Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is the most useful tool for node staging in melanoma. SLNB facilitates selective dissection of lymph nodes, that is, the performance of lymphadenectomy only in patients with sentinel nodes positive for metastasis. Our aim was to assess the cost of SLNB, given that this procedure has become the standard of care for patients with melanoma and must be performed whenever patients are to be enrolled in clinical trials. Furthermore, the literature on the economic impact of SLNB in Spain is scarce.

MethodFrom 2007 to 2010, we prospectively collected data for 100 patients undergoing SLNB followed by transhilar bivalving and multiple-level sectioning of the node for histology. Our estimation of the cost of the technique was based on official pricing and fee schedules for the Spanish region of Murcia.

ResultsThe rate of node-positive cases in our series was 20%, and the mean number of nodes biopsied was 1.96; 44% of the patients in the series had thin melanomas. The total cost was estimated at between €9486.57 and €10471.29. Histopathology accounted for a considerable portion of the cost (€5769.36).

DiscussionThe cost of SLNB is high, consistent with amounts described for a US setting. Optimal use of SLNB will come with the increasingly appropriate selection of patients who should undergo the procedure and the standardization of a protocol for histopathologic evaluation that is both sensitive and easy to perform.

La técnica de la biopsia selectiva del ganglio centinela (BSGC) es la mejor herramienta para la estadificación ganglionar en el melanoma, permitiendo la realización de una linfadenectomía selectiva, es decir, reservada solo a aquellos pacientes que muestran el GC positivo para metástasis. Nuestro objetivo fue evaluar el coste económico de la técnica de la BSGC, ya que se ha convertido en el procedimiento recomendado como estándar en la atención al paciente con melanoma, y es necesaria para la inclusión de los pacientes en los ensayos clínicos. Existe además escasa bibliografía en nuestro medio sobre su relevancia económica.

MétodoDe forma prospectiva se recogieron 100 pacientes a los que se realizó la técnica entre los años 2007-2010 con un procesamiento histológico transhiliar bivalvo multisecciones. Realizamos un cálculo aproximado del precio de la técnica utilizando las tarifas de precios oficiales de la Región de Murcia.

ResultadosEl porcentaje de positividad de nuestra serie fue del 20%, con un número medio de ganglios de 1,96 y un 44% de melanomas delgados. El precio total de la técnica es de 9.486,57-10.471,29 euros, siendo una parte muy importante de la misma atribuible al procesamiento histopatológico (5.769,36 euros).

DiscusiónLa técnica de la BSGC tiene un precio muy considerable, aunque en consonancia con otras referencias americanas previamente descritas. La optimización de la técnica vendrá dada en función de la selección cada vez más adecuada de los pacientes que deben someterse a ella, y a la estandarización de un modelo histopatológico sensible en la detección, pero a la vez sencillo en el procesamiento.

The optimal node staging approach in melanoma is based on sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), which serves as a guide for selective lymphadenectomy performed in node-positive cases.1 Guidelines for referring patients for SLNB are constantly changing. In general, biopsy is recommended in cases of primary melanoma without evidence of regional or distant metastasis when the risk of node metastasis is at least 10%, which is to say clinical stages IB and IIA, B, and C according to the 7th edition of the staging manual of the American Joint Committee on Cancer. Selection criteria have not yet been standardized for cases with a Breslow thickness of less than 0.75mm, but defining a treatment approach for this subgroup of patients will become crucial given that they now account for 60% to 70% of melanomas diagnosed in large hospitals.2,3 This group has grown more rapidly than others in recent years.

A lower threshold for significant node metastasis has not yet been established; thus, a finding of a single isolated melanoma cell in the sentinel node would be sufficient grounds for a positive classification and, therefore, would lead to a change in therapeutic approach. Given that the most recent melanoma guidelines of the American Joint Committee on Cancer4 stipulate that identifying a single melanoma cell should be the goal, histologic processing of the biopsied material should be as exhaustive as possible. As processing is inevitably incomplete, however, finding single cells will be largely a matter of chance.

