We now realize that moderate to severe psoriasis takes a toll on the patient's overall health beyond the effects on the skin itself, and so we use quality of life (QOL) measures to assess how the individual perceives both the impact of disease and the response to treatment. However, available instruments give us a cross-sectional assessment of QOL at a specific moment, and we lack longitudinal studies of how a disease affects each and every aspect of a patient's life over time–including physical and psychological wellbeing, social and emotional relationships, vocational and employment decisions and how they change the individual's outlook. A new concept, cumulative life course impairment (CLCI), captures the notion of the ongoing effect of a disease, providing us with a new paradigm for assessing the impact of psoriasis on QOL. Unlike conventional measurement tools and scales, which focus on a specific moment in the patient's life, a CLCI tool investigates the repercussions of disease that accumulate over a lifetime, interfering with the individual's full potential development and altering perspectives that might have been different had psoriasis not been present. The accumulated impact will vary from patient to patient depending on circumstances that interact differently over time as the burden of stigmatization, concomitant physical and psychological conditions associated with psoriasis, coping mechanisms, and external factors come into play and are modulated by the individual's personality.

Hoy en día se acepta que la psoriasis moderada-grave repercute de forma global en la salud del individuo mucho más allá de la clínica cutánea, y se emplean medidas de calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (QoL) para evaluar tanto la afectación percibida por el paciente como la respuesta de la misma al tratamiento. Sin embargo, las medidas de QoL disponibles se refieren a un momento o período concreto de la vida del paciente, de forma transversal, y no disponemos de estudios longitudinales que evalúen en qué medida el impacto de la enfermedad va condicionando todas y cada una de las vertientes de la vida del paciente —bienestar físico, psicológico, relaciones sociales y emocionales, decisiones vocacionales y laborales, etc.– modificando sus perspectivas. Para referirnos este impacto continuado y acumulativo se ha introducido un nuevo concepto, que se conoce como discapacidad acumulada en el transcurso vital (Cumulative Life Course Impairment [CLCI]) y constituye un nuevo paradigma de evaluación del impacto de la psoriasis en la QoL del paciente. A diferencia de las medidas y escalas convencionales, que focalizan la evaluación en un momento o período concreto de la vida del paciente, de forma transversal, en el CLCI se tiene en cuenta el impacto acumulativo que la afectación provocada por la psoriasis tiene longitudinalmente a lo largo de la vida del paciente, interfiriendo con el máximo desarrollo potencial del paciente y con su perspectiva vital si la psoriasis no hubiese existido. El resultado final será distinto para cada paciente, en función de las circunstancias que interactúen en cada momento, derivadas de la interacción entre la carga de la estigmatización, las comorbilidades físicas y psicológicas asociadas a la enfermedad y de las estrategias de afrontamiento y los factores externos que puedan intervenir, modulados por los estilos de personalidad de cada paciente.

Psoriasis is a multifactorial disease with effects that go beyond the physical symptoms to compromise the patients’ psychological and emotional wellbeing. The physical and psychological impact of the condition, which has been a subject of study for some decades, extends into all areas of these patients’ lives, affecting both their personal lives—emotional wellbeing, relationships, sexuality, and leisure activities—and their relationships with others—work, social life, family, and financial status.1–10 To date, studies in this area have focused on quality of life (QOL), quantifying the impact of psoriasis using cross-sectional data—in many cases retrospective—to provide a profile of the disease burden at a specific point in the patient's life. What this method does not take into account is the progressive impairment these patients accumulate over the course of their lives.11,12 Recently, a new approach—called cumulative life course impairment (CLCI)—has been proposed as a way to take into account the cumulative effect of psoriasis and the way physical and psychological comorbidities and the stigma associated with the symptoms of the condition progressively affect the patient's life over time.

