We report the case of a 68-year-old man diagnosed with a nodular melanoma (Breslow depth, 11mm) in the right submammary region. He had no relevant past history and reported taking no medication, Radiography showed enlarged bilateral axillary, mediastinal, and hilar lymph nodes and multiple bilateral micronodules in the upper and lower lobes of the lung. These nodules showed high uptake, suggestive of metastatic lesions, on the positron emission tomography–computed tomography scan. Assessment of the BRAF V600E mutation was positive. With a diagnosis of BRAF-positive stage IV metastatic melanoma, treatment was initiated with vemurafenib 960 mg every 12hours. No reduction was observed in the metastases after almost a month of treatment.

At week 4 of treatment, the patient presented at the emergency department of his reference hospital with itching and reddening of the face and scalp. He reported no previous symptoms or fever. The physical examination revealed an exanthematous macular-papular rash on the neck, trunk, and extremities. The patient was admitted and treated with oral corticosteroids and antibiotics. Over the next 48hours, he developed dysphagia, a tendency towards low blood pressure, and decreased urine output. A severe drug reaction was suspected and the patient was transferred to the burn unit at our hospital. On arrival, 72hours after the onset of symptoms, he was afebrile, hemodynamically stable, and breathing spontaneously. Physical examination showed extensive body surface involvement (85%) and epidermal detachment (60%), in addition to erosions affecting the ocular, oral, and genital mucosa (Figs. 1 and 2). His heart rate was 95bpm and oxygen saturation was 100%.

