This is the case of a 15-year-old boy who presented with a 2-month history black mark on his forehead, which has progressively darkened ever since. Both his past medical and family histories were unremarkable. There was no history of vaccination, or drug use before the lesion appeared.

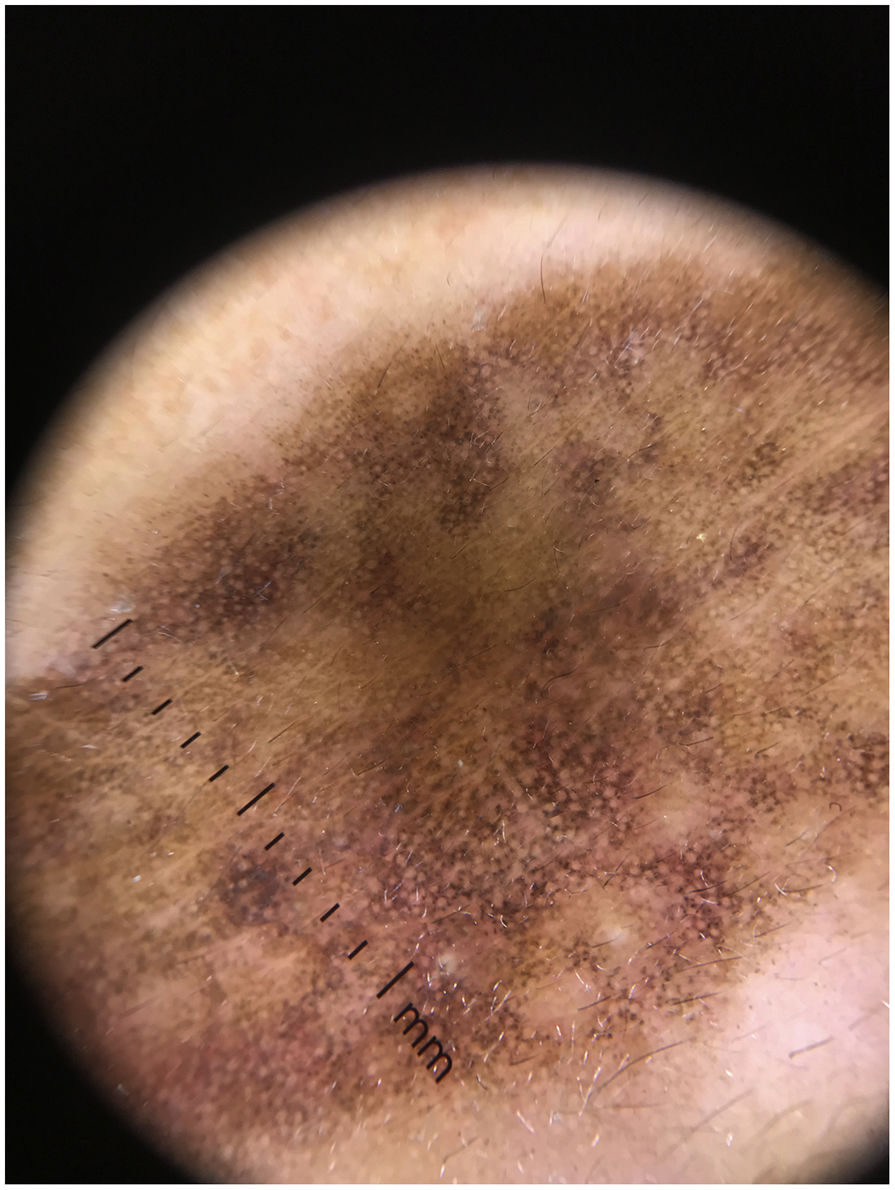

Physical examinationThe physical examination revealed the presence of a diffuse grayish-brown patch lesion on the forehead (Fig. 1 A). The dermoscopy performed (DermLite DL4; 3Gen; polarized, 10×) revealed the presence of an exaggerated pseudoreticular network with light and darker brown dots in linear, peppering/nonspecific, reticular, and incomplete reticular arrangements. Fewer grayish globules presented as nonspecific, along with polygonal patterns. In some areas, there were blotch structures which larger globules obscuring the eccrine openings. There is also presence of blue-gray annular granular structures in the peri-eccrine regions (Fig. 2). Differential diagnosis of lichen planus pigmentosus, granuloma annulare, discoid lupus erythematosus and fixed drug eruption was considered, which is why a punch biopsy was performed.

Exaggerated pseudoreticular network with light and darker brown dots in linear, peppering/nonspecific, reticular, and incomplete reticular arrangements. Fewer grayish globules seen as nonspecific and polygonal patterns. In some areas, blotch structures could be seen. Lastly, blue-gray annular granular structures could be seen in peri-eccrine areas.