The concept of CLCI as described in this article arose from the work of an international committee of dermatologists, psychologists, and experts in psychometrics undertaken to develop a multidisciplinary approach to the management of psoriasis. The concept, which had already been applied in other disciplines, such as medical psychology and sociology, is based on analysis of the mechanisms and interconnections that influence the life course of patients who have a chronic disease and explores how protective factors and risk factors interact throughout the course of the disease. CLCI has been used in numerous chronic diseases.13–19 The ultimate goal of this approach is to achieve a better understanding of the overall cumulative impact of psoriasis, helping to identify individuals who are more vulnerable to this cumulative damage, and facilitating more appropriate treatment decisions tailored to the needs of each individual.11

The Concept of Cumulative Life Course ImpairmentThe concept of CLCI takes into account the cumulative impairment acquired by the psoriasis patient over a lifetime. The purpose of this concept, which has only recently been applied to the management of psoriasis, is to reflect the chronic nature and cumulative effects of the disease as well as the well-known repercussions, including stigmatization and numerous physical and psychological comorbidities. The concept of CLCI also incorporates other important components, factors that can play a moderating role or make the patient less vulnerable to such impairment. These include external factors (for example, a supportive environment), coping strategies, and personality style. The interaction between all these factors could explain the variations we observe between patients and how each individual experiences life with psoriasis.

