticulous exploitation and maintenance of the registry.