Staphylococcus lugdunensis belongs to the group of coagulase-negative staphylococci. The aim of this report was to review the clinical and microbiologic features of cases of S. lugdunensis skin infections.

Material and methodsObservational study of all cases of skin infections in which S. lugdunensis was isolated by the microbiology department of Hospital General San Jorge in Huesca, Spain, between 2009 and 2016.

ResultsWe studied the cases of 16 patients. The most frequent site of infection was the inguinal-perineal region (n = 6, 37.5%), and pustules were the most common presentation (n = 5, 31.3%). Response to treatment was good in 87.6% of the patients (n = 14). However, infection recurred in 3 patients, 2 of whom were on anti-TNF therapy.

ConclusionsS. lugdunensis should be considered a possible cause of infection when it is isolated in both skin and subcutaneous tissues, especially in patients on biologic therapies.

Staphylococcus lugdunensis pertenece al grupo de los estafilococos coagulasa negativos. El objetivo del estudio es revisar las características clínicas y microbiológicas de los pacientes diagnosticados de una infección cutánea por S. lugdunensis.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional retrospectivo de todos los casos de infecciones cutáneas en las que se aisló S. lugdunensis diagnosticados entre 2009 y 2016 en el Servicio de Microbiología del Hospital San Jorge de Huesca.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 16 pacientes. La localización más frecuente fue la zona inguinoperineal (n = 6, 37,5%) y la forma de presentación más habitual fueron las pústulas (n = 5, 31,3%). El 87,6% de los pacientes (n = 14) mostraron buena respuesta al tratamiento; sin embargo, 3 pacientes recurrieron. De ellos, 2 estaban en tratamiento con un anti-TNF.

ConclusiónS. lugdunensis debería considerarse el posible agente causal de la infección cuando se aísla tanto en piel como en tejido celular subcutáneo, especialmente en pacientes que están recibiendo tratamiento biológico.

Staphylococcus lugdunensis belongs to the group of coagulase-negative staphylococci (CoNS). First described in 1988 by Freney in Lyon, France,1 this emerging pathogen is more virulent than other CoNS and can cause infections with high mortality.2

S lugdunensis is a commensal CoNS in areas with apocrine glands,3 and causes infections of the skin and subcutaneous cell tissue, generally resulting in abscess formation.4 Patients with predisposing conditions such as diabetes or tumors are at greater risk of acquiring S lugdunensis infection, although deep and superficial infections have also been described in healthy individuals,5 in which the skin is the main point of entry.

In this study we sought to review the clinical and microbiological characteristics of patients in our center who were diagnosed with skin infections from which S lugdunensis was isolated, as well as the treatments applied and the course of the infection.

Material and MethodsWe performed a retrospective observational study of all cases of skin infections for which microbiological culture revealed the presence of S lugdunensis at the Microbiology Service of Hospital San Jorge de Huesca between 2009 and 2016.

The following variables were recorded: age; sex; associated systemic diseases and their treatment; location and type of skin lesion; treatment and evolution; and other microorganisms concomitantly isolated from the same lesion.

Microbiological diagnosis was based on culture of the samples in standard media. Microorganism identification and antibiotic sensitivity tests were performed using MicroScan® (Beckman Coulter), applying the criteria of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Identification was confirmed using the ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) test and the pyrrolidonyl-arylamidase (PYR) test (Rosco Diagnostica A/S, Denmark).

