Catamenial dermatitis is a rare disease that presents clinically as monthly flares of variable lesions on the skin caused by the hormonal fluctuations of the menstrual cycle.

A 46-year-old woman presented with monthly flares of a lesion on her right forearm that first appeared in 2013. An intrauterine device (Mirena, Bayer Hispania SL) inserted in 2011 had been removed some months earlier. She was a smoker and occasionally took ibuprofen, although never for dysmenorrhea. The patient reported that the lesion appeared 3-4 days before menstruation, with spontaneous resolution on days 4-5 of her menstrual cycle.

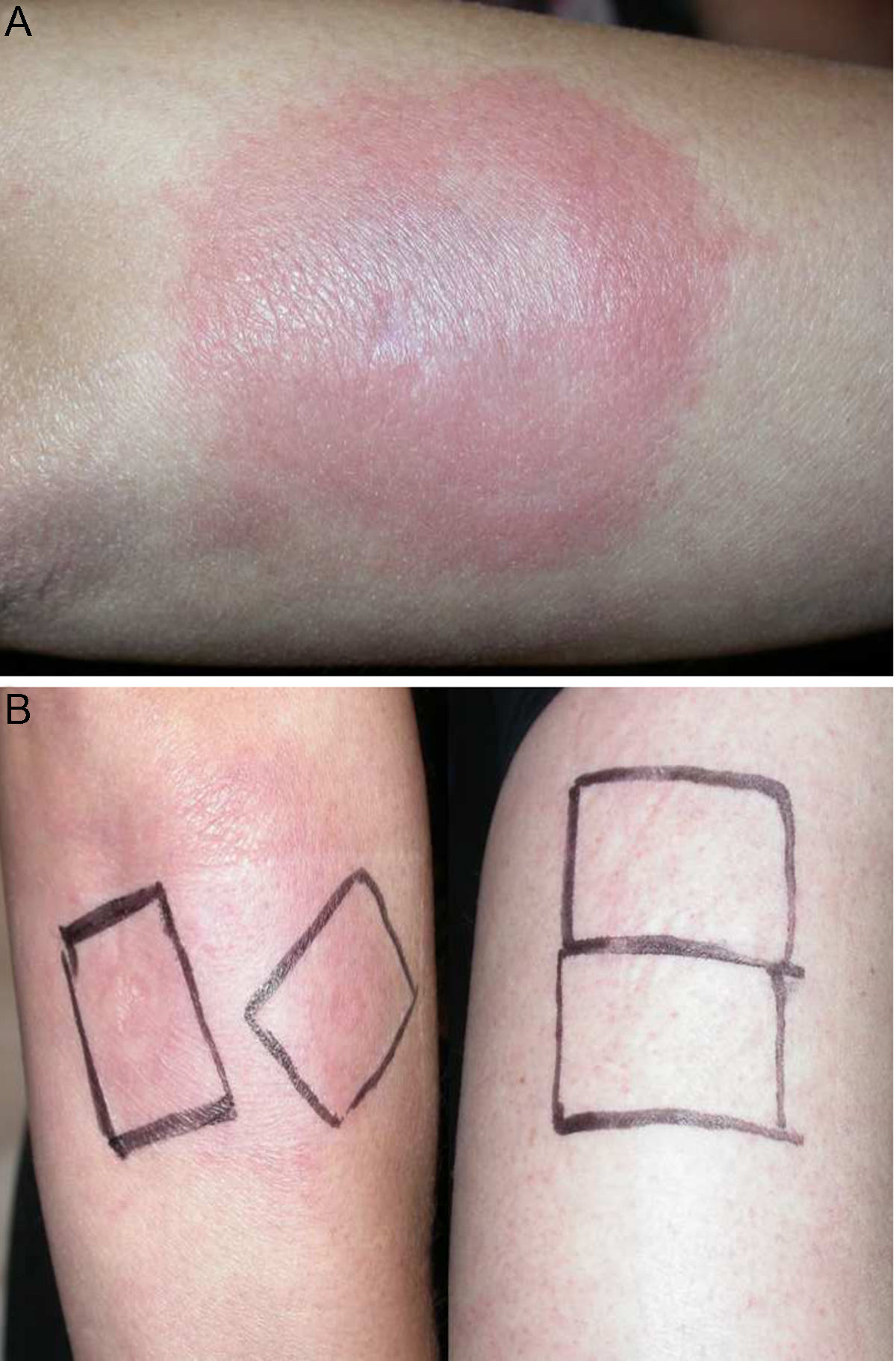

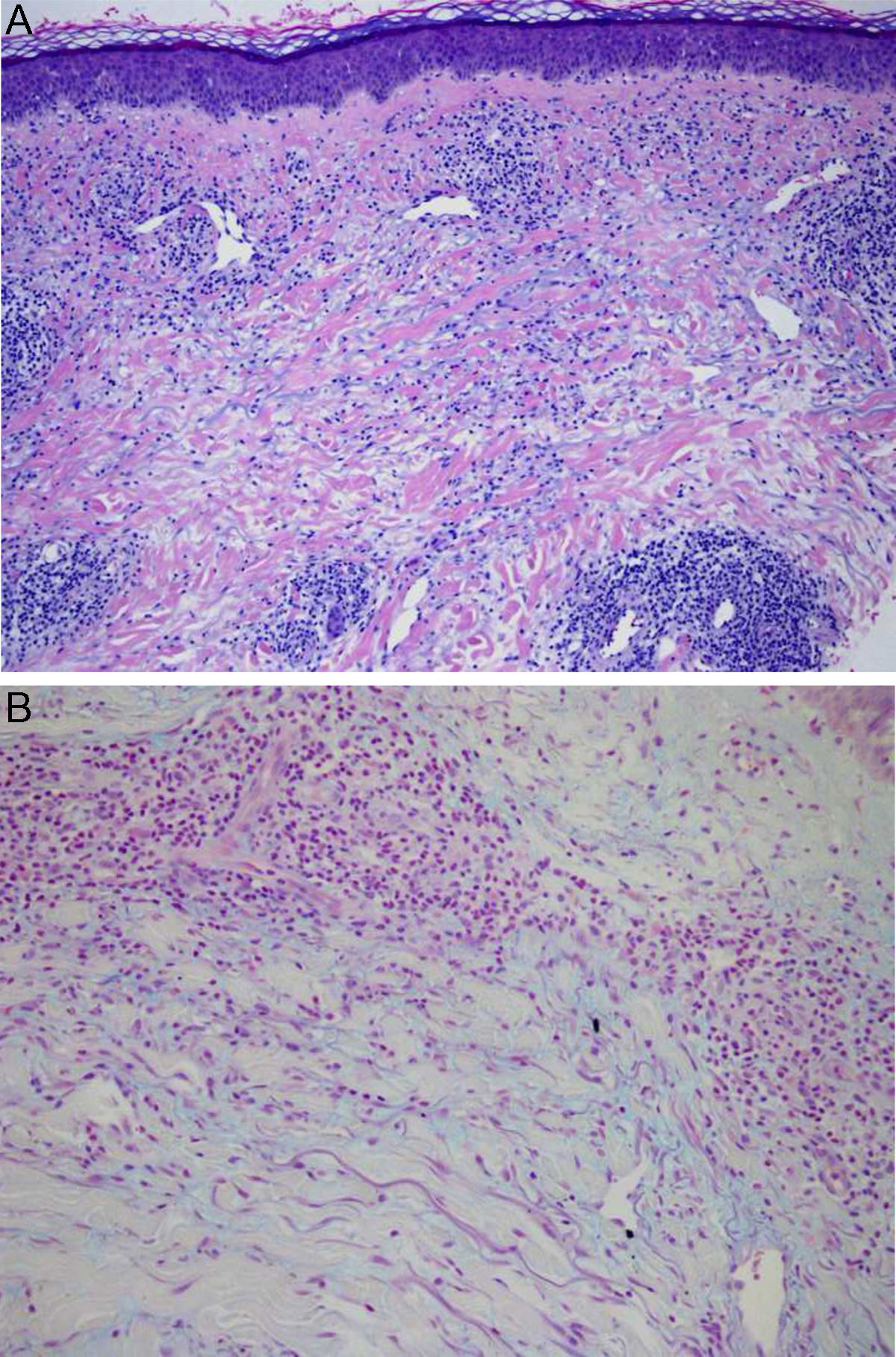

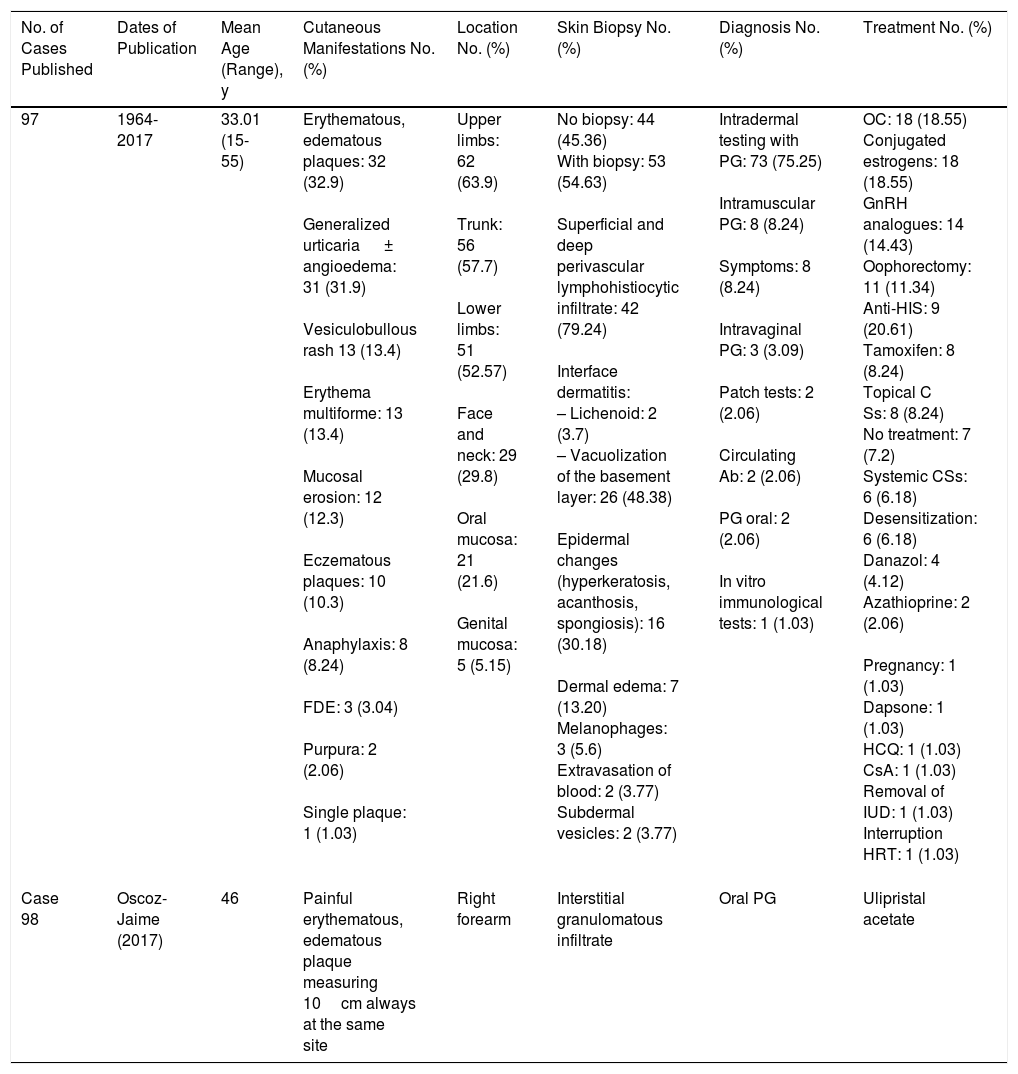

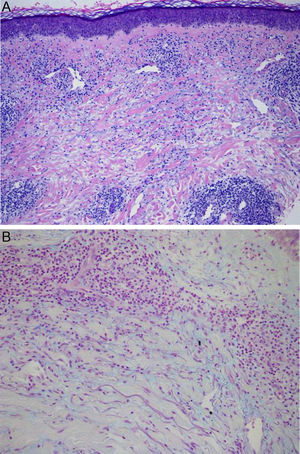

Physical examination revealed the presence of a tender erythematous, edematous plaque measuring some 10cm in diameter on the right forearm (Fig. 1). Patch testing was performed with the standard series of the Spanish Contact Dermatitis and Skin Allergy Research Group (Grupo Español en Investigación de Dermatitis de Contacto y Alergia Cutánea [GEIDAC]), with progesterone, and with NorLevo (Laboratoire HRA-Pharma) in petrolatum, and Progeffik (Laboratorios Effik) applied directly on the area of the lesion and on healthy skin (Fig. 1B). The results were negative both at 48hours and at 96hours, as was intradermal skin testing, which was performed with progesterone (Carborprot, Pfizer) and read 15minutes and 96hours after infiltration. Biopsy confirmed the presence of a dense interstitial lymphohistiocytic infiltrate and mucin between collagen bands in the dermis (Fig. 2 A and B).

A, Erythematous, edematous plaque on the right forearm that is tender and infiltrated to touch measuring some 10cm in diameter. Patch test with progesterone, which was negative at 96hours, and with NorLevo in petrolatum and Progeffik applied directly on the area of the lesion and on healthy skin (B).

Both before and during the outbreak, the patient received nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and topical and oral corticosteroids, with partial resolution of symptoms but no prevention of flare-ups during the following months. She subsequently started treatment with Progeffik 300mg/d for 1 month. The lesion remained unchanged during this period, thus leading to a diagnosis of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis. At this point, the patient began treatment off-label with ulipristal acetate (Esmya, Gedeon Richter Iberica) 5mg/d over periods of 3 months with rest periods every 1-2 months. The skin lesions resolved completely during treatment. She has been receiving treatment with ulipristal acetate for 9 months. After the 12th month of treatment, the drug will be stopped, and a wait-and-see approach will be adopted until the patient reaches the menopause.

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is a catamenial dermatosis characterized by the appearance of premenstrual skin lesions owing to increased progesterone levels during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle.1

The etiology and pathogenesis of the disease remain unknown, probably because of the low number of cases reported to date (Table 1). Nevertheless, antiprogesterone antibodies are thought to be produced as a result of sensitization to progesterone. The antibodies trigger clinical manifestations, since ovulation induces an increase in progesterone during the luteal phase.1,2 A history of exposure to systemic contraceptives has been reported in up to 66% of cases.1 Thus, it is thought that exposure could lead to sensitization to exogenous hormones and triggering of symptoms as the result of a cross-reaction with endogenous progesterone.1 In the remaining 33% of cases, there was no previous exposure to exogenous hormones, and other pathologic autoimmune mechanisms against endogenous progesterone (eg, pregnancy and menarche)1–4 are thought to be responsible.

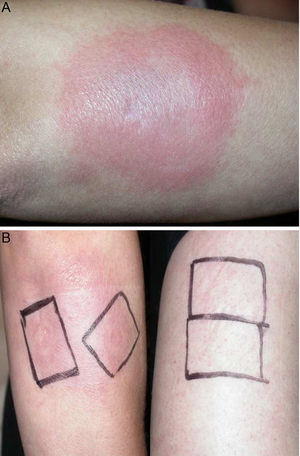

Summary of Published Cases.

| No. of Cases Published | Dates of Publication | Mean Age (Range), y | Cutaneous Manifestations No. (%) | Location No. (%) | Skin Biopsy No. (%) | Diagnosis No. (%) | Treatment No. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 97 | 1964-2017 | 33.01 (15-55) | Erythematous, edematous plaques: 32 (32.9) Generalized urticaria ± angioedema: 31 (31.9) Vesiculobullous rash 13 (13.4) Erythema multiforme: 13 (13.4) Mucosal erosion: 12 (12.3) Eczematous plaques: 10 (10.3) Anaphylaxis: 8 (8.24) FDE: 3 (3.04) Purpura: 2 (2.06) Single plaque: 1 (1.03) | Upper limbs: 62 (63.9) Trunk: 56 (57.7) Lower limbs: 51 (52.57) Face and neck: 29 (29.8) Oral mucosa: 21 (21.6) Genital mucosa: 5 (5.15) | No biopsy: 44 (45.36) With biopsy: 53 (54.63) Superficial and deep perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate: 42 (79.24) Interface dermatitis: – Lichenoid: 2 (3.7) – Vacuolization of the basement layer: 26 (48.38) Epidermal changes (hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, spongiosis): 16 (30.18) Dermal edema: 7 (13.20) Melanophages: 3 (5.6) Extravasation of blood: 2 (3.77) Subdermal vesicles: 2 (3.77) | Intradermal testing with PG: 73 (75.25) Intramuscular PG: 8 (8.24) Symptoms: 8 (8.24) Intravaginal PG: 3 (3.09) Patch tests: 2 (2.06) Circulating Ab: 2 (2.06) PG oral: 2 (2.06) In vitro immunological tests: 1 (1.03) | OC: 18 (18.55) Conjugated estrogens: 18 (18.55) GnRH analogues: 14 (14.43) Oophorectomy: 11 (11.34) Anti-HIS: 9 (20.61) Tamoxifen: 8 (8.24) Topical C Ss: 8 (8.24) No treatment: 7 (7.2) Systemic CSs: 6 (6.18) Desensitization: 6 (6.18) Danazol: 4 (4.12) Azathioprine: 2 (2.06) Pregnancy: 1 (1.03) Dapsone: 1 (1.03) HCQ: 1 (1.03) CsA: 1 (1.03) Removal of IUD: 1 (1.03) Interruption HRT: 1 (1.03) |