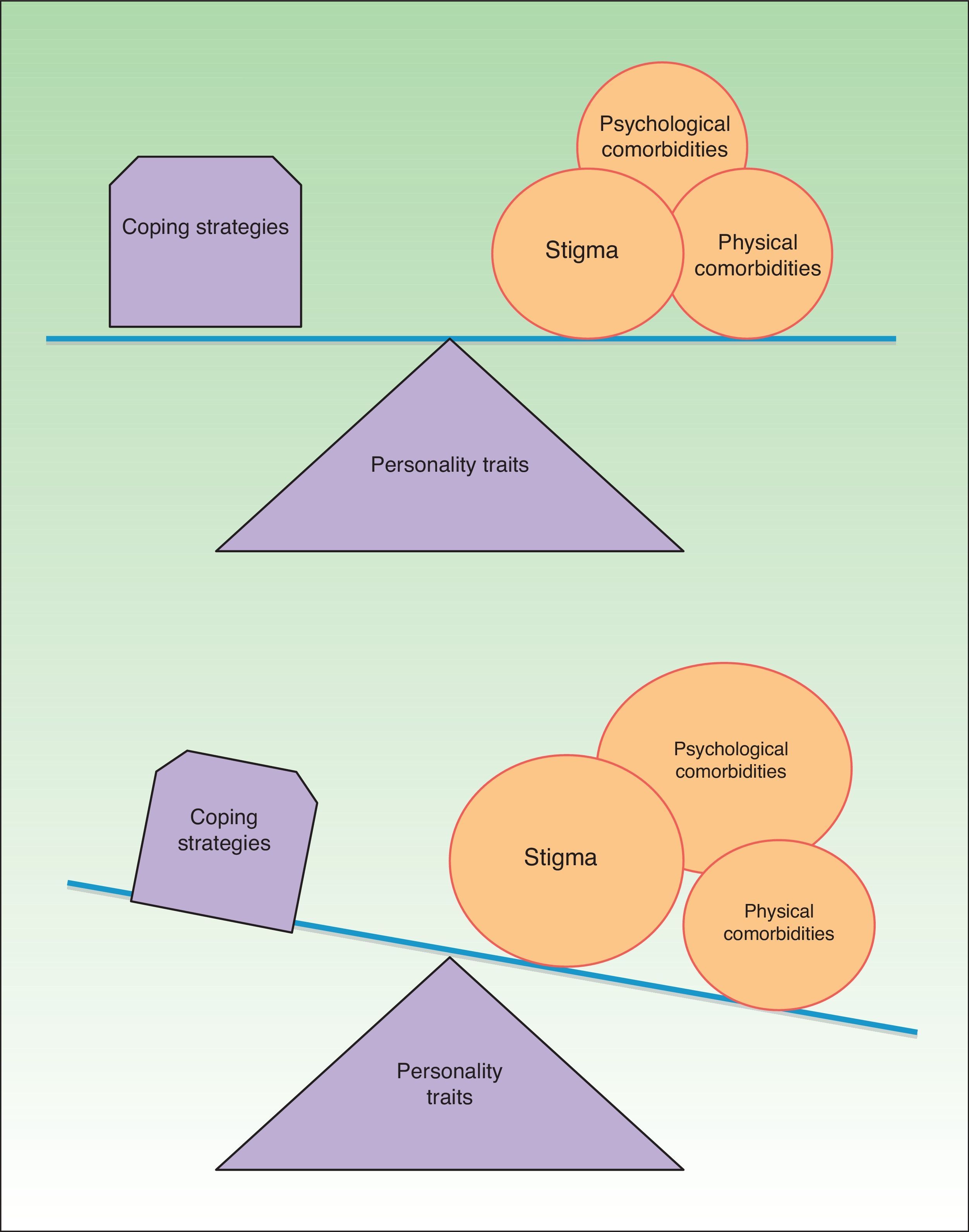

As illustrated in Fig. 1, CLCI is the cumulative result of the balance between (A) the burden of the physical and psychological comorbidities and stigma associated with psoriasis and (B) the external factors and coping strategies modulated by the patient's personality. The relative weight of each of these components in each individual explains the inconsistencies we see in how different patients experience psoriasis of similar severity. Assessment of these components can also help us to determine each patient's vulnerability to the impact and detrimental effect of the disease (Fig. 1).

The negative impact of this cumulative impairment on different areas of the patients’ lives is progressive and influences its course, undermining their aspirations and personal fulfillment and influencing major life-changing decisions that will mark their identity as well as their personal, professional, social, and family development. Patients with psoriasis believe that their lives would have been substantially different without the chronic and visible impact of the disease. This cumulative impairment over time can prevent patients from achieving their personal life goals and substantially alter the course of their lives. In such cases their life with psoriasis is different than what it might have been if they had not had the disease.12

The impact of a chronic disease on major life-changing decisions has been studied in a number of medical specialist fields, including cardiology, pulmonology (cystic fibrosis), endocrinology (diabetes), nephrology, and rheumatology.17–25 Bhatti et al.,22–24 who studied this aspect in the dermatological setting, have reported that patients with psoriasis believe that their condition has had an influence on major decisions. Some 66% reported that it influenced their choice of career, 58% their choice of work, 52% their personal relationships, 44% their education, 22% their decision about whether to have children, and 20% the decision to take early retirement.23–25

In any analysis of these results, it is important to bear in mind that most life-changing decisions—such as the choice of a college major or job or the decision to establish a couple or to have children—are made in adolescence and early adulthood.17,23 If the onset of psoriasis coincides with a critical period or a particularly vulnerable phase in the patient's life (adolescence or early adulthood) and a time when major life-changing decisions are taken, the impairment caused by psoriasis will be more likely to influence these decisions and the patient will be at higher risk for CLCI. Patients who develop psoriasis later in life, between the ages of 40 and 50, tend to be less vulnerable because at this stage in their lives they have already made these major decisions.23–26

One question that arises in any discussion of CLCI is the difference between this concept and the more well-known concept of QOL. The answer lies in the individual dynamic and holistic complexity of each patient. While QOL tools assess the patient's life at a single point in time or over a specific period, the aim of CLCI is to go beyond this limitation: using a broad and holistic perspective, CLCI investigates the progressive, cumulative nature of the often irreversible deterioration caused by the disease over time, giving rise to impairment that may reduce the patient's ability to achieve his or her full potential in life. While QOL has 3 dimensions (physical, social, and psychological), the CLCI concept incorporates additional aspects and integrates them into a comprehensive and holistic view of the patient. While QOL tests can generate similar data for different patients, CLCI is always individual and specific to each patient, as is each life journey. At the same time, we should also mention 2 of the principal limitations inherent in this concept: CLCI is difficult to quantify and the cumulative impairment is largely irreversible.