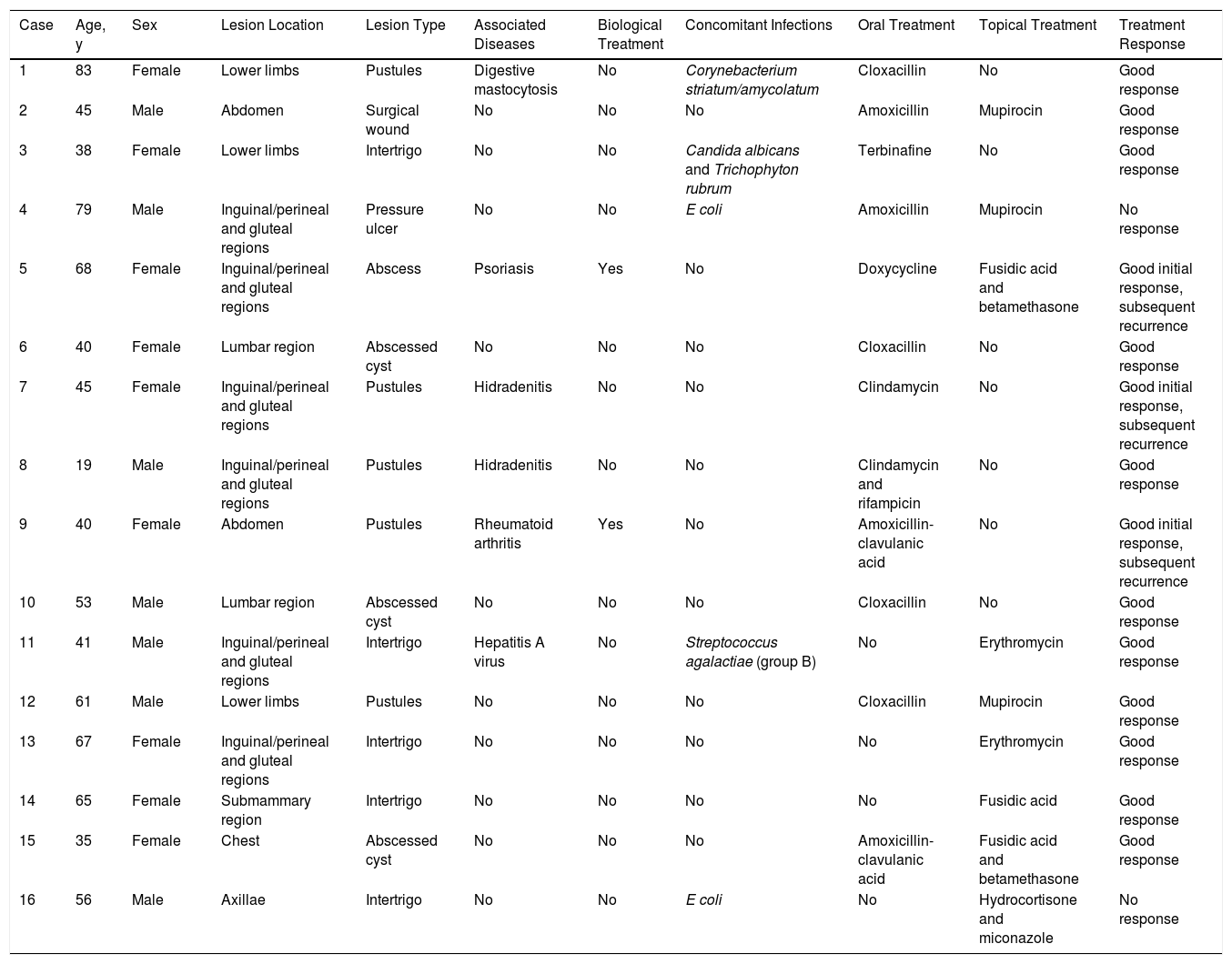

ResultsTable 1 summarizes the characteristics of the sample population, which consisted of 16 patients (9 women, 7 men) with a mean age of 52.19 years (range, 19–83 y). Six patients (37.5%) had underlying systemic diseases.

