Patients with severe psoriasis have an increased cardiovascular (CV) risk and prevalence of subclinical coronary artery disease (CAD). Coronary artery calcium (CAC) testing can detect subclinical CAD and improve cardiovascular risk assessment beyond clinical scores.

ObjectivesEvaluate the presence and magnitude of subclinical CAD determined by CAC score among the different ESC/EAS CV risk categories, as well as the potential for risk reclassification, in patients with severe psoriasis from a low CV risk population.

MethodsUnicentric cross-sectional study in 111 patients with severe chronic plaque psoriasis from a low CV risk population in the Mediterranean region. Patients were classified into four CV risk categories according to the ESC/EAS guideline recommendations and HeartScore/SCORE calibrated charts. Patients underwent coronary computed tomography to determine their CAC scores. Patients in the moderate-risk category with a CAC score of ≥100 were considered to be reclassified as recommended by the 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines. Reclassification was also considered for patients in the low-risk category with a CAC score>0.

ResultsPresence of subclinical CAD was detected in 46 (41.4%) patients. These accounted for 86.2% of patients in high/very-high-risk categories and 25.6% of patients in non-high-risk categories. Fourteen (17.1%) of the patients in non-high-risk categories were reclassifiable due to their CAC score. This percentage was higher (25%) when considering the moderate-risk category alone and lower (13.8%) in the low-risk category. Age was the only variable associated with presence of subclinical CAD and reclassification.

ConclusionsOver 40% of patients with severe psoriasis from a low-risk region and up to 25% of those in non-high-risk categories have subclinical CAD. CAC appears to be useful for reclassification purposes in CV risk assessment of patients with severe psoriasis. Further research is required to elucidate how CAC could be implemented in everyday practice at outpatient dermatology clinics dedicated to severe psoriasis.

Los pacientes con psoriasis severa tienen riesgo cardiovascular (CV) incrementado, así como prevalencia de la enfermedad de las arterias coronarias (EAC) subclínica. El examen de calcio en las arterias coronarias (CAC) puede detectar la EAC subclínica y mejorar la evaluación del riesgo CV más allá de las puntuaciones clínicas.

ObjetivosEvaluar la presencia y magnitud de la EAC subclínica determinadas mediante la puntuación CAC entre las diferentes categorías de riesgo CV de ESC/EAS, así como el potencial de reclasificación del riesgo, en pacientes con psoriasis severa, procedentes de una población de riesgo CV bajo.

MétodosEstudio transversal unicéntrico de 111 pacientes con psoriasis crónica en placa procedentes de una población de bajo riesgo CV de la región mediterránea. Los pacientes fueron clasificados en cuatro categorías de riesgo CV conforme a las recomendaciones de la guía ESC/EAS y la tabla de calibración HeartScore/SCORE. Se realizó a los pacientes una tomografía computarizada para determinar sus puntuaciones CAC. Se consideró que los pacientes de la categoría de riesgo moderado con una puntuación CAC≥100 debían ser reclasificados, conforme a las guías ESC/EAS de 2019. También se reconsideró la reclasificación para aquellos pacientes de la categoría de riesgo bajo con una puntuación CAC>0.

ResultadosLa presencia de EAC subclínica fue detectada en 46 pacientes (41,4%), que representaron el 86,2% de los pacientes incluidos en las categorías de riesgo alto/muy alto, y el 25,6% de los pacientes de las categorías de riesgo no alto. Catorce pacientes (17,1%) de las categorías de riesgo no alto no fueron reclasificables debido a su puntuación CAC. Este porcentaje fue más alto (25%) al considerar la categoría de riesgo moderado en solitario, y más bajo (13,8%) en la categoría de riesgo bajo. La edad fue la única variable asociada a la presencia de EAC subclínica y reclasificación.

ConclusionesMás del 40% de los pacientes con psoriasis severa procedentes de una región de bajo riesgo, incluyéndose un 25% de los mismos en las categorías de riesgo no alto, tenían EAC subclínica. CAC parece ser de utilidad a efectos de reclasificación a la hora de evaluar el riesgo CV de los pacientes con psoriasis severa. Es necesaria más investigación para esclarecer el modo de implementar CAC en la práctica diaria en las clínicas ambulatorias de dermatología dedicadas a la psoriasis severa.

