Carbamazepine (CBZ) is a tricyclic derivative of iminostilbene, marketed in 1962 for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia and, years later, as an antiepileptic and as a pillar of the treatment of bipolar disorder. Cutaneous adverse effects associated with the use of this drug were first described in 1967.1 The first 3 cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis linked to its use were published in 19822 and the first case of exfoliative dermatitis, studied using epicutaneous tests, was published in 1985.3 Since the drug was first used, different forms of skin toxicity have been described, although no case of acquired keratoderma has been reported to date.

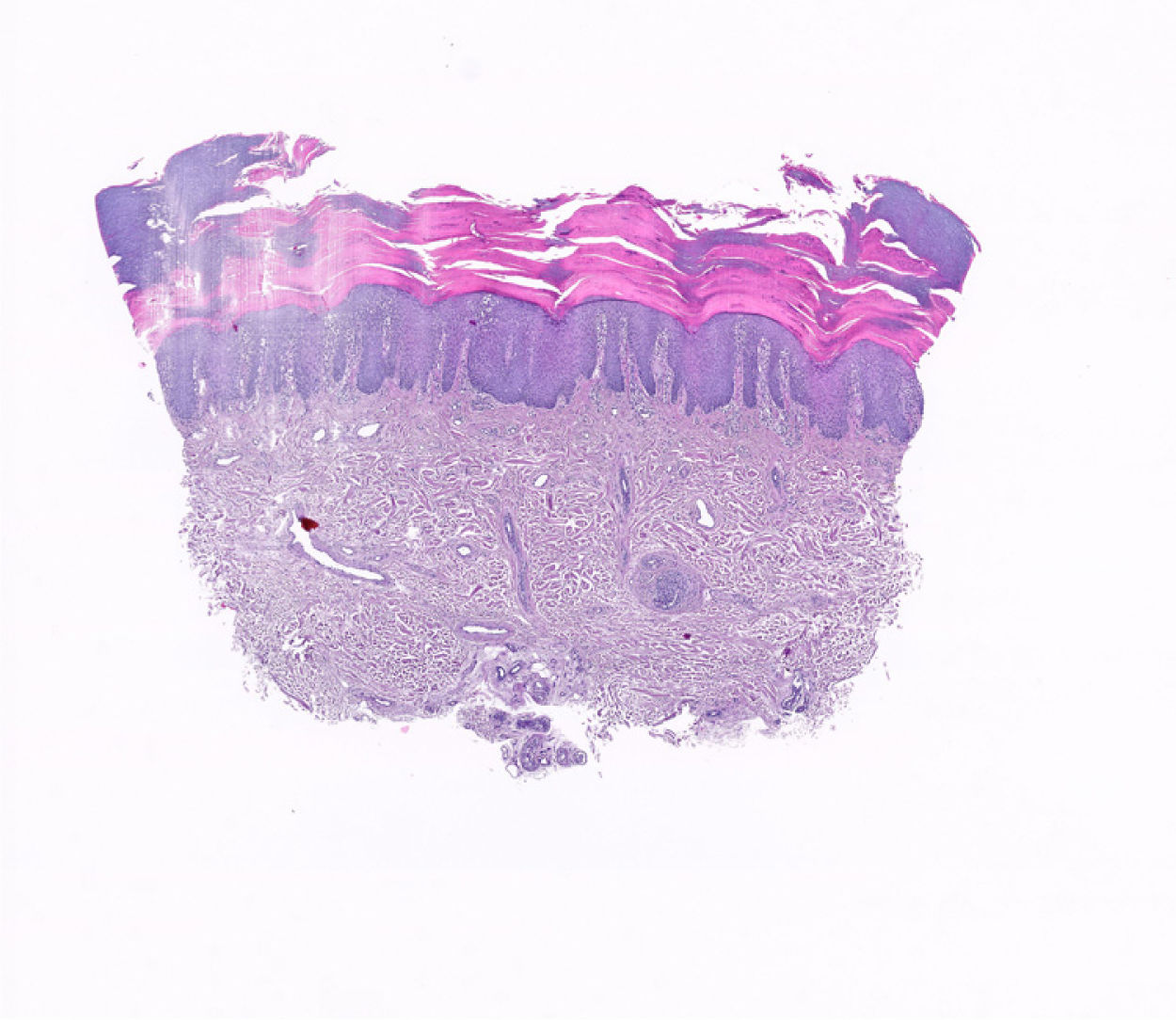

A 65-year-old man with no relevant personal or family history was assessed at our department for the gradual appearance of lesions on the palms of both hands, 2 weeks after starting treatment with CBZ at a dosage of 200mg every 12h for trigeminal neuralgia, which had recently been diagnosed in the neurology department. The physical examination revealed multifocal hyperkeratotic plaques on both hands (Fig. 1A–D); the lesions were asymptomatic with well-defined margins and did not coalesce. No involvement of the mucosa or soles of the feet was observed. Additional tests, including a blood count, general biochemistry, acute-phase reactants (PCR, VSG), and serology for syphilis, were normal. The patient reported no recent vaccines. Histopathology (Fig. 2) was compatible with keratoderma with no associated inflammatory process. The drug was suspended and replaced with one of a different therapeutic class to manage the patient's neurologic condition. The skin lesions were treated with topical emollients. Follow-up at 4 weeks showed complete clearance of the lesions.

A, Multifocal noncoalescing hyperkeratotic plaques on the palm of the left hand. B, Multiple hyperkeratotic plaques with well-defined edges on the palm of the left hand. C, Multifocal noncoalescing hyperkeratotic plaques on the palm of the right hand. D, Multiple hyperkeratotic plaques with well-defined edges on the palm of the right hand.