Clinical Characteristics, Coinfection Status, Treatment, and Infection Course

| Case | Age, y | Sex | Lesion Location | Lesion Type | Associated Diseases | Biological Treatment | Concomitant Infections | Oral Treatment | Topical Treatment | Treatment Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 83 | Female | Lower limbs | Pustules | Digestive mastocytosis | No | Corynebacterium striatum/amycolatum | Cloxacillin | No | Good response |

| 2 | 45 | Male | Abdomen | Surgical wound | No | No | No | Amoxicillin | Mupirocin | Good response |

| 3 | 38 | Female | Lower limbs | Intertrigo | No | No | Candida albicans and Trichophyton rubrum | Terbinafine | No | Good response |

| 4 | 79 | Male | Inguinal/perineal and gluteal regions | Pressure ulcer | No | No | E coli | Amoxicillin | Mupirocin | No response |

| 5 | 68 | Female | Inguinal/perineal and gluteal regions | Abscess | Psoriasis | Yes | No | Doxycycline | Fusidic acid and betamethasone | Good initial response, subsequent recurrence |

| 6 | 40 | Female | Lumbar region | Abscessed cyst | No | No | No | Cloxacillin | No | Good response |

| 7 | 45 | Female | Inguinal/perineal and gluteal regions | Pustules | Hidradenitis | No | No | Clindamycin | No | Good initial response, subsequent recurrence |

| 8 | 19 | Male | Inguinal/perineal and gluteal regions | Pustules | Hidradenitis | No | No | Clindamycin and rifampicin | No | Good response |

| 9 | 40 | Female | Abdomen | Pustules | Rheumatoid arthritis | Yes | No | Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | No | Good initial response, subsequent recurrence |

| 10 | 53 | Male | Lumbar region | Abscessed cyst | No | No | No | Cloxacillin | No | Good response |

| 11 | 41 | Male | Inguinal/perineal and gluteal regions | Intertrigo | Hepatitis A virus | No | Streptococcus agalactiae (group B) | No | Erythromycin | Good response |

| 12 | 61 | Male | Lower limbs | Pustules | No | No | No | Cloxacillin | Mupirocin | Good response |

| 13 | 67 | Female | Inguinal/perineal and gluteal regions | Intertrigo | No | No | No | No | Erythromycin | Good response |

| 14 | 65 | Female | Submammary region | Intertrigo | No | No | No | No | Fusidic acid | Good response |

| 15 | 35 | Female | Chest | Abscessed cyst | No | No | No | Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | Fusidic acid and betamethasone | Good response |

| 16 | 56 | Male | Axillae | Intertrigo | No | No | E coli | No | Hydrocortisone and miconazole | No response |