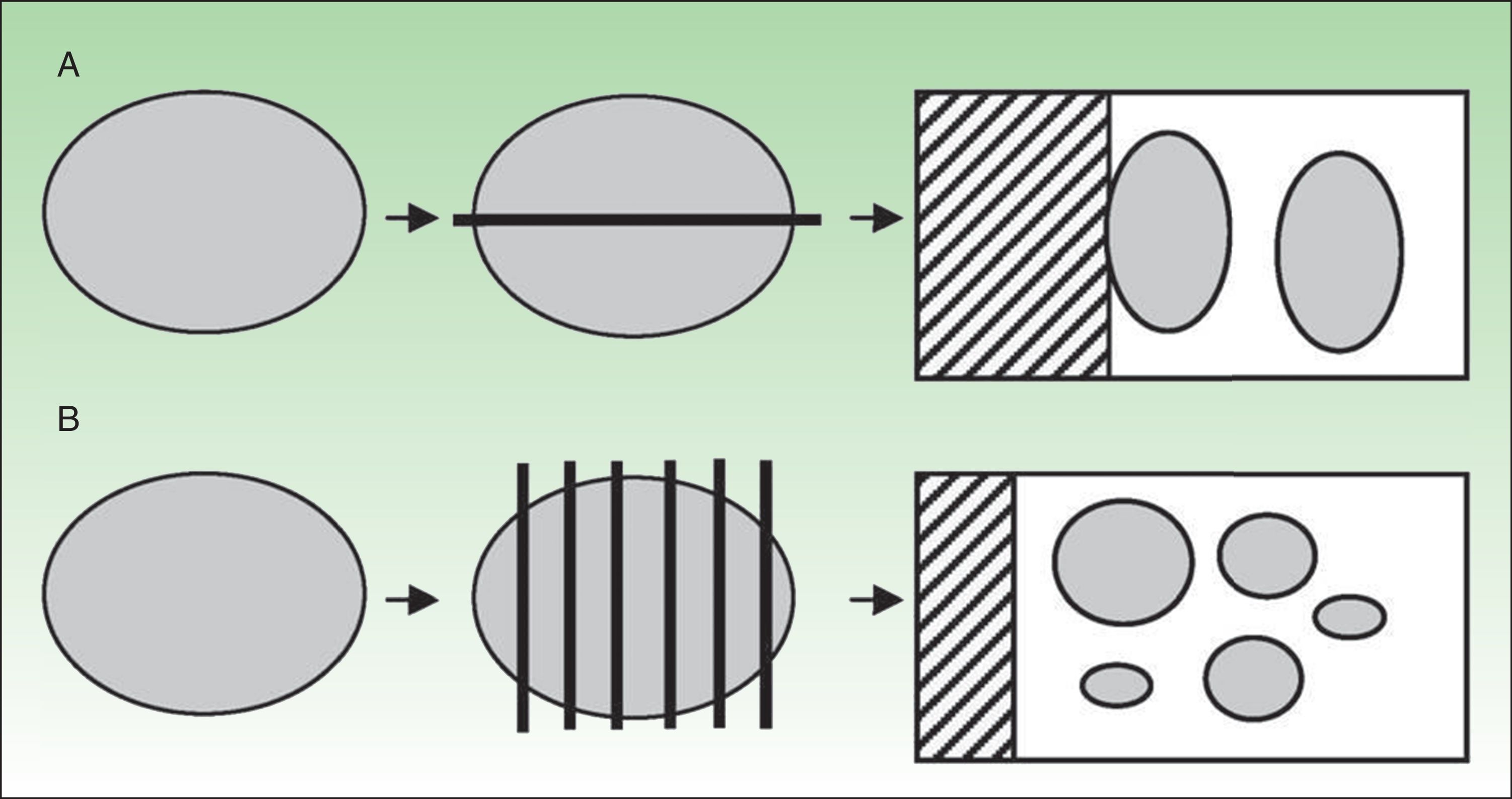

Clear standardization of an approach to histologic processing of the sentinel node is also lacking, though transhilar bivalving and examination of parallel slices (breadloafing) (Fig. 1) are techniques that have received attention.5,6

Our principal aim was to assess the cost of SLNB in our practice setting, a referral hospital for the Spanish region of Murcia, given that this procedure has become the standard of care for patients with melanoma and is also necessary whenever patients are to be enrolled in clinical trials. Few cost studies have been done in Spain, however, and our view is that the economic impact of SLNB has been underestimated. A prospective observational study was therefore designed to estimate SLNB-related costs in our hospital.

Material and MethodsInformation for 100 patients undergoing SLNB in the period from 2007 to 2010 was recorded in a database. A standardized transhilar bivalving technique was used in all cases. The inclusion criteria were as follows: primary cutaneous melanoma with a Breslow thickness of at least 1mm or 0.75mm if there were concurrent signs associated with greater likelihood of node positivity (i.e., ulceration, regression, age under 40 years, or lymph vessel invasion). Melanomas in pediatric patients were excluded because the natural history of these tumors differs in adults and children.

The study was carried out in the dermatology department of Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca, which is the referral hospital for SLNB. The hospital's catchment area has approximately 560 000 inhabitants.