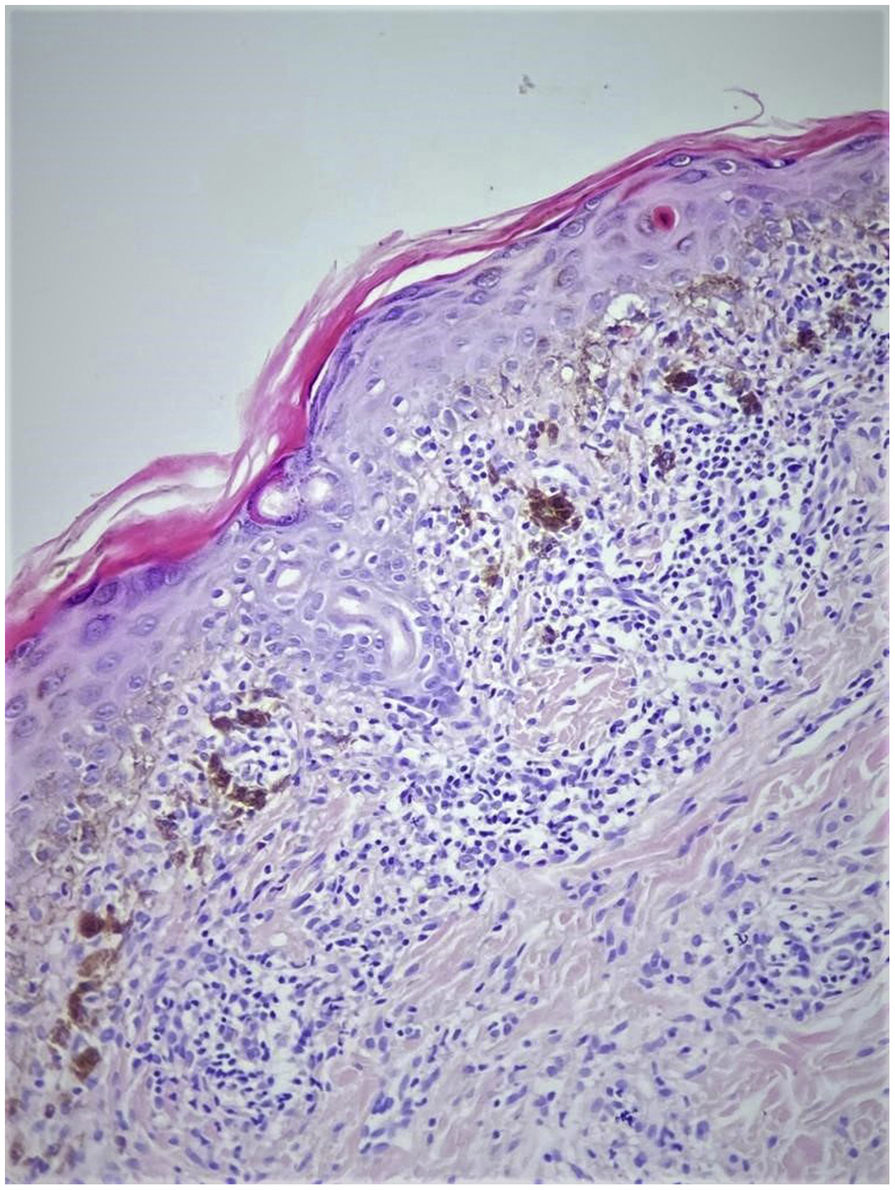

Histopathologically, an increased granular cell layer in the epidermis, hydropic degeneration and necrotic keratinocytes were seen in the basal cell layer. There was lichenoid lymphocytic infiltration and diffuse pigment incontinence in the dermis (Fig. 3).

What is your diagnosis?

DiagnosisThe patient was diagnosed with lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP).

Clinical course and treatmentThe patient was treated with acitretin 10mg/day, Kligman's formula, and sunscreen, and patient followed for 12 months. The color of the lesion faded significantly (Fig. 1B) and acitretin treatment was discontinued. The patient is still on Kligman's formula and being properly monitored.

CommentLPP is clinically characterized by discrete macules and patches of dark brown or slate-gray color, mostly seen in skin types IV–VI. Overall, it has been reported in patients from India, Latin America, Asia, and Africa, but it is quite rare in Caucasians suggesting a genetic susceptibility. It is most common in patients between the ages of 30 and 50.1

LPP is very rare in children. In a study of 316 children diagnosed with LP, LPP was reported in 9 children only (2.8%). In any case, only 1–4% of all the cases of LP reported are pediatric LP.2 Therefore, since LP per se is a rare condition in children, it is not surprising that its rare subtype LPP is an extremely rare condition in children.

LPP is often seen in sun-exposed areas, especially the face and the neck. Pigmentation may be diffuse, reticular, blotchy, linear, or perifollicular, with the diffuse type being the most common of all. Atypical presentations include involvement of areas not exposed to the sunlight (LPP inversus), flexural, linear, and segmental, or zosteriform lesions.3

Sharma et al. evaluated the facial lesions of 50 patients with LPP dermoscopically.4 The most common dermoscopic finding was dots and/or globules (43/50, 86%) in different patterns: hem-like (20.9%), arcuate (18.6%), incomplete reticular (39.5%), complete reticular (7%), and not otherwise specified (14%). Other patterns were exaggerated pseudoreticular pattern, accentuation of pigmentation around follicular openings, targetoid appearance, and obliteration of the pigmentary network.

Pirmez et al.5 described 4 different dermoscopic patterns of pigmentation in LPP: pseudonetwork in 64% of the cases, speckled (irregularly arranged) dots in 35%, uniform dotted in 22%, and circular dots in 19% with overlapping patterns in 38% of the cases.

Topical treatment includes medium to high potency corticosteroids, tacrolimus, and depigmenting agents such as 4% hydroquinone, Kojic acid, modified Kligman's formula (tretinoin at 0.025–0.05%, hydroquinone at 4%, and dexamethasone at 0.1%). Systemic treatment modalities have also been tried including systemic corticosteroids, vitamin A, and dapsone. Since the clearance of the lesion is often incomplete, the use of lasers or their combination with topical agents can be considered.6

In conclusion, dermoscopy is a very useful non-invasive technique in cases with hyperpigmentation and melanocytic lesions. We presented this case because it is a rare pediatric case that can be mistaken for many hyperpigmented acquired conditions. LPP should be considered in the differential diagnosis of hyperpigmented patches in children, especially in sun-exposed areas.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.