Plaque psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease with a prevalence of approximately 2% among the general population.1 It has been estimated that approximately 20% of patients present with severe forms of the disease.2 Patients with severe psoriasis have been found to be at a higher attributable risk of major cardiovascular (CV) events.3,4 This increased CV risk seems to be independent of and underestimated by traditional clinical risk factors.5,6 Several studies have also found an increased burden of subclinical atherosclerosis observed by different imaging techniques, including coronary artery calcium (CAC) detection by computed tomography.7,8

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death worldwide and CV risk prevention remains of great importance.9 Preventive strategies are largely guided by classification in CV risk categories determined by tools based on traditional risk factors, with the HeartScore/Systemic Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE) being extensively used in Europe.9,10 Non-invasive imaging techniques that detect subclinical atherosclerosis have been shown to be predictive of CV events, and are considered useful complementary tools in CV risk assessment among certain subgroups of individuals. These techniques include carotid and femoral ultrasonography, CAC testing, coronary CT angiography and vascular Positon Emission Tomography. Detection of CAC with computed tomography has been shown to adequately estimate atherosclerotic burden and strongly associate with CV events.9,11 Prospective studies have found CAC score to have the best reclassification ability among these techniques when added to traditional risk factors.12–14 These findings together with the technique's inherent advantages have resulted in several guides and consensus recommending its use in primary prevention for asymptomatic individuals at intermediate CV risk.9,15–17 Its use has also been proposed for special populations such as young or low-risk individuals with chronic inflammatory diseases, as these are considered risk-enhancing factors.9,15,17–19

The current European Society of Cardiology and European Atherosclerosis Society (ESC/EAS) guidelines recommend CAC score assessment in individuals at low or moderate risk who may benefit from statin therapy. The presence of CAC scores>100 may reclassify these individuals to a higher risk category and help guide decisions on prevention strategies.9 Multiple epidemiological studies have reported on the prevalence of increased CAC score among patients with psoriasis, and a recent meta-analysis concluded that coronary artery disease determined by CAC score is more prevalent in individuals with psoriasis.20

In this work, we evaluate the presence and magnitude of subclinical coronary artery disease determined by CAC score among the different ESC/EAS CV risk categories, as well as the potential for risk reclassification, in patients with severe psoriasis from a low CV risk population.

Materials and methodThis is a unicentric cross-sectional study in 111 patients with severe chronic plaque psoriasis from a low CV risk population in the Mediterranean region. This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board. Adult patients with severe psoriasis and no history of ischemic heart disease were recruited consecutively from the outpatient dermatology clinic at our tertiary care center between February 2019 and February 2021. The diagnosis of severe psoriasis was based on the necessity of systemic therapy and/or a Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI)≥10 and/or body surface involvement≥10%. An informed consent was obtained prior to inclusion in the study.

Epidemiological and clinical data were recovered from the electronic medical records and from the anamnesis and physical examination at the recruitment visit. Data on their lipid profile was obtained from fasting blood samples within 6 months of the recruitment date. Patients were classified into four CV risk categories (low, moderate, high and very-high-risk) according to the HeartScore/SCORE calibrated charts for low-risk regions and the ESC/EAS guideline recommendations on CV risk stratification.9

Patients underwent coronary computed tomography using one of two scanners (Revolution EVO and Discovery CT 750HD, GE Healthcare, Spain) and had CAC scores blindly determined by an experienced cardiologist or radiologist using the commercially available software SmartScore (GE Healthcare), with threshold set at>130 Hounsfield units and expressed in Agatston units and percentile. Patients were then classified into four CAC score categories (0, 1–99, 100–299 and >300 Agatston units).17,21 Presence of subclinical coronary artery disease was defined as a CAC score of >0.22 Patients in the moderate-risk SCORE category with a CAC score of ≥100 were considered to be reclassified as recommended by the 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines.9 Reclassification was also considered for patients in the low-risk category with a CAC score>0, as this would indicate presence of subclinical coronary artery disease.

Data was processed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 25 and portrayed using figures generated with Microsoft Excel version 16.35. Descriptive statistics were performed using the mean and standard deviation to express quantitative variables, and absolute frequencies and percentages to describe qualitative variables. Statistical analysis was performed to evaluate associations between clinical variables and the presence and magnitude of subclinical coronary artery disease in the whole study population and in the non-high-risk categories. For the latter, reclassification was also evaluated in the analysis.

