Demodex folliculorum (DF) mites are inhabitants of the human pilosebaceous unit that have a predilection for the face due to high sebum concentration in this area. When cutaneous diseases are clinically characterized by a large number of DF mites we talk about demodicosis, which may be found more frequently in immunocompromised patients.1 We present a case series of 4 patients with hematological diseases that developed demodicosis after receiving a bone marrow transplant (BMT).

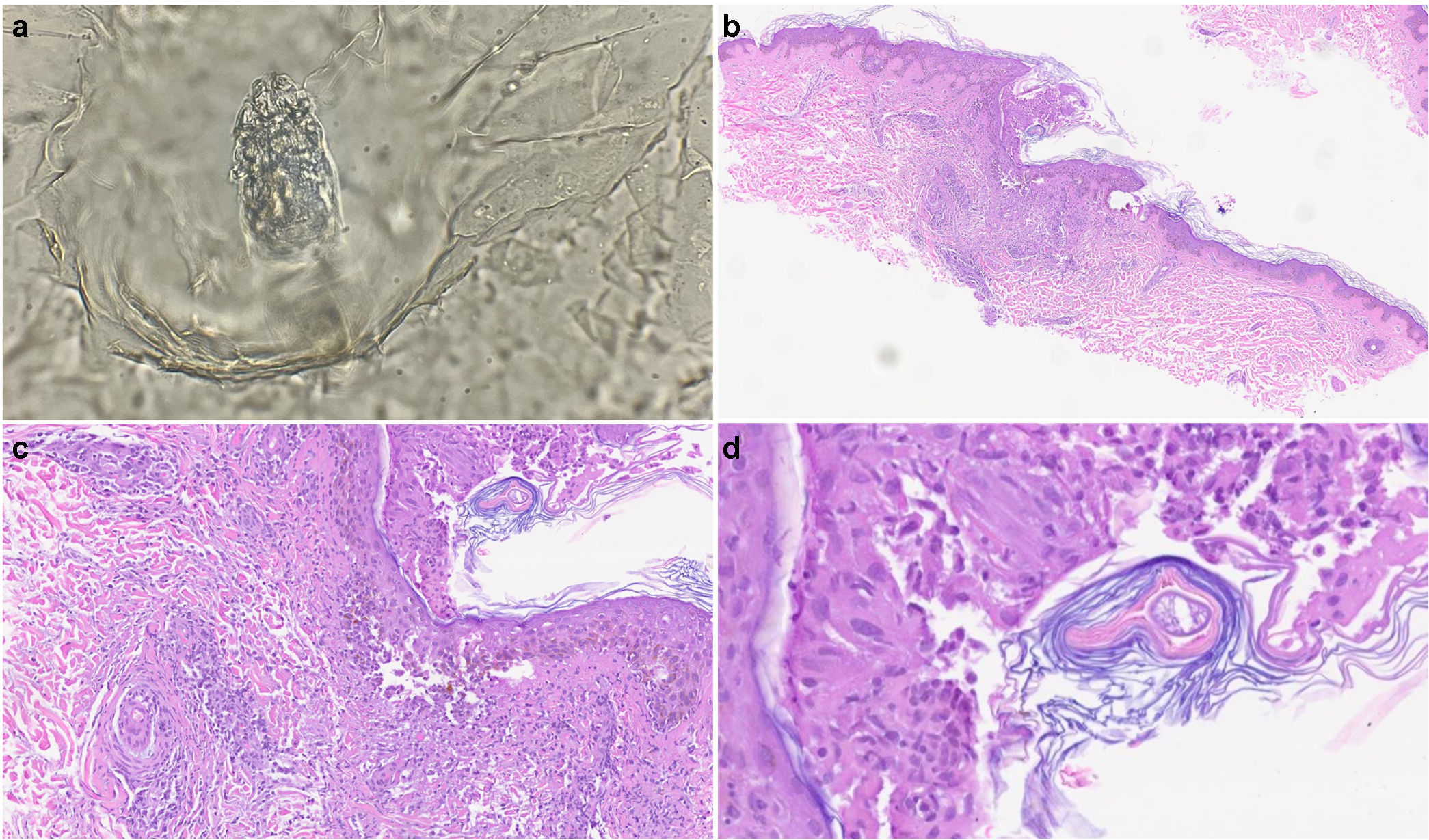

Four patients from our hospital with leukemia developed a pruritic and acneiform rash after BMT and chemotherapy between 2021 and 2022. Table 1 illustrates their clinical information. All patients had a similar presentation (were under 30 and had a previous diagnosis of leukemia which required BMT and chemotherapy. None of them had any past medical history of acne, demodicosis, or rosacea. In all cases a pruritic micropustular rash was suddenly found on the face which progressed toward the neck and chest 7–19 days after BMT (Fig. 1). No associated systemic symptoms were reported. Dermoscopy of the pustular skin lesions revealed the presence of spikes, and a parasitological skin test performed by direct microscopic examination revealed the presence of a high DF density in all patients (Fig. 2a). Bacterial cultures and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) skin test for human herpes simplex 1 and 2 and varicella zoster virus tested negative in all 4 patients. In patient #3, demodicosis was also confirmed by histopathological examination, which revealed the presence of an inflammatory infiltrate around the hair follicles and the presence of an inflammatory lesion formed by giant cells and granulomas surrounding an infundibulum (Fig. 2b–d). Patients were received topical ivermectin showing complete remission of the lesions 2 weeks into treatment. No new flares of skin lesions have been detected at the 6-month follow-up.