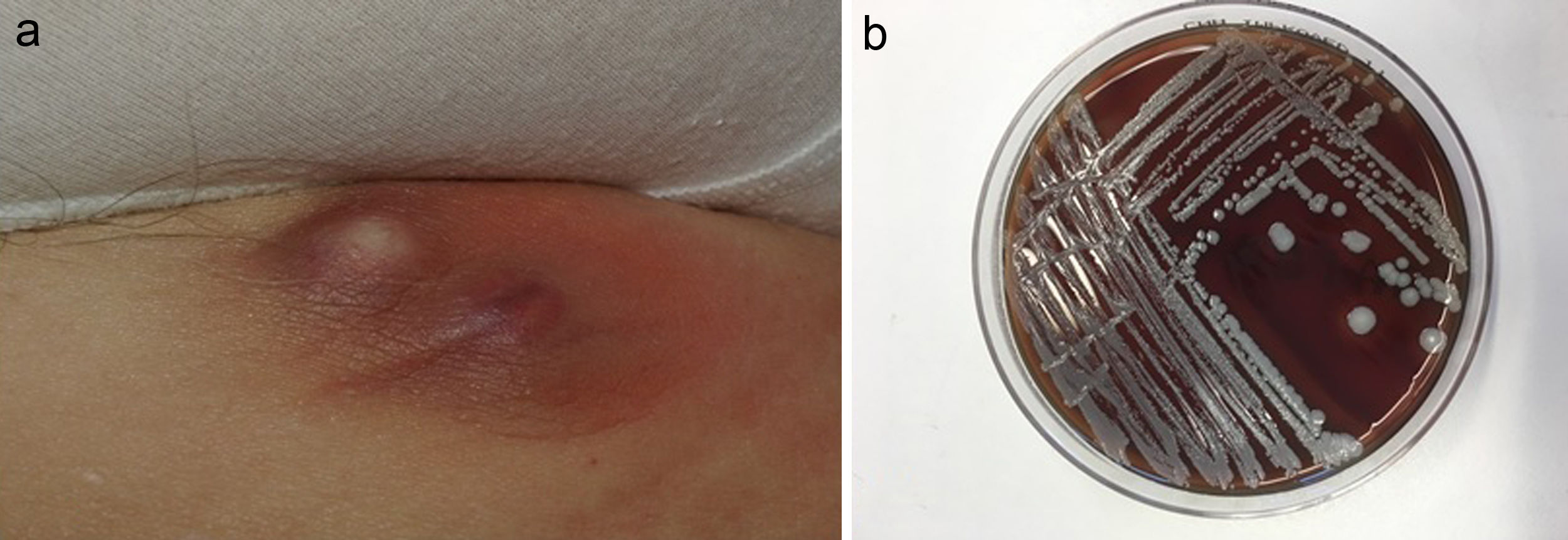

The most commonly affected location was the inguinal/perineal area (n = 6, 37.5%), followed by the lower extremities (n = 3, 18.8%). The most common clinical presentations were pustules (n = 5, 31.3%), intertrigo-type lesions (n = 5, 31.3%), and abscessed cysts (n = 3, 18.8%) (Fig. 1A). The presence of an abscess was reported in only 1 patient.

S lugdunensis was the only pathogen isolated in cultures from 11 (68.8%) of the 16 patients. The microorganism most frequently isolated concomitantly with S lugdunensis was Escherichia coli (n = 2, 12.5%). A curious feature of the S lugdunensis samples isolated on blood agar was a characteristic smell of cured pork.

An antibiogram performed for all samples revealed antibiotic sensitivity of all S lugdunensis isolates, except for one that showed resistance to clindamycin, erythromycin, fosfomycin, and tetracycline. Fungal culture was performed in 6 patients, 5 of whom had suspected intertrigo.

Oral treatment, the most common of which was oral penicillin, was received by 75% of patients (n = 12). Topical treatment was received by 56.3% (n = 9) of patients, of whom 5 received associated oral antibiotic treatment. Mupirocin (n = 3, 18.8%) and erythromycin (n = 2, 12.5%) were the most frequently prescribed topical antibiotics among patients who received topical treatment. Of the 5 patients with intertrigo-like lesions, only one presented coinfection (with Candida albicans and Trichophyton rubrum), which responded adequately to oral terbinafine. In cases involving abscesses or abscessed cysts, the lesions were drained.

A good treatment response was observed in 87.6% of patients (n = 14). Two patients, both of whom had E coli coinfections, did not respond to treatment. Three patients who showed a good initial response experienced recurrence (2 episodes each). Of these 3 patients, 2 were being treated with anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents.

DiscussionDespite forming part of the skin microbiota, S lugdunensis is of great pathogenic importance and, like Staphylococcus aureus, can cause invasive, highly virulent community and nosocomial infections.6

In our series, skin infections caused by S lugdunensis were mostly mild and predominantly affected the inguinal/perineal area. The most frequent clinical presentations were intertrigo-like and pustular lesions. Recurrence was observed only in patients treated with anti-TNF agents.

The majority of S lugdunensis infections reported in the literature present as infections of the skin or subcutaneous tissue that result in abscess formation.7,8 Among 29 cases recently described by Zaaroura et al,9 the most frequent presentation was pustulosis/folliculitis (16 patients). In line with those findings, pustules and intertrigo were the most common presentations (5 cases of each) in our series.