A univariate analysis was performed first including the following variables: age, sex, current smoking status, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, BMI, abdominal obesity, metabolic syndrome, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol levels, LDL and HDL-cholesterol levels, total cholesterol/HDL ratio, duration of psoriasis, highest recorded PASI, concomitant psoriatic arthritis and current biologic therapy. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test and continuous variables were compared using the t-Student test or the U Mann–Whitney test when following a normal or non-normal distribution, respectively. A multivariate analysis with logistic and linear regression models was then performed including main CV risk factors (age, sex, current smoking status, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, systolic blood pressure and total cholesterol levels) and variables with a statistically significant association in the univariate analysis. In all cases, statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

ResultsPatient baseline characteristicsData on the baseline characteristics of the study population is shown in Table 1, including patient demographics, CV risk factors and stratification as well as characteristics of psoriasis. Patients were predominantly male and middle-aged, with a relatively high prevalence of hyperlipidemia, obesity, abdominal obesity and metabolic syndrome. The majority of patients belonged to the non-high-risk categories, with a preponderance of the low-risk category. A history of diabetes mellitus was present in 21.6% of patients, which in all cases conferred a status of either high-risk or very-high risk. Only 5 (4.5%) patients had a high-risk status due to their SCORE risk estimation.

Baseline characteristics of the study population (n=111).

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean±SD | 48.7±13.4 |

| Male,n(%) | 67 (60.4) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean±SD | 29.0±6.5 |

| Underweight, n (%) | 1 (0.9) |

| Normal weight, n (%) | 32 (28.8) |

| Overweight, n (%) | 34 (30.6) |

| Obesity, n (%) | 44 (39.6) |

| Abdominal obesity, n (%) | 54 (48.6) |

| Metabolic syndrome, n (%) | 42 (37.8) |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 35 (31.5) |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 25 (22.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus type 2, n (%) | 24 (21.6) |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 53 (47.7) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg, mean±SD | 128.8±13.6 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL, mean±SD | 202.7±37.4 |

| LDL-cholesterol, mg/dL, mean±SD | 124.4±32.6 |

| HDL-cholesterol, mg/dL, mean±SD | 52.3±19.2 |

| Total cholesterol/HDL-cholesterol ratio, mean±SD | 4.2±1.1 |

| Psoriasis characteristics | |

| Duration of psoriasis, years, mean±SD | 23±11.8 |

| Highest recorded PASI, mean±SD | 16.1±8.4 |

| Concomitant psoriatic arthritis, n (%) | 30 (27) |

| Biologic therapy, n (%) | 105 (96.6) |

| 2019 ESC/EAS CV risk categories | |

| Low-risk, n (%) | 58 (52.3) |

| Moderate-risk, n (%) | 24 (21.6) |

| High-risk, n (%) | 20 (18) |

| Very-high-risk, n (%) | 9 (8.1) |

| Statin therapy,n(%) | 26 (23.4) |

| Low intensity, n (%) | 2 (1.8) |

| Moderate intensity, n (%) | 17 (15.3) |

| High intensity, n (%) | 7 (6.3) |

SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; LDL, low density lipoprotein; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; ESC, European Society of Cardiology; EAS, European Atherosclerosis Society.

Patients generally presented a long duration of psoriasis and almost all cases required biologic therapy, with up to 17.1% of patients requiring intensified dosing regimens due to the severity of their disease. Only 6 (5.4%) patients were treated with classic systemic therapies. Prior statin therapy had been started in 26 (23.4%) patients. Sixteen of these patients belonged to the high- and very-high-risk categories. The remaining 10 patients were in the moderate-risk category, 9 of which received moderate intensity statins and 1 received low intensity statin therapy.

Assessment of coronary artery disease by CAC scoreTable 2 shows the data regarding subclinical coronary artery disease assessment by CAC score. Presence of subclinical coronary artery disease was detected in a total of 46 (41.4%) patients. These accounted for 86.2% of the patients in the high-risk and very-high-risk categories and 25.6% of the patients in non-high-risk categories. Twenty-four (52.2%) of the patients with positive CAC scores were above the >100 threshold proposed by the ESC/EAS guidelines for reclassification. However, the majority (66.7%) of these patients already belonged to the high-risk and very-high-risk categories. Only 6 (25%) and 2 (8.3%) of these patients belonged to the moderate-risk and low-risk categories, respectively.