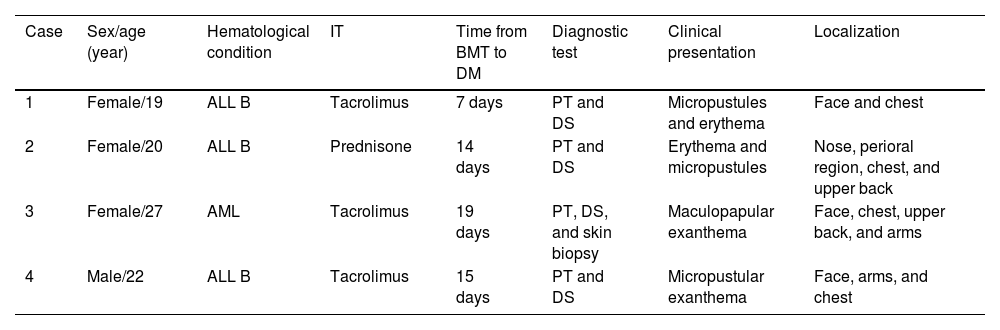

Clinical characteristics of patients with demodicosis after receiving a bone marrow transplant (BMT).

| Case | Sex/age (year) | Hematological condition | IT | Time from BMT to DM | Diagnostic test | Clinical presentation | Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female/19 | ALL B | Tacrolimus | 7 days | PT and DS | Micropustules and erythema | Face and chest |

| 2 | Female/20 | ALL B | Prednisone | 14 days | PT and DS | Erythema and micropustules | Nose, perioral region, chest, and upper back |

| 3 | Female/27 | AML | Tacrolimus | 19 days | PT, DS, and skin biopsy | Maculopapular exanthema | Face, chest, upper back, and arms |

| 4 | Male/22 | ALL B | Tacrolimus | 15 days | PT and DS | Micropustular exanthema | Face, arms, and chest |

Abbreviations: ALL: acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML: acute myeloblastic leukemia; BMT: bone marrow transplant; IT: immunosuppression therapy; DM: demodicosis; DS: dermoscopy; PT: parasitological test.

Clinical presentation of demodicosis in patients #1 (a), #2 (b), #3 (c–e) and #4 (f). (a) Small pustular lesions over the forehead. (b) Maculopapular rash and pustules on the upper back. (c) Confluent maculopapular exanthema involving the perioral and malar regions. (d, e) Maculopapular rash and micropustules over chest and back. (f) Malar pustules and erythema.

Parasitological test and histopathological images of skin lesions. (a) Parasitological skin test showing DF. (b, c) At lower power, dermatopathology images show a pronounced perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate around hair follicles (hematoxylin-eosin staining, original magnification (b) ×40 and (c) ×100. (d) High power image showing a tubular structure consistent with DF (hematoxylin–eosin staining, original magnification ×400).

DF is a saprophytic mite of the human pilosebaceous unit, first described in 1841 by Henle and Berger. It is commonly found on the face, especially the forehead, cheeks, eyelids, nasolabial folds, and nose due to the high density of sebaceous glands found in these areas. Rates of colonization in the general population usually range from 20% up to 80%. DF may be also found in the ear canals and other areas of the body and has been involved in many dermatological disorders, such as rosacea, pustular folliculitis, or follicular pityriasis.2

The presence of follicular spines caused by the protrusion of mites and keratin from the follicle is referred to as pityriasis folliculorum. When demodicosis occurs and large quantities of mites are present in the epithelium of the skin, pruriginous follicular papules and visible inflammatory lesions may occur. Clinical presentation can vary from scales and erythema over the forehead and nose to a symmetrical papulopustular eruption of malar distribution over existing diseased skin.3

Demodex proliferation can be impacted by multiple factors, such as hypothyroidism, pregnancy, diabetes, immunosuppressive therapies, Staphylococcus epidermidis infection, and genetic background. In immunocompromised patients, a pruritic exanthema on extended areas such as the trunk and upper extremities can be found. Moreover, the presence of pustules and a lack of improvement after topical corticosteroids should also be indicative of the presence of DF. A few cases of demodicosis in patients with lymphoma or leukemia have been reported in the literature, especially when patients are recovering from an allogenic bone marrow transplant.4 Accurate diagnosis in these patients is critical as the clinical presentation of the disorder can be similar to acute graft-versus-host disease of the skin.

For diagnosis, the presence of Demodex mites can be confirmed through examination using light microscopy of skin scrapes or confocal laser scanning in vivo microscopy. Moreover, a skin biopsy can be indicative of the presence of demodicosis when follicular spongiosis and a perifollicular lymphoid infiltrate are found as was observed in our patients.

Many treatment options, such as permethrin, oral ivermectin or metronidazole have demonstrated the efficacy profile of Demodex infestation. However, topical ivermectin seems to be beneficial in immunosuppressed patients with extended and symptomatic skin eruptions.5

Our patients developed a perioral eruption which extended to the rest of the face, arms, back and pre-sternal region. In addition to parasitological examination by pustular lesions scrapping, skin biopsy and detection of DF by direct microscopy allowed us to establish the correct diagnosis. Moreover, complete remission of the skin eruption was seen after topical ivermectin, which reaffirmed our diagnosis. No side effects were reported after treatment in these patients.

In conclusion, physicians should remember that demodicosis should be taken into consideration when acute pustular and pruritic skin eruptions involving face and upper regions of the body appear after a bone marrow transplant. Of note, the transition from the asymptomatic colonization of DF to clinical demodicosis is a more common finding in immunosuppressed patients.3 Therefore, an easy and useful technique as parasitological examination should be included in the study protocol of pustular lesions in this group of patients.

Conflict of interestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.