SLNB TechniqueWe injected a technetium-99 radiolabeled tracer (Lymphoscint, Amersham, Saluggia, Italy) with colloid particles 50 to 100nm in diameter. The amount of solution was 1mL, distributed in 4 intradermal injections of 250μCi, each containing 1μCi (37MBq) of the tracer. The injections were made around the lesion (or around the scar in the case of previously excised lesions closed by direct suture without flaps or graft reconstructions). A tracer uptake time of 2 to 4hours was allowed before the procedure. After the gamma-camera guided injections, sequential and dynamic images were recorded every 10seconds for 5minutes. Immediately afterwards, a static image of a single projection was recorded for 180seconds (matrix, 256×256 pixels). We considered the gamma camera to be correctly placed if 1 or more draining nodes could be identified; the first such nodes that appeared were considered sentinel nodes and their locations were marked. If nodes were not found, another acquisition was attempted an hour later; yet another attempt 2hours later might also be made. If a sentinel or other draining mode was adequately located it was biopsied in the operating room, with the aid of images from the preoperative lymphoscintigram and guidance from a handheld gamma probe. To minimize damage to the node, the biopsy was harvested with Babcock forceps, and diathermy for hemostasis was used cautiously.

Histologic ProcessingThe processing protocol included transhilar bivalving of the node and multiple-level parallel sectioning. The sentinel nodes were fixed in formalin for 24hours and then embedded in paraffin. Five serial sections of 5μ each were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (2 slices) for histology; immunohistostaining with antibodies for S100, HMB-45, and Melan-A completed the processing of these zero-level studies. Then, 250μ was sliced into 5 additional sections for histologic and immunohistochemical staining of another level. This process of step-sectioning the material was repeated at intervals of 250μ. Each node was approximately 4mm in diameter so on average, 9 levels could be studied once the bivalved node had been placed in cassettes for paraffin embedding. As described above, the sections sliced from each level were processed with H&E, anti-Melan-A, anti-S100, and anti-HMB-45 staining to give an average of 45 processed sections for the pathologist to evaluate in total (in levels corresponding to 0, 250, 500, 750, 1000, 1250, 1500, 1750, and 2000 μ) (Fig. 2).

Fee and Price ScheduleOur cost study was based on unit prices found in the fee and price schedule published in the regional government's official gazette (Boletín Oficial de la Región de Murcia, February 2013). Our hospital's accounting and analysis department did not make available their data on actual spending. The published prices are used by the hospital to invoice third parties and are approximate indications of real costs. Both direct and indirect costs were included, such that staffing and maintenance of the facilities were reflected. There is no unit price specified for whole the set of services related to SLNB in the diagnosis of melanoma; we therefore added up the costs for each of the component procedures performed in the process.

ResultsOf a total of 100 patients diagnosed with melanoma who underwent SLNB from 2007 to 2010, all inclusion criteria were met by 99 patients, whose data entered the analysis.

The mean Breslow thickness was 2.02mm (median, 1mm); 20% of the cases were node-positive. A mean (SD) of 1.96 (1.46) nodes (95% CI, 0.50–3.42 nodes) were excised per patient (median, 1); for cost estimates, the mean was rounded up to 2. Table 1 shows descriptive data for the series. The Breslow thickness was less than 1mm in 44 (44%) patients; 1 of these patients (2.2% of the 44) had a positive node.

Main Characteristics of the Patient Series.

| Variables | 2007–2010 Series |

|---|---|

| Mean Breslow thickness, mm | 2.02 |

| Sex | |

| Men | 41 (41.41%) |

| Women | 58 (58.58%) |

| Location | |

| Limbs | 42 (42.85%) |

| Trunk | 49 (50%) |

| Head and neck | 7 (7.15%) |

| Findings of histopathology | |

| Negative | 79 (79.79%) |

| Positive | 20 (20.20%) |

| Isolated cells | 4 (4.04%) |

| Micrometastasis | 3 (3.03%) |

| Macrometastasis | 13 (13.13%) |

| No. of nodes excised | |

| 1 | 51 (51.51%) |

| 2 | 28 (28.28%) |

| ≥3 | 20 (20.20%) |

The hospital's fees for the various procedures required for SLNB are shown in Table 2.