Assessment of subclinical coronary artery disease by CAC score determined by computed tomography (n=111).

| Variable | Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Presence of subclinical coronary artery diseasea, n (%) | 46 (41.4) | |

| Low-risk category, n (%) | 8 (13.8) | <0.001 |

| Moderate-risk category, n (%) | 13 (54.2) | |

| High-risk category, n (%) | 18 (90) | |

| Very-high-risk category, n (%) | 7 (77.8) | |

| CAC score, Agatston units, mean±SD | 159±447 | |

| Low-risk category, mean±SD | 10±43 | <0.001 |

| Moderate-risk category, mean±SD | 185±341 | |

| High-risk category, mean±SD | 259±350 | |

| Very-high-risk category, mean±SD | 824±1195 | |

| Categories by CAC score | ||

| CAC score 0, n (%) | 65 (58.6) | – |

| CAC score 1–99, n (%) | 22 (19.8) | |

| CAC score 100–299, n (%) | 9 (8.1) | |

| CAC score>300, n (%) | 15 (13.5) | |

CAC, coronary artery calcium; SD, standard deviation.

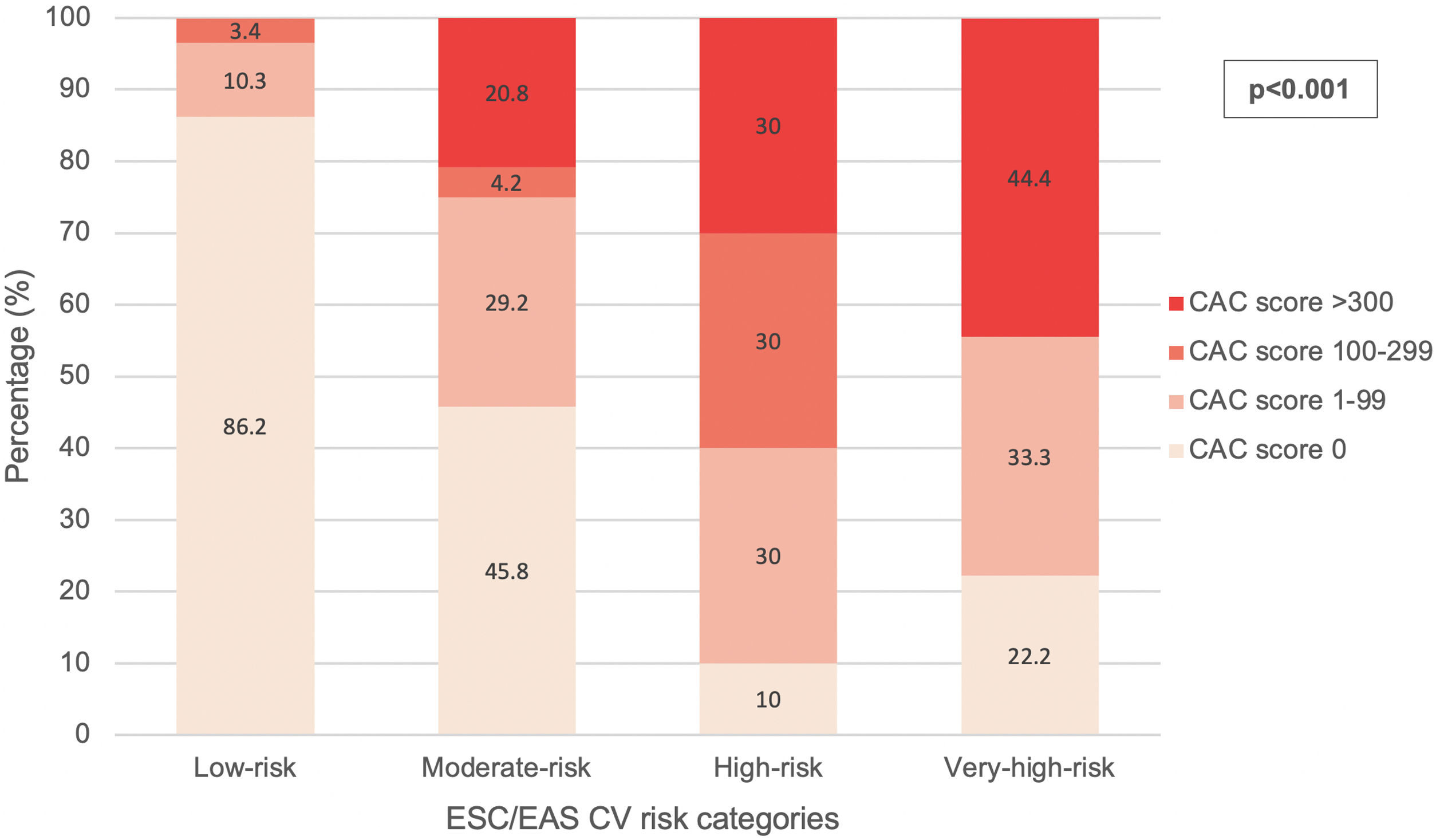