The components of CLCI include certain classic, well-known, and much studied factors for which empirical evidence exists, such as stigmatization and physical and psychological comorbidities. To these are added other aspects that have not yet been studied as much, including coping strategies, psychosocial support received, and the underlying personality traits of the patient, all of which can be moderating factors.

The chronic nature, visibility, and symptoms of psoriasis (for example, itching) have a considerable impact on the patient's life, which is even greater if the skin disease is accompanied by other physical comorbidities, such as psoriatic arthritis, Crohn disease, metabolic syndrome (myocardial infarction, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, obesity), or cardiovascular disease. Of these comorbidities, only obesity tends to manifest in adolescence or early adulthood, when it may generate physical and psychosocial problems that coincide with major life-changing decisions, and it can therefore exacerbate CLCI. The other comorbidities tend to appear later, but they significantly increase the disease burden on affected patients, further compromising their physical health and even increasing mortality.

Another important component of CLCI is the role of stigmatization: numerous studies and experience in clinical practice show that patients with a disease, such as psoriasis, that has visible symptoms may develop feelings of stigmatization and rejection.27–29 According to the definition of stigma, patients with psoriasis have visible lesions on their skin that lead them to be included in a social category whose members produce a negative response in others and are rejected by people not affected by such disease.

Feelings of stigmatization are confirmed in certain social situations when the lesions are visible to others (swimming pool, gym, beach). In such situations the patient may be closely observed or even asked to leave the premises or public facilities.2 In some patients, such experiences generate 2 types of behavior: first, the patient closely monitors the attitude of others and becomes hypersensitive to observation; second, these patients tend to anticipate rejection—that is, they avoid exposure to situations where they may be subject to the inspection of others. These reactions condemn the patient to a gradual and significant withdrawal from society.

The visibility of the lesions also has a negative effect on the patient's body image, and this, together with the feelings of stigmatization and experiences of social rejection, leads to low self-esteem, feelings of inferiority, a lack of confidence, and consequently decreased emotional wellbeing.2,30

This withdrawal from social activities compounded by the psychological and emotional symptoms (low self-esteem and poor self-image) inevitably reduces the patient's contact with the world, leading to a deterioration in personal and social relationships, lost job opportunities, and inhibitions in intimate and sexual relationships.3,4,30,31 The individual gradually starts to feel less worthwhile in terms of both self-esteem and their relationships with others; this in turn causes further withdrawal from society and further depletion of the ego.

Feelings of low self-esteem and personal and social withdrawal caused by stigmatization can precipitate the onset of psychological comorbidities, such as symptoms of anxiety and depression, in response to the situation the patient feels exposed to because of psoriasis. Feelings of anxiety or sadness may occur as isolated symptoms that interfere with the patient's performance and generate clinically significant distress, but they can also progress to full mental illness. In such cases, we encounter problems such as adaptive disorders, mood disorders (depressive or dysthymic disorder), anxiety disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia), and disorders caused by the consumption or abuse of alcohol or other intoxicants. Numerous authors have reported psychological symptoms—including anxiety, depression, social phobia and even suicidal ideation—in patients with psoriasis.32–35

Since they are a response to the chronic presence of psoriasis, anxiety and sadness persist over time, sometimes reaching pathological levels and producing behavioral changes.35 First, emotional disturbances may contribute to the exacerbation or worsening of psoriasis flares.35 Second, we know that the emotional disturbances cause behavioral changes, for example decreased adherence to treatment,36 and also increase the risk of inappropriate health-compromising addictive behaviors, including the consumption and abuse of alcohol.35–41 The prevalence of alcoholism is higher among patients with psoriasis than in the general population, and alcohol consumption increases the severity of the disease.37 There is evidence of a correlation between anxiety disorders and depression and a higher incidence of alcohol problems in patients with psoriasis.