General Costs Necessary for SLNB, Excluding Histopathologic Processing Costs.

| Item | Cost, € |

|---|---|

| Conventional hospitalization per day; price code, A.1.3 | 583.60 |

| Radical excision of skin lesion (with safety margins), ICD-9-CM.86.40 | 1726.28 |

| Skin graft or flap, ICD-9-CM.86.60 | 1726.28 |

| Nuclear medicine study, sentinel node in melanoma; price code, A.5.1.N.8 | 200.38 |

| Axillary lymph node excision, ICD-9-CM.40.23 | 1206.95 |

| Inguinal lymph node excision, ICD-9-CM.40.24 | 2191.67 |

Abbreviations: ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Accordingly, the total cost of biopsying an axillary node was €3717.21; the cost was €4701.93 for an inguinal node. If more than 1 drainage pathway was identified, costs increased.

Histopathologic processing of multiple-level sections amounted to approximately €2884.68 in this hospital series (Table 3). Given that our hospital biopsied 2 nodes per case on average, the price of histopathologic processing came to €5769.36 per case. The total cost of SLNB therefore ranged from €9486.57 to €10 471.29.

DiscussionThis study found that SLNB-related costs ranged between €9486.57 and €10 471.29 in this prospectively enrolled series of 99 patients treated in our referral hospital in the Spanish region of Murcia.

As a basis for comparison with other procedures performed in the hospital, we mention that the unit prices for kidney and liver transplants are €27 327.71 and €92 581.04, respectively, indicating that the cost of SLNB is by no means negligible.

Our hospital has been performing SLNB for approximately 20 years. The multidisciplinary team responsible for the procedure is comprised of members of the dermatology, general surgery, nuclear medicine, and pathology departments. An operating room for major outpatient surgery is used, and patients are usually hospitalized for 1 day. As no immediate postoperative complications that prolonged hospitalization developed in this series, all patients were discharged the next day.

The costs we calculated are consistent with the range of $10 000 to $15 000 (€7620 to €11 431) reported earlier by a US hospital.7

Only one other study in Spain has analyzed the costs of the various steps in the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous melanoma.8 The authors of that study estimated the general costs of SLNB to be €682.24 (with 1 day of hospitalization and re-excision of the melanoma scar with margins of 2cm), but they did not describe the process they used for sentinel-node histology.

A cost-effectiveness study in Australia by Morton et al.9 estimated that their procedure (without study of safety margins) cost €1902.45. We point out that the approach to histologic processing was not detailed in that study either, even though this component of SLNB is responsible for higher costs.

Our results show that histologic processing accounts for a large portion of the cost of SLNB. Many processing approaches have been used, and their ability to detect positive nodes depends on how exhaustively the material is assessed. Examination of parallel slices (breadloafing) must be distinguished from transhilar bivalving approaches (Table 4). The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer currently recommends that the sentinel node be examined with the histopathologic method described by Cook et al.5 This approach relies on transhilar bivalving and assessment of material in step sections of 50μ. At each step, or processing level, 4 slices are cut and prepared with H&E, anti-S100, anti-HMB-45, and Pan Melanoma Plus stains. Some material is left unstained in case the node must be reassessed. This protocol examines about 700to 800μ, not the entire node. In fact, the recommended method is neither rapid nor easy to standardize, and it generates costs that many hospitals are unable to absorb. Findings from a study by Bastistatou et al.,10 based on a telephone survey of dermatopathologists who were members of the European Society of Pathology, illustrated these problems: only 48% of the respondents used transhilar bivalving and only 42% used a method of parallel slicing. The respondents examined from 1 to 20 steps. The most complete processing approach involves multiple slices for histology and the use of immunohistochemical stains that add considerably to the overall expense. Our current approach to assessing the sentinel node follows the guidelines for treating melanoma in the region of Murcia11; very similar guidelines are used in Valencia.12

Summary of Approaches to Assessment of the Sentinel Nodea

| Authorb | Processing Technique | Multiple-Level Sectioning | No. of Sections | Staining | % c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spanknebel (routine pathology) | Transhilar bivalving | 1 level | 1 frozen, 1 paraffin-embedded | H&E | 20 |

| Spanknebel (extended pathology) | Transhilar bivalving | 20 levels, every 50μ | 60 | H&E, anti-S100, anti-HMB-45 | 61 |

| Cook (protocol 1) | Transhilar bivalving | Not done | 8 | H&E, anti-S100, anti-HMB-45 | 18 |

| Cook (protocol 2) | Transhilar bivalving | 2 levels, every 50μ | 12 | H&E, anti-S100, anti-HMB-45 | 25 |

| Cook (protocol 3) | Transhilar bivalving | 5 levels, every 50μ | 20 | H&E, anti-S100, anti-HMB-45, Pan Melanoma Plus | 34 |

| Abrahamsen | Transhilar bivalving | Every 250μ (entire node) | According to size of node | H&E, anti-S100, anti-HMB-45, anti-Melan-A | 28 |