Different forms of skin toxicity have been described in relation to CBZ. Less severe signs and symptoms, such as lichenoid rashes,4 mycosis fungoides-like lesions,5 linear IgA bullous dermatosis,6 acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis,7 lichen planus,8 neutrophilic eccrine hydradenitis,9 erythema multiforme,10 vasculitis,11 and more severe skin toxicity, such as toxic epidermal necrolysis, Steven-Johnson syndrome,12 and DRESS syndrome.13 To date, we have found no cases of keratoderma secondary to use of this drug in the literature.

Several studies have recently been published that describe the cutaneous adverse effects caused by CBZ and their link to HLA.14,15 The association between HLA-B alleles (B*15:02 and B58:01) and the maculopapular exanthema it causes has been reported. Furthermore, the alleles HLA-B*15:02 and HLA-B*15:21 have shown a strong association with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis due to CBZ, whereas DRESS induced by CBZ has shown a significant association with the HLA-B*58:01 allele.

More recent studies have also provided data on the genetic factors that predispose to different phenotypes of adverse reactions to CBZ with important immune pathophysiology. CBZ causes hypersensitivity reactions mediated by T cells (CBZ-HR), including severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCAR) and liver damage (CBZ-DILI) associated with HLA-A*31:01.16

Keratoderma includes a broad group of dermatoses that may be congenital or acquired. To differentiate between the 2 groups, it is necessary to take into account the age of presentation of the lesions and a positive family history leading to suspicion of the hereditary component. With regard to dermatoses of acquired origin, drug-related iatrogenesis is the most frequent cause, including verapamil, lithium, venlafaxine, and quinacrine. We should also take into account their expression as a paraneoplastic manifestation of lung, breast, bladder, or digestive cancer (tripe palms).

Treatment of acquired keratoderma secondary to drugs requires first suspending (whenever possible) the suspected drug. In patients with symptomatic keratoderma or keratoderma that affects quality of life, topical keratolytic agents, oral retinoids, or phototherapy may favor and accelerate resolution of the hyperkeratotic lesions.

It is important to remember that patients who are due to be treated with carbamazepine may develop hypersensitivity to the drug. To prevent this severe drug toxicity, screening for HLA-B1502, HLA-B*58:01, and HLA-A31:01 is recommended before instating treatment, principally in patients of Asian descent.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.