Cumulative Life Course Impairment: Moderating FactorsThe concept of CLCI takes into account the stigmatization and physical and psychological comorbidities that affect many areas of these patients’ lives. For instance, psoriasis has been shown to have a significant influence on dating behavior and patients’ relationships with their partners because of the emotional problems it provokes (people who do not feel good about themselves are unlikely to feel good with someone else) and also due to the constraints imposed by the disease on family activities, a factor that might explain the higher divorce rate among these patients reported in some studies.67 Patients report that psoriasis gives rise to difficulties or has a negative impact on intimate sexual relationships, especially when there is genital involvement.45

Another area that can be affected is the patient's social and financial wellbeing; it has been observed that patients with psoriasis encounter difficulties in finding or keeping a job because of their low productivity and the loss of working time (days or hours) to accommodate treatments or because of flares. All these problems limit their chances of performing well in a job and therefore of securing and retaining properly paid employment.8–10,43 Low income can in turn lead to poor dietary habits (promoting obesity) and poor adherence to treatment due to financial problems, and these outcomes may further exacerbate or hinder the management of the disease.

Cross-sectional studies indicate that psoriasis is associated with feelings of stigmatization and with physical and emotional comorbidities, all of which eventually influence the social and economic development of these patients.8–10 The concept of CLCI allows the clinician to analyze how these factors—traditionally measured by way of cross-sectional surveys—produce long-term cumulative impairment that has a detrimental effect on the lives and development of the potential of all our patients. CLCI also helps us to evaluate the role of coping strategies and external determinants (e.g. family and social support) as factors that moderate this cumulative impairment.11,12

What Are the Factors That Can Moderate CLCI?Clearly, individuals will develop defense mechanisms to protect themselves against the aggression posed by psoriasis. Patients with ineffective coping strategies and those who have little or no social support will be more severely affected by any difficulty, stressful experience, or deterioration in their condition, however slight this may be. Patients who have a positive attitude and a good social support network, on the other hand, will tend to minimize the impact of any symptoms or problems caused by psoriasis, even when these are significant or their condition is in fact severe. This observation goes some way to explain why individuals with mild psoriasis may develop severe psychological symptoms, while others with more severe disease in terms of the extent of their lesions and the need for systemic treatment may not report the same high level of impact on their lives; the patient's experience depends on the effectiveness of their coping style and the positive role played by their social support network.42–46

Coping strategies—a key moderating factor in CLCI—are influenced by the patients’ coping styles (the way they adapt to and confront their illness) and their beliefs about psoriasis: the concept and symptoms of the disease (identity), its etiology (causes) and effects (consequences), the duration and stages of psoriasis and its treatment (timelines), and the degree of control they exercise over the disease and the flares (controllability). These coping strategies are in turn conditioned by each patient's personality.45

The importance of coping strategies and personality styles in psoriasis has been demonstrated by a number of studies. A study by Scharloo et al.44 showed that patients’ coping strategies and their perception of their condition account for the variability observed in clinical outcomes, with patients who have higher levels of perceived control and better emotional expression skills having better health outcomes over the course of a year than those who use passive and avoidant coping behaviors. In a follow-up study of patients treated for psoriasis, Kupfer et al.46 found that the symptom-free interval was longer in patients with a high sense of coherence (a personality style that helps the individual to deal with stressful situations and adapt to circumstances) than in those with a low sense of coherence.

Passive or negative coping strategies, such as fatalism, denial, hopelessness, helplessness, or the repression of emotions, have been associated with a greater presence of symptoms and emotional disorders. Some of these maladaptive strategies can initially relieve anxiety and distress, but in the long term they are counterproductive; for example, avoidance of social situations can reduce anticipatory anxiety in the short term, but over time this strategy will lead to patient isolation and progressive social withdrawal. Avoidance of the issue also has a negative impact on adherence to treatment, which in turn leads to a worsening of the skin disease, creating a vicious circle that further accentuates the patient's social isolation.