| Bostick, Takeuchi | Transhilar bivalving | 80μ frozen+3 levels every 40μ | 4–16 | H&E, anti-S100, anti-HMB-45 | 24 |

| Starz | Parallel to the longitudinal axis | 1mm, with scalpel | According to size of node | H&E, anti-S100, anti-HMB-45 | 38 |

| Li | 1 level | 4 | H&E, anti-S100, anti-HMB-45 | 15 | |

| Rimoldi | Parallel to the shortest diameter | 2–3mm, with scalpel | 12–20 | H&E, anti-S100, anti-HMB-45, anti-tyrosinase, anti-Melan-A | 24 |

Abbreviation: H&E, hematoxylin and eosin.

How long the pathologist takes to assess all the slices should also be taken into consideration. We estimated assessment took 2minutes per slice on average; thus if 36to 45 are to be assessed, a pathologist will spend at least 72minutes on a single node. As a case involves 2nodes on average, 144minutes of a pathologist's time will be required for each patient undergoing SLNB.

The use of this technique should be as restricted as possible. In a case with a low Breslow index, SLNB may be justified when the likelihood of node positivity is at least 10%, but the procedure is currently being ordered by clinicians even when risk of positivity is lower. Furthermore, the overall survival rates for patients with thin melanomas are excellent, ranging from 85%to 99%, and patients with melanomas less than 1mm thick are becoming the largest group (accounting for 60% to 70% of new diagnoses in large hospitals). Forty-four percent of our patients who underwent SLNB had tumors with a Breslow thickness of less than 1mm, and in that group only 1 patient (2.2%) had a positive node.

Thus, 43 node-negative SLNBs and 1 node-positive SLNB were performed in this subgroup. Given that SLNB ranges in cost from €9486.57 to €10 471.29, the cost of detecting a single positive node in the group of patients with melanomas less than 1mm thick was between €417 409.08 and €460 736.76 in our series. Patients were enrolled in this study over a 3-year period, suggesting an incidence of 0.33 node-positive cases per year. Thus, the estimated annual cost would have been €137 744.97 to €152 043.13.

If pathologic assessment were extended only to the melanoma excision scar, the cost would have been €1791.41; multiplied by 44 patients the total would be €78 822.04.

Therefore, SLNB leads to a total cost increase of €338 587.04 to €381 914.72; per patient, the increase attributable to SLNB would be €7695.16 to €8679.88.

Agnese et al.7 calculated a loss of 17.1 years of life per melanoma. Dividing the increased cost generated by SLNB by the loss of potentially lost years of life suggests an estimated cost of €19 800.40 to €22 334.19 for each year of life saved. The literature suggests a figure of approximately $35 000 (about €27 000) as the upper limit considered reasonable to spend on SLNB per life saved.13,14 This purely economic indicator is very difficult to evaluate, but in theory the amounts we calculated suggest that our costs fall within the recommended limits.

Our method for calculating the cost per year of life saved was based on the approach of Agnese et al.,7 who estimated the cost to be €43 156.26 in a series of 99 melanomas with a Breslow thickness less than 1mm. This figure was higher than in our study, and the authors had to assess 91 cases to find a single positive node. They concluded that SLNB does not appear to be cost-effective and that it should be questioned in cases of thin melanomas.

Our cost-effectiveness data suggest that the selection of patients for SLNB should be improved, especially in thin tumors (Breslow thickness less than 1mm), given that the procedure is costly and, in our practice setting, the diagnostic yield is low in this subgroup of patients. These concerns are important at this time because new approaches to treatment for metastatic melanoma could be useful adjuncts to therapy in the near future.15 It is therefore crucial to be able to identify melanomas that have reached the node, so that such new treatments could be offered if necessary.

Optimal use of SLNB should be based on improving patient selection and standardizing the histopathologic processing protocol to establish one that is sensitive but also simple. Optimization is a dynamic process and is being intensely debated at this time. Studies in larger cohorts will be required so that conclusions can be based on more data.

This study analyzed the costs of SLNB in our hospital. Even though further analyses are needed, our calculations give some indication of what is being spent. Our data can serve to raise awareness of economic issues related to the use of SLNB in teams carrying out the procedure.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Data confidentiality. The authors declare that no private patient data are disclosed in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no private patient data are disclosed in this article.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Martínez-Menchón T, Sánchez-Pedreño P, Martínez-Escribano J, Corbalán-Vélez R, Martínez-Barba E. Evaluación del coste económico de la técnica de la biopsia selectiva del ganglio centinela en melanoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:201–207.