| Case 98 | Oscoz-Jaime (2017) | 46 | Painful erythematous, edematous plaque measuring 10cm always at the same site | Right forearm | Interstitial granulomatous infiltrate | Oral PG | Ulipristal acetate |

Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; anti-HIS, antihistamines; CS, corticosteroids; CsA, ciclosporin A; FDE, fixed drug eruption; GnRH, gonadotropin-releasing hormone; HCQ, hydroxychloroquine; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; IUD, intrauterine device; OC, oral contraceptive; PG: progesterone.

The clinical presentation of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is indeed very diverse. There have been reports of cases compatible with Steven-Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, dermatitis herpetiformis, eczema, urticaria, stomatitis, petechiae,3 or, rarely, fixed drug eruption,3,5,6 as in the present case. Symptoms usually appear 3-10 days before menstruation and resolve 5-10 days after the onset of menstruation, coinciding with the fall in progesterone levels.2,7

No criteria have been established for confirming a diagnosis of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis,1,8 although most authors propose 3criteria:

Cyclical symptoms: onset some days before menstruation (3-10 days) and spontaneous resolution after menstruation.

Interruption of flare-ups with treatments that inhibit ovulation or increases in progesterone levels.

Triggering of symptoms by tests of sensitization to progesterone (contact allergy tests,9 intradermal tests,1,3,9 oral challenge tests,1,9 intramuscular tests,1,3 and vaginal tests with progesterone3) or confirmation of circulating antiprogesterone antibodies.1

The objective of treatment is to inhibit ovulation in order to block the mechanisms that cause high levels of progesterone during the second phase of the cycle. Today, oral contraceptives are the first-line treatment option. In any case, depending on the age and clinical characteristics of the patient, other drugs can also be used (eg, conjugated estrogens, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs, tamoxifen, and danazol). Bilateral oophorectomy can be performed in severe and refractory cases.2 Ulipristal acetate is a progesterone receptor antagonist that acts on progesterone levels. It is thought to inhibit ovulation by blocking both expression of progesterone-dependent genes and peaks of luteinizing hormone.10 Given the patient's age and the fact that she was a smoker, we opted for treatment with ulipristal acetate as a valid alternative.

Autoimmune progesterone dermatitis is an extremely rare skin disease if we take into account the number of women who are treated with oral contraceptives throughout the world. This observation is relevant, since the incidence of the condition is expected to increase in women as a consequence of increased use of oral contraceptives. The present case is the third to date published by Spanish authors4,7 and the first case of autoimmune progesterone dermatitis treated effectively with ulipristal acetate. We propose ulipristal acetate as an effective therapeutic option in selected cases.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

NoteAs of February 9, 2018 (after treatment was started in the present case), the Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices) published the following alarm: “After the notification of severe cases of liver injury in women treated with Esmya, provisional measures have been taken while a detailed analysis of all the available information is being completed. Therefore, as precautionary measures, liver function should be monitored, and no new treatment should be started”.

Please cite this article as: Oscoz-Jaime S, Larrea-García M, Mitxelena-Eceiza MJ, Abián-Franco N. Respuesta de la dermatitis autoinmune por progesterona al acetato de ulipristal. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019;110:78–81.