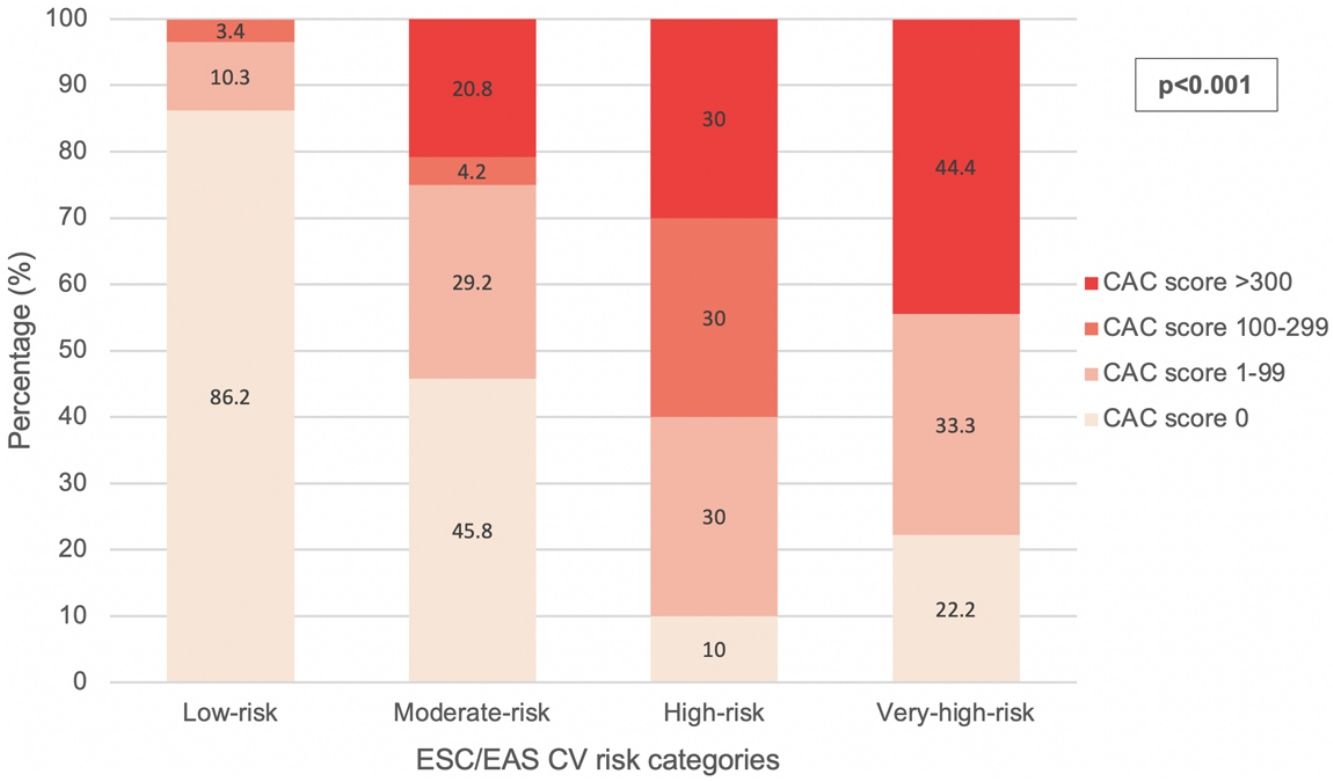

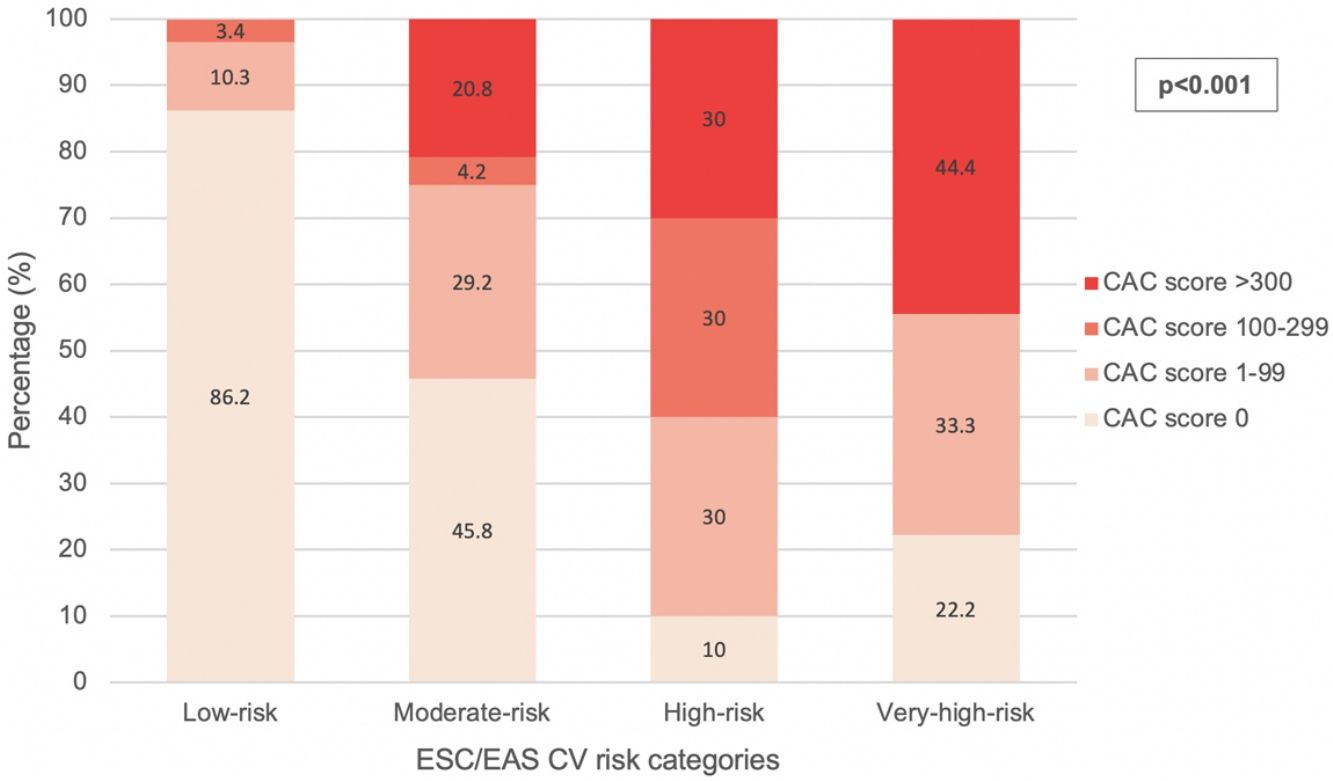

According to the exposed criteria for CV risk reclassification, 14 (17.1%) of the patients in non-high-risk categories were considered to be reclassifiable due to their CAC score. This percentage was higher (25%) when considering the moderate-risk category alone and lower (13.8%) in the low-risk category. The distribution of CAC scores among each CV risk category is illustrated in Fig. 1. In the low-risk category, 1 (1.7%) patient had a CAC score 1–99 below the 75th percentile and 5 (8.6%) above the 75th percentile. In the moderate-risk category, 5 (20.8%) patients had a CAC score 1–99 below the 75th percentile and 2 (8.3%) above the 75th percentile. None of the patients in the low-risk category presented CAC scores of >300 and none of the patients in the very-high-risk category had CAC scores within the 100–299 interval.

Statistical analysisAs shown in Table 2 and Fig. 1, the presence of subclinical coronary artery disease, the mean CAC score and the distribution of CAC score intervals correlated with the ESC/EAS CV risk categories.

The univariate analysis for the whole study population revealed a significant association between the presence of subclinical coronary artery disease and a history of either hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, current biologic therapy, older age (mean 57.4 years vs. 42.6 years) and higher levels of systolic blood pressure (mean 133mmHg vs. 125.8mmHg). After the multivariate analysis, only older age was associated with subclinical coronary artery disease (OR 1.1; 95% CI, 1.04–1.6; p=0.001). In the univariate analysis, the magnitude of subclinical coronary artery disease in terms of CAC score correlated positively with older age, hyperlipidemia and diabetes, but only the former was associated with higher CAC scores in the multivariate analysis (standardized beta coefficient, 0.288; t, 2.722; p=0.008).