The most frequently affected locations in our study population coincided with those reported in previous studies. These include the inguinal/perineal area,7,10 abdomen, lower extremities,11 and mammary region,5 all of which are areas in which S lugdunensis is a commensal microorganism.

Skin infections due to S lugdunensis usually respond to antibiotic treatment.11 Unlike other CoNS, S lugdunensis is generally sensitive to penicillins owing to its low levels of beta-lactamase production, and less than 5% of isolates are resistant to oxacillin.5 In cases of simple skin abscesses, therapeutic guidelines recommend incision and drainage of the lesion; first-line antibiotic treatment is not indicated. In complicated cases, drainage and oral treatment with narrow-spectrum antibiotics such as cefadroxil, cephalexin, or cloxacillin is recommended. In cases of folliculitis, the drugs of choice are mupirocin and fusidic acid, combined with hygiene measures. In patients with extensive folliculitis, addition of an oral antibiotic (cefadroxil, cephalexin, or cloxacillin) is recommended.12 The most common treatment reported in the literature is topical antibiotic therapy, combined with oral antibiotics in more complicated cases.13

Because S lugdunensis colonizes the skin, it is important to determine when this microorganism becomes a pathogen. One of the cases in our series was a patient with T rubrum and C albicans coinfection who responded favorably to terbinafine. This is a clear example of S lugdunensis merely acting as a colonizing agent. Co-infection with E coli was detected in the 2 patients in which no treatment response was observed, suggesting that E coli, and not S lugdunensis, was the pathogen responsible for the infection. The pathogenic capacity of S lugdunensis in osteoarticular infections has been corroborated prospectively.14 However, caution is advised when interpreting single positive samples from skin or subcutaneous tissue or from known niches of this CoNS.15

S lugdunensis infection that responded well to antibiotic treatment has been described in a patient with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis who was being treated with adalimumab and methotrexate.16 In our series, 2 of the patients who experienced lesion recurrence were being treated with an anti-TNF agent, specifically adalimumab. One of the patients switched to adalimumab after showing a poor response to antibiotic treatment. Skin infection is one of the most frequently reported side effects of anti-TNF drugs.17 This is because TNF-α is a pro-inflammatory cytosine that plays an important role in innate immunity, and therefore its inhibition can increase the risk of infections, especially those of bacterial origin.18

S lugdunensis can be easily identified in the laboratory, provided that its possible presence is taken into consideration. Incubation on blood agar for 18 to 24 hours gives rise to colonies with weak β-hemolysis, which increases after 48 hours (Fig. 1B). Two tests are required to identify this bacterium: the ODC and PYR tests. Both are positive in the case of S lugdunensis, unlike other CoNS. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) provides a rapid and cost-effective means of identifying S lugdunensis.19 It has a sensitivity and specificity close to 100% for the identification of CoNS, especially S lugdunensis.20 The present series was performed before the recent acquisition of a MALDI-TOF system by our hospital.

The destructive nature of S lugdunensis, its great virulence, and its ability to cause suppurative infections more than justify active surveillance for this microorganism. In the past S lugdunensis was occasionally identified as a causal agent of human pathology, but is now detected with increasing frequency. This may be due to better understanding of its microbiological characteristics, a higher index of clinical suspicion, and the use of MALDI-TOF, which has enabled characterization of numerous CoNS species that were previously identified simply as coagulase-negative staphylococci or Staphylococcus species.5

S lugdunensis can be considered a pathogenic microorganism of skin in certain circumstances, depending on the clinical picture and affected location, and in patients with systemic or local risk factors, such as those in our series who were treated with anti-TNF agents.

FundingThis study did not receive specific funding from any public sector, private sector, or nonprofit entities.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: García-Malinis AJ, Milagro A, Torres Sopena L, Gilaberte Y. Infección cutánea por Staphylococcus lugdunensis: presentación de 16 casos. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021;112:261–265.