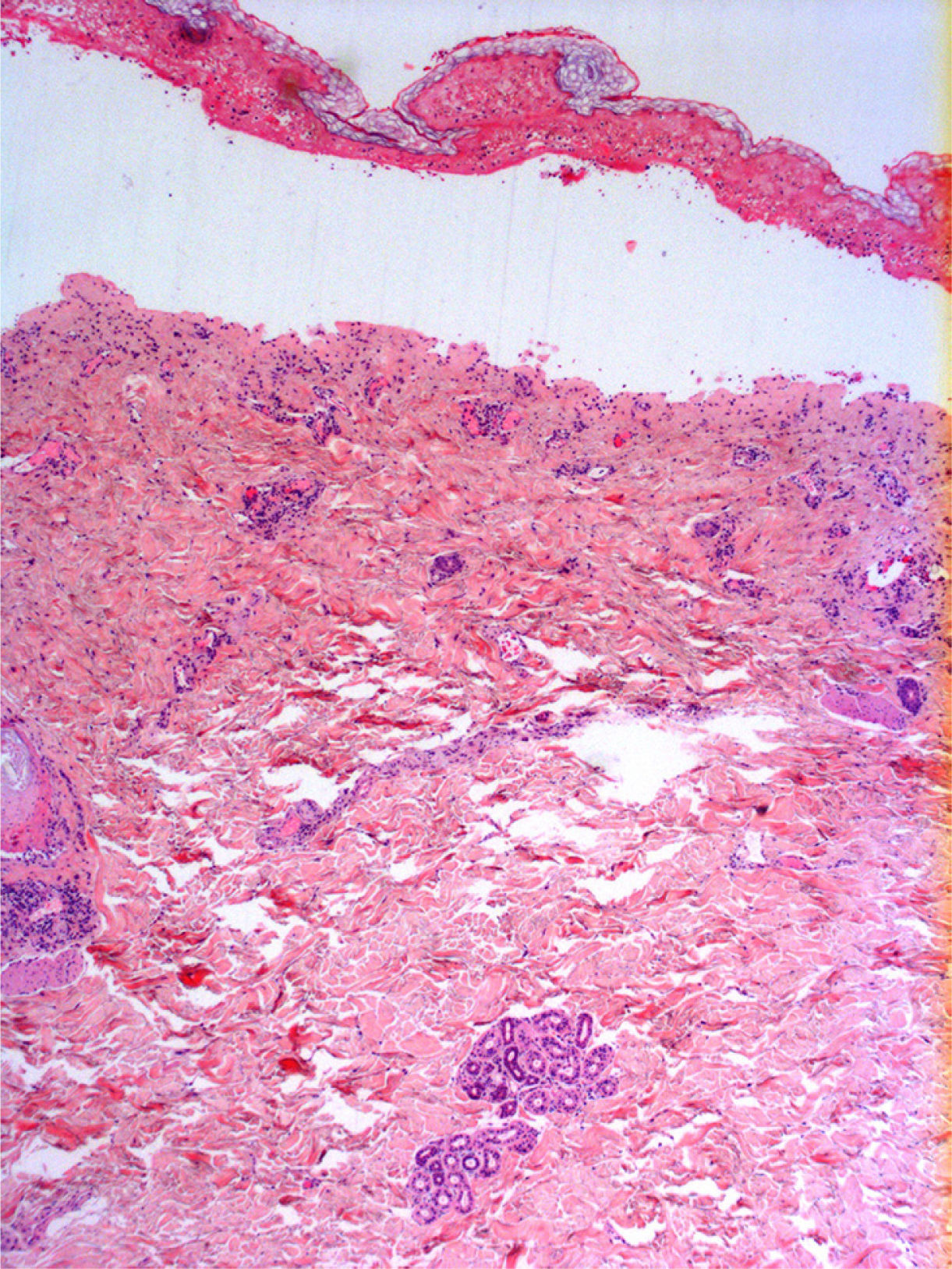

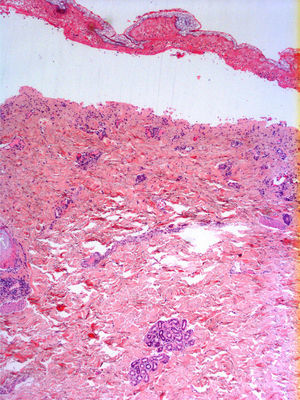

Radiologic evaluation on admission showed enlarged hila and hilar and parahilar lymph nodes. There were no areas of consolidation. The most relevant laboratory findings were a C-reactive protein level of 86, a prothrombin ratio of 60.5%, and an internationalized normal ratio of 1.25. Biopsy showed extensive confluent necrosis in the epidermis and subepidermal detachment. There was a predominantly perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate in the dermis (Fig. 3). The patient was diagnosed with toxic epidermal necrolysis due to vemurafenib, with a score of 3 on the SCORTEN scale. Vemurafenib had been withdrawn on admission, and treatment initiated with intravenous ciclosporin 75mg every 12hours, in addition to selective digestive decontamination, vitamin and nutritional support, and fluid therapy. The necrotic areas of the skin were removed, cleaned with saline solution and chlorhexidine, and covered with Biobrane dressings (Smith & Nephew).

During the first 48hours of admission at our hospital, the lesions progressed to affect 90% of the total body surface. On day 4, the necrolysis stopped and the first signs of reepithelialization were seen. Reepithelialization was complete 2 weeks later.

Immediate complications were femoral deep vein thrombosis, followed by pulmonary embolism. Delayed complications included nail loss and adhesions in both external ear canals and in the balanopreputial sulcus. Finally, the patient required amniotic membrane transplantation due to necrosis of the conjunctival membranes.

The patient was discharged a month later. Ciclosporin was progressively tapered to zero, with administration of 150mg and 100mg for 5 days each. The patient returned to his reference hospital, where treatment with ipilimumab and radiation therapy reduced the metastases. He is currently stable and in good general health.

Vemurafenib is a selective inhibitor of the BRAF V600 mutation that was approved by the US Food and Drug Agency for the treatment of metastatic or unresectable melanoma in 2011.1 About 40% to 60% of melanomas are BRAF-positive, and the mutation causes constitutive activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway, which in turn leads to uncontrolled cell growth and increased cell proliferation and invasive capacity.2,3

Most mutations are V600E (valine to glutamic acid substitution), but there are also other less common mutations, such as V600K.4

In the BRIM3 phase 3 clinical trial, 675 patients were randomly allocated to treatment with either vemurafenib or dacarbazine. In the vemurafenib group, there was a 63% reduction in the risk of death and a 74% reduction in the risk of death or disease progression.1 In addition, the phase 1 and 2 trials showed response rates of up to 50% and an overall mean survival of between 14 and 16 months.5,6

Treatment with vemurafenib, however, is not free of adverse effects, among which cutaneous toxicity is the most common. The most common cutaneous effects are rash, photosensitivity, pruritus, alopecia, palmar erythrodysesthesia, verrucal keratosis, keratoacanthomas, and squamous cell carcinomas. Almost 40% of patients develop a rash, which generally does not require treatment to be discontinued as most cases are mild (grade 1) or moderate (grade 2). Dose reductions or treatment discontinuation are only necessary in patients with severe rash (grade 3) or intolerable grade 2 rash.7

Severe cutaneous reactions to vemurafenib are very uncommon, and just 1 case of Steven-Johnson syndrome and another of toxic epidermal necrolysis were reported in the BRIM3 study.1

However, new cases of severe cutaneous toxicity have appeared since the launch of the drug. Wantz et al.8 reported one of the first cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis due to vemurafenib in Europe. Treatment was discontinued and the necrolysis resolved, but the patient died from melanoma some months later.8

The suspected drug should be withdrawn in all cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis and patients should be managed by specialized units. Although is no scientific evidence supporting the use of systemic therapy, at our hospital we use ciclosporin, as it rapidly stops progression of the rash, is well tolerated, and does not increase the risk of infection or death.9

We have presented the first case of toxic epidermal necrolysis due to vemurafenib in Spain. We believe that patients on this drug should be closely monitored by a dermatologist, with careful attention paid to the development of skin rash with signs of severity, such as epidermal detachment or mucosal involvement.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Lapresta A, Dotor A, González-Herrada C. Necrólisis epidérmica tóxica por vemurafenib. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:682–683.