Regarding patients in the non-high-risk categories alone, the univariate analysis revealed that subclinical coronary artery disease was associated with older age (mean 54.9 years vs. 41.7 years), hypertension and hyperlipidemia. In the multivariate analysis, only age was significantly associated with subclinical coronary artery disease among non-high-risk populations (OR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.04–1.2; p=0.002). With respect to CAC scores, in both the univariate and multivariate analysis age (standardized beta coefficient, 0.316; t, 2.595; p=0.011) and hyperlipidemia (standardized beta coefficient, 0.397; t, 3.195; p=0.002). were associated with the magnitude of subclinical coronary artery disease. Reclassification was only associated with older age (mean 51.6 years vs. 43.8 years) in the univariate and the multivariate analysis (OR 1.07; 95% CI, 1.01–1.14; p=0.047).

DiscussionThe scientific community is constantly making efforts to reduce the burden of cardiovascular disease worldwide, as it remains the leading cause of death globally and among middle and high-income countries. Primary prevention strategies are essential for this matter, but they are most efficient when adjusted to each individual's risk. This has created a necessity to improve on CV risk assessment and, as a result, the relevance of CV imaging techniques has grown. Dermatologists have become increasingly involved in the recognition and management of comorbidities in patients with psoriasis, such as the increased CV risk. It is important for dermatologists to be aware of recent developments in CV risk assessment as it is challenging to adequately establish the CV risk of patients with psoriasis using clinical scores. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies reporting on the utility of CAC in patients with psoriasis regarding the detection and magnitude of subclinical coronary artery disease in each ESC/EAS CV risk category, which could reflect on the potential for risk reclassification in this population.

The prevalence of subclinical coronary artery disease detected by CAC in our study was 41.4%, in line with that previously described by studies with large samples of psoriasis patients. Santilli et al and Mansouri et al found a prevalence of 44.4% (n=207) and 41.9% (n=129), respectively. Their samples had comparable epidemiologic characteristics and prevalence of main CV risk factors, except for a high prevalence of dyslipidemia (82.9%) in the latter.8,25 A slightly lower prevalence of coronary artery disease by CAC has been reported by other studies. Yiu et al. and Hujler et al. reported prevalence of 28.5% (n=70) and 29.8% (n=57). While the latter described patients with similar characteristics to ours, the former did report a lower prevalence of diabetes mellitus (8%), hypertension (15%) and hypercholesterolemia (12%).26,27 Despite these differences, all these studies coincide in what was concluded by a recent meta-analysis: the prevalence of coronary artery disease in psoriasis patients is higher than in healthy controls.20

The multivariate analysis in our study revealed that only age was associated with the presence and magnitude of subclinical coronary artery disease in the population as a whole. Santilli et al also found a clear increase in atherosclerosis prevalence by age.8 This is expected given that age is a main CV risk factor. On the contrary to what Mansouri et al reported, we did not find a significant association with other known CV risk factors such as male sex, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, metabolic syndrome, BMI, SBP or HDL-cholesterol.25 Although not in our study, previous works have described an association between psoriasis severity and both presence and magnitude of coronary artery disease.27,28

Multiple studies have demonstrated that CAC is a powerful reclassification tool that can improve CV risk assessment beyond clinical scores.12–14 Reclassification itself is a valuable outcome as it may improve primary prevention strategies, not only through the decision of initiating or modifying statin therapy, but also through the better adjustment of treatment goals to the resulting CV risk category.9 Furthermore, patient visualization of their own CAC score has been demonstrated to induce beneficial behavioral modifications resulting in weight loss and increased adherence to statin therapy, which can further improve the effectiveness of primary prevention measures.23,24

Our results indicate that when performed in psoriasis patients from a low CV risk region, CAC testing may reclassify up to 17.1% of individuals in the low and moderate ESC/EAS CV risk categories, and up to 25% of individuals in the moderate-risk category alone. In this study, the presence and magnitude of subclinical coronary artery disease and the distribution of CAC score intervals did correlate with the ESC/EAS CV risk categories. However, it is worth noting that up to 13.8% of patients classified as low-risk actually did have subclinical coronary artery disease by CAC score. These results suggest that although HeartScore/SCORE charts and ESC/EAS CV risk categories are powerful clinical tools that adequately discriminate CV risk, they may underestimate the risk of individuals with psoriasis.5,6 As a result, a considerable proportion of patients in non-high-risk categories would fail to adequately benefit from the primary prevention strategies at our disposal.