The importance of these factors is confirmed by the outcomes of cognitive-behavioral therapy in patients with psoriasis. The addition of such therapy to dermatologic treatment changes the patient's perception of their disease, provides appropriate coping strategies for each individual depending on their age and situation, and reduces psychological symptoms and consequently the clinical severity of psoriasis.47,48

In each case, the outcome is ultimately determined by the interaction of psychological factors, physical comorbidities, and feelings of stigmatization moderated by the patient's coping strategies and personality style. Obviously, these factors are not stable and will vary depending on the time of life of the patient, and it is this variation that will determine the patient's greater or lesser risk of vulnerability to cumulative impairment due to psoriasis. In other words, a patient may function well during a particular period even with severe psoriasis if they have strong social support, good coping strategies, and they do not experience social stigmatization. On the other hand, a patient with mild psoriasis may experience situations of stigmatization, experience intense anxiety, and lack adequate family and social support; in such cases the patient is at high risk for CLCI.12

1Advantages, Applications, and Limitations of CLCIFull implementation of the CLCI concept allows the clinician to go beyond the fixed, one-off, and incomplete picture provided by quality-of-life questionnaires to analyze how factors such as stigma or physical and psychological comorbidities, traditionally measured using a cross-sectional methodology, gradually produce cumulative impairment over time in all these patients, hindering the development of their full life potential and influencing the major decisions that will shape their future lives. It can also help us to determine the role played by the factors that moderate this cumulative impairment, such as coping strategies (adaptive or maladaptive) and external factors, for example family and social support. As an analogy, CLCI allows us to read each individual's personal and psychosocial “black box”, which is strongly influence by their disease. Thus, it could allow us to ascertain to what extent psoriasis has contributed to shaping the person the patient has become. If we had access to the unique chain of psychosocial events determined by psoriasis that have affected the life of a particular individual, it seems likely that we could establish the importance of a proactive approach from the point of view of both medical treatment and psychological interventions—individual or group therapy—that would help the patient to cope more successfully with their condition.

At this point, we can clearly see the major limitation of CLCI. Even when we fully understand the concept and its implications for the life of each patient and the treatment of their condition, the fundamental question remains. How can we evaluate CLCI? What parameters should we use? At present there is no validated instrument for quantifying or assessing CLCI, although some proposals have been made. Warren et al.12 undertook a series of interviews to qualitatively identify patients’ CLCI by analyzing each individual's history of the course of their psoriasis and its impact on their lives. They observed that, although all the factors identified using the theoretical model exist to varying degrees in all these patients, the interaction of the components creates an individual profile of accumulated impairment in each case.

Awareness among dermatologists of the concept of CLCI and its implications would not only help them to identify and understand their patients vulnerability to such impairment and allow them to address risk factors at an early stage, but would also make it possible to tailor treatment to the individual and to foster improved treatment adherence. Improved adherence to treatment and a stronger link between dermatologist and patient would help the patient to develop adaptive coping strategies and reduce common negative behaviors, such as alcohol consumption or avoidance of social situations. It would also ensure that patients would receive prompt psychological care when they needed help to deal with their psychological symptoms, and would therefore improve the general wellbeing of patients with psoriasis.

Ethical ResponsibilitiesProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their hospitals concerning the publication of patient data and that all patients included in this study were appropriately informed and gave their written informed consent.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no private patient data are disclosed in this article.

FundingThe authors have received no remuneration for writing this article. No person other than the authors participated in the writing or review of the text.

Conflicts of InterestSandra Ros and José Manuel Carrascosa have participated as consultants in the discussion that gave rise to the concept of CLCI as members of the CLCI Steering Committee, sponsored by Abbott Laboratories.

Please cite this article as: Ros S, Puig L, Carrascosa JM. Discapacidad acumulada en el transcurso vital: la cicatriz de la psoriasis en la vida del paciente. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:128–134.