A recent study performed by Gonzalez-Cantero et al. also addressed CV risk reclassification using imaging techniques in patients with psoriasis in non-high-risk categories.29 In this study, CV risk assessment was performed with different imaging techniques (coronary computed tomography angiography in an American cohort, n=165; femoral and carotid ultrasound in a European cohort, n=73) and reclassification was based on the presence of atherosclerosis. No threshold was involved such as the CAC>100 used in our study as recommended by the ESC/EAS guidelines for reclassification in the moderate-risk category. Though they reported higher reclassification rates, the differences in methodology do not allow for adequate comparison. Nevertheless, their results also support the idea that clinical CV risk classification based on traditional risk factors is suboptimal and can underestimate risk in patients with psoriasis, a population that could benefit from image-guided CV risk stratification.

In addition to its reclassification ability, CAC has several advantages that make it convenient for screening purposes in asymptomatic individuals, including low radiation exposure, wide availability, low cost and not requiring intravenous contrast.15 However, it is unclear if the ESC/EAS recommendations on using CAC for CV risk assessment would translate to a systematic use in our outpatient clinics attending patients with severe psoriasis. In this study, we attempted to identify clinical variables that could indicate which of our patients in non-high-risk categories could benefit from CAC testing for CV risk reclassification. Although both older age and hyperlipidemia were associated with increased severity of subclinical coronary artery disease, multivariate analysis revealed that only age predicted its presence and risk reclassification. We did not identify other variables that could help guide the decision to perform CAC testing.

The main benefit of CAC according to practice guidelines is to help establish the indication and intensity of statin therapy as a primary prevention measure in patients at low and moderate CV risk. However, this clinical outcome was not be evaluated in our study. Nevertheless, several consensus documents include recommendations on statin therapy based on absolute CAC score and percentile.17–19 According to these guidelines, 1.7% of our patients in the low-risk category should consider initiating a moderate intensity statin and up to 12.1% could be recommended moderate-high intensity statin therapy. In the moderate-risk category, 20.8% of our patients should consider initiating a moderate intensity statin, 12.5% would be recommended moderate-high intensity statin therapy and 20.8% would be recommended starting on a high intensity statin. Although 10 patients were already on low or moderate intensity statins, 4 of them might benefit from switching to a high intensity statin given their CAC score>300. Nevertheless, the decision of initiating or modifying statin therapy requires an individualized assessment and should follow an informed patient-physician discussion.9,17,18

Limitations regarding study design include its cross-sectional nature, the limited sample size per CV risk category, the absence of a control group and the inclusion of treated patients. Other limitations result from disadvantages inherent to CAC as an imaging technique: it fails to detect non-calcified plaques and CAC scores may increase with statin therapy.9,15 Since a higher prevalence of coronary artery disease in patients with psoriasis has been demonstrated in multiple studies, performing CAC testing in healthy controls was beyond the scope of this work. All of our patients received systemic treatment, and almost all received biologic therapy, which could result in underestimation of coronary artery disease as biologic therapy may reduce progression of CAC.30 Furthermore, inclusion of treated patients with different degree of disease control could have affected our ability to identify a relationship between psoriasis severity and coronary artery disease. Highest recorded PASI was used as a severity indicator in an attempt to alleviate this, although some patients lack untreated PASI as they were already receiving systemic therapy when first attended at our clinic.

In conclusion, over 40% of patients with severe psoriasis from a low-risk region and up to 25% of those in non-high-risk categories have subclinical coronary artery disease. These findings highlight the difficulty of adequately assessing the CV risk of patients with psoriasis using clinical scores. CAC is useful for reclassification purposes in CV risk assessment of patients with severe psoriasis, even in young patients from low-risk categories. Up to 17% of patients might be reclassified after CAC testing. Perhaps the same age range (40–70 years) recommended for clinical CV assessment could be used to guide CAC testing. However, further research is required to establish how CAC could be implemented in everyday practice dedicated to severe psoriasis.

Funding statementThis work has received funding from Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc. The funder has not been involved in data collection and analysis or manuscript preparation.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.